3.5. Fallacies of Ambiguity

By Michael Ireland, adapted by Marc Chao and Muhamad Alif Bin Ibrahim

Fallacies of ambiguity occur when unclear, vague, or misleading language is used in an argument, either intentionally or unintentionally. Unlike fallacies of insufficiency, where reasoning or evidence is incomplete, or fallacies of irrelevance, where unrelated premises are introduced, fallacies of ambiguity exploit confusion over the meaning of words or phrases to create the illusion of a valid argument.

At the heart of these fallacies lies the misuse or shifting of meanings, often without clarification. Words and phrases frequently have multiple meanings, and ambiguity arises when an argument subtly shifts between these meanings without making the transition explicit. This linguistic sleight of hand creates a false impression of coherence or support for a conclusion, even though the reasoning itself remains fundamentally flawed.

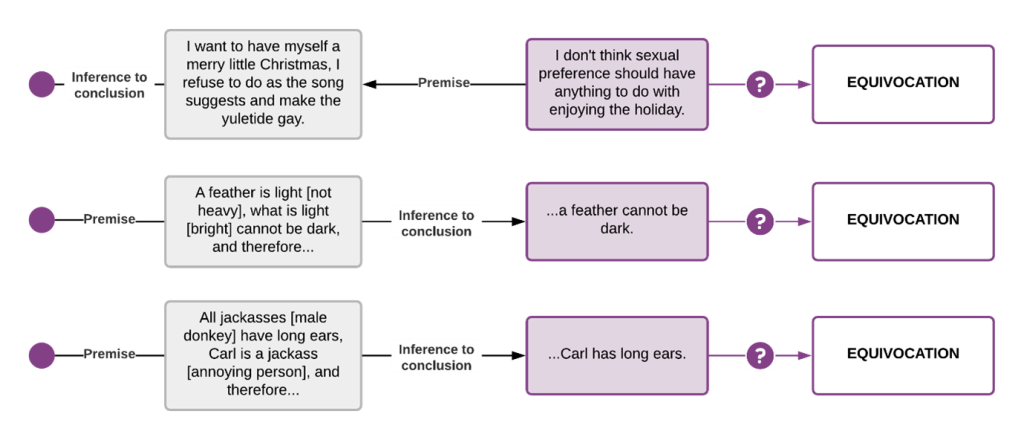

Equivocation

The equivocation fallacy occurs when a key term or phrase is used in different senses within the same argument, leading to confusion or misleading reasoning. In everyday language, it is common for words to have multiple meanings, and this is usually not an issue. However, in arguments, clarity and consistency are essential. The responsibility falls on the person presenting the argument to ensure that key terms are used consistently throughout and always refer to the same concept or idea each time they appear.

This fallacy typically occurs when a word with multiple meanings shifts subtly during the course of an argument. Sometimes, this shift is obvious and easy to spot, but in many cases, it can be surprisingly subtle and require careful attention to detail to identify.

For example, consider the following argument: “Only man is rational. No woman is a man. Therefore, no woman is rational.” In this case, the word “man” is first used to mean “human beings in general”, and then it shifts to mean “male humans”. The conclusion relies entirely on this shift in meaning to create a faulty argument.

While examples like this one are blatant, many instances of equivocation are much more difficult to detect because the shift in meaning can be nuanced or context-dependent.

Equivocation is sometimes paired with the shifting goalposts fallacy, where the criteria for evidence or reasoning are subtly adjusted during a discussion. In such cases, someone may change the definition or expectation tied to a key term, making their argument harder to challenge.

For instance, someone might say: “Science can’t explain love.” When presented with studies on the biology of love, they might shift the definition of “love” from something biological and chemical to something spiritual or metaphysical. This shift in definition undermines the discussion because it redefines the original premise to avoid being addressed directly.

To address equivocation, it is essential to clarify key terms by asking for clear and consistent definitions of important words or phrases. Pay close attention to where a term seems to shift meaning midway through the argument and ensure that key terms remain consistent from premise to conclusion.

The equivocation fallacy relies on the ambiguity of language to mislead or confuse. While some cases are easy to spot, others demand careful analysis and attention to detail. Ensuring that key terms are clearly defined and consistently applied throughout an argument is vital for maintaining logical clarity and validity. By identifying and addressing subtle shifts in meaning, we can prevent this fallacy from undermining rational discourse.

Figure 3.5.1 shows a few more examples of the equivocation fallacy:

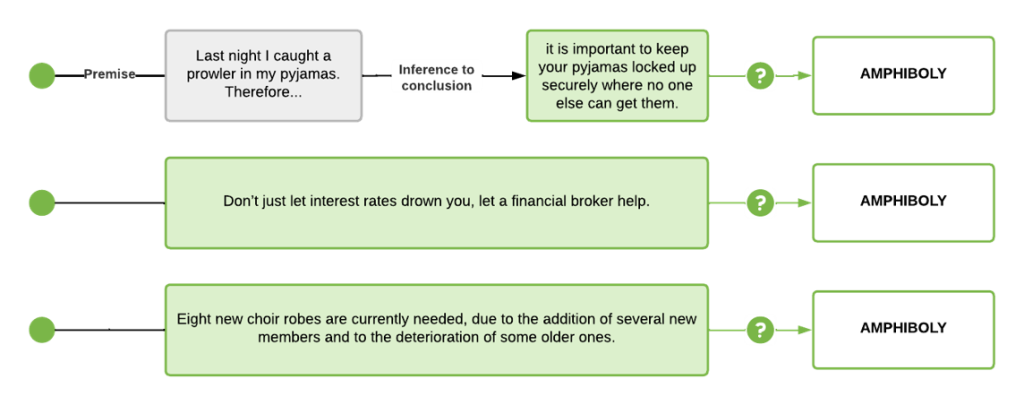

Amphiboly

The amphiboly fallacy occurs when the structure or grammar of a sentence creates ambiguity, leading to multiple interpretations that can mislead or distort reasoning. Unlike equivocation, which involves shifting the meaning of a single word, amphiboly arises from poorly constructed or ambiguous phrasing in an entire sentence or phrase. This ambiguity often allows an argument to be interpreted in more than one way, sometimes leading to faulty conclusions.

In many cases, amphiboly happens unintentionally due to awkward sentence structure or misplaced modifiers, but it can also be deliberately crafted to obscure meaning and make a weak argument seem stronger. The responsibility lies with the person presenting the argument to ensure that their phrasing is clear, precise, and unambiguous.

For example, consider the sentence: “I shot an elephant in my pyjamas.” The structure of this sentence leaves room for two interpretations: either the speaker was wearing pyjamas when they shot the elephant, or the elephant was somehow wearing the pyjamas. The ambiguity arises from the placement of the phrase “in my pyjamas”, making it unclear which subject the phrase modifies.

In arguments, amphiboly can be more subtle but equally misleading. Take this example: “The professor said on Monday he would give a lecture on ethics.” Here, it is unclear whether the professor made the statement on Monday or if the lecture will take place on Monday. This ambiguity creates room for misunderstanding and allows different interpretations to serve as a convenient escape for someone unwilling to clarify their reasoning.

Amphiboly can also intersect with other fallacies, such as red herrings or shifting goalposts, where the ambiguity is used strategically to divert attention or shift the focus of an argument. By leaving a sentence or phrase open to multiple meanings, the person using amphiboly can evade accountability or avoid addressing the central issue directly.

To address amphiboly, it is essential to clarify ambiguous phrasing by asking the speaker to restate their argument in clearer terms. Pay close attention to grammatical structure and context, and identify any points where a sentence could plausibly have more than one interpretation. In cases where the meaning remains unclear, insist on a precise explanation to ensure the argument can be properly evaluated.

The amphiboly fallacy highlights how poor grammar or sentence construction can distort reasoning and obscure the clarity of an argument. While some examples are obvious and humorous, others are far more subtle and demand careful analysis. Ensuring that sentences are well-structured and unambiguous is critical for maintaining logical consistency and clarity in arguments. By identifying and addressing amphiboly, we can prevent ambiguous phrasing from misleading discussions or undermining valid reasoning.

Figure 3.5.2 shows a few more examples of the amphiboly fallacy:

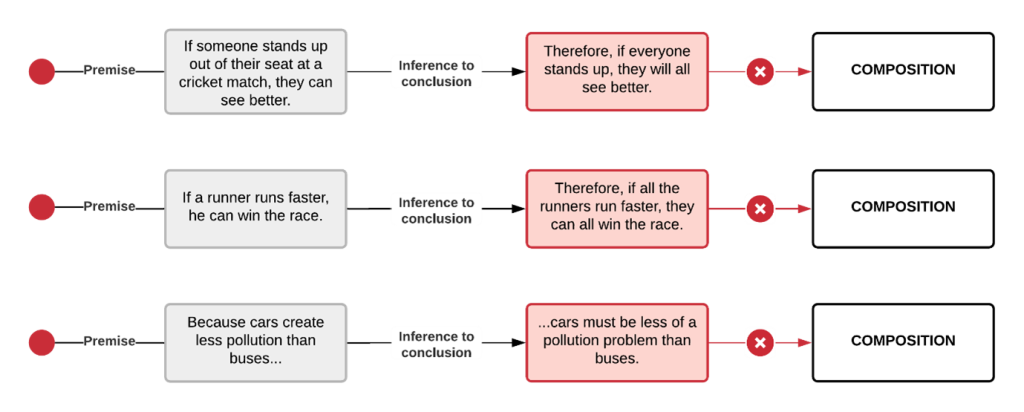

Fallacy of Composition

The fallacy of composition occurs when someone assumes that what is true of individual parts must also be true of the whole they make up. In other words, if certain components of a system or group have specific qualities, it is assumed that the entire system or group will automatically share those same qualities.

At first glance, this may seem like an obvious or trivial mistake. After all, it is common sense that a whole is not always simply the sum of its parts. However, this fallacy is far more common than it appears and often goes unnoticed in everyday conversations, marketing campaigns, and even policy discussions. Its persuasive power comes from the instinctive assumption that scaling up from individual characteristics to collective outcomes is inherently logical.

This reasoning becomes problematic because properties that exist at the level of individual components do not always transfer cleanly to the collective whole. Complex systems often exhibit emergent properties, where the group or system behaves in ways that are not directly predictable from the traits of its individual parts.

For example, someone might say, “Each player on our team is the best in their position, so our team will be the best in the league.” While it might seem reasonable at first, team success depends on collaboration, strategy, and teamwork, not just individual talent. A collection of exceptional players does not automatically guarantee an exceptional team performance.

Another example is the claim, “Every brick in this building is lightweight, so the entire building must be lightweight.” While each brick may indeed be light, the combined weight of thousands of bricks creates an extremely heavy structure. In both cases, the error arises from failing to recognise how properties at the individual level interact or change when scaled up to the collective level.

This fallacy becomes especially problematic when applied to social systems, economic policies, or scientific reasoning. For example, an economic policy that benefits individuals might unintentionally harm the larger economy when scaled up, due to systemic effects that don’t exist at the individual level. Similarly, assuming that a successful business team can be replicated identically across different contexts ignores the unique group dynamics and environmental factors that contribute to collective success.

The fallacy of composition also shares similarities with other reasoning errors. It contrasts with the fallacy of division, where someone assumes that what is true of the whole must also be true of its parts. Additionally, it overlaps with hasty generalisation, where conclusions about an entire population are drawn from observations of a small, unrepresentative sample.

This reasoning error is sometimes referred to by other names, including the Exception Fallacy and Faulty Induction. Regardless of the terminology, the core issue remains the same: the assumption that individual traits will scale up predictably to a collective level often overlooks key systemic dynamics.

To avoid falling into this trap, it is essential to carefully analyse the relationship between the parts and the whole. Ask whether the quality in question logically scales up when applied collectively. Consider whether emergent properties, which are traits or behaviours that arise only at the collective level, might alter the expected outcome. Finally, remain sceptical of blanket assumptions that project individual characteristics onto entire systems or groups.

The fallacy of composition serves as a reminder that reasoning from parts to wholes must be approached with careful analysis and a recognition of complexity. While there are instances where such reasoning holds true, it cannot be assumed as a universal rule. Developing an awareness of this fallacy helps us avoid oversimplified conclusions and ensures more precise, logical reasoning when evaluating collective claims.

Figure 3.5.3 shows a few more examples of the composition fallacy:

Fallacy of Division

The fallacy of division occurs when someone assumes that what is true of a whole must also be true of its individual parts. In other words, if a group, system, or collective possesses a certain characteristic, it does not automatically follow that each member or component of that group shares the same characteristic.

This reasoning error is essentially the reverse of the fallacy of composition, where properties of individual components are incorrectly projected onto the whole. In both cases, the mistake stems from failing to recognise the distinction between collective and individual properties. While characteristics can sometimes scale up from individuals to the group, or down from the group to individuals, they often do not, especially in complex systems where emergent properties or interactions between components play a crucial role.

For example, someone might claim, “The university is prestigious, so every professor working there must also be prestigious.” While the university as a whole may have an outstanding reputation, not every individual professor automatically shares that prestige. Institutional reputation depends on a collective contribution from faculty, administration, resources, and historical achievements, not solely on individual members.

Another example is the statement, “The basketball team is unbeatable this season, so every player on the team must also be unbeatable.” While the team might indeed be performing exceptionally well, its success likely comes from collaboration, strategy, and group dynamics, rather than every player being exceptionally skilled on their own.

The fallacy arises because group-level characteristics do not always scale down to individual members. Outcomes or traits observed at the collective level often emerge from systemic interactions, cooperation, or structural factors, which are elements that do not necessarily translate to isolated parts.

This reasoning error becomes especially harmful when it fuels stereotypes or unjust assumptions about individuals based on group-level data. For example, one might say, “Statistically, members of Group X have lower average educational outcomes; therefore, this specific individual from Group X must also be poorly educated.” This assumption is both unfair and logically flawed, as group averages cannot reliably predict individual characteristics. Data about collectives should always be interpreted with caution, especially when applied to specific cases.

The fallacy of division shares similarities with other logical missteps. It contrasts with the fallacy of composition, where individual traits are incorrectly projected onto a collective group. Additionally, it bears some resemblance to hasty generalisation, where broad conclusions are drawn from a small or unrepresentative sample. However, while hasty generalisation typically scales upward from a limited observation, the fallacy of division scales downward from a group-level observation.

This reasoning error is sometimes referred to by other names, such as False Division or Faulty Deduction. While the term “deduction” in this context can be somewhat confusing, the core issue remains the same: assuming that group-level properties apply uniformly to individual members without sufficient justification.

To avoid committing the fallacy of division, it is essential to carefully examine the relationship between the whole and its parts. Ask whether the property in question logically transfers from the collective to the individual. Be cautious of overgeneralisations based on averages or group characteristics and always consider the context, including whether the observed property depends on systemic factors or collective dynamics rather than individual traits.

The fallacy of division serves as a reminder that group-level truths cannot always be applied to individual members without careful analysis. While some properties may indeed scale down, many do not. Recognising this fallacy helps us avoid stereotyping, challenge faulty assumptions, and analyse arguments with greater precision and fairness.

Figure 3.5.4 shows a few more examples of the division fallacy:

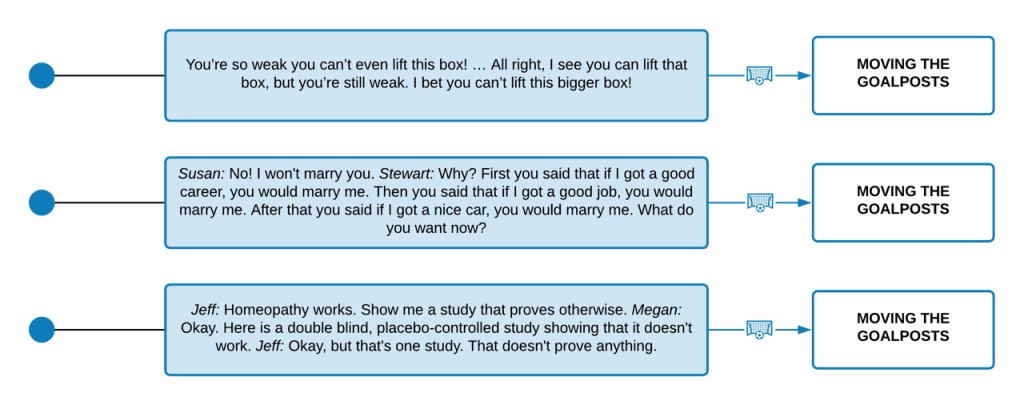

Moving the Goalposts

The “moving the goalposts” fallacy occurs when someone changes the criteria for success or acceptance in an argument after those criteria have already been met. This tactic ensures that no matter how valid or well-supported an opponent’s evidence or reasoning may be, it can never fully satisfy the evolving standards.

The metaphor originates from sports, where physically moving the goalposts would make scoring a goal impossible. In debates or discussions, the effect is the same: the standards for evidence or reasoning are repeatedly adjusted, often in increasingly unreasonable ways, to ensure that the original claim remains perpetually unproven.

This fallacy often appears when someone is unwilling to concede defeat, even when their opponent has provided clear and compelling evidence. For example, a sceptic might demand, “Show me evidence of evolution happening today.” When presented with valid examples, they might respond with, “That’s not enough; show me an example of entirely new genetic information arising by random processes.” In this case, the criteria for acceptable evidence keep shifting, making it impossible to satisfy the demands. The tactic guarantees that the person moving the goalposts can always claim the evidence is insufficient, regardless of how well it meets the original request.

The issue with moving the goalposts is that it creates unfair standards that prevent meaningful resolution. First, it establishes an intellectual dishonesty, as the person employing the tactic demonstrates a lack of genuine openness to evidence or reasoning. Second, it leads to endless demands where the discussion becomes circular, with no clear way to reach a conclusion.

This fallacy thrives in ambiguous discussions, especially when terms like “proof”, “evidence”, or “compelling reason” are left undefined. Without clarity on what constitutes acceptable evidence, one party can continuously shift expectations, making productive dialogue impossible.

To avoid falling into this trap, it is important to define clear standards at the outset of a discussion. Both parties should agree on what counts as acceptable evidence or reasoning before proceeding. Once these standards are established, they should remain consistent throughout the discussion. If someone begins altering their requirements, it is essential to politely call out the inconsistency and redirect the conversation back to the original agreement.

For example, a clear agreement might sound like this: “If I can show you two independently verifiable examples of evolution happening today, will you accept that as evidence?” Establishing this kind of standard sets clear expectations and reduces the likelihood of goalpost-shifting later in the discussion.

The “moving the goalposts” fallacy is sometimes referred to by other names, including Raising the Bar, Shifting Sands, Gravity Game, and Argument by Demanding Impossible Perfection. Each of these terms highlights the same core issue: unfairly altering the conditions for acceptance after the discussion has already begun.

Ultimately, the “moving the goalposts” fallacy undermines productive dialogue by preventing arguments from reaching a fair and meaningful resolution. Avoiding this fallacy requires clear agreements about what constitutes valid evidence, a commitment to consistent standards, and a willingness from all parties to engage in good-faith reasoning. By maintaining these principles, discussions can remain focused, fair, and intellectually honest.

Figure 3.5.5 shows a few more examples of the moving the goalposts fallacy:

Chapter Attribution

Content adapted, with editorial changes, from:

Mastering thinking: Reasoning, psychology, and scientific methods (2024) by Michael Ireland, University of Southern Queensland, is used under a CC BY-SA licence.