3.4. Fallacies of Irrelevance

By Michael Ireland, adapted by Marc Chao and Muhamad Alif Bin Ibrahim

Fallacies of irrelevance differ from fallacies of insufficiency in a fundamental way. While insufficient reasoning arises when an argument lacks key evidence or supporting details, the premises at least attempt to address the claim directly. In contrast, irrelevant reasons introduce premises that have no meaningful connection to the claim being made, effectively shifting the focus away from the central argument rather than supporting it.

The core issue with fallacies of irrelevance is that they distract attention from the original claim by introducing unrelated information. This distraction can derail meaningful discussion and prevent proper evaluation of the argument. Determining whether a premise is relevant or irrelevant depends entirely on the specific claim under discussion, meaning relevance must always be evaluated on a case-by-case basis.

For instance, it would be fallacious to dismiss vegetarianism simply because an infamous historical figure like Hitler was a vegetarian. In this example, the premise (Hitler’s dietary choices) has no bearing on the ethical or health arguments for vegetarianism. The historical association serves as an emotional distraction rather than addressing the merits of the claim itself.

However, it would not be fallacious to criticise Hitler’s human rights policies based on his history of cruelty and moral failure. In this context, the premise (Hitler’s actions) is directly relevant to evaluating his policies because it provides contextual and moral insight into their implications.

One specific example of this type of fallacy is so frequent and recognisable that it has been given a name: “Reductio ad Hitlerum”. Sometimes humorously referred to as “playing the Nazi card”, this fallacy occurs when someone dismisses or discredits an idea solely because an infamous or disliked figure once held a similar view. Instead of engaging with the actual merits of the argument, the discussion is diverted to an irrelevant association, rendering the reasoning unproductive and logically flawed.

Argumentum ad Hominem (Against the Person)

The ad hominem fallacy occurs when someone attempts to dismiss or undermine an argument by attacking the person making the argument rather than addressing the argument itself. The term ad hominem translates from Latin as “against the man”, emphasising its focus on the individual’s character, motives, or personal traits instead of engaging with the reasoning or evidence they present.

This fallacy arises when someone tries to discredit a claim by targeting the person delivering it, rather than evaluating the quality of the reasons or evidence supporting or opposing it. This tactic is often used to create prejudice against an opponent and divert attention away from the substance of the argument. Ad hominem attacks are particularly common in political debates, where discussions frequently devolve into personal insults and character attacks instead of a reasoned analysis of the actual issues at hand.

A common misconception is that any criticism of a person’s character automatically constitutes an ad hominem fallacy. However, this is not accurate. The fallacy specifically occurs when an attack on character is used to undermine an opponent’s argument, rather than addressing the content of their reasoning or evidence.

For example, someone might say, “You shouldn’t trust John’s opinion on climate change because he failed science in high school.” In this case, John’s academic history has no bearing on whether his argument about climate change is valid or well-supported. The criticism is irrelevant to the claim being discussed.

However, there are situations where character-based criticism might be relevant and not fallacious. If the argument specifically concerns a person’s integrity, behaviour, or credibility, such as in a fraud investigation or an election campaign, then discussing a person’s character may legitimately contribute to the argument.

The core issue with ad hominem attacks is that the character of the person presenting an argument does not determine whether the argument itself is valid or true. For instance, it does not matter whether it was Hitler or Stalin who said that 2 + 2 = 4, the truth of the mathematical statement remains unchanged by their character or moral failings.

In short, valid arguments must stand on their own merits, regardless of who presents them. Personal attacks are irrelevant to the truth or falsity of a claim.

When encountering an ad hominem fallacy, it is important to stay focused on the argument itself. Redirect the discussion back to the premises and evidence supporting the claim, and point out that attacking the person does not address the reasoning or evidence behind their argument. It is also helpful to distinguish between legitimate character-based concerns, such as when credibility is directly relevant to the topic, and irrelevant personal attacks that serve only to distract from the issue at hand.

The ad hominem fallacy undermines meaningful discussions by shifting focus away from what is being said to who is saying it. Effective critical thinking requires evaluating arguments based on their content, evidence, and logical structure, rather than being swayed by personal attacks or irrelevant details about the individual presenting the claim. By recognising and addressing this fallacy, discussions can remain focused, productive, and rooted in reason rather than emotional or prejudicial distractions.

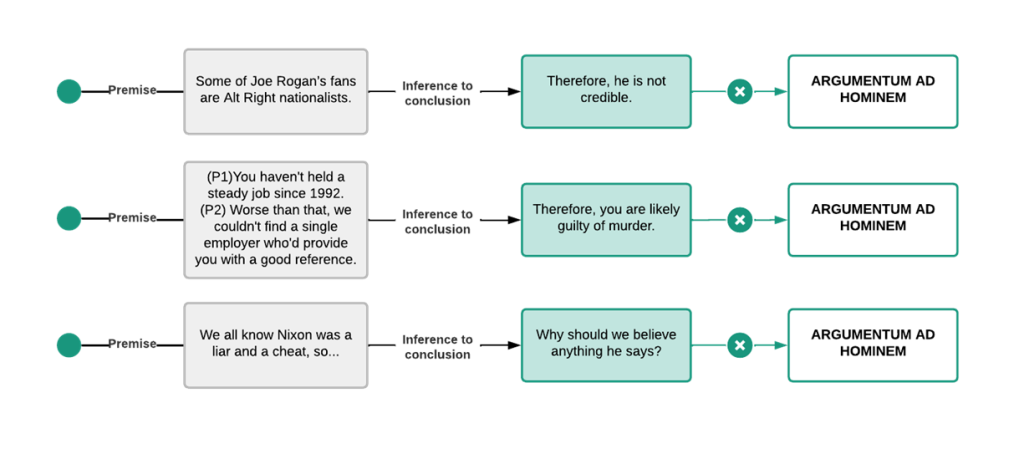

Figure 3.4.1 shows a few more examples of the ad hominem fallacy:

Red Herring

The red herring fallacy occurs when someone introduces an unrelated topic or irrelevant information into a discussion to distract from the original issue. The term originates from hunting, where a strongly scented fish was supposedly used to mislead hunting dogs and divert them from their intended trail. In arguments, a red herring serves a similar purpose, as it shifts attention away from the core claim or question and redirects it to something tangential or unrelated.

This fallacy is a classic example of irrelevance because it deliberately sidesteps the central argument rather than engaging with it directly. By shifting focus to a tangential topic, the person using the red herring avoids having to confront the claims, evidence, or reasoning being presented. This tactic is particularly common when someone cannot effectively counter an argument and instead changes the subject to avoid admitting weakness or conceding a point.

For example, someone might say, “We shouldn’t worry about climate change because there are so many homeless people who need our help first.” While homelessness is undeniably an important issue, it is not directly relevant to the discussion about climate change. The shift in focus serves as a distraction, preventing meaningful engagement with the original argument about climate change.

Another variation of the red herring fallacy often involves ad hominem attacks, where the focus is diverted to someone’s character or personal traits instead of their reasoning. When the accused party starts defending themselves, the original argument gets lost entirely, allowing the person who introduced the red herring to evade addressing the central claim.

The red herring fallacy is known by several other names, including “befogging the issue”, “diversion”, “ignoratio elenchi” (a Latin term meaning ignorance of refutation), “ignoring the issue”, “irrelevant conclusion”, and “irrelevant thesis”. Despite the different labels, they all describe the same fundamental tactic: diverting attention away from the argument to avoid addressing its reasoning or evidence.

Red herrings are particularly deceptive because they disrupt the logical flow of a discussion and prevent meaningful engagement with the core argument. Instead of advancing the conversation, they rely on misdirection and distraction, leaving the original issue unresolved.

Identifying and addressing a red herring requires focus and clarity. It is essential to stay anchored to the original topic and consistently guide the discussion back to the main issue. Politely pointing out the diversion can help refocus the conversation, while asking direct, specific questions about the original claim can prevent further attempts to derail the argument.

The red herring fallacy remains a common and effective rhetorical tactic, often seen in political debates, media discussions, and heated online exchanges. Its power lies in its ability to shift attention away from challenging questions or uncomfortable evidence. Recognising when this fallacy is being used, and skilfully redirecting the conversation back to the central argument, is essential for maintaining clarity, focus, and logical consistency in any meaningful discussion.

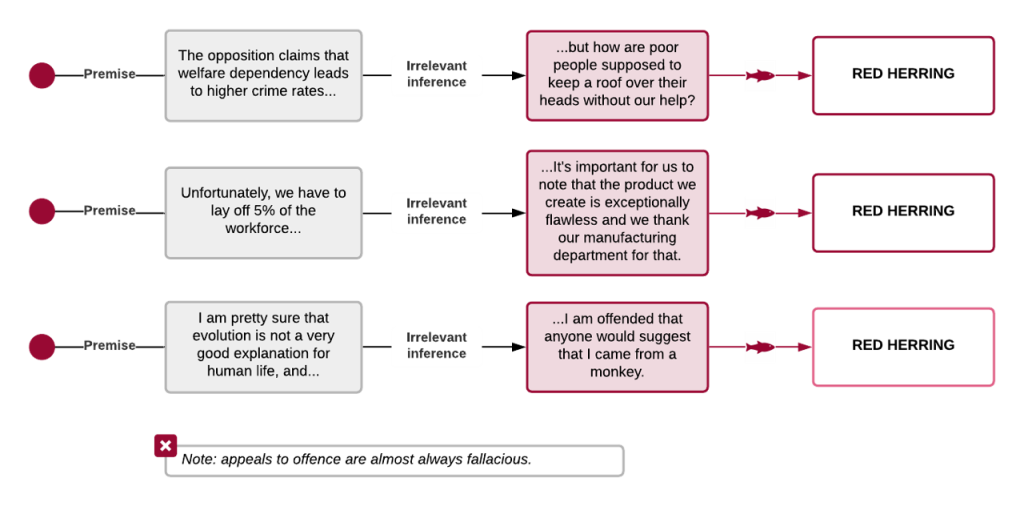

Figure 3.4.2 shows a few more examples of the red herring fallacy:

Tu Quoque Fallacy (“You Too”)

The tu quoque fallacy, which translates from Latin as “you too”, occurs when someone attempts to dismiss an argument by accusing the person making it of hypocrisy. Instead of addressing the claim or evidence, this fallacy shifts the focus onto the behaviour or character of the speaker, implying that their inconsistency invalidates their argument.

This tactic serves as both a form of ad hominem attack and a red herring, as it diverts attention away from the validity of the argument itself and redirects it toward the arguer’s perceived inconsistency. The underlying assumption is that if someone does not “practice what they preach”, their argument must be flawed. However, the truth or falsity of an argument is entirely independent of the person presenting it. Valid arguments rely on evidence and logical reasoning, not the personal behaviour of those who advocate for them.

For example, someone might say, “Doctor, why should I listen to your advice about quitting smoking when you’re a smoker yourself?” While the doctor’s smoking habit might seem like a reason to dismiss their advice, it has no bearing on the validity of the health information they are providing. The fact remains that smoking is harmful to health, regardless of whether the doctor follows their own advice.

The central issue with this fallacy is that it confuses the credibility of the speaker with the merit of their argument. While hypocrisy can undermine trust in a speaker, it does not inherently invalidate the evidence or reasoning they present. Sound arguments must always be judged on their own merits, not on whether the speaker personally adheres to the conclusions they advocate.

When encountering a tu quoque fallacy, it is essential to refocus the discussion on the argument itself. Politely point out that the truth of the claim stands independently of the speaker’s actions or behaviour. Additionally, it can help to acknowledge the distraction directly, noting that accusations of hypocrisy, while perhaps worth discussing in a separate context, do not address the validity of the argument at hand. Finally, return to the core issue by evaluating the reasoning and evidence presented, rather than focusing on the behaviour or perceived inconsistency of the speaker.

The tu quoque fallacy undermines productive discussion by conflating personal behaviour with the validity of an argument. While hypocrisy can justifiably raise questions about a person’s integrity or credibility, it does not automatically render their claims false. Effective reasoning requires us to separate the speaker from the argument and evaluate claims based on evidence, logic, and sound reasoning, rather than on whether the advocate perfectly embodies their own advice. Recognising and addressing this fallacy ensures that discussions remain focused, logical, and productive.

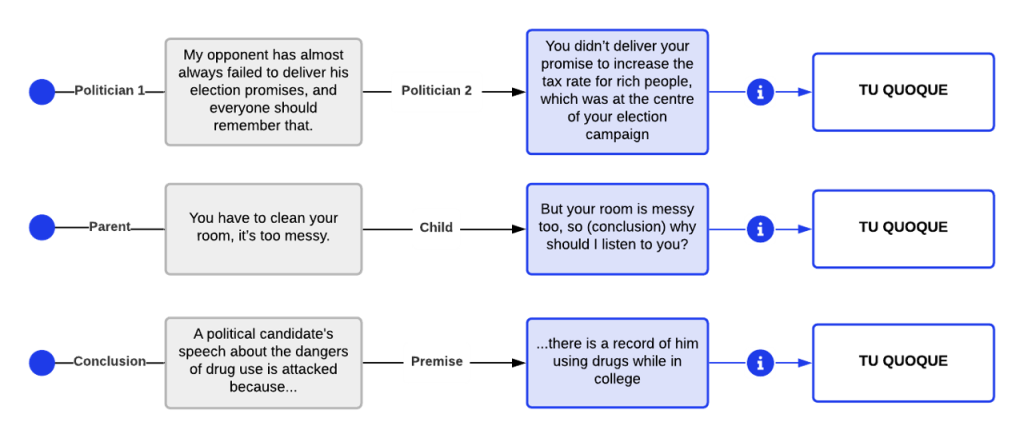

Figure 3.4.3 shows a few more examples of the tu quoque fallacy:

Straw Man Fallacy

The straw man fallacy occurs when someone misrepresents, oversimplifies, or exaggerates an opponent’s argument to make it easier to refute. The metaphor captures this perfectly: defeating a straw man, which is a flimsy, artificially constructed version of an argument, is far easier than confronting a robust, well-supported position.

This tactic is often employed when a debater lacks sufficient reasons or evidence to directly counter their opponent’s actual claims. Instead of addressing the original argument on its merits, they distort or caricature it, then proceed to dismantle this weaker, misrepresented version.

A straw man argument can take several forms. It might focus on one isolated aspect of the original claim, conveniently ignoring its broader context. Alternatively, it could exaggerate or oversimplify the opponent’s position, making it appear extreme or absurd. In some cases, it involves taking statements out of context to make them sound less reasonable or easier to dismiss.

For example, someone might propose, “We should consider implementing some regulations to reduce pollution from factories.” A straw man response could be, “My opponent wants to shut down all factories and destroy the economy!” In this scenario, the original argument calls for reasonable regulation, but it is deliberately distorted into an extreme, indefensible position. This exaggerated claim is far easier to argue against than the original, more nuanced suggestion.

Straw man arguments are alarmingly common in political debates, social media discussions, and contentious topics. Their emotional persuasiveness and ability to divert attention away from the core argument make them an attractive tool for those seeking to win debates rather than foster genuine understanding. Often, they provoke the opponent into defending the distorted version of their position rather than returning to their original argument.

When a straw man argument succeeds, it can mislead the audience about the opponent’s actual stance, shift the focus away from valid evidence and reasoning, and make the opponent appear unreasonable or extreme.

The straw man fallacy is frequently paired with the red herring fallacy, where a deliberately distorted version of the argument serves as a distraction from the main issue. This combination allows the person using the fallacy to avoid addressing the core claims and evidence while keeping the discussion fixated on their artificial version of the opponent’s argument.

Addressing a straw man fallacy begins with clarifying the original argument. It is important to clearly and directly restate the initial claim to ensure everyone understands the intended meaning. Next, it helps to point out the distortion, identifying exactly how the argument was misrepresented or exaggerated. Finally, the focus should be redirected back to the original argument and its supporting evidence, steering the discussion away from the distorted version.

The straw man fallacy undermines meaningful discussion by replacing a valid argument with a misleading caricature that is far easier to attack. Effective reasoning demands that we engage with an opponent’s actual claims and evidence, not with distorted representations of them. Recognising and addressing this fallacy is essential for ensuring that discussions remain honest, focused, and productive, ultimately fostering clearer communication and better understanding.

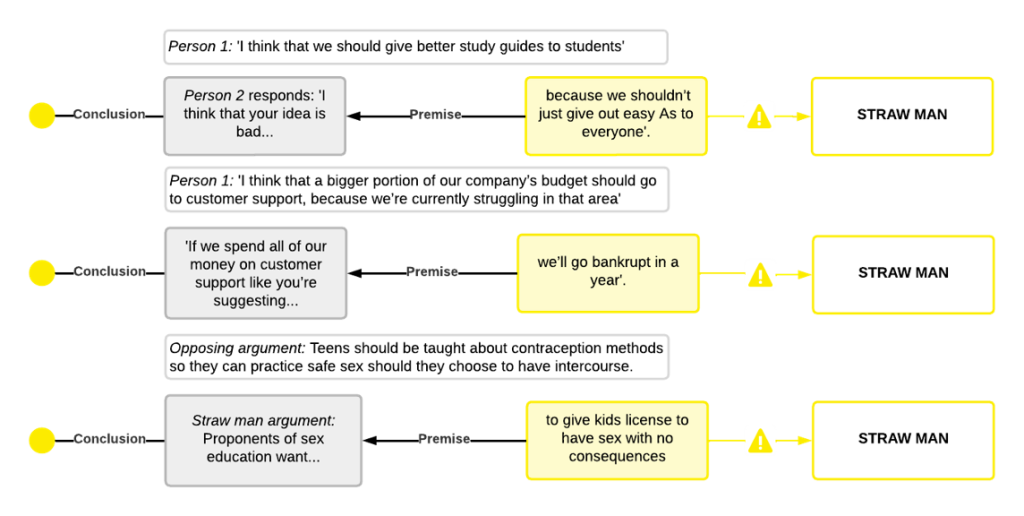

Figure 3.4.4 shows a few more examples of the straw man fallacy:

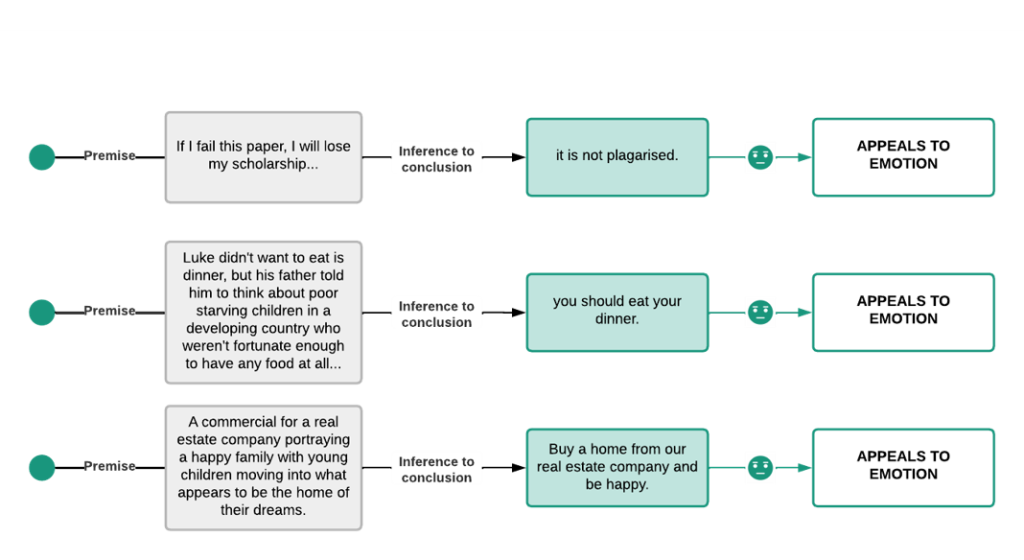

Appeals to Emotion

The appeal to emotion is a broad category of fallacies of irrelevance where arguments attempt to persuade through emotional manipulation rather than relying on reasoning and evidence. While emotions play an important role in human decision-making, they should never serve as a substitute for logical reasoning when evaluating the truth or validity of a claim.

These fallacies exploit our natural emotional responses, such as fear, pity, joy, or pride, to make arguments more persuasive. Emotional appeals are often highly effective rhetorical tools because humans are naturally responsive to emotional triggers. However, it is important to recognise that emotional reactions have no direct connection to whether a claim is true or false.

When someone uses emotion as a substitute for evidence, they bypass critical thinking by leveraging emotional influence. For example, an appeal to pity might sound like this: “You must pass me in this course because I’ve had such a hard year.” Similarly, an appeal to fear could take the form of, “If we don’t implement this policy, society will fall apart!” Meanwhile, an appeal to joy might claim, “Think of how happy you’ll be if you buy this product!” In each case, the emotional reaction is designed to override critical analysis, making the audience more likely to accept the claim without properly evaluating its logical merits.

However, not all emotional appeals are inherently fallacious. There are situations where emotions are a valid component of reasoning, particularly in moral arguments or calls to action. For instance, in moral reasoning, emotions like compassion or outrage can provide relevant context for understanding the moral weight of an issue, such as arguments concerning human rights or environmental justice. Similarly, in motivational arguments, emotions play a crucial role in inspiring action. An appeal to urgency or responsibility, for example, might be entirely appropriate when encouraging people to donate to disaster relief efforts.

Even in these cases, however, emotional appeals must complement reasoning and evidence, not replace them. Emotion can enhance persuasion, but it must never be used to suppress facts, as ignoring evidence simply because it feels uncomfortable is intellectually dishonest. Likewise, emotional discomfort does not invalidate a logically sound argument, nor can strong emotions distort objective reality.

When encountering emotional appeals, it is essential to critically examine the argument. The first step is to identify whether the argument relies on emotional triggers instead of presenting evidence. If it does, it is important to ask for clear facts or reasoning to support the claim being made. Throughout the discussion, it is equally important to remain grounded in reasoning, acknowledging the emotional component of the argument but focusing on whether it logically holds up under scrutiny.

Emotional appeals are undeniably powerful tools for persuasion, but they become fallacious when they replace reasoning and evidence instead of working alongside them. While emotions can be relevant in moral reasoning or motivational contexts, they must always remain anchored in facts and logical analysis. Effective critical thinking requires us to acknowledge emotions without allowing them to override objective reasoning, ensuring that our conclusions are based on clear evidence and rational judgement rather than fleeting emotional responses.

Figure 3.4.5 shows a few more examples of the appeals to emotion fallacy:

Chapter Attribution

Content adapted, with editorial changes, from:

Reasoning critically in Mastering thinking: Reasoning, psychology, and scientific methods (2024) by Michael Ireland, University of Southern Queensland, is used under a CC BY-SA licence.