3.3. Fallacies of Insufficiency

By Michael Ireland, adapted by Marc Chao and Muhamad Alif Bin Ibrahim

Fallacies of insufficiency occur when the evidence or reasons provided in an argument are inadequate to support the conclusion. In such cases, the premises fail to deliver the necessary support or justification, leaving the conclusion resting on weak or unjustified assumptions. In any argument, the burden of proof lies with the person presenting the claim, requiring them to provide sufficient evidence and sound reasoning to make their conclusion credible. When this standard is not met, the argument falls into the trap of insufficient reasoning.

Many fallacies of insufficiency stem from poorly constructed inductive arguments, including predictive inductions, generalisations, analogies, and cause-and-effect reasoning. These forms of reasoning, when properly executed, can be powerful tools for drawing conclusions from evidence. However, if the premises lack sufficient detail, breadth, or accuracy, the resulting argument will be weak and unreliable.

What makes these fallacies particularly notable is that they often present their premises as though they should be convincing in isolation, without acknowledging the gaps in reasoning that weaken the argument. In many cases, these arguments are not entirely false, they are simply incomplete. With additional premises, more robust evidence, or clearer reasoning, many of these arguments could potentially be strengthened and made persuasive.

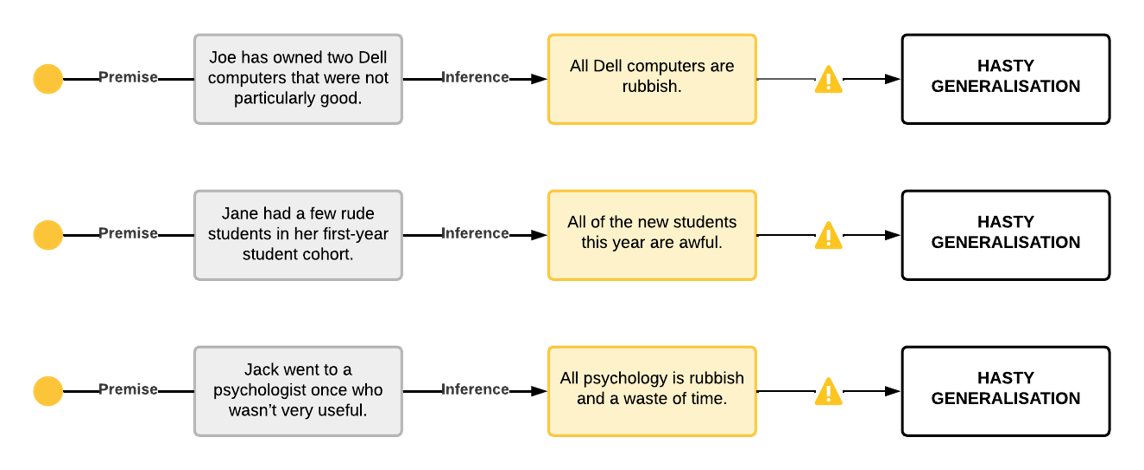

Hasty Generalisation

The hasty generalisation fallacy occurs when someone draws a broad conclusion about an entire group or category based on an inadequate, biased, or unrepresentative sample. Inductive reasoning often involves making generalisations from specific examples, but if the sample is too small, poorly selected, or otherwise flawed, the resulting conclusion lacks credibility and cannot be logically defended.

For instance, if someone visits one restaurant in a new city, has a bad experience, and then declares, “All restaurants in this city are terrible”, they are committing a hasty generalisation. The sample size in this case, a single restaurant, is far too small to justify such a sweeping conclusion.

This fallacy is particularly problematic because it often serves as the foundation for stereotypes and prejudice. Stereotypes frequently emerge from our tendency to cling to weak evidence or overextend limited observations to represent entire groups. This behaviour is often motivated by a desire to reduce uncertainty or simplify complex realities. When confronted with limited information, the human mind is prone to jumping to conclusions rather than seeking more robust evidence.

Hasty generalisations are widespread in both casual conversations and formal arguments. The fallacy also manifests in several common variations, including Insufficient Sample, where conclusions are drawn from too few examples; Converse Accident, where a general rule is misapplied to an exceptional case; Faulty Generalisation, where broad claims are made without sufficient evidence; Biased Generalisation, where the sample is unrepresentative of the larger group; and Jumping to Conclusions, where premature assumptions are made without adequate evidence. Despite their differences in appearance, these variations all share the same fundamental flaw: the evidence provided is simply insufficient to support the conclusion.

Recognising the hasty generalisation fallacy is essential for developing stronger reasoning skills. Effective inductive reasoning requires attention to sample size, representativeness, and the reliability of the evidence being presented. Before drawing broad conclusions, it is crucial to evaluate whether the examples used are sufficient and representative of the larger context.

By remaining mindful of these factors, we can avoid making sweeping claims based on weak premises. Instead, our arguments will be grounded in logic, well-supported by evidence, and ultimately far more persuasive and credible. Understanding and avoiding hasty generalisations not only strengthens our reasoning but also helps prevent the spread of harmful stereotypes and misinformation.

Figure 3.3.1 shows a few more examples of hasty generalisation:

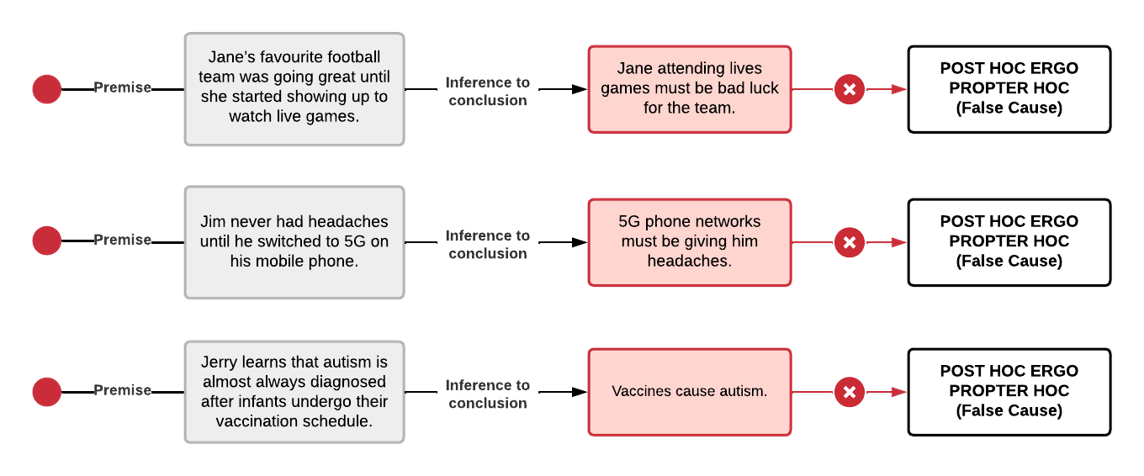

Post Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc (False Cause)

The Post Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc fallacy, often shortened to post hoc fallacy, arises from the mistaken belief that because one event follows another, the first event must have caused the second. The Latin phrase translates to “after this, therefore because of this”, capturing the core assumption of this reasoning error. While identifying cause-and-effect relationships is a central goal of inductive reasoning, establishing such relationships with certainty is notoriously difficult. The post hoc fallacy represents a common pitfall in causal reasoning, where causation is inferred without sufficient evidence to justify the conclusion.

For an argument to credibly assert a cause-and-effect relationship, it must satisfy three key conditions. First, there must be a correlation, which is a measurable relationship between the two phenomena. Second, there must be temporal order, meaning the supposed cause must occur before the effect because an effect cannot precede its cause. Third, alternative causes or confounding factors must be ruled out, ensuring that other possible explanations are not misleadingly attributed to the relationship.

In strong inductive arguments about causality, the premises must address all three of these conditions. When one or more of these criteria are ignored or insufficiently supported, the reasoning becomes fallacious, and the argument falls into the trap of post hoc reasoning.

At its root, this fallacy represents a premature assumption of causality. It occurs when someone jumps to the conclusion that one event caused another simply because they happened in sequence. However, correlation does not equal causation, and two events occurring consecutively may have no meaningful connection whatsoever.

This fallacy is frequently seen in superstitious thinking or casual observations where patterns are misinterpreted as causal links. For example, someone might say, “I wore my lucky socks, and my team won the game. Therefore, my socks caused the victory.” Or another might claim, “Every time I wash my car, it rains the next day. Washing my car must cause rain.” In both cases, the reasoning is flawed because the arguments fail to eliminate alternative explanations or demonstrate a genuine causal connection between the events.

Recognising and understanding the post hoc fallacy is essential for evaluating causal arguments critically. Just because two events occur in succession does not mean one caused the other. Proper reasoning requires us to look beyond simple correlations and carefully examine whether the relationship satisfies the three key conditions for causality. Without this scrutiny, we risk drawing misleading conclusions based on coincidence or superficial patterns rather than on solid evidence and sound reasoning.

Figure 3.3.2 shows a few more examples of the post hoc fallacy:

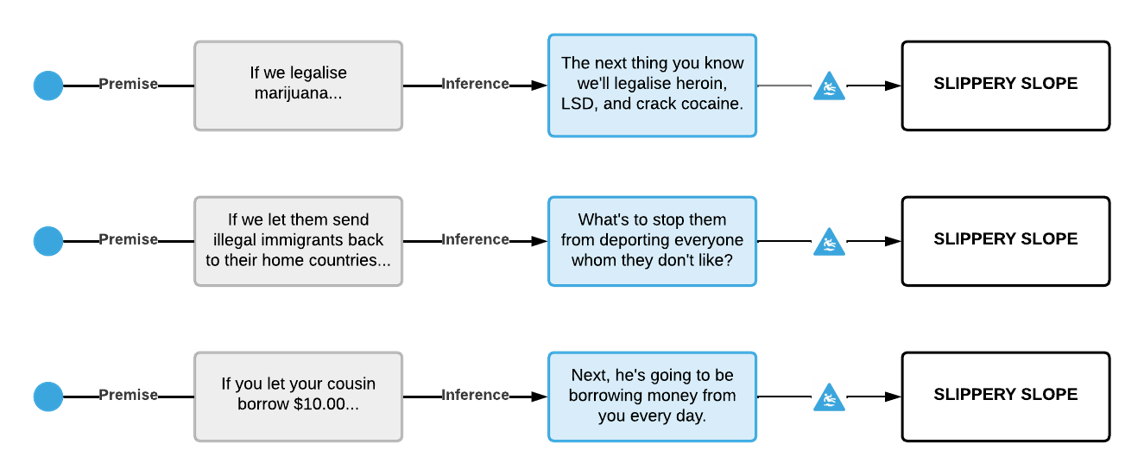

Slippery Slope

The slippery slope fallacy occurs when an argument predicts a chain of future events without sufficient evidence to support the claim. In these scenarios, one initial action is presented as the trigger for an unstoppable series of increasingly severe or extreme consequences. However, predictions about future outcomes must be backed by their own reasoning and evidence, and they cannot simply be assumed or asserted without justification.

These arguments often rely on a “give an inch, take a mile” style of reasoning, appealing to the imagery of a domino effect or chain reaction where one event inevitably leads to another, often disastrous, outcome. In many cases, slippery slope arguments are accompanied by appeals to fear or appeals to inevitability, focusing on worst-case scenarios rather than presenting a logical, evidence-based progression from one event to the next.

It is important to recognise that not all slippery slope arguments are fallacious. There are situations where a sequence of events is genuinely plausible and well-supported by evidence. For example, in a hypothetical syllogism, a chain of reasoning can be valid if each step logically follows from the previous one and is supported by clear evidence. The fallacy arises specifically when the argument overreaches, making assumptions about future outcomes without adequate reasoning or supporting evidence.

For instance, someone might claim, “If we allow one student to hand in their assignment late, soon everyone will start missing deadlines, and eventually, academic standards will collapse entirely.” At first glance, this argument seems plausible, but upon closer examination, it becomes clear that no evidence is provided to support the claim that leniency in one instance will trigger widespread academic decline. However, if the speaker were to present data showing past examples where such leniency led to systemic issues with deadlines and accountability, the argument would transition from being fallacious to plausible, becoming a legitimate concern supported by evidence.

The key difference lies in whether the chain of events is supported by logical reasoning and evidence or merely assumed through speculation and fear-mongering. Valid slippery slope arguments are carefully constructed, showing clear causal links between each step, while fallacious ones rely on exaggeration and emotional appeal rather than well-reasoned analysis.

Understanding this distinction is essential for evaluating slippery slope claims effectively. While it is wise to consider potential consequences of actions, it is equally important to demand evidence for each step in the predicted sequence. Without this evidence, slippery slope arguments remain speculative and unconvincing, serving more as rhetorical devices than as reliable reasoning. Recognising when this fallacy is at play helps ensure that discussions remain focused on evidence and logic rather than being derailed by unfounded assumptions or exaggerated fears.

Figure 3.3.3 shows a few more examples of the slippery slope fallacy:

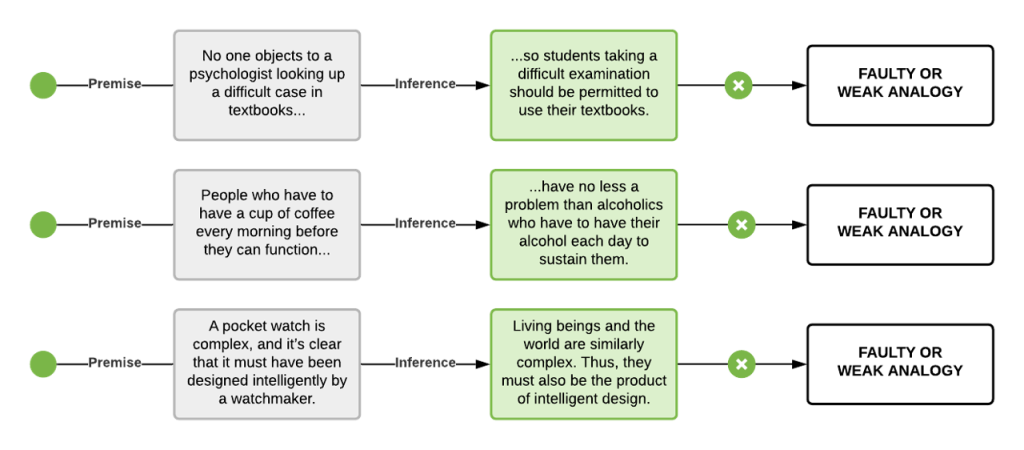

Faulty or Weak Analogy

A faulty or weak analogy occurs when an argument compares two things that are not sufficiently similar in relevant ways to support its conclusion. Like causal fallacies and hasty generalisations, this error represents a breakdown in inductive reasoning, specifically in the use of analogies to infer conclusions. While analogies can be a powerful tool in reasoning, they become fallacious when the similarities between the compared items are superficial, irrelevant, or insufficient to justify the argument’s conclusion.

In inductive reasoning, an analogy operates by suggesting that because two things are alike in certain respects, they must also be alike in other respects. However, if the shared similarities are trivial or unrelated to the core point being argued, the analogy fails to provide valid support for the conclusion.

For example, someone might say: “Employees are like nails. Just as nails must be hit on the head to work properly, employees must be managed with strict discipline to be effective.” At first glance, this comparison might appear clever or even insightful. However, the similarity between nails and employees is superficial and irrelevant to the argument about workplace management. Upon closer inspection, it becomes clear that employees are complex human beings, capable of thought, creativity, and emotion, while nails are inanimate objects with no agency or capacity for reasoning. The analogy collapses under scrutiny because the comparison is based on irrelevant similarities and ignores crucial differences.

This fallacy is known by several other names, including Bad Analogy, False Analogy, Questionable Analogy, Argument from Spurious Similarity, and False Metaphor. Despite the variety of terms, they all describe the same fundamental error: drawing conclusions from a comparison where the similarities are either superficial or unrelated to the argument’s purpose.

While analogies can serve as effective tools for clarifying ideas, illustrating concepts, and supporting arguments, they must always be evaluated critically. The strength of an analogy hinges on whether the similarities are significant and relevant to the conclusion being drawn. If they are not, then no matter how persuasive or clever the comparison might initially seem, the argument remains fundamentally flawed.

In essence, strong analogies rely on meaningful and relevant similarities, while weak analogies fail because their comparisons are superficial or unrelated to the argument’s central point. Recognising this distinction is key to using analogies effectively and avoiding fallacious reasoning. By approaching analogies with a critical eye, we can ensure they serve as reliable tools for reasoning rather than misleading rhetorical devices.

Figure 3.3.4 shows a few more examples of the weak or faulty analogies:

Argumentum ad Verecundiam (Appeal to Authority, Unqualified)

The appeal to authority fallacy, also known as argumentum ad verecundiam, occurs when someone cites an authority figure to support a claim, but the authority in question is either unqualified or irrelevant to the topic at hand. While this fallacy could also be classified under fallacies of irrelevance, it often reflects insufficient reasoning because it relies on the credibility of an authority figure without offering supporting evidence or a valid rationale for the claim.

At its core, this fallacy assumes that if an authority figure believes something, it must be true. However, history offers numerous examples of brilliant individuals holding incorrect or questionable beliefs. For instance, Isaac Newton, one of the greatest scientific minds in history, dedicated significant time to alchemy and apocalyptic predictions, pursuits that lacked scientific validity. Similarly, while Albert Einstein’s political opinions might be thought-provoking, they are not inherently more credible than those of a political scientist. Quoting Einstein to support a political argument would be as misguided as quoting a political theorist on the nuances of special relativity theory.

This fallacy is especially common in social media debates, where individuals frequently invoke famous names to bolster their arguments, regardless of whether those figures have relevant expertise in the subject being discussed. The assumption seems to be that fame or success in one domain automatically translates to authority in all others, which is rarely the case.

It is essential to clarify that not all appeals to authority are fallacious. When done correctly, referencing an authority figure can serve as a shorthand for appealing to the current state of knowledge, scientific consensus, or credible expertise. However, the strength of such an argument does not stem from the individual making the claim, but from the evidence and reasoning they represent.

For instance, citing Stephen Hawking’s views on black holes is not fallacious because his perspective represents decades of rigorous scientific research and consensus. Similarly, trusting medical advice from a qualified doctor is not an appeal to blind faith but rather reliance on their training, expertise, and evidence-based knowledge. In both examples, the authority figure serves as a conduit for established evidence and knowledge, rather than being the sole justification for the claim.

The appeal to authority fallacy typically emerges in two scenarios. The first is irrelevant expertise, where the authority figure cited lacks expertise in the specific subject being discussed. For example, relying on a physicist’s opinion on nutrition science would be inappropriate because their area of expertise does not extend to dietary research. The second scenario involves a lack of verification, where the authority figure’s expertise is either not properly substantiated or no additional evidence is provided to justify why their opinion should be trusted.

For example, someone might say, “97% of climate scientists believe in human-caused climate change, so it must be true.” While this claim references expert consensus and is not technically fallacious, it is unpersuasive on its own. A stronger argument would explain why these scientists believe this, referring to the evidence and reasoning supporting their consensus rather than relying solely on the percentage figure.

The key takeaway is that appeals to authority are not inherently fallacious, but they become weak arguments when they rely solely on the reputation of the authority figure rather than the evidence they represent. Whenever possible, it is better to focus on the reasoning and evidence behind a claim rather than the authority delivering it. While authority can add credibility to an argument, it should never replace clear reasoning and verifiable evidence. Recognising this fallacy helps ensure that discussions remain grounded in sound reasoning rather than misplaced reliance on perceived authority.

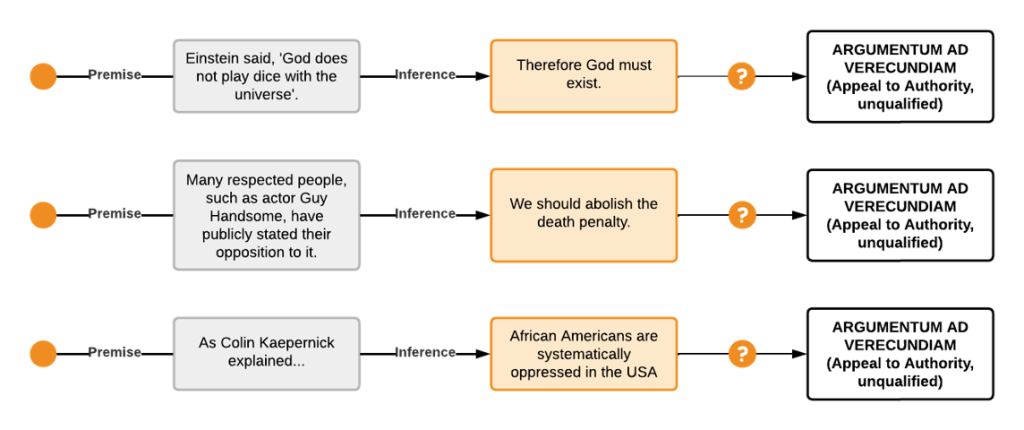

Figure 3.3.5 shows a few more examples of the appeal to authority fallacy:

Argumentum ad Ignorantiam (Appeal to Ignorance)

The appeal to ignorance (argumentum ad ignorantiam) occurs when someone argues that a claim must be true simply because there is no evidence proving it false, or conversely, false because there is no evidence proving it true. Rational thinking does not operate on the assumption that something is true until proven false or false until proven true. A lack of evidence is not evidence in itself and cannot be used to justify any positive conclusion.

This fallacy is often intertwined with the shifting of the burden of proof, another common reasoning error. In any argument, the responsibility to provide evidence lies with the person making the positive claim. Simply stating, “No one has disproven my claim”, does not qualify as valid support for that claim. The obligation to provide reasoning and evidence cannot be transferred to someone else.

You will frequently encounter this fallacy in pseudoscience and certain commercial industries, such as dieting, supplements, and beauty products. These fields often rely on the absence of disproof rather than presenting robust evidence to substantiate their claims. For example, a beauty product might claim to reduce wrinkles and add, “No study has proven otherwise”. Such reasoning shifts the focus away from the lack of supporting evidence and places an unfair expectation on others to disprove the claim.

This fallacy also tends to arise when people hold strong personal beliefs or have an emotional attachment to an idea. When someone feels deeply invested in a claim, they may demand that others disprove it instead of offering their own evidence to support it. For instance, an astrology enthusiast might argue, “You can’t prove astrology doesn’t work, so it must be true.” This reasoning is flawed because the responsibility to provide evidence always rests with the person making the positive claim. In such situations, the most rational response is to remain sceptical and withhold belief until sufficient evidence is provided.

However, it is important to note that in certain contexts, a lack of evidence can be meaningful, particularly in scientific research. When scientists actively test a hypothesis and repeatedly fail to find supporting evidence despite rigorous attempts, this absence of evidence becomes significant and can be a valid reason for rejecting the hypothesis.

For example, consider the claim: “There’s no evidence that childhood vaccinations are linked to autism.” This statement is not an appeal to ignorance because scientists have spent decades conducting rigorous studies on this hypothesis. Despite extensive research, no credible evidence has been found to support the claim. In this case, the absence of evidence is not due to a lack of investigation, but rather a consistent pattern of negative results. Accepting this conclusion is therefore rational and justified.

The appeal to ignorance fallacy happens when someone uses a lack of evidence as proof of their claim, rather than presenting positive evidence to support it. Rational reasoning requires that those making a claim bear the burden of proof and provide clear, verifiable evidence for their position. While scientific findings sometimes rely on an absence of evidence, this approach is only valid when a thorough investigation has been conducted and no supporting data has been found despite consistent effort.

A lack of evidence is not the same as evidence of absence, unless it is backed by a thorough investigation and consistent findings. In situations where evidence is unclear or incomplete, scepticism and critical thinking remain essential tools for evaluating such claims responsibly.

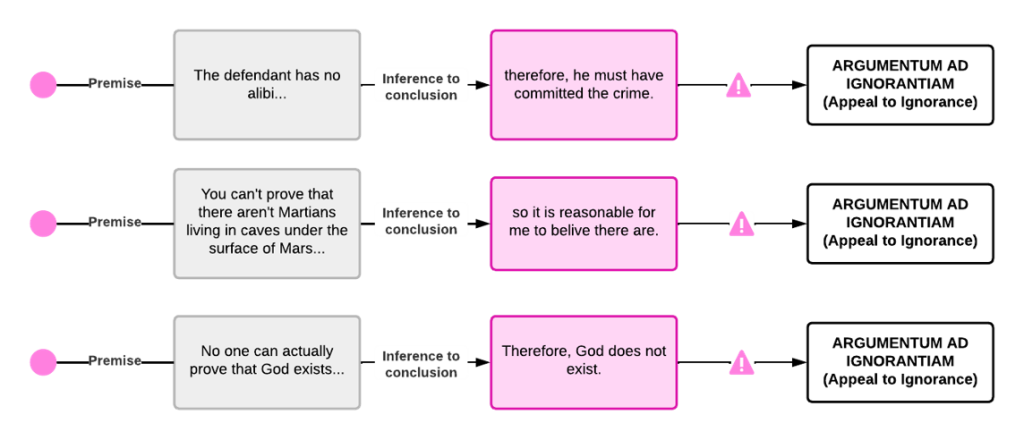

Figure 3.3.6 shows a few more examples of the appeal to ignorance fallacy:

Petitio Principii (Begging the Question)

The Petitio Principii fallacy, commonly known as begging the question, occurs when an argument’s premises assume the truth of its conclusion rather than offering independent evidence to support it. In essence, the conclusion is subtly embedded or rephrased within the premises, creating a circular reasoning pattern that offers an illusion of support without introducing any new information.

This fallacy is often misunderstood in casual conversation. In everyday language, people use “begs the question” to mean “raises the question”, as in: “John is smart, and it begs the question: Why is he with that girl?” However, in the context of logical reasoning, begging the question specifically refers to an argument where the premise and conclusion are essentially saying the same thing in different words.

In circular reasoning, the argument creates a loop where the premise depends on the conclusion being true and vice versa. While this structure might sound persuasive, it ultimately fails to provide meaningful support for the claim being made. For example, consider the claim: “The new health supplement is effective because it’s the most popular product on the market for improving energy levels.” Here, the premise (it’s the most popular product on the market for improving energy levels) assumes the conclusion (the health supplement is effective) is already true. At the same time, the conclusion (the health supplement is effective) is justified by the premise (its popularity). This creates a circular relationship where no independent evidence supports the supplement’s effectiveness. Another example is the statement: “Everyone wants the new iPhone because it’s the hottest new gadget on the market.” In this case, the premise (it’s the hottest new gadget on the market) is essentially a reworded version of the conclusion (everyone wants it). No external reasoning or evidence is provided to explain why the iPhone is desirable, resulting in circular reasoning. In both examples, the premises merely restate the conclusion in slightly altered language, failing to offer any genuine support or meaningful justification.

This fallacy is also referred to by other names, including Circular Argument, Circulus in Probando, and Vicious Circle. Each of these terms points to the same flaw: using the conclusion as evidence for itself rather than providing independent support.

Circular arguments are fallacious because they fail to advance reasoning or introduce new evidence. They may appear persuasive on the surface because of their repetitive structure, but ultimately, they lack the foundation needed for a sound argument. When evaluating an argument for this fallacy, consider the following: Is the premise offering independent support for the conclusion, or is it just rephrasing it? And, if the premise were removed, would the conclusion still hold up on its own?

To address circular reasoning, it is helpful to ask for independent evidence that does not rely on the conclusion being true. Clarifying the structure of the argument can also reveal whether the premise and conclusion are genuinely distinct claims. Additionally, focusing on external justification in the form of facts, data, or logic that exist outside of the premise–conclusion loop helps prevent this fallacy from undermining meaningful discussion.

The Petitio Principii fallacy ultimately undermines logical reasoning by recycling the conclusion as a premise, creating an endless loop of unsupported reasoning. Effective critical thinking requires the ability to identify circular reasoning patterns, demand independent evidence, and ensure that premises provide genuine support for conclusions rather than simply rephrasing them.

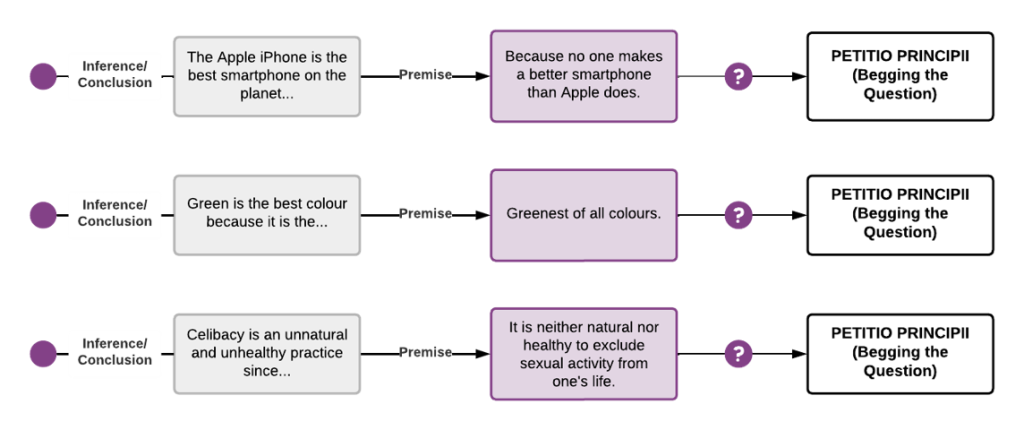

Figure 3.3.7 shows a few more examples of the begging the question fallacy:

False Dichotomy

A false dichotomy occurs when an argument presents only two mutually exclusive options as if they are the only possible choices, even though there are usually many more alternatives available. This fallacy oversimplifies complex issues, reducing them to a black-and-white scenario while ignoring the nuance and variety of real-world possibilities.

In many instances, false dichotomies are a deliberate rhetorical strategy used to manipulate or limit an audience’s perception of their available choices. By framing a situation as an “either/or” decision, the speaker attempts to make their preferred choice seem more reasonable or compelling while dismissing or hiding other potential alternatives.

This fallacy often reveals itself through key phrases like “the only alternative” or through the frequent use of the word “or” in the argument’s premises. It is a particularly common tactic in political speeches, where speakers simplify multifaceted policy issues into two extreme and seemingly opposed choices to sway public opinion or galvanise support.

For example, someone might say, “You’re either with us, or you’re against us”, or claim, “We must either increase surveillance or face total chaos in society”. In both cases, the argument artificially limits the options to only two extremes, ignoring the possibility of more balanced or alternative approaches that might exist between or beyond the presented choices.

The false dichotomy fallacy is known by several other names, including False Dilemma, All-or-Nothing Fallacy, Either/Or Fallacy, Black-and-White Thinking, Polarisation, Fallacy of False Choice, Fallacy of Exhaustive Hypotheses, No Middle Ground, and Bifurcation. Despite these different names, they all refer to the same fundamental error: reducing a complex situation to an oversimplified binary choice.

False dichotomies are problematic because they limit critical thinking and oversimplify complex problems. They force people into making decisions based on artificially restricted choices, preventing them from considering alternative solutions or exploring middle-ground positions that might offer better outcomes.

To identify and counter a false dichotomy, it is important to ask whether there are other possibilities beyond the two presented options. Consider whether the choices are genuinely mutually exclusive or if they might coexist or overlap in some way. It is also useful to examine whether the argument relies on an oversimplification of an inherently complex issue.

Recognising and challenging false dichotomies helps to prevent being cornered into false choices and allows for more thoughtful and nuanced reasoning. By doing so, we can approach complex issues with clarity and openness, avoiding the pitfalls of oversimplification and exploring the full range of available possibilities before making decisions.

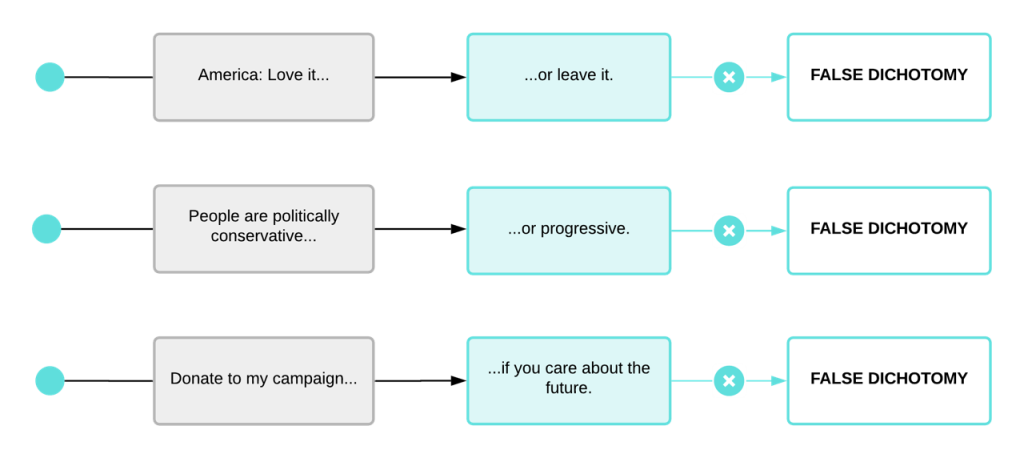

Figure 3.3.8 shows a few more examples of the false dichotomy fallacy:

Chapter Attribution

Content adapted, with editorial changes, from:

Mastering thinking: Reasoning, psychology, and scientific methods (2024) by Michael Ireland, University of Southern Queensland, is used under a CC BY-SA licence.