Research Strategy

Learning Objectives

In this chapter you will:

- recognise and understand that there are numerous research strategies to consider when designing your research.

- understand that there is a basic application for each strategy.

Research Strategies

Action Research

Action research is associated with social systems where members of the community, organisations (groups) are participating in the research (McNabb, 2021; Rapoport, 1970). When businesses are undergoing radical changes, such as redundancies, action research may assist everyone to more fully understand what is happening and why.

There are several versions of action research, for example:

-

Canonical Action Research is based on five principles:

- The researcher-client agreement – the client must understand how this type of research works, including positives and negatives.

- The cyclical process model – this includes starting the process, planning, intervention, evaluation, and reflection, prior to either continuing for another cycle or being satisfied with results from the first cycle.

- Theory – can begin with no theory but move to theorising as the research progresses.

- Change through action – when a problem has been identified through action then change can occur.

- Learning through reflection – continuous learning occurs and is shared throughout the research (Davison et al., 2004).

-

Educational Action Research is based on the following for classroom consideration:

- The process aims to improve educational practice. Methods involve action, evaluation, and reflection. This process gathers evidence allowing change in practices to be implemented.

- The process is undertaken collaboratively by individuals with a common purpose.

- Situation and context based.

- Interpretations made by participants aid in the development of reflective practices.

- Action and application lead to the creation of knowledge.

- Can be problem solving – the solution provides improvement in practice.

- It is iterative, you can come back to any point in the process, if something has not worked as expected change the approach and try again. This creates an ongoing process of reflection and revision.

- As actions develop and are implemented findings begin to emerge, they are not conclusive, they are ongoing (Spencer-Clark et al., n.d.).

Archival Research

Archival research uses data that are already in existence prior to the researcher(s) beginning their study. The researcher’s first decision is deciding which information is required, and the most appropriate way to analyse it (Timothy, 2012).

-

Archival data can be in a variety of formats, for example:

- numerical data sets collected by someone else for a different purpose

- artefacts

- texts, for example, a library collection

- government records

- personal notes, memos, and other written and digital information

- photographs

- illustrations

- art works

- film

- video.

Research fellowships and residencies with the State Library of Queensland are examples of archival research taking place.

Case Study Research

Case studies can be descriptive, explanatory, or exploratory. A case study is the investigation at a deeper level of one individual subject (Martelli & Greener, 2018), for example: Harley Davidson Motorcycles; Mozart; Greenland, etc.

However, there are other views on case studies, with some believing there are three distinct types:

- Instrumental case studies which are exploratory, seeking to provide understanding of a topic/problem rather than focusing on the case itself.

- Intrinsic case studies are undertaken when a researcher finds the case of particular interest, and where deeper knowledge of the topic/problem may occur.

- Collective case studies are also known as cross-case studies due to the research focusing on one particular topic/problem but across multiple places. For example, populist world leaders are the focus, in an effort to understand their approaches to democracy (McNabb, 2021).

Correlational Research

Correlational research seeks relationships between variables, these could be statistical relationships. In this instance if one variable changes, another variable also changes, although it might not be in the same direction. Just because these variables are associated, it does not then lead to a causal relationship. For example, university students often miss Monday’s 8.00am class. You cannot then conclude that the early class time has a causal impact on attendance. Further research is required to provide any definite conclusions. The statistical method used for correlational research is correlational coefficients (Martelli & Greener, 2018).

Cross-sectional Research

There are several varying views on cross-sectional research, all depending on the field of study, for example:

- Cross-sectional research, in relation to business, could be looking from the standpoint of several employees at a point-in-time on how they use Artificial Intelligence (AI) in the workplace (Martelli & Greener, 2018).

- Cross-sectional research is a common approach used in health and medicine (Horrigan et al., 2013).

- Cross-sectional research is observational, no manipulation of variables occurs, this is a snapshot of what is happening at that exact time (Wang & Chen, 2020).

Descriptive Research

Descriptive research, as it sounds, describes something. Often this type of research is collecting data that describes the characteristics of people, events, or situations. Descriptive research can be quantitative or qualitative (Sekaran & Bougie, 2013).

To develop an accurate profile of events, persons, or a situation the descriptive research often asks questions that begin with or contain one of the following:

- Who?

- What?

- When?

- Where?

- How?

In general, descriptive research is analysed using descriptive statistics, such as mean, median, mode, skewness, kurtosis, standard deviation, etc., (Martelli & Greener, 2018).

There are two types of strategies that can be used for descriptive research, field studies or field surveys. Field studies contain fewer issues or items but investigate to a greater depth than field surveys. Field surveys are a popular way to gather data as they are reasonably easy to design and distribute. Both types of studies provide data that are used as numeric descriptors (McNabb, 2021).

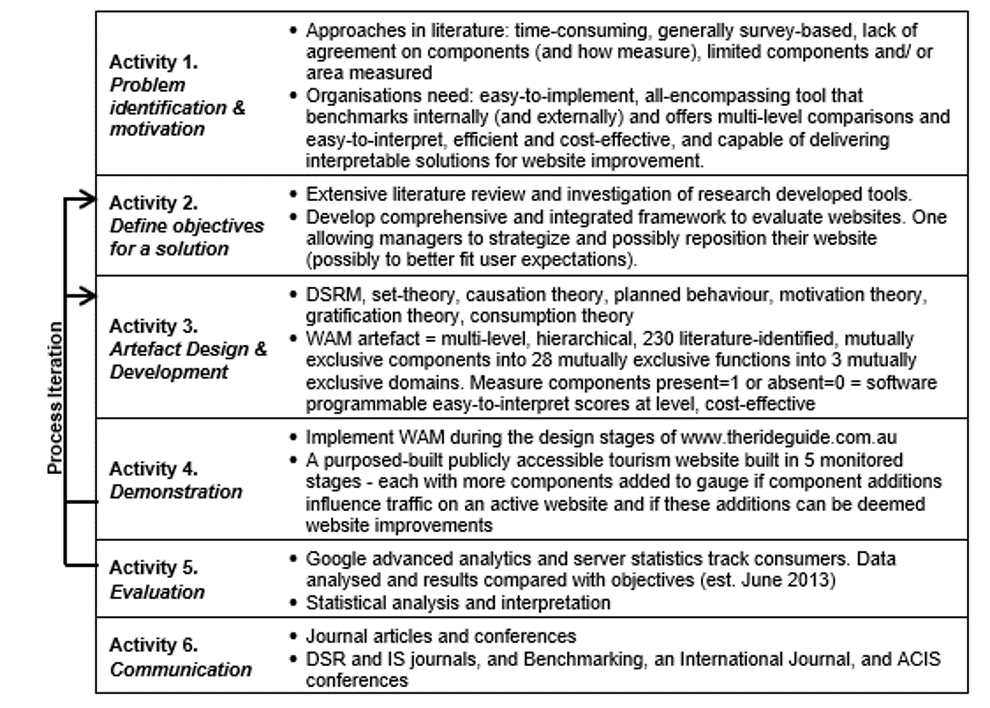

Design Science Research

In a seminal paper published in 2010, Hevner and Chatterjee provide the following definition of Design Science:

Design science research allows a designer to answer questions relevant to human problems via the creation of innovative artefacts – thereby contributing new knowledge to the body of scientific evidence. The designed aretefacts are both useful and fundamental in understanding that problem. (p. 5)

Design science research has a methodology (DSRM) that is iterative; it consists of six steps or activities, they are:

- Problem identification and motivation – you need to define the problem you have identified and a motivation for solving the problem.

- Define objectives for a solution – you need to define and discuss what a better artefact* would achieve than what already exists.

- Artefact design and development – here you design and develop the new artefact.

- Demonstration – here you use and test the new artefact.

- Evaluation – you observe how effective and efficient the new artefact is, here you can refine your artefact by returning to steps 2 or 3.

- Communication – you now publish your results in scholarly and professional publications (Peffers et al., 2007).

*The artefact is useful and fundamental in understanding the problem.

This DSRM approach has been used in information systems research for many years. However, it is only in recent years that it has made its way fully into other areas of research. For example, in business, in the development of a website benchmarking artefact (Cassidy, 2015; Cassidy, 2021).

In the case of website benchmarking, the artefact produced was a website analysis method (WAM). WAM contains a universal set of website components that can be used to assess a website (Cassidy & Hamilton, 2016). Figure 7.1 outlines the steps taken in the development of WAM.

Ethnography Research

Ethnography is a methodological tool used to study cultural phenomena of a group or sub-group (Hayre & Hackett, 2021). Ethnography can be a written account of a particular group or sub-group, or it can be field work, where the researcher(s) spend an extended amount of time with the group or sub-group in the hope of generating new cultural insights (Adams, 2012).

Ethnography or ethnographic research may use several additional research techniques, such as questionnaires, structured interviews, unstructured interviews, focus groups, video recording, or photographs. When conducting ethnographic research, the researcher(s) must leave any preconceptions (biases) behind (Adams, 2012).

Louis Theroux’s documentary series where he is embedded with the people/groups he is exploring is a type of ethnography research, videos are available on ABC iView.

Experimental Research

This is a type of quantitative research. Experimental research uses independent variables, and dependent variables to test if, and how, manipulation of the independent variable(s) affect the dependent variable (Bhattacherjee, 2019). For further information, see the Data Collection and Analysis chapter.

Explanatory Research

Explanatory research is used when the researcher is attempting to identify the cause-and-effect two or more variables they are studying, attention must be paid to any possible confounding and modifying variables (Bentouhami et al., 2021; DeCarlo et al., n.d.).

The three main steps to explanatory research are:

- Define the problem – what is it that you want to know more about?

- Gather data – can be via experiments, surveys, interviews, observations, or focus groups.

- Analyse the data – this could be done with regression analysis, Chi-Square, T-test or ANOVA

For explanatory research using case studies there are six steps:

- Organise data

- Look for and develop categories, themes, and patterns

- Code the data by refining the categories, themes and patterns that emerged in step two

- Apply the codes to the data

- Investigate and seek alternative explanations

- Communicate results. (McNabb, 2021)

Explanatory research allows for a more in-depth understanding of the problem (issue), identifying possible causes and solutions to the problem; however, it can be time-consuming, especially when used with grounded theory (McNabb, 2021).

Exploratory Research

Exploratory research is generally used in the first instance when there has been very little prior research conducted, therefore, not much is known about the topic of interest or there is very little information on how similar problems (issues) have been solved previously. This approach tests the feasibility and justification of undertaking a larger study (DeCarlo et al., n.d.).

The main qualitative data collection techniques are:

- focus groups

- literature searches

- case studies

- interviews with a key group of experts (the Delphi Method). (McNabb, 2021)

Grounded Theory

Grounded theory research is a qualitative approach to research. Here, the researcher(s) focus on the social experiences of people and their inherent realities. The study does not begin with a theory as there are no preconceptions, theory emerges from the research process of information gathering, which may be in the form of experiential stories from respondents, and from the interpretation of those stories (Junek & Killion, 2012).

Grounded theory research has the following steps:

- The researcher(s) focusing on an area of interest, in behavioural, social, or administrative sciences areas, for example, a phenomenon, circumstance, trend, behaviour, etc.

- Purposive sampling is used for data collection by observation, and/or interviewing.

- Analysis requires data to be grouped into categories, and codes are assigned.

- Data are continually compared to data in other categories to hopefully generate a theory (Tie et al., 2019).

The researcher(s) are organising and applying structure to the data which is achieved by employing a set of researcher-determined groups and categories. Linkages between categories are identified.

Internet-Mediated Research

Internet-mediated research does not treat the internet as a subject for research, but rather as a medium, where research can be conducted.

For example:

- online surveys

- online interviews

- archives

- data scraping

- social media conversations and observations

- content analysis of websites or webpages

- blogs

- discussion boards

- reviews

- virtual worlds (e.g., Second Life)

- gaming

- chatrooms

- software, coding, and technologies

- interfaces

- Internet of Things (IoT) connections, etc. (Anabo et al., 2018; UK Research Integrity Office, 2016)

Narrative Research

Narrative research is research that may use narrative materials such as video games, novels, films, and speeches that already exist. The researcher(s) may ask participants to produce stories, these may be oral, photographic, self-portraits, or journals of events, and these are also forms of narrative material (Squire et al., 2014). However, there are no definite starting or finishing points in narrative research, as there has been continuous debate on what definition of ‘narrative’ should be used. Narrative research basically, as yet, has no defined set of rules covering how to conduct this type of research (Andrews, 2021).

The following are some important things to consider with narrative research:

- the story must mean something

- these stories are a rich source of information in our attempts to understand people, and indeed, the world around us

- it is ‘messy’, and it is not always clear what is, and what is not data

- the story, and when it happened, are bound together; one does not have meaning without the other. (Andrews, 2021)

Assessing the quality of narrative research:

- You hope for truthfulness. You may not be able to verify the story given to you, but you hope it is true, or at least the person who provides it believes it to be true. With public figures, you would generally expect some embellishments or omissions in their narratives.

- The reader believes that the researcher(s) are trustworthy. This can be strengthened when the researcher(s) theoretical claims are supported by respondents’ accounts, including any negative cases, and alternative interpretations are presented.

- Critical reflexivity – researcher(s) need to indicate the positioning of their personal situated knowledge in relation to the investigation. This is where a researcher’s biography is valuable.

- Scholarship and accessibility – although it can be difficult to achieve both, research output should be scholarly and accessible. Always ensure you are writing for the audience you are targeting. If a journal it would require more theoretical discussion than a report to an organisation.

- Ethical sensitivity (see Chapter 1) in this text for ethics requirements in research).

- Meaning in the narrative is co-constructed – the meaning of the narrative can be remade by the participant (at any point), the researcher (at any point), the story transcriber, and even the person reading the final output.

- The researcher(s) must consider what is not said in addition to what is said. Look closely at the research design. Is everyone included that should be? What kind of stories are being encouraged by the researcher(s)? Are there untold stories? You may find clues to these from participants’ body language. Untold stories can affect the interpretation of the stories that are told.

- The researcher(s) need to understand temporal fluidity – narrative research tends to shift around, and researchers must understand this: ‘life does not stand still. ’ Expecting the social world to hold still for a ‘snapshot’ may seem like reducing the flow to frozen moments of a realist’s description. Narrative research needs to confront these ‘frozen moments’ in the analysis, paying close attention to the contents of the gathered data.

- Attention must be given to the fact that stories are multilayered; they do not exist in isolation; they are always connected to other stories in some way. The researcher(s) need to investigate the coexistence of stories and how they are interconnected at the macro and micro levels.

- The researcher(s) must provide contextualisation of the research. Consideration and understanding must be given to the fact that stories are produced in specific contexts, at a particular point in time, for a particular audience in analysing the data collected (Andrews, 2021).

Phenomenology Research

The “phenomenon” in phenomenology is a social construction of a group of people. Everyone has their own worldview. This worldview is constructed from our specific beliefs, our specific values, and our experiences which we attach meaning to. Researcher(s) endeavour to understand these different worldviews and what has contributed to them at a deeper level, producing richer information (Alele & Malau-Aduli, 2023).

Phenomenology research sees the researcher(s) setting aside any understanding or belief of the phenomenon under study (Martelli & Greener, 2018). To this end, they focus on theme analysis (Alele & Malau-Aduli, 2023). When used in interviewing, it is a combination of life history and in-depth interviewing (McGehee, 2012). Phenomenology is a common form of qualitative research producing richer, deeper, more complex understanding of the phenomena under study (Alele & Malau-Aduli, n.d.).

Survey Research with Questionnaires

Survey research with questionnaires is where the questionnaire contains a standardised set of questions: every participant in the study has exactly the same set of questions in exactly the same order (standardised). The only change to this occurs when ‘filter’ questions are included. This when the participant (respondent) ceases their completion of the questionnaire and is either directed to move to a question out of sequence, or to resume and continue as before. The survey can be conducted face-to-face where the researcher reads the questions out to the respondent and marks the answer, or the researcher hands the respondent the questionnaire for them to complete and return. Online, where the respondent clicks on a link to take them to the electronic survey, or in the case of a Census, online or hand-delivered for later collection (Sallis et al., 2021).

Survey research allows the researcher(s) to collect data that can be analysed quantitatively (with Excel, SPSS, or R) using descriptive and inferential statistics. The data can be used to suggest a possible relationship between variables and produce models of these relationships (Manning & Munro, 2007). When conducting survey research, time needs to be spent determining the sample size for the study (discussed further in Chapter 10). Further detail on surveys is provided in the next chapter.

Key Takeaways

-

There are numerous research strategies that you can consider for any research undertaken.

- Each type of research strategy has a basic application.

References

Adams, K. M. (2012). Ethnographic methods. In L. Dwyer, A. Gill, and N. Seetaram (Eds.). Handbook of research methods in tourism, quantitative and qualitative approaches (pp. 339-351). Edward Elgar Publishing.

Alele, F., & Malau-Aduli, B. (2023). An introduction to research methods for undergraduate health profession students. James Cook University. https://jcu.pressbooks.pub/intro-res-methods-health/chapter/4-3-qualitative-research-methodologies/

Anabo, I. F., Elexpuru-Albizuri, I., & Villardon-Gallego, L. (2019). Revisiting the Belmont Report’s ethical principles in internet-mediated research: Perspectives from disciplinary associations in the social sciences. Ethics and Information Technology, 21, 137-149. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10676-018-9495-z

Andrews, M. (2021). Quality indicators in narrative research. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 18(3), 353-368. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2020.1769241

Bentouhami, H., Casas, L., & Weyler, J. (2021). Reporting of “theoretical design” in explanatory research: A critical appraisal of research on early life exposure to antibiotics and the occurrence of asthma. Clinical Epidemiology, 13, 755-767. https://doi.org/10.2147/CLEP.S318287

Bhattacherjee, A. (2019). Social science research: Principles, methods and practices (Rev. ed.). USQ Pressbooks. https://usq.pressbooks.pub/socialscienceresearch/chapter/chapter-10-experimental-research/

Cassidy, L. (2015). Website benchmarking: A tropical tourism analysis [Doctoral thesis, James Cook University]. ResearchOnline. https://researchonline.jcu.edu.au/41251/

Cassidy, L. (2021). The design science research paradigm: An instantiation of website benchmarking. In A. Pabel, J. Pryce, & A. Anderson (Eds.), Research paradigm considerations for emerging scholars (pp. 25-37). Channel View Publications. https://doi.org/10.21832/PABEL8274

Cassidy, L., & Hamilton, J. (2016). A design science research approach to website benchmarking. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 23(5), 1054-1075. https://researchonline.jcu.edu.au/34970/7/34957%20Cassidy%20and%20Hamilton%202016_accepted%20version.pdf

Davison, R., Martinsons, M. G., & Kock, N. (2004). Principles of canonical action research. Information Systems Journal, 14(1), 65-86. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2575.2004.00162.x

DeCarlo, M., Cummings, C., & Agnellie, K. (n.d.). Graduate research methods in social work. Pressbooks. https://pressbooks.rampages.us/msw-research/chapter/2-starting-your-research-project/

Hayre, C. M., & Hackett, P. M. W. (2021). Handbook of ethnography in healthcare research. Routledge.

Hevner, A., & Chatterjee, S. (2010). Design research in information systems: Theory and practice. Springer.

Horrigan, J. M., Lightfoot, N. E., Lariviere, M. A. S., & Jacklin, K. (2013). Evaluating and improving nurses’ health and quality of work life. Workplace Health and Safety, 61(4) 173-188.

Junek, O., & Killion, L. (2012). Grounded theory. In L. Dwyer, A. Gill, & N. Seetaram (Eds.), Handbook of research methods in tourism: Quantitative and qualitative approaches (pp. 325-328). Edward Elgar Publishing.

Manning, M., & Munro, D. (2007). The survey researcher’s SPSS cookbook. Pearson.

Martelli, J., & Greener, S. (2018). An Introduction to business research methods (3rd ed.). Bookboon. https://bookboon.com/en/an-introduction-to-business-research-methods-ebook

McGehee, N. G. (2012). Interview techniques. In L. Dwyer, A. Gill, & N. Seetaram (Eds.), Handbook of research methods in tourism: Quantitative and qualitative approaches (pp. 365-376). Edward Elgar Publishing Limited.

McNabb, D. E. (2021). Research methods for political science: Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed method approaches (3rd ed.). Routledge Taylor and Francis Group.

Peffers, K., Tuunanen, T., Rothenberger, M. A., & Chatterjee, S. (2007). A design science research methodology for information systems research. Journal of Management Information Systems, 24(3), 45-77.

Priya, A. (2021). Case study methodology of qualitative research: Key attributes and navigating the conundrums in its application. Sociological Bulletin, 70(1). 94-110.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0038022920970318

Rapoport, R. N. (1970). Three dilemmas in action research. Human Relations, 23(6), 499-513.

Sallis, J. E., Gripsrud, G., Olsson, U. H., & Silkoset, R. (2021). Research methods and data analysis for business decisions: A primer using SPSS. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-84421-9

Sekaran, U., & Bougie, R. (2013). Research methods for business: A skill-building approach (6th ed.). John Wiley and Sons.

Spencer-Clark, J., Porath, S., Thiele, J., & Jobe, M. (n.d.). Action research. New Prairie Press Open Book Publishing. https://kstatelibraries.pressbooks.pub/gradactionresearch/

Squire, C., Davis, M. M. D., Esin, C., Andrews, M., Harrison, B., Hyden, L., & Hyden, M. (2014). What is narrative research? Bloomsbury.

Tie, Y. C., Birks, M., & Francis, K. (2019). Grounded theory research: A design framework for novice researchers. SAGE Open Medicine, 7, 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050312118822927

Timothy, D. J. (2012). Archival research. In L. Dwyer, A. Gill, & N. Seetaram (Eds.), Handbook of research methods in tourism: Quantitative and qualitative approaches (pp. 403-416). Edward Elgar Publishing.

UK Research Integrity Office. (2016). Good practice in research: Internet-mediated research (Version v1.0). https://ukrio.org/wp-content/uploads/UKRIO-Guidance-Note-Internet-Mediated-Research-v1.0.pdf

Wang, X., & Cheng, Z. (2020). Cross-sectional studies: strengths, weaknesses, and recommendations. CHEST Journal, 158(1), 65-71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2020.03.012