6.1. A Model of Scientific Research in Psychology

By Rajiv S. Jhangiani, I-Chant A. Chiang, Carrie Cuttler and Dana C. Leighton, adapted by Marc Chao and Muhamad Alif Bin Ibrahim

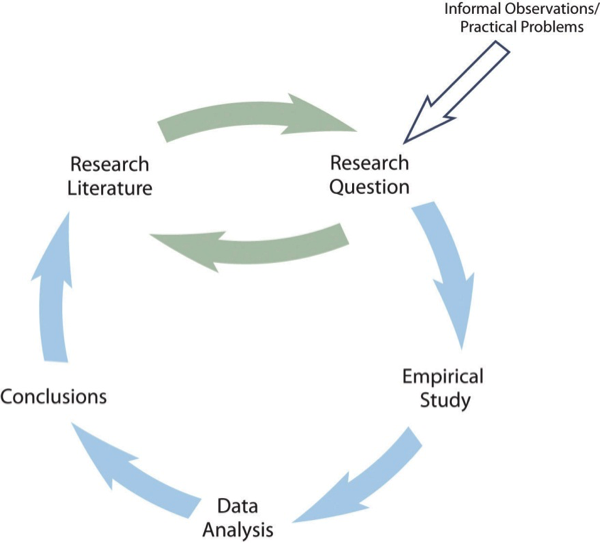

Scientific research in psychology operates as a dynamic and ongoing cycle, continually building upon itself to refine our understanding of human behaviour and mental processes. As shown in Figure 6.1.1 below, this cycle can be broken down into key stages: formulating a research question, conducting an empirical study, analysing data, drawing conclusions, and sharing the findings through publication. Each step plays a crucial role in advancing psychological knowledge, and the cycle often loops back on itself as new discoveries inspire fresh questions and further investigation.

At the heart of this cycle lies the research literature, which serves as a repository of all published scientific findings within a given field. Researchers rely on this body of work not only to ground their own investigations in established knowledge but also to identify unanswered questions or conflicting results that warrant further study. However, not all research questions originate from the literature. Sometimes, they emerge from casual observations in daily life or from pressing practical problems that demand solutions. Even in these cases, researchers typically begin by consulting the literature to see if their question has already been addressed and to refine their focus based on existing findings.

The Research Cycle in Action

The study conducted by Mehl and his colleagues serves as an excellent example of this research cycle in practice. Their investigation began with a common stereotype: the belief that women are more talkative than men. This stereotype had been perpetuated both informally in everyday conversations and, to some extent, within published claims in the research literature. However, upon closer examination of the literature, Mehl and his team realised that this question had not been adequately addressed by rigorous scientific studies.

With a refined research question in hand, they designed a carefully controlled empirical study. Participants’ conversations were systematically recorded (with their consent, of course), quantified, and analysed to determine whether women truly speak more than men. Their results revealed little meaningful difference between the two groups in terms of talkativeness. These findings challenged a widely held stereotype and provided a clear, evidence-based answer to the original question. Importantly, Mehl and his team published their results, contributing to the growing body of research literature on gender differences in communication.

But their study did not mark the end of the story. Like most research, it raised new questions. Could cultural differences affect talkativeness? Are there specific contexts in which one gender might speak more than the other? These follow-up questions offer opportunities for future studies, ensuring that the research cycle continues.

Practical Questions Driving Research

Another example of this cycle comes from a practical, real-world concern: the increasing prevalence of cell phones in the 1990s and their potential impact on driving safety. As cell phone use became widespread, both researchers and the general public began to ask whether talking on a cell phone while driving impaired performance behind the wheel.

Psychologists decided to investigate this question scientifically. Drawing on established research that multitasking tends to reduce efficiency in both tasks, they designed empirical studies comparing driving performance with and without cell phone use. These studies involved both laboratory simulations and real-world driving conditions, allowing researchers to measure drivers’ reaction times, hazard detection abilities, and vehicle control.

The findings were clear: cell phone use significantly impaired driving performance. Importantly, the studies went further to reveal nuanced insights. For example, research by Drews et al. (2004) demonstrated that conversations with a passenger were less distracting than cell phone conversations. Passengers in a car are often aware of driving conditions and may naturally adjust their behaviour, pausing their conversation during a challenging traffic situation, for instance. In contrast, someone on the other end of a phone call remains oblivious to the driver’s immediate environment, making the conversation more cognitively demanding and distracting.

Each of these studies was published and became part of the growing research literature on distracted driving. These findings did not just advance psychological science; they also had significant real-world applications, informing public policy, raising awareness about distracted driving risks, and influencing laws restricting cell phone use while driving.

For more information about how the brain processes information and what causes driver distraction, watch the following video by the American Psychological Association [3:10]:

References

Drews, F. A., Pasupathi, M., & Strayer, D. L. (2004). Passenger and cell-phone conversations in simulated driving. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting, 48(19), 2210-2212. https://doi.org/10.1177/154193120404801901

Chapter Attribution

Content adapted, with editorial changes, from:

Research methods in psychology, (4th ed.), (2019) by R. S. Jhangiani et al., Kwantlen Polytechnic University, is used under a CC BY-NC-SA licence.