2.2. Constructing an Argument

By Michael Ireland, adapted by Marc Chao and Muhamad Alif Bin Ibrahim

All statements in an argument are propositions, which means they are statements that can be either true or false. To make a proposition credible or believable, it needs the support of a strong argument. While premises within an argument serve as reasons to support the conclusion, they are not the primary focus of the argument itself. The main goal of an argument is to prove its conclusion, assuming that the premises are already justified or self-evident. If the premises need further support, they must act as conclusions in separate arguments with their own supporting premises, creating a continuous cycle of reasoning. In most arguments, however, premises are presented as either self-evident or already established. If this is not the case, the person making the argument can either provide additional support for the premises or leave it to the audience to assess their validity.

This focus on propositions is crucial because our thinking primarily occurs through words, structured into sentences or statements. While emotions and mental imagery play a role, our reasoning and communication depend on language, particularly on declarative sentences or propositions. Propositions are essential building blocks of reasoning, as they are the means through which we express and evaluate truth. In arguments, propositions are grouped together: some serve as supporting reasons (premises), while others are the main focus (conclusions). This relationship between premises and conclusions forms the foundation of critical thinking and logical reasoning.

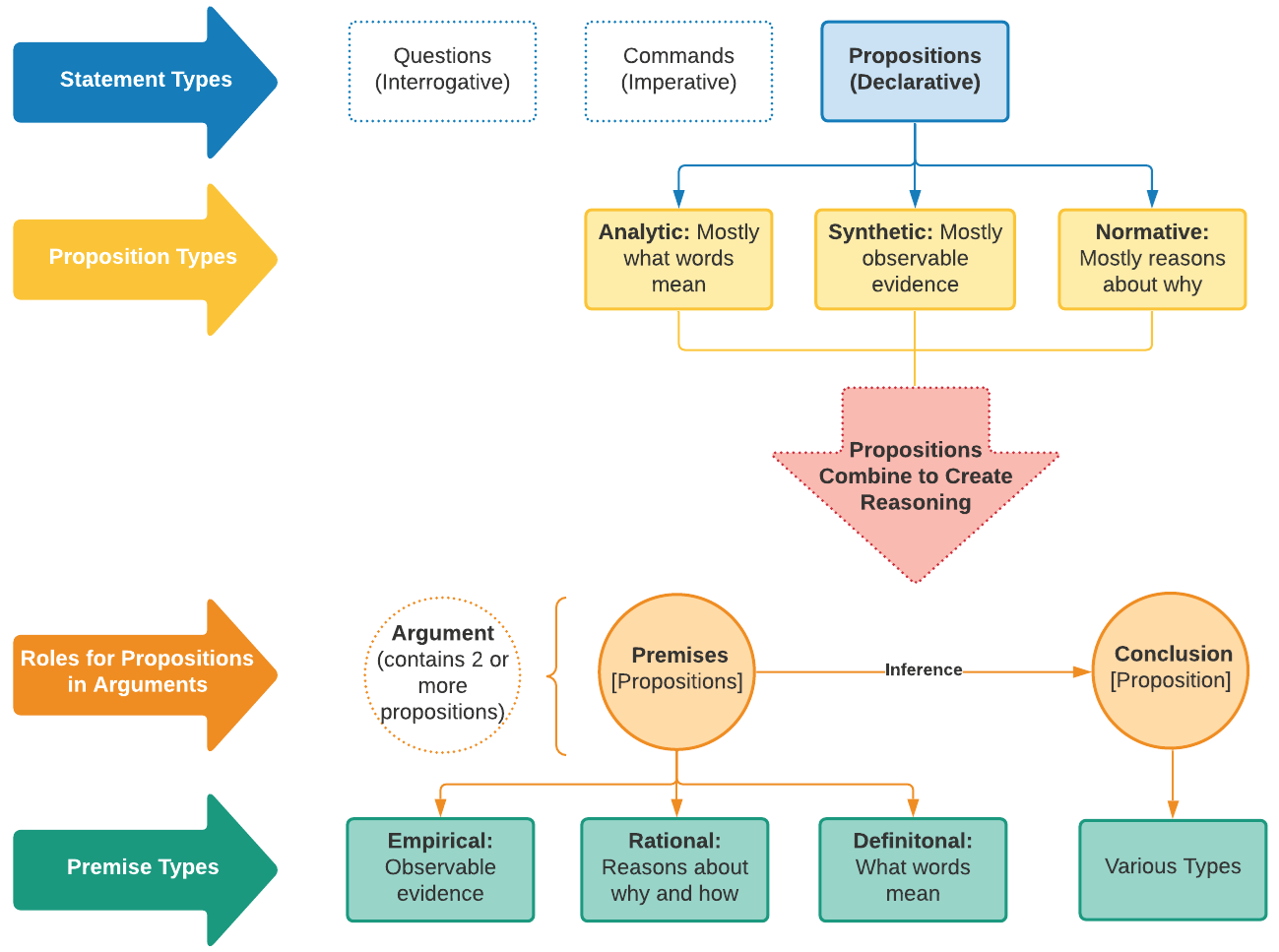

To summarise (Figure 2.2.1), propositions are a specific type of statement that makes an assertion about something being true or false. This distinguishes them from other types of statements, such as interrogative statements (questions) or imperative statements (commands or requests). Propositions are grouped in arguments to justify a conclusion, with premises acting as the supporting reasons. Premises can take different forms: they may describe the nature of things (rational premises), provide evidence from observations (empirical premises, including scientific evidence), or rely on definitions (definitional premises). Occasionally, rhetorical questions or commands might be used in arguments, though they are less formal and less convincing. Ultimately, propositions play a central role in reasoning, as they allow us to construct, evaluate, and communicate ideas effectively.

Students often struggle to distinguish between empirical and rational propositions when analysing premises in arguments. Simply put, a rational proposition explains the “why” and “how” of something without relying on direct, observable evidence. In contrast, an empirical proposition is grounded in actual observations or data. Evidence, in this context, refers to observable facts or findings that support a proposition. While a reason explains why something might be true, evidence demonstrates that it is true.

For example, consider the debate on the effectiveness of face masks. An argument in favour of enforcing masks might use an empirical premise, citing scientific studies that show communities with enforced mask mandates have lower COVID-19 transmission rates. This is empirical because it relies on observed data and measurable outcomes.

On the other hand, an argument against enforcing face masks might use a rational premise, such as claiming that COVID-19 virus particles are so small that mask fabric cannot block them, likening it to trying to stop mosquitoes with a chicken-wire fence. This reasoning is based on logical inference rather than direct observation. It could, however, be countered with another rational premise, such as the explanation that the virus spreads primarily in larger respiratory droplets, which masks are effective at blocking.

Rational claims often focus on the nature of things rather than specific observations, which can make them seem confusing. For instance, while arguments about the size of COVID-19 particles may appear empirical, they actually rely on reasoning from scientific knowledge about droplet size and mask functionality rather than presenting direct observational data.

At first glance, analysing arguments and their structure might seem overly intellectual or abstract, but this skill is highly practical in everyday life. Every belief, claim, scientific fact, or even marketing message you encounter can be understood as an implicit argument, which is an unstated combination of premises and conclusions. Nearly all beliefs can, and should, be expressed as formal arguments. Reasoning itself is the process of combining propositions into arguments and analysing those arguments to assess the credibility of their claims. Understanding this framework equips you to think critically and evaluate the reliability of the information you encounter.

- Bitcoin values will drop significantly in the next 12 months.

- Systemic racism is a serious and destructive force in modern Western societies.

- Our sports team will win the grand final.

- Human activity is causing global climate warming.

- My political party’s candidate is the best choice for president.

- Our new product will cure baldness, insomnia, wrinkles, erectile dysfunction, ageing, and more.

- My birthday party this year will be amazing.

- Critical thinking is a valuable subject to study.

One of the most important critical thinking skills you can develop is the ability to analyse these claims, which are all examples of propositions. This involves breaking them down to understand their argument structure, identifying the premises (reasons) and conclusions, and evaluating whether the premises are true and how well they support the conclusion.

Let us look at a simple example:

| Proposition (or claim) | The lecturer is a nerd. |

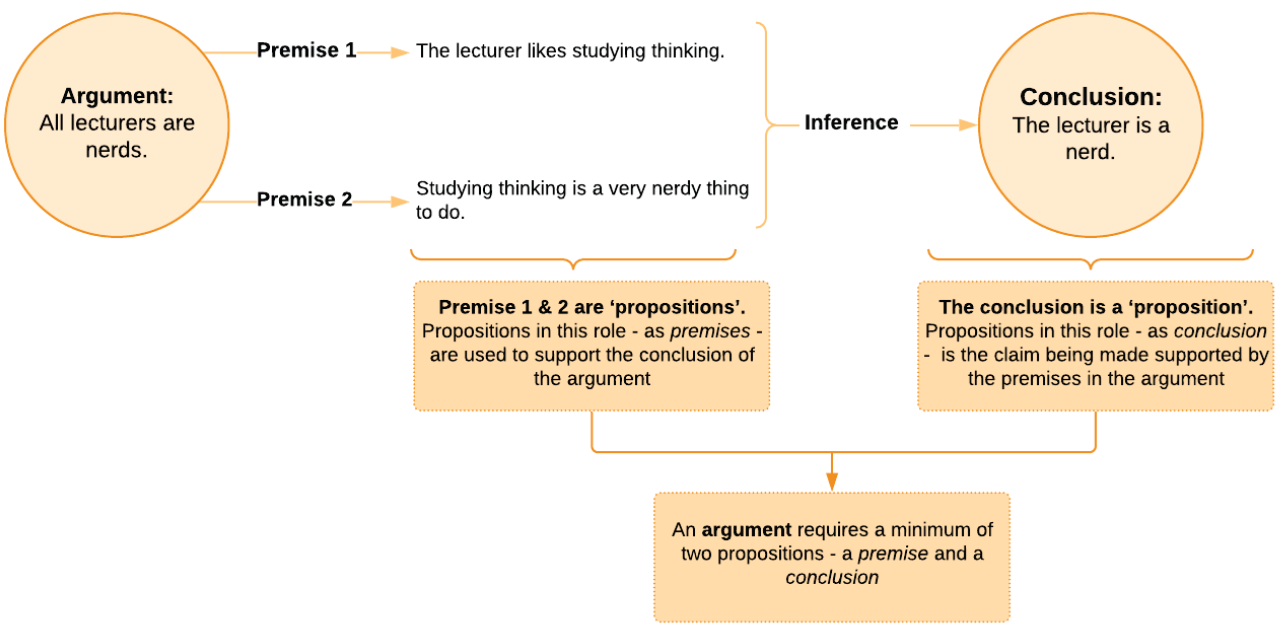

This is a proposition because it makes a claim about something, asserting that it is true. However, on its own, this statement is unconvincing because it does not provide any reasons to support the claim. Without support, it is likely to be dismissed. To justify this proposition, we need to include other statements that provide reasons for believing it. These supporting statements are called premises.

In this case, the proposition “The lecturer is a nerd” becomes the conclusion, and the premises we provide are the reasons that aim to convince others of its truth. Together, these premises and the conclusion form an argument. This process of supporting claims with premises is the foundation of constructing and evaluating arguments effectively (Figure 2.2.2).

To support my conclusion, we offer two premises. The first is empirical, based on observable evidence. For example, we might notice that the lecturer spends a lot of time studying thinking, or we could ask him, and he confirms this, which serves as evidence. The second premise is rational or definitional, focusing on the nature of studying and claiming it is a “nerdy” activity. This idea cannot be directly observed but is based on reasoning about what it means to be “nerdy”.

Interestingly, the premises in this argument could also act as conclusions in other arguments with their own supporting premises. They might even be used to justify a completely different conclusion. However, when evaluating any argument, we must examine it as a whole, considering the relationships between premises and conclusions.

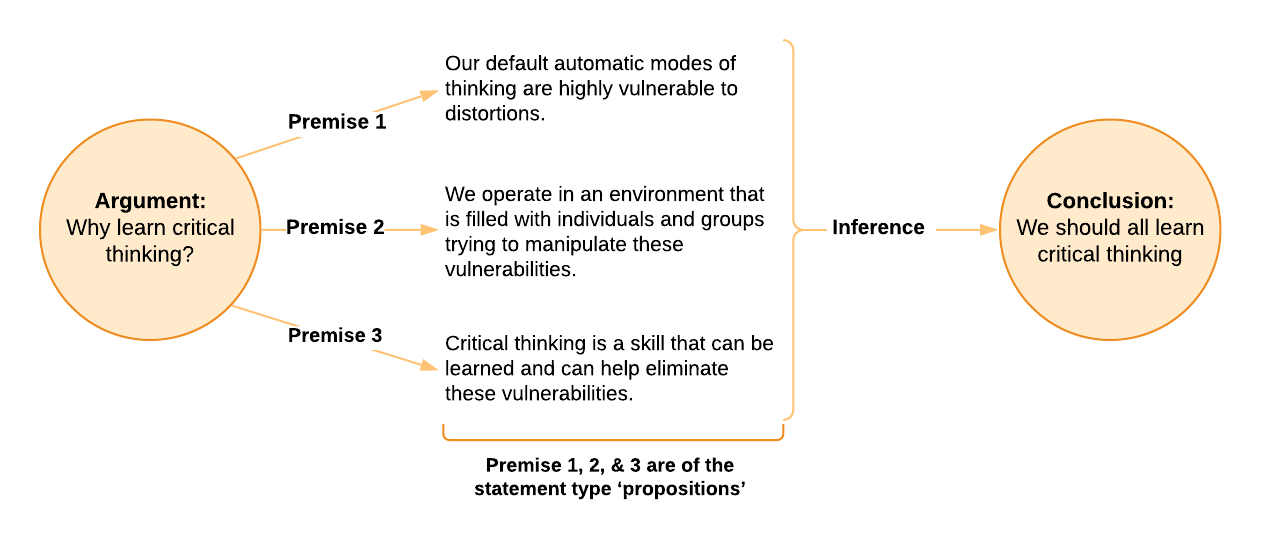

One key reason for learning critical thinking is that our brains do not naturally function optimally. This is the first lesson in critical thinking: our minds are often flawed, prone to deception, and easily misled. This recognition requires humility, which is the willingness to acknowledge that we overestimate our reasoning skills and underestimate our vulnerability to biases and distortions. Because of this, we should be modest about our beliefs and remain open to revising them. Even with strong critical thinking skills, our ideas should always be tentative, as being dogmatic or overly confident often indicates a failure to apply critical thinking. Pride in our opinions is a red flag that we may not be reasoning effectively.

Our brains evolved over millennia, not to find the “truth” but to create models of the world that support survival. Some of the errors in our thinking are deeply ingrained because they served a survival purpose for our ancestors. For example, certain delusions that enhanced survival became hardwired into our brains and are now passed on, often held passionately and without question. While our brains are powerful tools for thinking and survival, they can also limit us by locking us into beliefs that favour survival over truth.

Another reason to learn critical thinking is the environment we live in. Modern life is saturated with individuals and organisations trying to influence our thoughts and beliefs for their own ideological, political, or financial gain. We exist in a highly competitive information landscape, where ideas clash, misinformation spreads, and everyone is vying for our attention. This creates a perfect storm: our natural cognitive flaws combined with an overwhelming flood of marketing, propaganda, clickbait, and biased news make it difficult to discern truth from manipulation.

The good news is that we can improve. Through learning and practice, we can train ourselves to think more clearly and critically, reducing errors, biases, and distortions in our reasoning. These skills not only help us improve our own lives but also enable us to contribute meaningfully to our families, communities, and democratic societies.

Most claims can be expressed as arguments with premises and a conclusion. An argument is a group of statements, where one (the conclusion) is supported by the others (the premises). To illustrate this process, let us consider a simple argument with three premises and one conclusion (Figure 2.2.3).

This argument has four statements, all of which are propositions because they make claims about the world that can be true or false. The first three statements are premises, providing reasons to accept the final statement, which is the conclusion. Whether the conclusion is convincing depends on whether the premises are true and how well they logically support the conclusion. Structuring arguments in this way makes it easier to analyse and evaluate their validity and strength.

Chapter Attribution

Content adapted, with editorial changes, from:

Mastering thinking: Reasoning, psychology, and scientific methods (2024) by Michael Ireland, University of Southern Queensland, is used under a CC BY-SA licence.