4.1. Perception

By Judith Rafferty, adapted by Marc Chao and Muhamad Alif Bin Ibrahim

Have you ever listened to two people recall an incident and found their stories so different that you wondered if they were even talking about the same event? This striking divergence often stems from differences in sensory perception and the many factors that shape and influence how people perceive events. Sensory perception provides a useful starting point for understanding these differences.

In this section, we use the term perception to refer to the experiences that result from the stimulation of our senses and the process of making meaning from those experiences. Perception is not static. Instead, it evolves and changes based on the information we receive. While perception may often seem automatic, it is actually a complex and dynamic process that supports our actions. Imagine how you would perceive the world without your senses, such as sight, touch, smell, taste, or hearing. It would be impossible to navigate or understand your surroundings.

To introduce the concept of perception, watch the video by CrashCourse: Perceiving is Believing: Crash Course Psychology #7 up to 3:51.

In the video, Hank Green describes perception as “the top-down way our brains organise and interpret information and put it into context” (we will explore the term “top-down” in more detail shortly). Every brain is unique, shaped by a combination of genetic makeup and environmental factors during development. This means that how we organise, interpret, and contextualise information is heavily influenced by our nature, experiences, emotions, social environments, and cultures. Acknowledging our own “lens” and biases, meaning how we perceive and assign meaning to incoming information, is essential for developing strong critical thinking skills and appreciating the diverse perspectives people bring to discussions and problem-solving situations.

It is also important to recognise that our perceptions are not always accurate and can be easily fooled. For example, watch this optical illusion video by eChalk, which demonstrates how our visual perception can deceive us [2:05].

As Hank Green states in Perceiving is Believing: “Sometimes, what you see is not actually what you get.” Similarly, Feldman Barrett (2017) explains in her book How Emotions Are Made that “you see what your brain believes” (p. 78). Feldman Barrett refers to this phenomenon as “affective realism”, which she explores in greater detail. Understanding that our beliefs influence our perceptions can also help us see how these beliefs shape our emotions.

Bottom-Up and Top-Down Processing

Bottom-up processing is often described as “data-driven” because it begins with our sensory receptors. These receptors gather sensory information from the environment and send signals to the brain, which then processes the data to construct a perception. This type of processing relies solely on the sensory input itself.

In contrast, top-down processing occurs when we interpret sensory information based on our prior experiences, knowledge, and expectations. This is often referred to as concept-driven or schema-driven processing because it uses pre-existing mental frameworks to make sense of what we perceive.

Take a look at the following image in Figure 4.1.1. What do you see? Spend a few moments trying to make sense of the black blobs in the picture.

If you have never seen this image before, you will likely continue seeing random black blobs, no matter how long you look. This demonstrates how bottom-up processing, such as sensory stimulation alone, can be insufficient to create an accurate perception. However, once you know what the picture depicts (a Dalmatian sniffing the ground in front of a tree), your perception changes dramatically. As Feldman Barrett (2017) explains, “once you have been cured of your experimental blindness” (p. 26), your brain groups certain blobs as part of the Dalmatian and others as shadows in the background.

This shift occurs because neurons in your visual cortex adjust their firing, creating connections and outlines that are not physically present in the image. Essentially, your brain constructs the Dalmatian based on your new understanding of the image, a classic example of top-down processing. From this point onward, you will likely recognise the Dalmatian in the picture every time you see it, thanks to your prior knowledge.

The Gestalt Approach

The Gestalt approach provides another perspective on how we understand and interpret perception, offering principles that are highly relevant to critical thinking. Table 4.1.1 below lists the key principles of the Gestalt approach.

One particularly interesting principle is “closure”, which refers to our tendency to fill in missing or incomplete information to create a cohesive image. This principle extends beyond visual perception and influences how we process and interpret information in general. In critical thinking, this tendency can lead individuals to fill in gaps in knowledge or reasoning with assumptions that align with their pre-existing beliefs or perspectives.

| Principle | Description | Example | Image |

| Figure-ground relationship | We structure input so that we always see a figure (image) against a ground (background). | At right, you may see a vase or you may see two faces, but in either case, you will organise the image as a figure against a ground. |  |

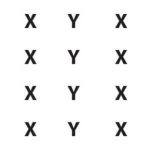

| Similarity | Stimuli that are similar to each other tend to be grouped together. | You are more likely to see three similar columns among the XYX characters at right than you are to see four rows. |  |

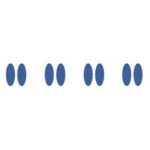

| Proximity | We tend to group nearby figures together. | Do you see four or eight images at right? Principles of proximity suggest that you might see only four. |  |

| Continuity | We tend to perceive stimuli in smooth, continuous ways rather than in more discontinuous ways. | At right, most people see a line of dots that moves from the lower left to the upper right, rather than a line that moves from the left and then suddenly turns down. The principle of continuity leads us to see most lines as following the smoothest possible path. |  |

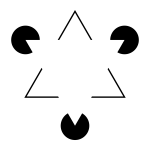

| Closure | We tend to fill in gaps in an incomplete image to create a complete, whole object. | Closure leads us to see a single spherical object at right rather than a set of unrelated cones. |  |

Note: “Summary of Gestalt Principles of Form Perception” by J. A. Cummings & L. Sanders, Introduction to Psychology is used under a CC BY-NC-SA licence

Gestalt Principles and Perceptual Hypotheses

Gestalt theorists explain that pattern perception, which is our ability to differentiate figures and shapes, follows specific principles like closure, proximity, and similarity. These principles guide how we organise sensory information into meaningful wholes. However, our perception does not always match reality.

Gestalt theorists argue that perception is guided by perceptual hypotheses, where our brains make educated guesses when interpreting sensory information. These hypotheses are shaped by our personalities, experiences, and expectations and help us generate a perceptual set (a mental framework for interpreting sensory input). For example, research has shown that verbal priming can bias how people interpret ambiguous figures, demonstrating how our expectations influence what we perceive (Goolkasian & Woodbury, 2010, as cited in Stevens & Stamp).

The Depths of Perception: Bias, Prejudice, and Cultural Factors

Perception is a complex process, influenced by sensations as well as personal experiences, biases, prejudices, and cultural backgrounds. These factors can lead to significant differences in perception between individuals. Research has revealed that implicit biases, such as racial prejudice, can significantly impact perception.

For example:

- Studies have shown that non-Black participants are quicker to identify objects as weapons, and more likely to misidentify non-weapons as weapons, when those objects are paired with images of Black individuals (Payne, 2001; Payne, Shimizu, & Jacoby, 2005, as cited in Stevens & Stamp, 2020).

- Similarly, in video game studies, White participants made decisions to shoot armed targets more quickly when the targets were Black, compared to non-Black targets (Correll, Park, Judd, & Wittenbrink, 2002; Correll, Urland, & Ito, 2006, as cited in Stevens & Stamp, 2020).

This research has troubling implications, particularly when considering the many high-profile cases in recent decades involving young people of colour being killed by individuals who believed, often mistakenly, that these unarmed individuals posed a threat or were armed. Understanding how biases and cultural factors shape perception is essential for addressing these issues and fostering critical thinking.

Naïve Realism

Our perceptual systems function much like an augmented reality system, honed by millions of years of evolution. Long before modern technology created games like Pokémon GO, our brains were augmenting reality to help us interpret and navigate the world. While this system is a remarkable evolutionary achievement, it can lead to errors when our perceptions do not align with what is actually “out there”.

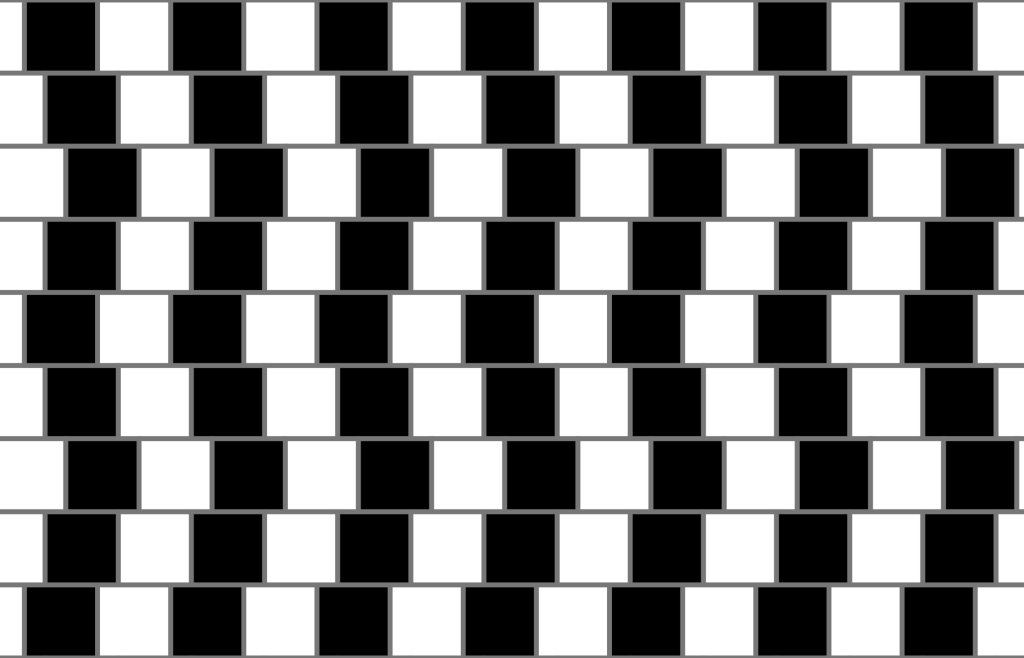

One clear and entertaining way to observe this is through perceptual illusions. For example, in the centre of Figure 4.1.2, you might see a downward-pointing white triangle. However, this triangle does not exist, it is your brain’s top-down processing creating an illusion. Similarly, in Figure 4.1.3, you may see slanted horizontal lines, but there are none; the lines are perfectly straight and parallel. Once again, your perceptual system has augmented reality, creating an experience that does not match objective reality.

Without a healthy dose of science, psychology, and philosophy, many people have a commonsense view of perception that is overly trusting. We tend to place too much faith in our senses, despite their numerous flaws. This perspective is sometimes compared to that of a trusting lover who repeatedly falls for the same lies, only to be betrayed again. In philosophy and psychology, a version of this overly trusting perspective is known as naïve realism.

What is Naïve Realism?

Naïve realism is the belief that everyday objects, like desks, trees, or rain, exist as they appear to us (the “realism” part) and that our senses give us direct and accurate access to these objects (the “naïve” part). According to this view, as we move through the world and interact with objects, they make contact with our sensory systems (like our eye retinas and eardrums), and we perceive them exactly as they are.

This commonsense perspective is practical for navigating daily life. After all, it would be exhausting and unproductive to constantly doubt what your senses show you. However, naïve realism has its limitations. Our sensory systems are far from infallible and leave us vulnerable to misperceptions and errors.

References

Feldman Barrett, L. (2017). How emotions are made: The secret life of the brain. Pan Macmillan.

Stevens, L. & Stamp, J. (2020). Introduction to psychology & neuroscience (2nd ed.). Dalhousie University. https://caul-cbua.pressbooks.pub/intropsychneuro/

Chapter Attribution

Content adapted, with editorial changes, from:

Neuroscience, psychology and conflict management (2024) by Judith Rafferty, James Cook University, is used under a CC BY-NC licence.