Writing Assignments

Lyle Cleeland and Lisa Moody

Introduction

Assignments are a common method of assessment at university and require careful planning and good quality research. Developing critical thinking and writing skills are also necessary to demonstrate your ability to understand and apply information about your topic. It is not uncommon to be unsure about the processes of writing assignments at university.

This chapter has a collection of resources that will provide you with the skills and strategies to understand assignment requirements and effectively plan, research, write, and edit your assignments.

Task Analysis and Deconstructing an Assignment

It is important that you spend sufficient time understanding all the requirements before you begin researching and writing your assignments.

The assessment task description (located in your subject outline) provides key information about an assessment item, including the question. It is essential to scan this document for topic, task, and limiting words. If there are any elements you do not understand, you should clarify these as early as possible.

| Topic words | These are words and concepts you have to research. |

| Task words | These will tell you how to approach the assignment and structure the information you find in your research (e.g. discuss, analyse). |

| Limiting words | These words define the scope or parameters of the assignment, e.g., Australian perspectives, a particular jurisdiction (this would be relevant then to which laws, codes or standards you consulted) or a timeframe. |

Make sure you have a clear understanding of what the task word requires you to address.

| Task word | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Account for | Give reasons for or explain why something has occurred. This task directs you to consider contributing factors to a certain situation or event. You are expected to make a decision about why these occurred, not just describe the events. | Account for the factors that led to the global financial crisis. |

| Analyse | Consider the different elements of a concept, statement or situation. Show the different components and show how they connect or relate. Your structure and argument should be logical and methodical. | Analyse the political, social and economic impacts of climate change. |

| Assess | Make a judgement on a topic or idea. Consider its reliability, truth and usefulness. In your judgement, consider both the strengths and weaknesses of the opposing arguments to determine your topic’s worth (similar to evaluate). | Assess the efficacy of cogitative behavioural therapy (CBT) for the treatment of depression. |

| Classify | Divide your topic into categories or sub-topics logically (could possibly be part of a more complex task). | Classify the artists studied this semester according to the artistic periods they best represent. Then choose one artist and evaluate their impact on future artists. |

| Comment on | State your opinion on an issue or idea. You may explain the issue or idea in more detail. Be objective and support your opinion with reliable evidence. | Comment on the government’s proposal to legalise safe injecting rooms. |

| Compare OR Compare and contrast | Show the similarities and differences between two or more ideas, theories, systems, arguments, or events. You are expected to provide a balanced response, highlighting similarities and differences. | Compare the efficiency of wind and solar power generation for a construction site. |

| Contrast | Point out only the differences between two or more ideas, theories, systems, arguments, or events. | Contrast virtue ethics and utilitarianism as models for ethical decision making. |

| Critically (this is often used with another task word, e.g. critically evaluate, critically analyse, critically discuss) | It does not mean to criticise; instead, you are required to give a balanced account, highlighting strengths and weaknesses about the topic. Your overall judgment must be supported by reliable evidence and your interpretation of that evidence. | Critically analyse the impacts of mental health on recidivism within youth justice. |

| Define | Provide a precise meaning of a concept. You may need to include the limits or scope of the concept within a given context. | Define digital disruption as it relates to productivity. |

| Describe | Provide a thorough description, emphasising the most important points. Use words to show appearance, function, process, events or systems. You are not required to make judgements. | Describe the pathophysiology of Asthma. |

| Distinguish | Highlight the differences between two (possibly confusing) items. | Distinguish between exothermic and endothermic reactions. |

| Discuss | Provide an analysis of a topic. Use evidence to support your argument. Be logical and include different perspectives on the topic (This requires more than a description). | Discuss how Brofenbrenner’s ecological systems theory applies to adolescence. |

| Evaluate | Review both positive and negative aspects of a topic. You may need to provide an overall judgement regarding the value or usefulness of the topic. Evidence (referencing) must be included to support your writing. | Evaluate the impact of inclusive early childhood education programs on subsequent high school completion rates for First Nations students. |

| Explain | Describe and clarify the situation or topic. Depending on your discipline area and topic, this may include processes, pathways, cause and effect, impact, or outcomes. | Explain the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the film industry in Australia. |

| Illustrate | Clarify a point or argument with examples and evidence. | Illustrate how society’s attitudes to disability have changed from a medical model to a holistic model of disability. |

| Justify | Give evidence which supports an argument or idea; show why a decision or conclusions were made. Justify may be used with other topic words, such as outline, argue. | Write a report outlining the key issues and implications of a welfare cashless debit card trial and make three recommendations for future improvements. Justify your decision-making process for the recommendations. |

| Review | A comprehensive description of the situation or topic which provides a critical analysis of the key issues. | Provide a review of Australia’s asylum policies since the Pacific Solution in 2001. |

| Summarise | An overview or brief description of a topic. (This is likely to be part of a larger assessment task.) | Summarise the process for calculating the correct load for a plane. |

The marking criteria or rubric, is an important document to look at before you begin your assignment. This outlines how your assignment will be marked and should be used as a checklist to make sure you have included all the information required.

The assessment task description will also include the following:

- Due date

- Word limit (or word count)

- Referencing style and research expectations

- Formatting requirements

For a more detailed discussion on task analysis, criteria sheets, and marking rubrics, visit the chapter Managing Assessments.

Preparing your ideas

Brainstorm or concept map: List possible ideas to address each part of the assignment task based on what you already know about the topic from lectures and weekly readings.

Finding appropriate information: Learn how to find scholarly information for your assignments which is:

- accurate

- recent

- reliable

See the chapter Working With Information for a more detailed explanation.

What is Academic Writing?

Academic writing tone and style

Many of the assessment items you prepare will require an academic writing style. Sometimes this feels awkward when you begin. However, it is good to know that practice at academic writing reduces this feeling.

| Academic writing | Non-academic writing |

| Is clear, concise and well-structured. | Is verbose and may use more words than are needed. |

| Is formal. It writes numbers under ten in full. | Writes numbers under ten as numerals and uses symbols such as “&” instead of writing it in full. |

| Is reasoned and supported (logically developed). | Uses humour – puns, sarcasm. |

| Is authoritative (writes in third person- “Evidence suggests that…”). | Writes in first person “I think”, “I found”. |

| Utilises the language of the field/industry/subject. | Uses colloquial language, e.g., “mate”. |

Thesis statements

One of the most important steps in writing an essay is constructing your working thesis statement. A thesis statement tells the reader the purpose, argument, or direction you will take to answer your assignment question. It is found in the introduction paragraph. The thesis statement:

- Directly relates to the task. Your thesis statement may even contain some of the keywords or synonyms from the task description.

- Does more than restate the question.

- Is specific and uses precise language.

- Lets your reader know your position or the main argument that you will support with evidence throughout your assignment.

- Usually has two parts: subject and premise.

- The subject is the key content area you will be covering.

- The premise is the key argument or position.

A key element of your thesis statement should be included in the topic sentence of each paragraph.

Planning your assignment structure

When planning and drafting assignments, it is important to consider the structure of your writing. Academic writing should have a clear and logical structure and incorporate academic research to support your ideas. It can be hard to get started and at first you may feel nervous about the size of the task. This is normal. If you break your assignment into smaller pieces, it will seem more manageable as you can approach the task in sections. Refer to your brainstorm or plan. These ideas should guide your research and will also inform what you write in your draft. It is sometimes easier to draft your assignment using the 2-3-1 approach, that is, write the body paragraphs first followed by the conclusion and finally the introduction.

No one’s writing is the best quality on the first few drafts, not even professional writers. It is strongly advised that you accept that your first few drafts will feel rough. Ultimately, it is the editing and review processes which lead to good quality ideas and writing.

Writing introductions and conclusions

Clear and purposeful introductions and conclusions in assignments are fundamental to effective academic writing. Your introduction should tell the reader what is going to be covered and how you intend to approach this. Your conclusion should summarise your argument or discussion and signal to the reader that you have come to a conclusion with a final statement.

Writing introductions

An effective introduction needs to inform your reader by establishing what the paper is about and provide four basic elements:

- A brief background or overview of your assignment topic and key information that reader needs to understand your thesis statement.

- Scope of discussion (key points discussed in body paragraphs).

- A thesis statement (see section above).

The below example demonstrates the different elements of an introductory paragraph.

1) Information technology is having significant effects on the communication of individuals and organisations in different professions. 2) Digital technology is now widely utilised in health settings, by health professionals. Within the public health field, doctors and nurses need to engage with ongoing professional development relating to digital technology in order to ensure efficient delivery of services to patients and communities. 3) Clearly, information technology has significant potential to improve health care and medical education, but some health professionals are reluctant to use it.

1 Brief background/overview | 2 Scope of what will be covered | 3 The thesis statement

Writing conclusions

You should aim to end your assignments with a strong conclusion. Your conclusion should restate your thesis statement and summarise the key points you have used to prove this thesis. Finish with a key point as a final impactful statement. If your assessment task asks you to make recommendations, you may need to allocate more words to the conclusion or add a separate recommendations section before the conclusion. Use the checklist below to check your conclusion is doing the right job.

Conclusion checklist

- Have you referred to the assignment question and restated your argument (or thesis statement), as outlined in the introduction?

- Have you pulled together all the threads of your essay into a logical ending and given it a sense of unity?

- Have you presented implications or recommendations in your conclusion? (if required by your task).

- Have you added to the overall quality and impact of your essay? This is your final statement about this topic; thus, a key take-away point can make a great impact on the reader.

- Do not add any new material or direct quotes in your conclusion.

This below example demonstrates the different elements of a concluding paragraph.

1) Clearly, communication of individuals and organisations is substantially influenced or affected by information technology across professions. 2) Managers must ensure that effective in-house training programs are provided for public health professionals, so that they become more familiar with the particular digital technologies 3) In addition, the patients and communities being served by public health professionals benefit when communication technologies are effectively implemented. 4) The Australian health system may never be completely free of communication problems, however, ensuring appropriate and timely professional development, provision of resource sand infrastructure will enhance service provision and health outcomes.

1 Reference to thesis statement – In this essay the writer has taken the position that training is required for both employees and employers. | 2-3 Structure overview – Here the writer pulls together the main ideas in the essay. | 4 Final summary statement that is based on the evidence.

Note: The examples in this document are adapted from the University of Canberra and used under a CC-BY-SA-3.0 licence.

Writing paragraphs

Each paragraph should have its own clearly identified Topic Sentence or main idea which relates to the argument or point (thesis) you are developing. This idea should then be explained by additional sentences which you have paraphrased from good quality sources and referenced according to the recommended guidelines of your subject (see the chapter Working with Information). Paragraphs are characterised by moving from general information to the specific details. A common structure for paragraphs in academic writing is as follows.

Topic Sentence

The first sentence of the paragraph is the Topic Sentence. This is the main idea of the paragraph and tells the reader what you will discuss in more detail below. Each Topic Sentence should address one aspect of your overall argument.

Supporting Sentences

Supporting Sentences provide more explanation, evidence, data, analogies, and/or analysis of the main idea.

Linking/Concluding Sentence

Some paragraphs are best linked to the following paragraph through a Linking/Concluding Sentence. Not every paragraph lends itself to this type of sentence.

Use the checklist below to check your paragraphs are clear and well formed.

Paragraph checklist

- Does your paragraph have a clear main idea?

- Is everything in the paragraph related to this main idea?

- Is the main idea adequately developed and explained?

- Have you included evidence to support your ideas?

- Have you concluded the paragraph by connecting it to your overall topic (where appropriate)?

Writing sentences

Make sure all the sentences in your paragraphs make sense. Each sentence must contain a verb to be a complete sentence. Avoid incomplete sentences or ideas that are unfinished and create confusion for your reader. Also avoid overly long sentences, which happens when you join two ideas or clauses without using the appropriate punctuation. Address only one key idea per sentence. See the chapter English Language Foundations for examples and further explanation.

Use transitions (linking words and phrases) to connect your ideas between paragraphs and make your writing flow. The order that you structure the ideas in your assignment should reflect the structure you have outlined in your introduction. Refer to the transition words table in the chapter English Language Foundations.

Paraphrasing and Synthesising

What is paraphrasing?

Paraphrasing is changing the writing of another author into your words while retaining the original meaning. You must acknowledge the original author as the source of the information in your citation. Follow the steps in this table to help you build your skills in paraphrasing. Note: paraphrasing generally means that the rewritten section is the same or a similar length to the original.

| 1. | Make sure you understand what you are reading. Look up keywords to understand their meanings. |

| 2. | Record the details of the source so you will be able to cite it correctly in text and in your reference list. |

| 3. | Identify words that you can change to synonyms (but do not change the key/topic words). |

| 4. | Change the type of word in a sentence (for example change a noun to a verb or vice versa). |

| 5. | Eliminate unnecessary words or phrases from the original that you don’t need in your paraphrase. |

| 6. | Change the sentence structure (for example, change a long sentence to several shorter ones or combine shorter sentences to form a longer sentence). |

Example of paraphrasing

Please note that these examples and in-text citations are for instructional purposes only.

Original text

Health care professionals assist people, often when they are at their most vulnerable. To provide the best care and understand their needs, workers must demonstrate good communication skills. They must develop patient trust and provide empathy to effectively work with patients who are experiencing a variety of situations including those who may be suffering from trauma or violence, physical or mental illness or substance abuse (French & Saunders, 2018).

Poor quality paraphrase example

This is a poor example of paraphrasing. Some synonyms have been used and the order of a few words changed within the sentences. However, the colours of the sentences indicate that the paragraph follows the same structure as the original text.

Health care sector workers are often responsible for vulnerable patients. To understand patients and deliver good service, they need to be excellent communicators. They must establish patient rapport and show empathy if they are to successfully care for patients from a variety of backgrounds and with different medical, psychological and social needs (French & Saunders, 2018).

A good quality paraphrase example

This example demonstrates a better quality paraphrase. The author has demonstrated more understanding of the overall concept in the text by using the keywords as the basis to reconstruct the paragraph.

Empathetic communication is a vital skill for health care workers. Professionals in these fields are often responsible for patients with complex medical, psychological and social needs. Empathetic communication assists in building rapport and gaining the necessary trust to assist these vulnerable patients by providing appropriate supportive care (French & Saunders, 2018).

The good quality paraphrase example demonstrates understanding of the overall concept in the text by using key words as the basis to reconstruct the paragraph. Note how the blocks of colour have been broken up to see how much the structure has changed from the original text.

What is synthesising?

Synthesising means to bring together more than one source of information to strengthen your argument. Once you have learnt how to paraphrase the ideas of one source at a time, you can consider adding additional sources to support your argument. Synthesis demonstrates your understanding and ability to show connections between multiple pieces of evidence to support your ideas and is a more advanced academic thinking and writing skill.

Follow the steps in this table to improve your synthesis techniques.

| 1. | Check your referencing guide to learn how to correctly reference more than one author at a time in your paper. |

| 2. | While taking notes for your research, try organising your notes into themes. This way you can keep similar ideas from different authors together. |

| 3. | Identify similar language and tone used by authors so that you can group similar ideas together. |

| 4. | Synthesis can not only be about grouping ideas together that are similar, but also those that are different. See how you can contrast authors in your writing to also strengthen your argument. |

Example of synthesis

There is a relationship between academic procrastination and mental health outcomes. Procrastination has been found to have a negative effect on students’ well-being (Balkis, & Duru, 2016). Yerdelen et al.’s (2016) research results suggest that there is a positive association between procrastination and anxiety. This is corroborated by Custer’s (2018) findings which indicate that students with higher levels of procrastination also report greater levels of anxiety. Therefore, it could be argued that procrastination is an ineffective learning strategy that leads to increased levels of distress.

Topic sentence | Statements using paraphrased evidence | Critical thinking (student voice) | Concluding statement – linking to topic sentence

This example demonstrates a simple synthesis. The author has developed a paragraph with one central theme and included explanatory sentences complete with in-text citations from multiple sources. Note how the blocks of colour have been used to illustrate the paragraph structure and synthesis (i.e. statements using paraphrased evidence from several sources). A more complex synthesis may include more than one citation per sentence.

Paraphrasing and synthesising are powerful tools that you can use to support the main idea of a paragraph. It is likely that you will regularly use these skills at university to incorporate evidence into explanatory sentences and strengthen your essay. It is important to paraphrase and synthesise because:

- Paraphrasing is regarded more highly at university than direct quoting.

- Paraphrasing can also help you better understand the material.

- Paraphrasing and synthesising demonstrate that you have understood what you have read through your ability to summarise and combine arguments from the literature using your own words.

Creating an Argument

What does this mean?

In academic writing, if you are asked to create an argument, this means you are asked to have a position on a particular topic, and then justify your position using evidence from valid scholarly sources.

What skills do you need to create an argument?

In order to create a good and effective argument, you need to be able to:

- Read critically to find evidence.

- Plan your argument.

- Think and write critically throughout your paper to enhance your argument.

For tips on how to read and write critically, refer to the chapter Thinking for more information. A formula for developing a strong argument is presented below.

A formula for a good argument

What does an argument look like?

As can be seen from the figure above, including evidence is a key element of a good argument. While this may seem like a straightforward task, it can be difficult to think of wording to express your argument. The table below provides examples of how you can illustrate your argument in academic writing.

| Introducing your argument | • This paper will argue/claim that… • …is an important factor/concept/idea/ to consider because… • … will be argued/outlined in this paper. |

| Introducing evidence for your argument | • Smith (2014) outlines that…. • This evidence demonstrates that… • According to Smith (2014)… • For example, evidence/research provided by Smith (2014) indicates that… |

| Giving the reason why your point/evidence is important | • Therefore this indicates… • This evidence clearly demonstrates…. • This is important/significant because… • This data highlights… |

| Concluding a point | • Overall, it is clear that… • Therefore, … are reasons which should be considered because… • Consequently, this leads to…. • The research presented therefore indicates… |

Editing and proofreading (reviewing)

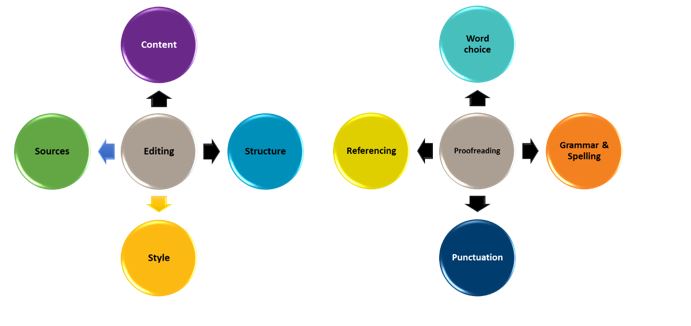

Once you have finished writing your first draft it is recommended that you spend time revising your work. Proofreading and editing are two different stages of the revision process.

- Editing considers the overall focus or bigger picture of the assignment.

- Proofreading considers the finer details.

As can be seen in the figure above, there are four main areas that you should review during the editing phase of the revision process. The main things to consider when editing include content, structure, style, and sources. It is important to check that all the content relates to the assignment task, the structure is appropriate for the purposes of the assignment, the writing is academic in style, and that sources have been adequately acknowledged. Use the checklist below when editing your work.

Editing checklist

- Have I answered the question accurately?

- Do I have enough credible, scholarly supporting evidence?

- Is my writing tone objective and formal enough or have I used emotive and informal language?

- Have I written in third person, not first person?

- Do I have appropriate in-text citations for all my information?

- Have I included the full details for all my in-text citations in my reference list?

During proofreading, it is important to check your work for word choice, grammar and spelling, punctuation, and referencing errors. It can be easy to mis-type words like ‘from’ and ‘form’ or mix up words like ‘trail’ and ‘trial’ when writing about research, apply American rather than Australian spelling, include unnecessary commas, or incorrectly format your references list. The checklist below is a useful guide that you can use when proofreading your work.

Proofreading checklist

- Is my spelling and grammar accurate?

- Are my sentences sensible?

- Are they complete?

- Do they all make sense?

- Do the different elements (subject, verb, nouns, pronouns) within my sentences agree?

- Are my sentences too long and complicated?

- Do they contain only one idea per sentence?

- Is my writing concise? Take out words that do not add meaning to your sentences.

- Have I used appropriate discipline specific language but avoided words I don’t know or understand that could possibly be out of context?

- Have I avoided discriminatory language and colloquial expressions (slang)?

- Is my referencing formatted correctly according to my assignment guidelines? (For more information on referencing, refer to the Managing Assessment feedback section).

Conclusion

This chapter has examined the experience of writing assignments. It began by focusing on how to read and break down an assignment question, then highlighted the key components of essays. Next, it examined some techniques for paraphrasing and summarising, and how to build an argument. It concluded with a discussion on planning and structuring your assignment and giving it that essential polish with editing and proofreading. Combining these skills and practising them can greatly improve your success with this very common form of assessment.

Key points

- Academic writing requires clear and logical structure, critical thinking and the use of credible scholarly sources.

- A thesis statement is important as it tells the reader the position or argument you have adopted in your assignment.

- Spending time analysing your task and planning your structure before you start to write your assignment is time well spent.

- Information you use in your assignment should come from credible scholarly sources such as textbooks and peer reviewed journals. This information needs to be paraphrased and referenced appropriately.

- Paraphrasing means putting something into your own words and synthesising means to bring together several ideas from sources.

- Creating an argument is a four step process and can be applied to all types of academic writing.

- Editing and proofreading are two separate processes.

References

Balkis, M., & Duru, E. (2016). Procrastination, self-regulation failure, academic life satisfaction, and affective well-being: underregulation or misregulation form. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 31(3), 439-459.

Custer, N. (2018). Test anxiety and academic procrastination among prelicensure nursing students. Nursing Education Perspectives, 39(3), 162-163.

Yerdelen, S., McCaffrey, A., & Klassen, R. M. (2016). Longitudinal examination of procrastination and anxiety, and their relation to self-efficacy for self-regulated learning: Latent growth curve modeling. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 16(1), 5-22.