4.5. Beliefs

By Michael Ireland, adapted by Marc Chao and Muhamad Alif Bin Ibrahim

A belief is simply the acceptance of something as true. It reflects a personal stance we take toward a claim, where we regard it as accurate or factual. Beliefs are connected to propositions, which are statements that can be either true or false, and a concept we have encountered multiple times in Chapter 2. When someone accepts a proposition as true, they are said to hold a belief in it.

Beliefs can encompass a wide range of ideas. They may involve interpretations of events, evaluations of situations, conclusions drawn from evidence, or predictions about the future. Importantly, beliefs do not exist in isolation. Instead, they tend to form interconnected systems, often referred to as belief systems or working models. These systems consist of clusters of beliefs that support and influence one another, helping us make sense of the world.

Belief models serve as frameworks we rely on to interpret experiences, navigate life, and make decisions. By understanding beliefs and their connections within these systems, we can better appreciate how they shape our perspectives and guide our actions.

Beliefs and Models

How do we navigate and interact with the world? When we wake in the morning and our brains begin processing the flood of electrical and chemical signals from our eyes, ears, and body, how do we make sense of it all? How do we know what to do next? Despite our inability to predict the future, we are not paralysed by indecision or overwhelmed by uncertainty. The answer lies in how our brains manage this complexity: through mental representations or working models of the world. Understanding how these models function helps us recognise both their strengths and vulnerabilities.

What Are Mental Models?

Mental models are like internal maps that we rely on to interpret the world. They help us understand who we are, the resources available to us, and how we should navigate our surroundings. These models are built from past experiences and beliefs, and they allow us to grasp the essential features of the world, anticipate events, and forecast the consequences of our actions. In essence, mental models are tools we use to organise our beliefs, process information, and make decisions.

An important insight is that we do not interact directly with the world; instead, our experiences are filtered through these models. This means we live more “inside our heads” than we might realise. Our understanding of the past, our decisions in the present, and our expectations for the future are all shaped by these models, which act as lenses to filter and shape our perceptions.

Lenses: Focus and Distortion

Like physical lenses, mental models focus our perception but also distort it. This distortion is not inherently bad; it is what makes lenses useful. They simplify the overwhelming complexity of reality, allowing us to focus on specific aspects that are most relevant. However, these distortions also introduce biases and prejudices, which can lead to misunderstandings or flawed judgements. Recognising the benefits and limitations of these lenses is crucial for navigating the world effectively.

What Is a Model?

The term model refers to an abstract representation that highlights key features of something while ignoring less relevant details. For instance, a model plane represents aspects of a real plane, such as its shape, dimensions, and colour, while excluding intricate details like its engine components or the exact number of bolts. Similarly, cognitive models simplify reality, using past experiences and knowledge to create representations of the world that help us make predictions and decisions.

Consider the photograph of a train model in Figure 4.5.1. The image captures important features of the train, but many details are left out. This is the essence of a model: it is not the real thing but a simplified and idealised version designed to highlight what is most important.

One key assumption underlying mental models is that the future will resemble the past. This assumption works well most of the time, but can occasionally lead to errors. The greatest strength of mental models, which is their ability to simplify reality, is also their biggest weakness: they are always incomplete and partial. When we rigidly cling to these models, we risk misunderstanding new information or failing to adapt to changing circumstances.

Flexibility is critical. By revising our models based on new experiences and information, we can refine and improve our understanding of the world. Over time, a well-maintained model becomes increasingly sophisticated and effective at predicting events and guiding our behaviour.

Mental models prioritise practical utility over accuracy. This means they evolve to help us survive and succeed rather than to perfectly represent reality. For instance, certain beliefs, such as superstitions, persist because they serve a purpose, even if they are not entirely accurate. Philosophers have explored this idea extensively, with discussions on “false but useful beliefs” highlighting how certain models, though flawed, can still be beneficial.

By filtering out unnecessary details and noise, models allow us to focus on what is most relevant. For example, a clinical psychologist might use diagnostic criteria as models to identify mental illnesses. While these models are helpful, they do not perfectly capture the complexity of individual cases. Similarly, in the fashion industry, a model is used to idealise how clothing might look, even if it does not perfectly represent reality.

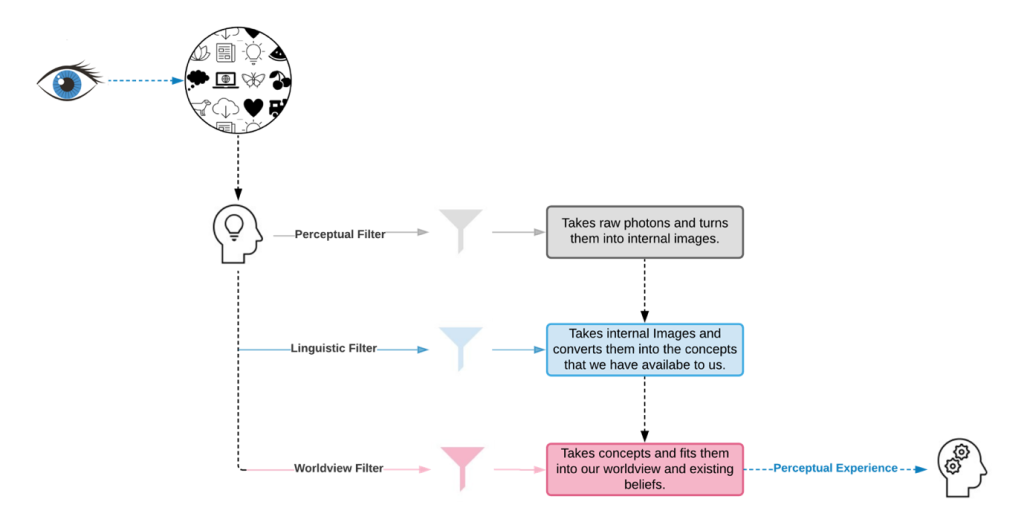

Our mental models pass raw sensory information through multiple filters before any perception takes place. These filters, such as prior knowledge, biases, and cultural influences, shape how we interpret the world. Figure 4.5.2 illustrates an example of these filters.

Beliefs and Sensation: A Chicken-and-Egg Problem

The relationship between beliefs and sensation is a dynamic and intricate interaction that defies simple explanations. Many people assume that our beliefs about the world arise solely from raw sensory experiences. However, this perspective oversimplifies the process. Our beliefs not only shape the way we interpret sensory input, but they also act as filters, determining what we sense in the first place. In fact, some beliefs, such as those about abstract concepts like infinity, exist independently of sensory experiences, further illustrating the complexity of this interaction.

How Beliefs Shape Sensation

A classic study by Harvard psychologists Jerome Bruner and Leo Postman (1949) provides a compelling demonstration of how beliefs influence sensory perception. Participants were shown a series of playing cards, some of which were intentionally altered to include anomalies (e.g., a red four of spades, even though spades are always black). When these anomalous cards were briefly displayed, participants often misidentified them as normal cards, confidently reporting what they believed to be “correct”. For example, a black six of hearts might be mistaken for a six of spades because participants’ existing belief systems filtered the information to fit what they expected to see.

This study illustrates how deeply our beliefs act as lenses or filters, shaping what we perceive and how we make sense of our experiences. Rather than perceiving the world as it truly is, we often see a version of reality that aligns with our pre-existing beliefs.

This interaction creates a feedback loop. Our beliefs influence how we perceive the world, and in turn, our perceptions reinforce our beliefs. Numerous studies confirm that strong belief systems can lead individuals to suppress or dismiss contradictory information. Additionally, our sensory experiences are inherently ambiguous and rely on top-down processing, where the brain uses prior knowledge and expectations to interpret sensory input. This ambiguity makes us susceptible to confirmation bias, a cognitive tendency to favour information that supports our existing beliefs while ignoring or rejecting evidence that contradicts them.

However, ambiguity is not solely a liability. It can also foster creativity and serve as a counterbalance to dogmatism. Embracing ambiguity can open the door to new ways of thinking, encouraging flexibility and curiosity rather than rigid adherence to preconceptions.

Different Belief Systems, Different Worlds

The historian of science Thomas Kuhn, in his seminal work The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962), argued that individuals with different worldviews, or paradigms, effectively inhabit different worlds. Kuhn suggested that people with contrasting belief systems might perceive the same scene in entirely different ways. For example, two individuals with divergent worldviews may interpret the same event, image, or piece of data in fundamentally different ways.

Kuhn went even further to assert that individuals with opposing paradigms might struggle to communicate effectively because they interpret words, concepts, and experiences differently. From their subjective perspectives, it might genuinely seem as though they are living in entirely separate realities.

Although Kuhn’s view is extreme, it underscores an essential point: our worldviews significantly shape how we experience and interpret the world. Understanding this can help us navigate conversations and interactions with individuals from different cultures, religions, or political backgrounds, whose worldviews may differ radically from our own.

Our beliefs are not just abstract ideas; they are intimately tied to our sense of self and identity. This is why challenges to our core beliefs can feel deeply unsettling, even threatening. Losing faith in a cherished worldview can be as psychologically devastating as losing religious faith. Beliefs serve as the building blocks of our worldview, and when these are questioned or dismantled, it can feel as though the very foundation of our identity is at stake.

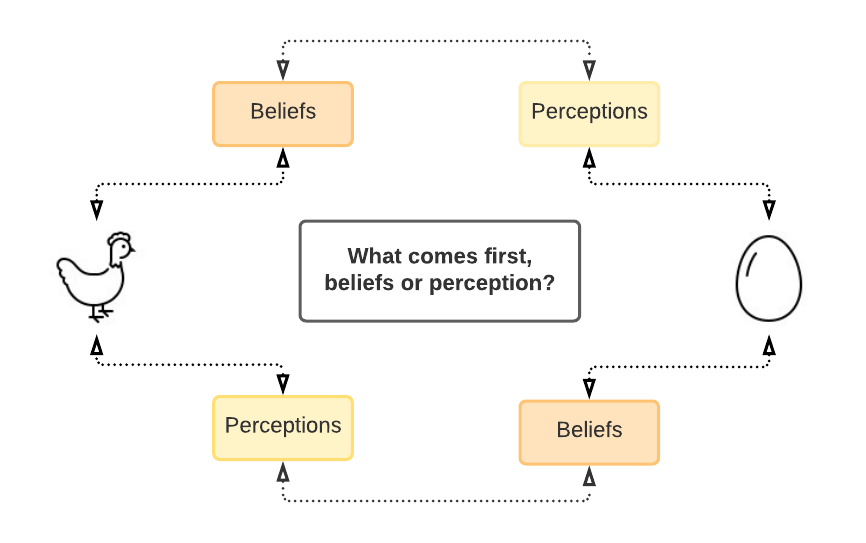

A Circular Dynamic

This relationship between beliefs and sensation is akin to a chicken-and-egg problem: beliefs shape our perceptions, and perceptions, in turn, reinforce our beliefs. As shown in Figure 4.5.3, this dynamic creates a self-reinforcing system in which we interpret the world through the lens of our pre-existing worldview. This process makes us resistant to perceptions or experiences that might challenge our beliefs, a significant liability in critical thinking.

To overcome this tendency, we must consciously work to question and revise our beliefs when faced with new evidence. Being a skilled thinker means adopting an open-minded attitude toward our beliefs and recognising the filters that shape our perceptions. This awareness can help us avoid the pitfalls of confirmation bias, where we seek out and interpret information in ways that confirm our pre-existing beliefs.

Francis Bacon (1561–1626) eloquently articulated the dangers of confirmation bias centuries ago:

The human understanding, when it has once adopted an opinion, draws all things else to support and agree with it. And though there be a greater number and weight of instances to be found on the other side, yet these it either neglects and despises, or else by some distinction sets aside and rejects; in order that by this great and pernicious predetermination the authority of its former conclusions may remain inviolate.

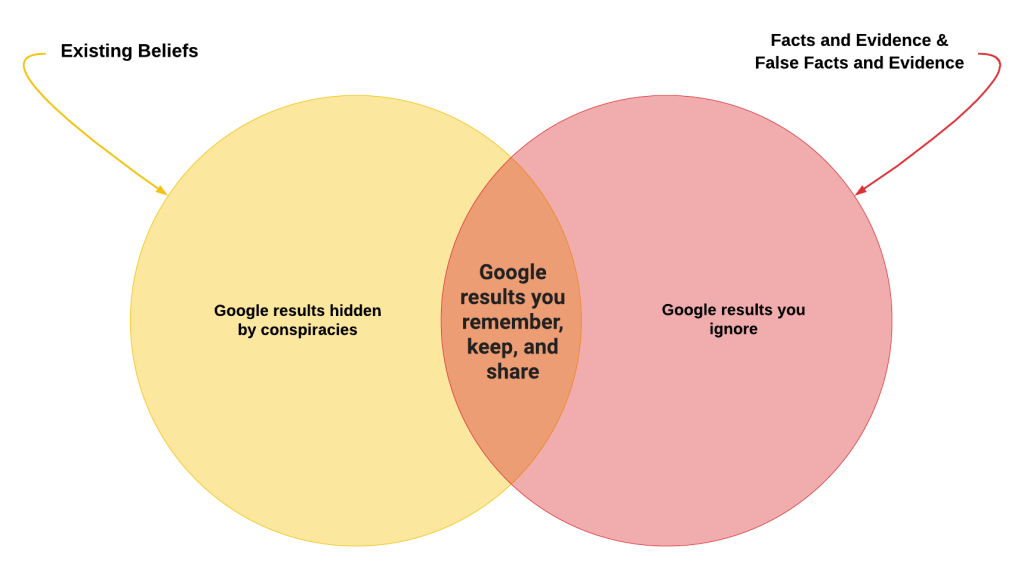

Bacon’s insight remains highly relevant today. It reminds us that our natural tendency is to protect and reinforce our beliefs, even in the face of conflicting evidence (Figure 4.5.4). Recognising this bias is the first step toward developing a more flexible and critical approach to our thinking, one that allows us to adapt and grow as we encounter new information and perspectives.

Structure of Belief Systems

Beliefs rarely exist in isolation. Instead, they are part of integrated and interdependent systems, which are networks or webs of beliefs that support and reinforce one another. By “integrated”, we mean that these beliefs generally fit together in a cohesive way; people tend to resist holding contradictory beliefs. By “interdependent”, we mean that the credibility of any single belief often relies on the truth of numerous other beliefs within the system. This interconnected nature of beliefs is described as holistic, an important concept developed by logician Willard Van Orman Quine.

What Is Holism?

In its original sense, holism refers to systems in which individual parts cannot be fully understood in isolation but must be considered as part of the whole. For example, in holistic medicine, the focus is not just on treating the symptoms of a disease but on understanding and addressing the physical, mental, and social factors that contribute to a person’s overall health.

When applied to beliefs, holism means that each belief is connected to others in a larger system. This network of interconnected beliefs forms a web (a metaphor introduced by Quine). Beliefs at the core of this web are those most central to our worldview. These are beliefs we are deeply committed to and that are heavily fortified against change. Meanwhile, beliefs on the periphery of the web are less critical and can be more easily modified or discarded without threatening the integrity of the entire system.

The Web of Beliefs

The web structure of beliefs explains why changing someone’s deeply held views can be so difficult. Core beliefs are intertwined with many others, forming the foundation of a person’s worldview. If a core belief is challenged or disproven, it often triggers a chain reaction that destabilises related beliefs. For this reason, we tend to protect core beliefs, even when presented with evidence that contradicts them.

For example, if someone holds the belief that the Earth is 6,000 years old (a view common among some fundamentalist religious groups), that belief implies a host of others:

- The fossil record must be flawed or misinterpreted.

- Evolution cannot be true.

- Humans and dinosaurs must have coexisted.

These interconnected beliefs create a system where challenging one belief requires addressing the entire network. The person may not even be consciously aware of all the auxiliary beliefs tied to their core worldview until they are confronted with specific challenges.

Quine’s web metaphor helps illustrate how we protect our core beliefs. Surrounding the core is a “protective belt” of auxiliary beliefs that can be adjusted or sacrificed to defend the core. When faced with conflicting evidence, people are more likely to abandon peripheral beliefs rather than reconsider those at the centre of their worldview.

For instance, if someone believes the moon landing was faked and is shown satellite images of footprints on the moon, they face a choice:

- Revise the core belief about the faked moon landing, or

- Abandon a peripheral belief, such as trust in the accuracy of satellite imagery.

In this scenario, they might choose the second option, dismissing satellite imagery as unreliable, even if they had no reason to doubt it before. By doing so, they protect their core belief, reinforcing their worldview despite the evidence against it. This strategy highlights how we can use an almost infinite number of “moves” to shield deeply held beliefs from revision.

The Emotional Investment in Core Beliefs

Core beliefs are often cherished because they are central to our identity and worldview. Changing these beliefs can feel deeply destabilising or even traumatic. In many cases, these beliefs take on the role of sacred cows, which are ideas we refuse to abandon, even when confronted with overwhelming evidence. Confirmation bias, the tendency to favour information that supports our existing beliefs while dismissing contrary evidence, is one of many psychological tools we use to protect these sacred cows.

Imagine someone who believes the moon landing was faked. This belief might be tied to a broader worldview about government corruption and deceit. When presented with strong evidence, such as images of lunar footprints, they could choose to revise their belief about the moon landing. However, they are more likely to adjust a peripheral belief, such as doubting the reliability of satellite imagery. This allows them to maintain their core belief without disrupting their broader worldview.

Understanding the structure of belief systems highlights why it is so difficult to change deeply held views, whether in ourselves or others. It also shows how people can cling to beliefs despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary, using the web-like nature of their belief systems to defend and reinforce their worldview.

Developing the Right Attitudes Toward Beliefs

With our understanding of how beliefs are formed, structured, and protected, we should now feel motivated to avoid the common pitfalls that our beliefs can lead us into. To do this effectively, we need to adopt a thoughtful and intentional stance toward our beliefs.

Much like the critical thinking dispositions we discussed earlier, this is not an exhaustive list but rather an overview of some helpful approaches to relate to our beliefs in a healthier and more constructive way. These attitudes can guide us in navigating the complexities of belief systems while remaining open to growth and self-reflection.

Modesty

The first essential attitude we need to cultivate is modesty toward our beliefs. After exploring this chapter, several key points should now be clear:

- We do not know nearly as much as we think we do.

- Our beliefs are built on sensory and perceptual foundations that are much shakier than we often realise.

- Our contact with the outside world is indirect, filtered, and augmented.

- We sometimes unconsciously use devious tactics to protect beliefs we are emotionally attached to.

- We can be, and likely are, wrong about many of the beliefs we currently hold.

Despite these realities, most of us lack modesty when it comes to our beliefs, and this overconfidence often leads to trouble. Philosopher Willard Van Orman Quine, borrowing a Biblical expression, famously noted that the desire to always be correct is a “pride that goes before destruction”, which is a mindset that prevents us from recognising our mistakes and hinders the advancement of knowledge.

Holding Beliefs Lightly

We should approach all our beliefs as provisional, meaning they are rough estimations that have yet to be falsified. Our access to information is always partial and potentially biased, often influenced by someone else’s agenda. Therefore, we have no right to absolute certainty about our beliefs.

Unfortunately, much like an insecure lover, many of us feel an overwhelming need for certainty in our beliefs. Without strong critical thinking skills, we find uncertainty intolerable and often cling to bad information, even knowingly, just to avoid the discomfort of not knowing.

Adopting a modest attitude toward our beliefs allows us to:

- Be open to the possibility of being wrong.

- Reduce the impact of confirmation bias, which causes us to seek out and favour information that supports our existing beliefs.

- Foster a more tolerant mindset toward conflicting ideas, as certainty often fuels intolerance.

Certainty can be dangerous, as it often closes us off to alternative perspectives and stifles progress. History shows us that those most certain of their own ideas tend to be the least tolerant of others. By embracing modesty, we create space for growth, learning, and the development of more accurate and inclusive understanding, both individually and collectively.

Falsifiability and Intellectual Courage

Let us revisit two critical points. First, we must always remember that our beliefs are merely our best guesses and are approximations of reality rather than absolute truths. Second, confirming evidence for almost anything is both easy to find and often misleading. In fact, confirming evidence often misses the point entirely. In science, the most valuable evidence is that which emerges from attempts to falsify a proposition and fails to do so. This principle applies not only to scientific theories but also to our everyday beliefs and perceptions.

Confirming evidence, though often comforting, is not the most reliable way to support a belief. This is because it fails to establish whether the belief could withstand serious scrutiny or opposing evidence. Logically speaking, only disconfirming evidence has the proper relationship with propositions, as it directly challenges their validity.

The tendency to rely on confirming evidence is tied to confirmation bias, our natural inclination to seek out information that supports what we already believe while ignoring contradictory evidence. This bias makes it all the more important to emphasise falsifiability, which is the practice of actively seeking evidence that could disprove a belief or claim.

Understanding Falsification

Falsification is a method of approaching evidence by focusing on its ability to contradict ideas or claims. Instead of gathering evidence that supports a proposition, falsification prioritises efforts to disprove it. This concept was popularised by philosopher Karl Popper in his book The Logic of Scientific Discovery (1934), where he argued that the true test of a theory is the ability to attempt to prove it wrong.

Popper viewed confirmation as a flawed approach, riddled with both psychological and logical issues. For instance:

- We are naturally skilled at finding evidence that supports our views, often without realising how selective or biased this process can be.

- Disproving a claim is usually much simpler and more conclusive than trying to confirm it.

Take the claim “All swans are white”. To confirm this, we would need to observe millions of swans, and even then, we could not be certain we have seen them all. However, falsifying the claim requires only a single observation of a black swan. The discovery of even one black swan immediately disproves the proposition. This demonstrates the power of falsifying evidence compared to the often inconclusive nature of confirming evidence.

The Role of Scepticism

To think critically, we must approach our beliefs with scepticism. This means not taking confirming evidence at face value and being mindful of the emotional and psychological attachments we often have to certain beliefs. Our tendency to protect cherished beliefs from falsification can cloud our judgement, making it harder to recognise when we are wrong.

If we truly value truth, we need the intellectual courage to actively seek out disconfirming evidence, even if it challenges beliefs we hold dear. This requires vigilance and resilience, as having deeply held views falsified can be unsettling or even devastating. Yet, the pursuit of truth demands this level of boldness and integrity.

As the philosopher Immanuel Kant famously stated, “If the truth shall kill them, let them die.” Here, we can interpret “them” as referring to our beliefs, assumptions, or ideas. If a belief cannot withstand scrutiny, it deserves to be abandoned in favour of a more accurate understanding.

The opposite of this courageous stance is intellectual laziness or timidity. Fearing the discomfort of being wrong, we may avoid testing our beliefs or confronting disconfirming evidence. This avoidance undermines our ability to grow and learn, leaving us clinging to false or incomplete understandings of the world.

By contrast, intellectual courage means being bold enough to question and challenge even our most cherished beliefs. This willingness to sacrifice outdated or incorrect ideas can lead to a deeper, more accurate understanding of reality, and, in some cases, might even save your life.

Openness and Emotional Distance

To become effective critical thinkers, we must cultivate openness toward the limitations of our perceptual and belief systems. This means being willing to accept that we could be wrong about what we sense, perceive, or believe. It also involves recognising the biases we use to shield our beliefs from falsification, actively seeking out evidence that challenges our ideas, and remaining open to change when new information arises.

Being open to opposing ideas is not just a hallmark of intellectual maturity, it is also fundamental to critical thinking. When we lack openness, we tend to oversimplify or misrepresent views that differ from our own. For instance, in cultural or political debates, the right often caricatures the left, and vice versa, each side creating comforting but distorted fictions about the other. This resistance to nuance stifles understanding and meaningful dialogue.

Emotional Distance

Emotional distance from our beliefs is equally important. When we tie our sense of identity or self-worth too closely to our beliefs, it becomes much harder to accept that those beliefs could be wrong. This emotional attachment fosters resistance to new information, especially if that information contradicts deeply held ideas.

No one enjoys being wrong or discovering that something they believed is false. However, by practising emotional detachment, we can reduce the discomfort of these moments. Actively seeking to falsify our own beliefs helps us identify and discard incorrect ideas, and cultivating emotional distance makes this process less painful.

By maintaining a healthy detachment, we can approach even our core beliefs with a willingness to question and revise them. This openness not only strengthens our ability to think critically but also ensures that we remain flexible and adaptive in the face of new evidence or perspectives.

Chapter Attribution

Content adapted, with editorial changes, from:

Mastering thinking: Reasoning, psychology, and scientific methods (2024) by Michael Ireland, University of Southern Queensland, is used under a CC BY-SA licence.