Research Philosophy and Theory Development

Learning Objectives

In this chapter you will understand:

- what is meant by research philosophy and paradigms

- what is meant by ontology, empistomology, and axiology

- the differences between deduction, induction, and abduction in relation to theory development.

6.1 Introduction to Research Philosophy and Paradigms

The way in which we conduct research is influenced by what scholars call ‘our worldview’. That is our approach to the conduct of research is informed by the collection of factors about our being, such as our values, attitudes, perceptions, expectations, and backgrounds. Our view of the world is at the heart of our being and influences our minds and behaviours. Hence, our worldview is how we acquire and advance knowledge and it informs our approach to the conduct of research.

Table 6.1. Research paradigms, ontologies, epistemology, and axiology

| Paradigm | Ontology | Epistemology | Axiology |

| Positivism | Realist:

|

Objective:

|

Value-free:

|

| Post-positivism | Critical-realist:

|

Critical and fallible:

|

Value-aware:

|

| Interpretivism | Individual-realist:

|

Interpretive:

|

Value-laden:

|

| Pragmatism | Dynamic:

|

Practical:

|

Value-driven:

|

| Critical realism | Stratified-realist:

|

Explanatory:

|

Value-laden:

|

Paradigms

Scholars talk of worldviews in terms of paradigms or philosophical assumptions that help us to understand the nature of the world and how (i.e. the methods by which) we can understand it (Crotty, 1998; Lincoln & Guba, 2007). These paradigms are the lenses through which researchers view the world and hence, the ways by which researchers design research projects, engage with methodologies and make decisions about the methods to be used and how the data will be collected, analysed, interpreted and presented.

In his 1962 book (Structure of Scientific Revolutions), Thomas Kuhn introduced the term paradigms to describe the “dominant theories or models by which science proceeded, until they were overtaken and superseded by newer and more encompassing theories or models” (Lincoln & Guba, 2007, p. 1). Equally, it is recognised that Rohmann (1999, p. 295) later defined paradigms as “An ideal or archetypal pattern or example that provides a model to be emulated”. Then there are some scholars who use the term paradigms to describe a set of methodologies or methods (e.g., Tashakkori & Teddlie, 2003). Paradigms relevant to research are positivism, post-positivism, interpretivism, pragmatism, and critical realism (Table 6.1).

As the notion of ‘paradigms’ continues to be a much-contested domain in qualitative research, the preferred definition here is aligned with that of Lincoln and Guba (1985, p. 15) who built on the work of Reese (1980) and noted as “a set of basic or metaphysical beliefs … sometimes constituted into a system of ideas that ‘either give us some judgment about the nature of reality, or a reason why we must be content with knowing something less than the nature of reality, along with a method for taking hold of whatever can be known’ (Reese, 1980, p. 352)”. This definition captures the notion that paradigms “an entire set of ideas based on sets of fundamental or metaphysical beliefs” (Lincoln & Guba, 2007, p. 1), which is an important consideration because it behooves researchers to think about how they view the nature of reality (ontology) and the ways by which they come to know about the nature of reality (epistemology). The latter encompasses the theories, models and methods of how researchers come to know about reality or the world they live in (Table 6.1).

Ontology

As stated above, ontology is about how we perceive reality, how we view the nature of reality (Table 6.1), and how we consider the way in which humans engage with reality (Creswell, 2013; Creswell et al., 2007). Ordinarily, our individual research focuses on a phenomenon. Our ontologies allow us to perceive that phenomenon through our own worldviews (i.e., our values, our beliefs, our cultural and sociological backgrounds, our personalities, our attitudes, and so on). Through our ontological lens, we perceive and come to understand the characteristics and nature of that phenomenon and how humans engage with or interact with that phenomenon (e.g., urban greenspaces) or how the phenomenon influences or impacts humans (e.g., climate change). Hence, our ontologies encompass the assumptions that we as researchers make as we explore the phenomenon and endeavour to make sense of it.

Being aware of our ontologies is important in realising that the underlying assumptions of our worldview can assist us in thinking about our research and the phenomenon that we are exploring. That awareness can even lead us to realise some of the limitations in the approach we take with our research. Either way, an awareness of our ontologies lends insight into what we understand as being real in the world and how we conceptualise the phenomenon we are exploring. The main ontological taxonomies are positivism, post-positivism, interpretivism, pragmatism and critical theory (Crotty, 1998; Lincoln & Guba, 2007).

As an example of an ontological stance, a scholar of Management with a social constructivist ontological stance may assume that the various aspects of running a business (e.g., the business model, the recruitment and training of staff, the leadership of the organisation, or customer service) are phenomena that are socially constructed and shaped by the cultural and social factors within which the business is run (e.g., the region or country, the political regime) or even by the individual business owner’s cultural and social identity and background.

Epistemologies

Aligned with one’s ontology is one’s epistemology. I.e., the way we view the world and reality will inform the way we go about acquiring information/data about that world and reality, and how we understand or interpret and use or disseminate that information/data (Babbie, 2020; Creswell, 2013). Hence, it is no surprise that knowing about one’s epistemology enables us to make sense of the way we approach research, how we seek to find answers to our research questions, what we value as being knowledge that can be trusted and phenomena that is worthy of further investigation (Babbie, 2020). Some scholars say that epistemologies capture our ‘ways of doing’ and that such ways can range from being ‘objective’ to being ‘subjective’ (Saunders et al., 2019).

As an example of an epistemological stance, a scholar of Management with an interpretivism stance believes and thinks that knowledge is constructed by humans through their own experiences, social interactions and interpretations (Table 6.1). Hence, such a stance emphasises the nature of human experiences and the meanings that humans attach to those experiences; and so, underlines the subjective nature of the associated research of interpretivist researchers. For example, a researcher studying the organisational culture of hotels may use qualitative methods such as ethnography to explore the lived experiences of frontline hotel workers to gain a deeper and richer understanding of the nature and characteristics of the organisational culture of hotels (Pryce, 2005).

Axiology

Another term closely related to ontology and epistemology is ‘axiology‘. It refers to the researcher’s considerations of their values and how issues of right or wrong are dealt with (Creswell, 2013; Guba & Lincoln, 1994). Axiology takes into account perceptual biases and influences the researcher in the values that they assign to their research (Table 6.1). Essentially, the axiological stance of a researcher relates to their values, beliefs and ethical positions and how this informs the research. It focuses the researcher to think about aspects such as the cultural and intercultural issues of the research, the conduct of the research in a respectful way, and the minimising of risk to participants and researchers (Babbie, 2020; Guba & Lincoln, 1994). Axiology is concerned with what “we believe is true in terms of moral choices, ethics and normative judgements” (Pabel et al., 2021, p. 6).

As an example of an axiological stance, a scholar of Management may take a customer-centeredness approach when looking at how institutions/organisations are taking steps to address climate change. In such a case, the researcher may utilise qualitative research methods (perhaps semi-structured interviews) to examine to what extent customers consider an institutions/organisations initiatives in responding to climate change before they purchase from the institution/organisation.

Time Horizon

In developing the research design, another aspect to consider is the ‘time horizon’. Thought should be given to whether the research is a ‘snapshot’ in time (i.e., cross-sectional) or whether it extends over a period (i.e., longitudinal studies) (Saunders et al., 2019). Both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies can involve quantitative, qualitative or mixed methods approaches. The life of the project would determine if the research is cross-section or longitudinal.

6.2 Approach to Theory Development

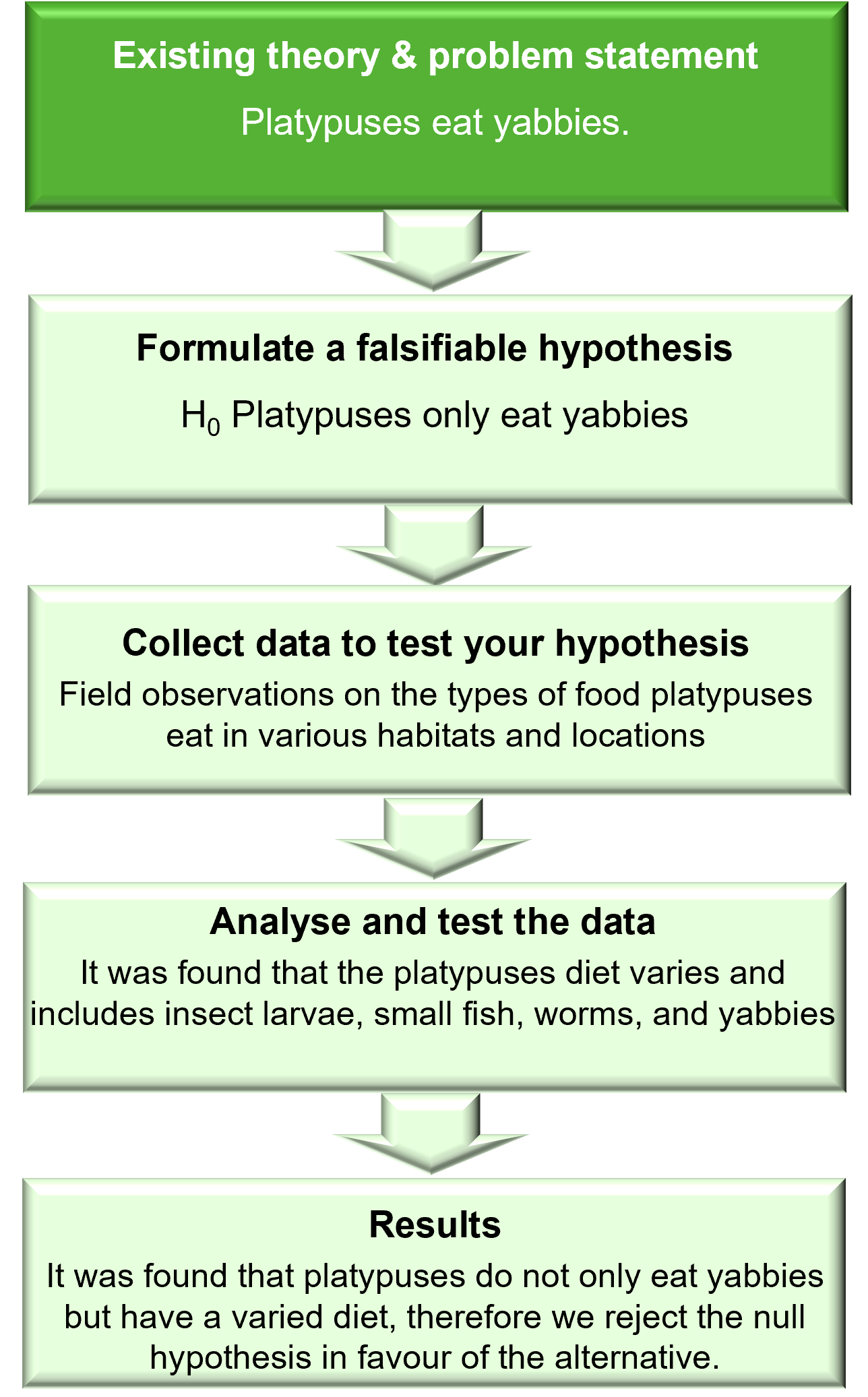

Deduction

- An existing theory and problem statement,

- You develop one or more falsifiable hypotheses,

- You then observe or experiment to collect data to test the hypothesis,

- Analyse and test the data,

- Results – accept or reject your hypothesis (Mauldin, n.d.).

Figure 6.1 provides an example of deductive reasoning in relation to platypuses’ diets, remembering that deductive reasoning provides a specific (certain) conclusion.

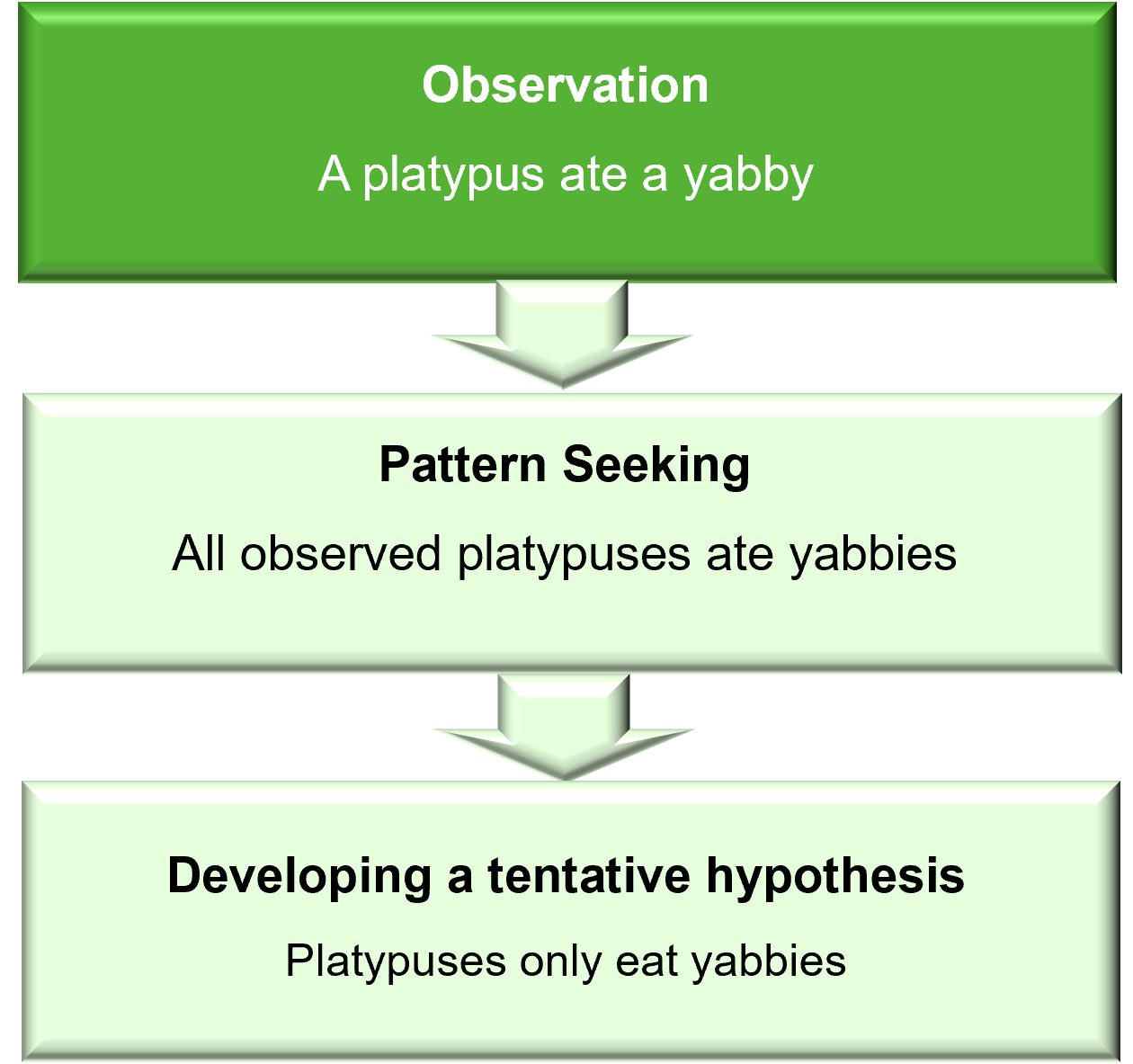

Induction

With inductive reasoning, you begin with your observations, look to identify patterns, develop a tentative hypothesis and then test your theory (Mauldin, n.d.). Figure 6.2 shows an example of inductive reasoning in relation to platypus diets, remembering that inductive reasoning provides a specific observation and general (probabilistic) conclusion.

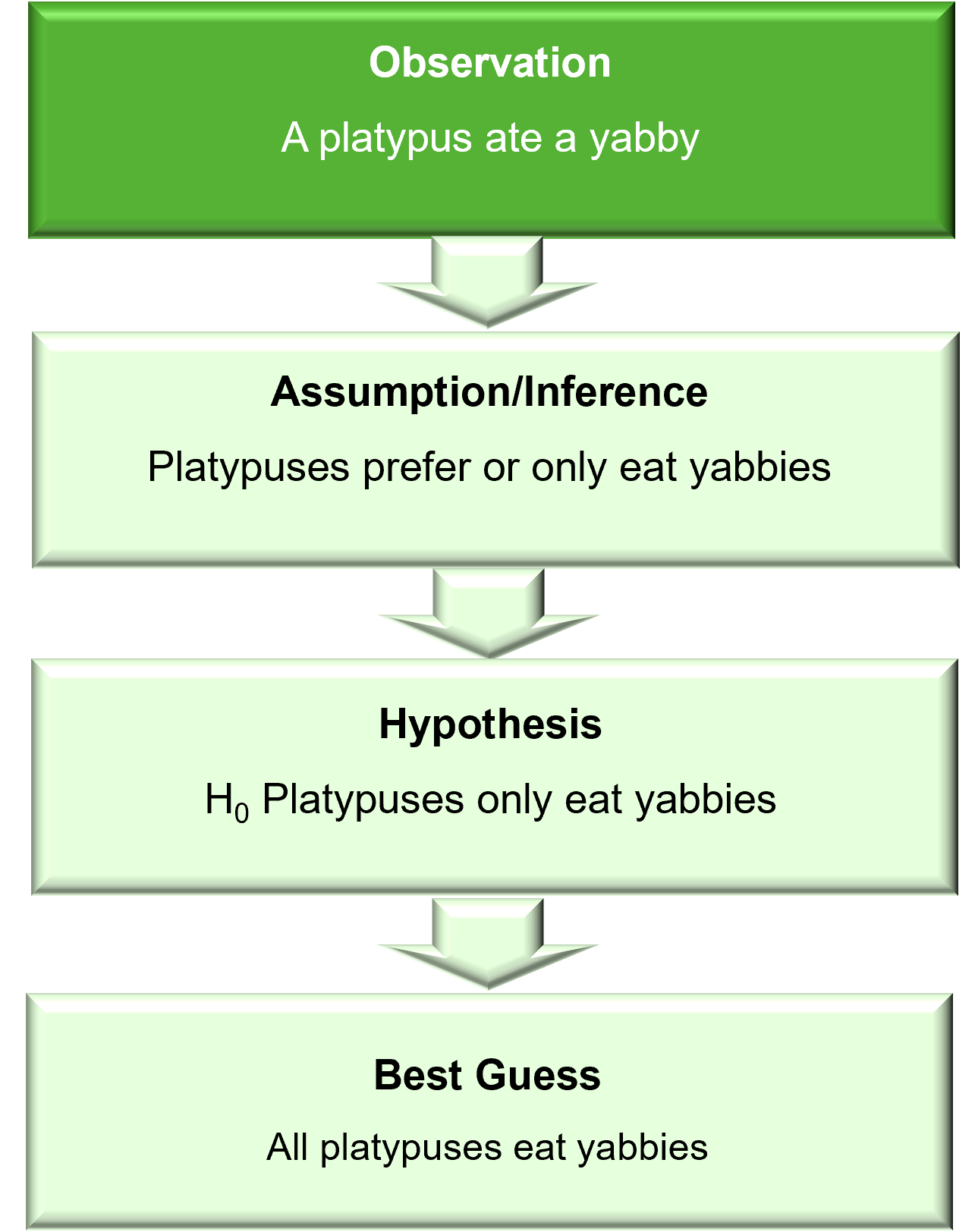

Abduction

Abductive reasoning is a combination of deductive and inductive reasoning. It generally begins with an incomplete set of observations and then proceeds to the likeliest possible explanation. Abductive reasoning is used in daily decision making where information is often incomplete, but a decision needs to be made. For example, in the medical field, when a person comes in and describes their symptoms, the medical practitioner looks for the diagnosis that best explains most of the symptoms (Butte College, n.d.). Figure 6.3 provides an example of abductive reasoning when you do not have all the available information. Abductive reasoning has incomplete observations; therefore, the result is the best prediction (probabilistic).

Key Takeaways

- The conduct of research is based on how researchers see the world and reality.

- Research paradigms refer to the philosophical beliefs and assumptions that underlie the researchers’ approach to research and so, the development of knowledge.

- There is no single best research philosophy or paradigm. Rather, it is based on the researcher’s stance in terms of ontology, epistemology and axiology.

- Deductive reasoning begins with an existing theory and problem statement and comes to a specific conclusion.

- Inductive reasoning begins with an observation and has a general conclusion.

- Abductive reasoning is a combination of deductive and inductive reasoning, starting with observation and ending with a best prediction (best guess).

References

Babbie, E. R. (2020). The practice of social research (15th ed). Cengage Learning.

Butte College. (n.d.). Deductive, inductive, and abductive reasoning. https://www.butte.edu/departments/cas/tipsheets/thinking/reasoning.html

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating (4th Ed). Pearson Education.

Creswell, J.W., Hanson, W. E., Clark Plano, V. L., & Morales, A. (2007). Qualitative research designs: Selection and implementation. The Counselling Psychologist, 35(2), pp. 236-64. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000006287390

Crotty, M. J. (1998). The foundations of social research: Meaning and perspective in the research process. Allen & Unwin.

Guba, E. G., & Lincoln, Y. S. (1994). Competing paradigms in qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 105–117). Sage Publications.

Lincoln, Y. S. & Guba, E. G. (2007). Paradigms. In G. Ritzer (Ed.), The Blackwell encyclopedia of sociology (pp. 3355-3356). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781405165518.wbeosp001

Mauldin, R. L. (n.d.). Foundations of social work research. University of Regina. https://opentextbooks.uregina.ca/foundationsofscoialworkresearch/

Pabel, A., Pryce, J. & Anderson, A. (2021). Research paradigm considerations for emerging scholars. Channel View Publications. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781845418281

Pryce, J. (2004) An examination of the influence of organisational culture on the service predispositions of hospitality workers in tropical North Queensland [PhD thesis, James Cook University]. ResearchOnline. https://researchonline.jcu.edu.au/1379/

Reese, W. L. (1980). Dictionary of philosophy and religion. Humanities Press.

Rohmann, C. (1999). A world of ideas: A dictionary of important theories, concepts, beliefs, and thinkers. Ballantine Books.

Saunders, M., Lewis, P., & Thornhill, A. (2019). Research methods for business students (8th ed.). Pearson Education.

Tashakkori, A. & Teddlie, C. (2003). Handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioral research. Sage.