5.1. Knowledge

By Michael Ireland, adapted by Marc Chao and Muhamad Alif Bin Ibrahim

The question, “What is knowledge?” has been a central topic in philosophy for centuries. Plato’s dialogue, Theaetetus, represents one of the earliest and most influential attempts to define knowledge. While defining knowledge remains a contentious issue among philosophers, one widely discussed definition is Plato’s concept of knowledge as “justified true belief”, which is often referred to as the JTB definition. According to this view, for someone to claim knowledge, three conditions must be met: the belief must be justified, it must be true, and the individual must believe it. However, as we will see, meeting these conditions is not as straightforward as it might initially seem.

Understanding Belief, Truth, and Justification

Belief is a personal stance or commitment to a proposition about the world. For example, believing that exercise improves mental health is a personal endorsement of that claim. Truth, on the other hand, is more complex because certainty about the truth of many claims is often unattainable. Justification becomes the bridge between belief and truth; it is the reasoning and evidence that support a belief.

The three elements, justification, truth, and belief are closely interwoven. For example, our ability to determine the truth of a belief largely depends on whether we have sufficient justification. Without justification, most people would not consider a belief valid, let alone true.

The distinction between belief and knowledge is crucial. Belief alone is not enough to constitute knowledge. Imagine someone saying, “I don’t know how the magician performs that trick, but I believe he uses mirrors.” Here, belief represents a personal assumption, while knowledge implies a stronger sense of certainty backed by evidence.

To know something, you must also believe it. For example, if research shows that “a positive attitude toward behaviour increases the likelihood of performing that behaviour”, but you refuse to believe this claim, you cannot be said to know it, even though it is true. Similarly, you cannot know something that is not true. If you believe that “a positive attitude has no effect on behaviour”, your belief is simply incorrect, not knowledge.

Four Overlapping Categories

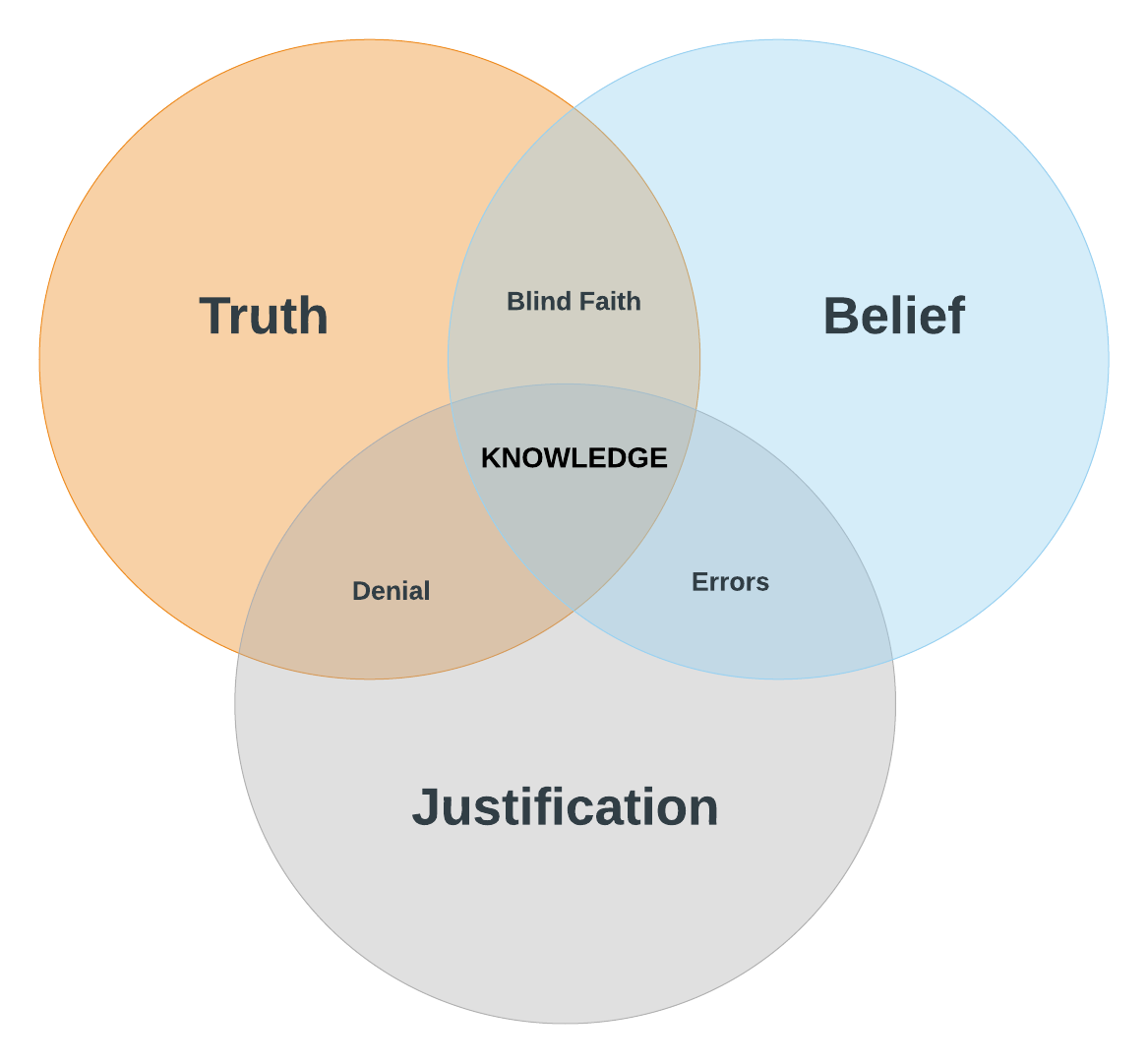

The relationship between belief, justification, and truth creates different scenarios:

- Blind Faith: Beliefs held without sufficient justification.

- Denial: True claims that are rejected despite justification.

- Errors: Beliefs that are held but are ultimately false.

- Knowledge: Beliefs that are both true and well-justified.

Understanding how these categories overlap helps clarify what separates knowledge from mere belief or error (Figure 5.1.1).

The Challenge of Justification

The most difficult part of the justified true belief model is the justification component. How do we justify our beliefs in a way that transforms them into knowledge? In essence, justified beliefs are conclusions supported by solid reasoning and evidence.

To evaluate whether a belief is justified, we rely on arguments. An argument consists of a conclusion supported by premises (reasons or evidence). To assess justification:

- Identify the conclusion: What is the main point the argument is trying to prove?

- Identify the premises: Ask yourself questions like, “Why is this conclusion believed?” or “What evidence supports this conclusion?”

- Evaluate clarity and strength: If the premises are unclear or unsupported, you are not obligated to accept the conclusion.

Different claims require different types of justifications. For example, a scientific claim might need empirical evidence, while a mathematical claim requires logical proof. Understanding how justification works across different domains is key to distinguishing genuine knowledge from unfounded belief.

Uses of the Term ‘Knowledge’

The word knowledge can mean different things depending on how it is used. Broadly speaking, there are three main types: procedural knowledge, acquaintance knowledge, and propositional knowledge.

- Procedural knowledge refers to knowing how to do something, like baking a cake or changing a car battery. It involves skills or abilities rather than facts or information.

Acquaintance knowledge is about familiarity. You might know a person, a city like Brisbane, or your local neighbourhood. It is not about knowing facts but about having personal experience or familiarity with something. - Propositional knowledge is the focus of this section. It refers to knowing that something is true. For example, knowing that water boils at 100°C at sea level or the Earth orbits the Sun. This type of knowledge is expressed through propositions, which are declarative statements about facts or states of affairs.

Propositions and Justification

We first discussed propositions in Chapter 2. To recap, a proposition is a declarative statement that makes a claim about the world, such as “The sky is blue” or “Water is made up of hydrogen and oxygen”. Different types of propositions require different types of justification to support them.

Two important categories of propositions are analytic and synthetic propositions:

- Analytic propositions are primarily found in mathematics and logic. They are true by definition, such as “All bachelors are unmarried men”.

- Synthetic propositions are more common in everyday life and scientific studies, including psychology. They are based on observation and experience, such as “Regular exercise improves mental health”.

Because psychology and many health sciences rely heavily on synthetic propositions, they depend on empirical evidence for justification.

What Does ‘Empirical’ Mean?

The term empirical refers to knowledge gained through sense experience, what we can see, hear, smell, taste, or touch. In scientific research, empirical evidence comes from observations, surveys, experiments, or data collection. When you hear the word empirical, think of observation, but remember that it includes all sensory data, not just what can be visually observed.

For example:

- Scientists might collect empirical data by watching animal behaviour in a natural habitat.

- Psychologists might survey people about their emotional experiences.

Empirical justification uses these sensory experiences as evidence to support a proposition. This contrasts with rational justification, which relies on logic, reasoning, and theoretical frameworks rather than direct observation.

The Relationship Between Empirical and Theoretical Knowledge

Knowledge is not just about collecting raw data from our senses, nor is it purely about abstract reasoning. It emerges from the interaction between empirical observation and rational thought. These two forms of justification depend on each other:

- Empirical evidence (sense experience) provides the raw material for knowledge.

- Rational thought (concepts and theories) processes, organises, and interprets that raw material to make it meaningful.

Without rational thought, sensory data would be chaotic and meaningless. Without sensory input, rational thought would be ungrounded and speculative. The philosopher Immanuel Kant captured this balance perfectly when he explained that all knowledge begins with sensory experience, moves through understanding, and ultimately culminates in reason. For Kant, reason is the highest form of knowledge.

He emphasised that sense experience, which he referred to as intuition, and rational thought, which involves concepts and theories, must work together to produce knowledge. In his words, “Thoughts without content are empty; intuitions without concepts are blind. The understanding can intuit nothing, the senses can think nothing. Only through their union can knowledge arise.”

In essence, empirical observation provides the raw material for knowledge, while rational reasoning organises and interprets that material into meaningful conclusions. Only when these two elements work together can we form a coherent and reliable understanding of the world.

Facts and Knowledge

Facts are statements about the world that we consider to be true. In essence, a fact is a proposition, or an assertion or claim, that has been sufficiently justified with evidence to make it highly unlikely for a reasonable person to reject it. When a proposition meets this standard of justification, it earns the status of a “fact”. For example, if ample evidence supports the claim that water boils at 100°C at sea level, we consider it a fact because it has been repeatedly observed and verified.

However, it is important to note that facts are not merely personal opinions or subjective beliefs. The process of labelling something as a fact follows established procedures for justification, often agreed upon by a community, like scientists or researchers, using shared standards. Even if a fact later turns out to be incorrect, it was still considered factual at the time because it met the accepted criteria for justification. This means there is no such thing as “alternative facts”, despite public claims to the contrary.

In short, a fact is a proposition that has been sufficiently supported by evidence to be widely accepted as true. It is similar to how earning a degree in psychology requires meeting certain academic criteria; once those criteria are met, you earn the title of “psychologist”.

Not all propositions, however, have achieved this level of justification. A proposition that has not been thoroughly supported yet is often called a hypothesis or conjecture.

A hypothesis is essentially a testable claim about the world. Historically, the term carried a negative connotation. Isaac Newton, for instance, famously said, “I do not feign hypotheses” as a criticism of speculative claims. Today, however, the term hypothesis refers to a tentative explanation for a phenomenon, which can be tested through observation or experimentation.

According to Barnhart (1953), a hypothesis is a single proposition proposed as a potential explanation for an observed event or phenomenon. However, for a hypothesis to be considered scientific, it must be falsifiable. This means it must be possible, in principle, to prove the hypothesis wrong through empirical observation or logical reasoning. If a claim cannot be tested or disproven, it does not qualify as a scientific hypothesis.

References

Barnhart, C. L. (Ed.). (1953). The American college dictionary. Harper.

Chapter Attribution

Content adapted, with editorial changes, from:

Mastering thinking: Reasoning, psychology, and scientific methods (2024) by Michael Ireland, University of Southern Queensland, is used under a CC BY-SA licence.