4.3. Attention

By Judith Rafferty, adapted by Marc Chao and Muhamad Alif Bin Ibrahim

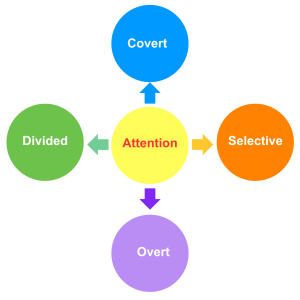

Our perceptions are significantly shaped by what we choose to focus on (Goldstein, 2019). Attention acts as a filter, determining which parts of our environment we prioritise and how we interpret them. By directing our attention to specific stimuli, we amplify their importance in our minds, while other stimuli fade into the background. This process highlights attention as a critical factor in understanding how people perceive and navigate their environments. However, there are different types of attention, each serving unique purposes. Figure 4.3.1 below illustrates the distinctions between various types of attention.

In this section, we will explore selective attention and divided attention in greater detail. We will also examine specific phenomena related to attention and how they influence perception, ultimately shaping people’s experiences.

Selective Attention

Selective attention acts like a filter, allowing us to manage the constant flow of information around us. This process helps us focus on specific inputs for further processing while ignoring others. Heen and Stone (2006) use the example of two individuals, Eric and Fran, who had access to the same pool of information, such as what was said during a work meeting, but each focused on different aspects of that shared information.

The authors describe a phenomenon known as the “user illusion”, which refers to the belief that we perceive everything around us when, in reality, we only take in a small fraction of the available information (p. 344). This selective focus significantly influences how we interpret situations and form conclusions.

In the context of critical thinking, selective attention highlights the importance of being mindful of what we focus on and what we might overlook. The example of Eric and Fran shows how selective attention can shape individual perceptions and influence the narratives we construct about situations. By understanding the filtering nature of attention, we can become more aware of our cognitive biases and work toward a more balanced and comprehensive approach to evaluating information.

Cocktail Party Effect

The cocktail party effect is a fascinating demonstration of selective attention, which is our ability to focus on specific stimuli while filtering out others. Imagine yourself at a lively party: the room buzzes with the chatter of conversations, glasses clinking, music playing in the background, and perhaps the sizzle of food being cooked nearby. Despite all this noise, you can effortlessly concentrate on a conversation with a friend, tuning out the surrounding noise. This ability to selectively focus on one auditory source while ignoring others is what defines the cocktail party effect.

The cocktail party effect hinges on the brain’s ability to process auditory information selectively. While it might seem as though we are ignoring all other sounds, our brains are actually processing these background noises at a lower level. This becomes evident when a stimulus outside our immediate focus grabs our attention. For example, if someone across the room says your name or shouts an alarming word like “Fire!”, your attention will immediately shift to that sound, even though you were not consciously listening for it. This demonstrates the brain’s ability to monitor the environment for meaningful or relevant information while maintaining focus on a primary task.

We rely on selective attention because of our limited cognitive capacity. However, our ability to ignore irrelevant stimuli depends on two factors: the cognitive load of the task we are engaged in and the strength of the task-relevant stimuli. For instance, the Stroop task is a classic example where it becomes challenging to ignore irrelevant stimuli due to the powerful influence of task-relevant information. This interplay of attention and cognitive load reveals how our minds prioritise information in complex environments.

Divided Attention

Divided attention refers to the ability to focus on two or more tasks simultaneously. It occurs when we intentionally split our mental resources to manage multiple activities at once. This ability is essential in many aspects of daily life, allowing us to perform tasks efficiently in environments where competing demands are common.

For example, consider having a conversation while driving. Your attention is divided between processing the road’s visual and spatial information, such as monitoring traffic and steering the vehicle, and interpreting and responding to the conversation. Similarly, listening to music while working involves managing the auditory input of the music alongside focusing on the details of your task.

Divided attention is particularly valuable in situations where multitasking is unavoidable, such as managing household chores, engaging in collaborative work, or navigating social interactions while completing errands. However, the degree to which we can successfully divide our attention depends on the complexity of the tasks and the cognitive resources required for each.

While divided attention can seem like a superpower, it comes with significant limitations. Our brain’s capacity to process information is finite, meaning that the more tasks we attempt to manage simultaneously, the more likely we are to experience cognitive overload. This can lead to decreased accuracy, slower reaction times, and poorer performance on all tasks involved.

The extent to which divided attention is successful depends on:

- Task complexity: Simpler tasks that are routine or automatic, like folding laundry, are easier to combine with other activities. However, when both tasks require higher levels of focus, such as solving a complex problem while participating in a meeting, performance on one or both tasks will likely suffer.

- Cognitive resources: Some individuals are better at multitasking than others due to differences in cognitive capacity and working memory. However, even those with strong cognitive skills experience limitations when juggling demanding tasks.

It is worth noting that what we often call multitasking is, in many cases, attention switching rather than true divided attention. Instead of processing multiple tasks simultaneously, our brain rapidly alternates focus between tasks. For example, when you check your phone while working on a report, your brain is switching back and forth between the two activities. Each switch requires cognitive effort, and this can create a loss of efficiency known as the switching cost.

Divided attention may be an important skill in today’s fast-paced, multitasking world, but it has consequences for our ability to process information effectively. For instance, attempting to multitask during activities that require high levels of focus, such as driving, can increase the likelihood of errors or accidents. Studies have shown that distracted driving, where attention is divided between the road and another task, such as texting, significantly impairs reaction times and decision-making.

Even in less critical scenarios, dividing attention can impact memory retention and the quality of work. For example, listening to a podcast while studying may lead to poor recall of the study material because your brain is splitting its resources between absorbing the audio content and processing the study information.

Inattentional Blindness

Attention is a cornerstone of perception. Without it, we cannot fully process or make sense of the stimuli around us. It allows us to filter the overwhelming amount of sensory information we encounter and focus on what we deem important. However, this focus comes at a cost, as demonstrated by the phenomenon known as inattentional blindness.

Inattentional blindness occurs when we fail to notice a visible and seemingly obvious stimulus because our attention is focused on something else. This phenomenon highlights the limitations of our perceptual systems: while attention helps us concentrate on specific tasks or objects, it also causes us to overlook other, potentially significant details in our environment.

A classic example of inattentional blindness is the experiment conducted by Daniel Simons and Christopher Chabris (1999). If you have not already, take a moment to watch the video below [1:21].

In this study, participants were asked to watch a video of people passing a basketball and count how many times players wearing white shirts passed the ball. During the video, a person dressed in a gorilla costume walks through the scene, stops, and even pounds their chest before leaving. Astonishingly, nearly 50% of participants failed to notice the gorilla, even though it was in plain sight.

Inattentional blindness happens because attention is a limited resource. When we direct our focus toward one task, such as counting basketball passes, our brain filters out other information that it deems irrelevant to the task at hand. This filtering mechanism is crucial for managing cognitive overload, but it also means that highly visible stimuli, like the gorilla, can go unnoticed if they fall outside our focus.

This phenomenon illustrates the trade-off in attention: by concentrating on what we believe is important, we lose awareness of other elements in our environment. While this mechanism helps us manage tasks efficiently, it can also cause us to miss critical details.

Inattentional blindness has real-world implications for how we understand perception and attention. It demonstrates that what we perceive is not a complete or objective representation of reality but rather a filtered version based on what we focus on. This insight is critical for understanding human behaviour, decision-making, and even safety.

For example:

- In driving, inattentional blindness can lead to accidents if a driver focuses on a GPS screen or a phone and fails to notice a pedestrian crossing the road.

- In medical settings, inattentional blindness may cause a radiologist to miss an abnormality in a scan if their attention is focused elsewhere.

The Simons and Chabris experiment powerfully illustrates how attention shapes perception. It reveals that perception is not simply a passive process of taking in everything around us but an active one, where attention determines what gets processed and what gets ignored. Understanding inattentional blindness helps us appreciate the limitations of our attention and encourages us to be more mindful of where we direct it. By recognising these limitations, we can strive to broaden our focus when necessary and remain open to noticing details that might otherwise go unnoticed.

References

Goldstein, E. B. (2019). Cognitive psychology. Cengage.

Heen, S., & Stone, D. (2006). Perceptions and stories. In A. Kupfer Schneider & C. Honeyman (Eds.), The negotiator’s fieldbook: The desk reference for the experienced negotiator (pp. 343-350). American Bar Association.

Chapter Attribution

Content adapted, with editorial changes, from:

Neuroscience, psychology and conflict management (2024) by Judith Rafferty, James Cook University, is used under a CC BY-NC licence.