Surveys and Interviews

Learning Objectives

In this chapter you will:

- understand and recognise that writing a questionnaire requires considerable planning

- understand the importance of writing good questions

- discover problems that can occur when writing questions

- recognise the difference between open-ended and closed questions and their uses

- understand and recognise the differences and uses for categorical questions, semantic differential scales, interval scales, ratio scales, and Likert scales

- learn the differences between a structured interview, a semi-structured interview, and an unstructured interview.

Surveys or Questionnaires?

You are often going to find the terms survey and questionnaire used interchangeably. In this chapter we use questionnaire in relation to design and survey in relation to the distribution or ‘surveying’ of people.

8.1 Questionnaire Design

Before designing your questionnaire, think about your research focus, what do you want to measure, and who the target population is. For example, is the target population based on a specific demographic, (e.g., Gen Y, Gen Z, Baby Boomers, etc.), or is it based on location or some other factor? Then determine how you are going to collect the data, self-completion, online, face-to-face interviews, email, telephone etc.

Questions for your study can come from an existing questionnaire or questionnaires within the published literature, from your organisation, or your industry. These questionnaires can be adapted to suit your study, or you can develop your own. The opening question should not be difficult, nor overly personal, you do not want to put the potential participant off. On the other hand, do ensure you have your most important questions reasonably early in the questionnaire to ensure that even when the respondent does not complete every question their answers may still be useful. Be very careful of using multiple choice in your questionnaire as this can encourage respondents to do a ‘tick and flick’ set of answers which in the end can skew your results.

Questionnaires do not just contain the questions relating to your study focus. As per your ethics requirements, you must provide potential respondents with a ‘participant information sheet’ this includes the name of your project, what is required of the participant, the protocols, how respondents are recruited, and details of the principal researcher. An informed consent form must also be completed by the respondent and retained by the researcher(s), it must be explained to the potential participant that their personal details do not form part of the study, is not retained with their completed questionnaire, and the information is only retained as part of ethics requirements. The informed consent form has the principal investigator (researcher), the project title, the university college, what is being agreed to, Yes/No boxes for consent, and a section for the participan’s name, signature, and date.

Your questions must include instructions on how to answer each question, e.g., place a check in only one box; circle only one answer; circle all that apply; number in order of importance etc. Some questions may require further explanation depending on the exact type of question.

There are several question types, for example:

- A factual question about attributes – e.g., How many cars do you own?

- An attitude question – e.g., Do you think politicians should have their parliamentary pension frozen until they are no longer working?

- A beliefs question – e.g., Do you believe the Loch Ness monster really exists?

- A behaviour question – e.g., Which Australian state and territory capital have you visited in the last 2 years?

In general, questionnaires have questions that request demographic information. Depending on the importance of the information the questions may be situated at the beginning of the questionnaire, towards the end of the questionnaire, or divided between both positions.

Demographic information includes:

- Age – while some are happy to provide their age others are not. However, they are happy to provide the year they were born or the age range they fall into.

- Gender – this should not be only male/female, provide an alternative where respondents can specify how they view themselves.

- Town/country they live in, you may include ‘for how long’ depending on the importance of the information. This can be useful for tourism studies.

- Ethnicity can be a tricky question to ask, for example, in the USA you may have people identify as Irish-American, however the Irish may be from the 1700s. Another option might be to ask their cultural identity, which could link back to a question on how long they had lived in a town/country.

- When asking about employment you may need to be specific about type of employment if this is important to your study.

- As with age, people do not generally provide an answer to ‘how much do you earn in a year’ or ‘what is your yearly income’, these types of questions often go unanswered, or the answer provided is not true. Try using an income range if this is important to your study.

Any demographic questions asked need to be closely related to your target population and the overall aim of the research. Do not ask the question if you do not need the answer.

Categorical Questions

Categorical questions have answers that contain categories. Depending on the question(s), the respondent may select:

- only one answer (category), or

- multiple answers (multiple categories).

- When the categories are No/Yes, the question is referred to as a dichotomous (or binary) question.

A dichotomous, categorical question is referred to as a nominal scale in relation to data analysis. These answers are coded as either ‘0’ or ‘1’ for data analysis. When a categorical question has one category that can be seen as ‘larger’ than the previous, but not how much larger, such as ‘highest form of educational qualification’ the scale is ordinal for data analysis (Manning & Munro, 2007).

Semantic Differential Scales

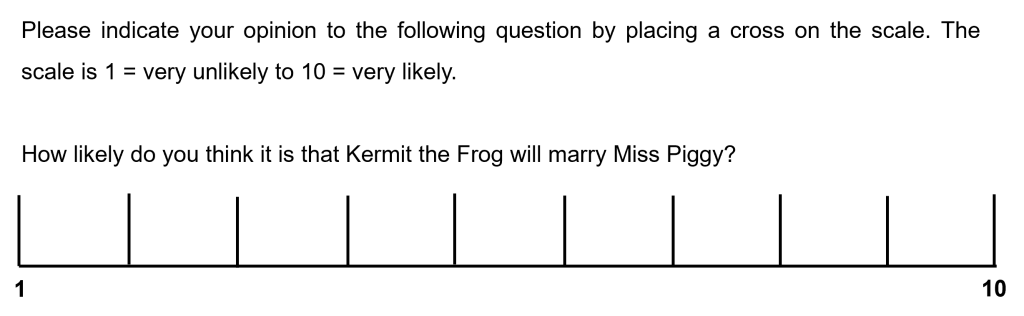

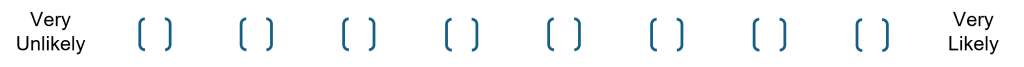

A semantic differential scale has two opposite key word anchors with spaces between for respondents to indicate their opinion. The scale may be 5-point, 7-point, or 10-point. For example (Figure 8.1):

As seen in Figure 8.1, respondents are requested to indicate their opinion on a scale with anchored opposites. The scale indicators can be indicated in a variety of ways, another option is Figure 8.2.

There is some debate amongst researchers on semantic differential scales. One group believes the scale to be equidistant and therefore can be seen as interval data. While another group is of the opposite view, they see the scale to be arbitrary, and therefore the data are ordinal. As there is a lack of agreement on the semantic differential scale it has dropped out of favour and is now, not often used (McNabb, 2021).

Interval Scale

Interval scale data is continuous data and can be measured (Chapter 5). With the interval scale, points on the scale can be arranged in a definite order and the scale increments are the same throughout the scale. For example, using calendar years as an interval scale. However, zero on an interval scale is not a true zero, as discussed in Chapter 5.

Ratio Scale

Ratio scale data is continuous data and can be measured (Chapter 5). The difference between points on a ratio scale are meaningful, as zero is a true zero, as discussed in Chapter 5.

Likert Scales

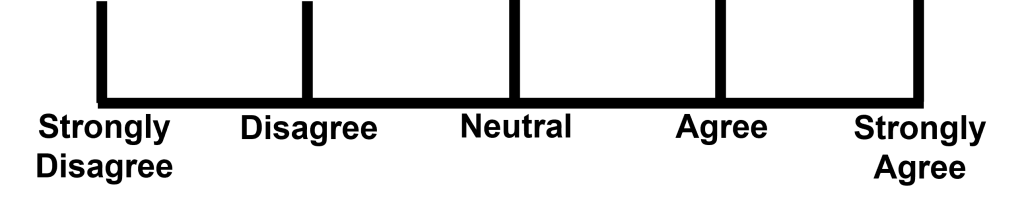

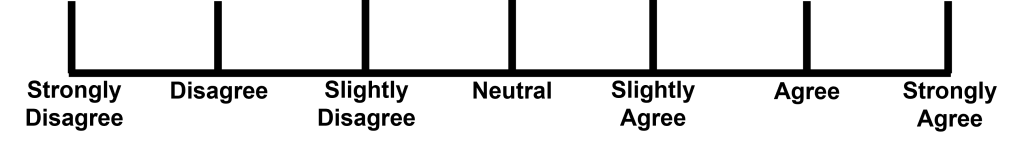

Likert Scales measure a respondent’s attitude, generally the extent they agree or disagree with a statement or set of statements. Although not interval data, researchers often treat Likert scale data as such, they do this to obtain the mean.

Likert scales should have an odd number of points to allow a neutral position in the middle. Researchers have used Likert scales with 3, 5, 7, and even 15 points but too few or too many points are not appropriate. Less than 5 points does not give you suitably granular feedback, and more than 7 points can discourage respondents from answering the question as they are required to spend an excessive amount of time considering their position on the scale.

A Likert scale may use a satisfaction rating, for example, 5-point or 7-point (Figures 8.3 and 8.4). If you look more closely at Figure 8.3 you may begin to understand that a 3-point scale would provide little information, and you might as well ask a dichotomous question. Looking at Figure 8.4, imagine if you had a nine-point scale, what other attitudes would you include, ‘moderately disagree’ and ‘moderately agree’? What about a fifteen-point Likert scale? Researchers must put a lot of thought into using Likert scales and the number of attitude options they use.

Researchers must also be very careful when writing the Likert scale questions, they need to be very specific about what they want to know, for example, it is pointless just asking how satisfied someone is with the restaurant customer service as it is not specific. Does customer service relate to waitstaff, bar staff, speed of service, how long it took to be seated etc. But what about satisfaction with the food, the quality of drinks, and so on? To ensure results are meaningful the researcher(s) may be required to break the initial question down into more specific and targeted questions.

Open-Ended Questions

Open-ended questions do not have a selection of pre-determined answers, they have a space to allow respondents to answer in their own words. The researcher is seeking extra, more textual information. However, this type of data can be difficult to analyse as no two respondents are going to provide exactly the same answer. Therefore, open-ended questions are should be used sparingly in questionnaires.

Problems to Avoid When Writing a Question

Double-Barrelled Questions

The question asks for feedback or opinions on two different issues or topics within one single question.

When the respondent can only select one answer (closed questions), your data is going to be skewed.

For example: Do you like bacon and eggs for breakfast? This could be split into two simple Yes/No questions. Do you like bacon for breakfast? Yes/No; Do you like eggs for breakfast? Yes/No.

Unclear Terms

You need to think about what the average person would think when they read your question.

For example: a questions asks – Do you drink often? What is this question asking? What is meant by often? What is meant by ‘drink’? Does drink mean fluid in relation to staying hydrated?

To counter any issues researchers should conduct a limited test of their questionnaire prior to distribution to their wider target audience.

In limited testing the respondents can ask for clarification, or comment on problems they perceive with the questions, this strengthens the questions and in turn the study.

Leading or Loaded Questions

Leading or loaded questions contain in-built bias, an opinion, or non-neutral language. This can potentially influence the way the respondent answers.

For example, when someone cuts you off in traffic, which of the following do you do?

- speed up and tailgate them

- speed up and overtake them

- wave your fist at them

- yell abuse at them

- flip them the ‘bird’.

The selection of answer choices for the question makes the assumption that all drivers/riders are aggressive in traffic when someone cuts them off, and only the level of aggression is in question.

- This question does not provide any neutral options.

- This type of leading or loaded question invalidates any results of your research and puts your ethical stance in the spotlight.

Absolute Questions

These are questions that force a respondent to answer Yes or No when there should be at least 3 options.

For example: Do you always drive your car to work? No/Yes.

The word ‘always’, and only having responses of No/Yes to select from creates a far from ideal experience for the respondents, and they may cease to participate.

Recall-Dependent Questions

These types of questions ask respondents to recall (remember) experiences/information from their past that are probably no more than a hazy memory. This can introduce bias into the study.

For example, an employee has been with the company for over 28 years, your question asks them when they became qualified for the machine they operate. You may find they struggle to give you a correct answer, and over or underestimate the date. For this type of question, it would be much easier to obtain the correct answer from employee records.

Another example could be: How much do you spend on wine in a year? Respondents won’t know this. If they purchase their wine from the same outlet each time, they may be able to find out from their bank account statement how much they spent overall at each visit. But if they purchased anything else at the same time, such as a gift, or her alcohol, or non-alcoholic beverages the amount is not going to be accurate.

Answering recall-dependent questions always comes down to the amount of time covering the question, or how long ago it occurred.

Socially Desirable Questions

These questions are worded to elicit socially desirable responses, they make the respondent feel the way they answer needs to be viewed favourably by others.

For example: Do you think older people should be sacked from their jobs? This question would generally receive a majority of ‘No’ answers. Respondents may feel society would not look favourably on them if they thought older people should be sacked even if they are still capable of doing their job.

This question is also written using unclear terms. What is ‘older’?

A better question could be: Do you believe there should be mandatory retirement for workers at age 65? Here an age is specified, it is no longer unclear, and there may be a greater mix of Yes/No answers received.

Double-Negative Questions

Basically, double-negative questions cancel each other out and you end up with a positive.

For example: Do you disagree that vaping should not be permitted in playgrounds? This question implies that vaping should be permitted in playgrounds. Read it very carefully and you can see why, but when it comes down to it, the question is just very badly worded.

Limited Response Options

This happens when questions do not provide an answer choice the respondent requires.

For example: Who buys the groceries in your household?

- you

- Mum

- Dad.

There are only 3 options, what if your husband, boyfriend, girlfriend, significant other, grandparent, Aunt, Uncle, cousin, flatmate, etc buys the groceries, or what if it is a shared activity?

When the researcher has no way to know all the variations of answers possible to a question the question should be open-ended, allowing the respondent to input their own answer.

Overlapping Response Options:

This is an error in question design, or proofreading.

For example: What is your current age group – <20, 21-30, 30-40, 40-50, >50. Which selection do those who are 30 or 40 make, there are two options for each age. What about a person aged 20? The choices are less than 20 or 21 to 30, there is no 20 age group.

To ensure no overlaps or exclusions a better selection of age groups could be:

- 20 or less; 21-30; 31-40; 41-50; over 50.

8.2 Distribution

For online distribution of surveys there are several approaches you can select from. There are companies such as Survey Monkey and Qualtrics, or you can develop your own website, or blog. If you are considering using someone else’s website or using social media you may run into issues as many do not permit survey distribution on their platform, you need to read their requirements carefully prior to attempting to use their platform.

You are going to find some textbooks may recommend emailing surveys to potential respondents, but first you need to obtain their email address. After you obtain the email address you have to find out if the person is willing to undertake the survey. Your approach by email may just end up in the Junk or SPAM folders. Emailed surveys can get lost in the incoming tide to an inbox and may be overlooked.

Traditional ‘old fashioned’ ways of surveying such as posting a physical survey to someone, e.g., the household, may result in the survey being dumped in the bin as junk mail or rubbish. This is quite an expensive way of distributing a survey and generally only works when the person has already agreed to undertake the survey. Telephone surveys are quite restricted now in Australia as to the hours they can be conducted and who can conduct them. There is also a ‘do not call’ register of those who definitely do not want to participate, and the reduction in landline phones is also prohibitive.

The remaining traditional form of survey distribution that is still effective is in person. The researcher(s) or assistant(s) physically attend an area where their target population frequents and can hand the survey to those who agree to participate, or if the survey is interview style ask the questions.

8.3 Interviews

Structured or Standardised Interviews

A structured or standardised interview is on occasion described as a quantitative interview. With this type of interview, the researcher reads each question and the answer options to the respondent, with the researcher marking down the answers. The questions are generally closed. In this instance if the respondent does not understand a question they can ask for clarification.

In a quantitative structured interview, an interview schedule is used. This provides a guide to the researcher as they ask the questions, and selection of answers to the respondent. The researcher must ask each question and provide each answer in the same way for the whole interview, the tone of voice, inflections etc must stay the same to prevent any researcher influence on the answers. This form of data collection can be very labour intensive due to the amount of time it takes for the researcher to ask each question and record each answer; unless there is a team, it is conducted one interview at a time (Sheppard, 2020).

Semi-Structured Interviews

The semi-structured interview is qualitative, it is a more relaxed approach than the quantitative structured interview. There is a mix of both open-ended and closed questions asked, but the interviewer does not have to stop when the respondent first answers, they can seek further information from the respondent. Although more time consuming (up to 1-hour generally) than the structured interview the semi-structured interview is seen as providing more valuable insights into the respondents and their answers. In a semi-structured interview demographic questions are generally left until last as the answers can be viewed by respondents as sensitive, or private, and they may be reluctant to part with the information. A researcher should only ask the absolute necessary demographic questions to ensure the respondent stays relaxed and no harm is caused (Adams, 2015). Themes and key questions rely on the researcher’s philosophical stance.

Unstructured Interviews

An unstructured interview is qualitative, very relaxed and informal, they do not apply to a list of pre-determined questions. The researcher (or interviewer) conducting the unstructured interview needs to be highly skilled and experienced to successfully obtain the information they are seeking from the respondents, and in the respondents’ own voice. This type of interview is generally an extension of research conducted as participant observation, and the researcher/interviewer has, at times, already developed a relationship with the respondent, when this occurs the relationship often continues after the research has ceased (Sanchez, 2014).

Recording Interviews

As with other forms of recording respondent information, there are ethical considerations that need to be applied. See Chapter 1 about ethics.

Key Takeaways

-

There are multiple factors to consider when writing a questionnaire and it requires careful planning.

- Writing a good question is extremely important. You now understand how to write a question so that it is not double-barrelled, unclear, leading or loaded, absolute, recall dependent, socially desirable, double negative, limited response, or containing overlapping responses.

- There is a difference between open-ended and closed questions, and what demographic questions are and why they are useful.

- You understand what a categorical question is, and the differences between semantic differential scales, interval scales, ratio scales, and Likert scales.

- A structured interview is sometimes referred to as a quantitative interview due to its structured nature.

- Themes and key questions for a semi-structured interview depend on the researchers’ philosophical stance.

- An unstructured interview has no predetermined themes or questions.

References

Adams, W. (2015). Conducting semi-structured interviews. In J. Wholey, H. Hatry, & K. Newcomer (Eds.), Handbook of practical program evaluation, (pp. 492-505). Jossey-Bass. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119171386.ch19

Manning, M., & Munro, D. (2007). The survey researcher’s SPSS cookbook (2nd ed.). Pearson Education Australia.

McNabb, D. E. (2021). Research methods for political science: Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed method approaches (3rd ed.). Routledge Taylor and Francis Group.

Sanchez, C. (2014). Unstructured interviews. In A. C. Michalos (Ed.), Encyclopedia of quality of life and wellbeing research, (pp. 6824-6825). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-0753-5_3121

Sheppard, V. (2020). Research methods for the social sciences: An introduction. https://pressbooks.bccampus.ca/jibcresearchmethods