Step 1. Stakeholder engagement (preparatory and ongoing)

Stakeholder engagement

Stakeholder engagement is vitally important in the early stages leading up to, and ongoing throughout implementation of the work. Components of this step include:

- identify key stakeholders

- engage with community leadership early

- ensure community engagement is inclusive and ongoing

- consider cultural factors with engagement

- develop partnerships and community ownership

- engage with a local connector.

Identify key stakeholders

Who are they?

Identifying key stakeholders with a vested interest in health and health care services and engaging them early in the lead up to implementing the co-design planning process is paramount. Each community is unique and key stakeholders in health care planning and delivery will vary.

Key stakeholders are likely to include community leaders, health and community service providers, and community organisations at local and regional levels. Stakeholders may be identified as engagement continues and it’s important to follow new leads as they emerge.

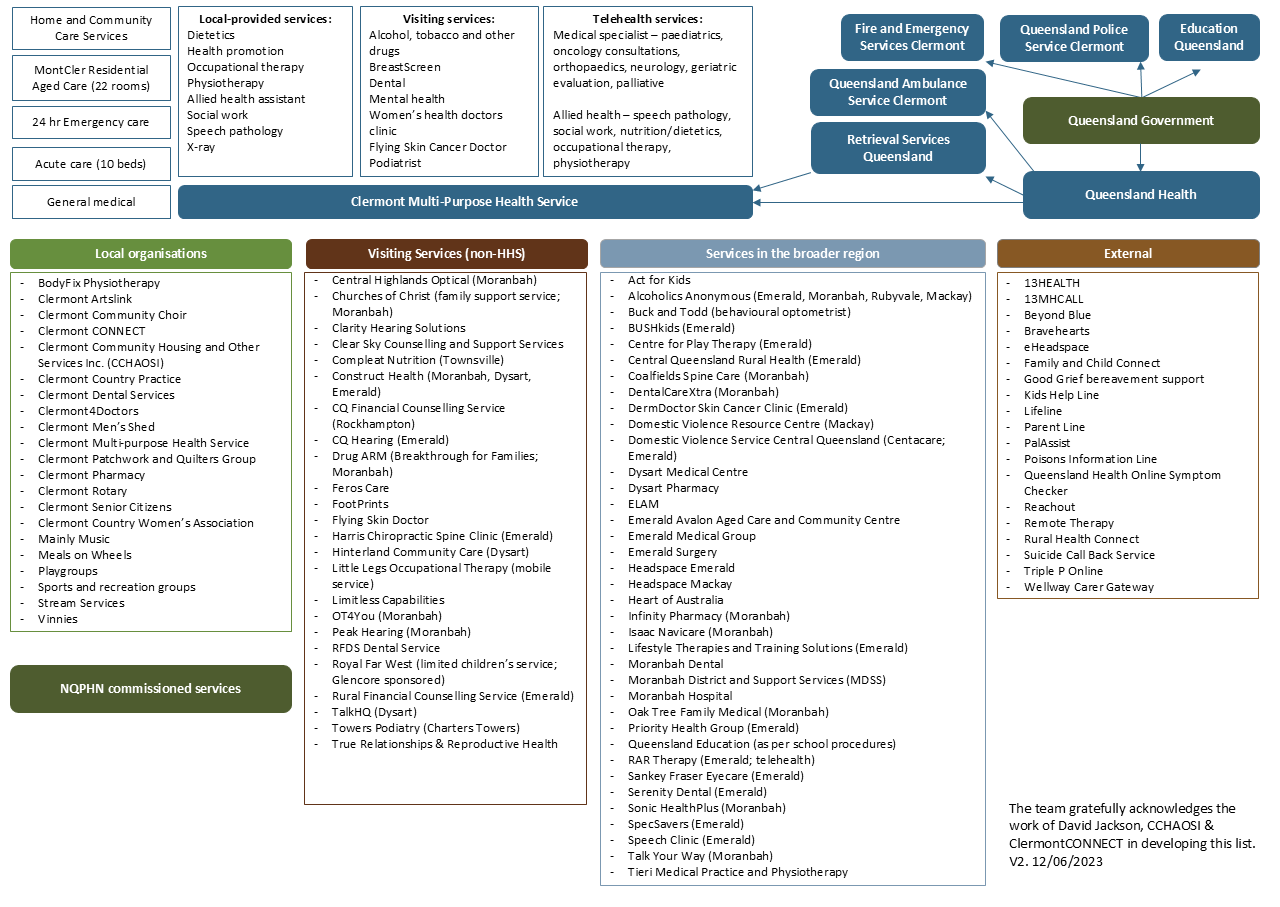

Particularly in small rural and remote communities, a mix of local and visiting health services is common. Try and identify all health professionals (private and public) who may visit the community. In addition, government departments at the state and federal level often have regional representatives who hold responsibility for delivery of government-funded services and programs in these communities (e.g., NDIS, My Aged Care). It may help to visually portray organisations and groups in the community in a stakeholder map (include other services and groups which might also be useful as communication channels). An example of a map for the Clermont community is presented in Figure 4.1.1. Stakeholder mapping may help to understand the relationships and networks within the community and it is important to note that some stakeholders may have a perceived or real level of influence that may inform and/or impact on how the work progresses.

Questions to ask!

Who are the local community? What groups are there? Consider social, cultural, industrial, sporting, etc.

Are there local champions who represent sections of the community? Be mindful that such champions may not represent the interests of all in their group.

What local organisations are present? Examples include individuals, families and local groups, local and regional hospital and health service staff, primary health network, public and private general practitioners, primary health care services, social and community services.

How to seek out stakeholders?

In addition to targeting the more obvious key stakeholders, conduct broad advertising and promotion of the project, its aims and planned co-design activities to increase awareness throughout the community and invite individuals and groups to be involved. Whilst email communication is useful in providing details, conversations with stakeholders both virtually and in person offer the opportunity to discuss aspects of the process and local contextual factors in more detail. Posters and flyers may help raise awareness of the work and facilitate those interested in being involved coming forward. Attendance at local community events can also help in promotion of the work (Figure 4.1.2).

Welcome all stakeholders who are interested and determine how they want to be involved. For example, some members may wish to be active participants, and others simply kept informed of progress and outcomes. Keep a record of all individuals, groups and agencies and their contact details and how they will be involved.

The development of a stakeholder engagement plan may assist in taking a strategic approach to identifying and seeking out stakeholders.

Appendix 1 – Stakeholder Engagement Plan: provides an example of a plan for the Clermont community.

Listen to our Local Connectors talk about promoting the project and encouraging participation:

Engage with community leadership early

Community leaders include informal community champions, or formal leaders such as leaders of community organisations, local councillors, or health service professionals.

Communities often have a range of services that support different groups, so it’s important to engage all relevant services early in the project. Clearly communicate how they can get involved. Focus on promoting social inclusion—for example, by considering gender, disability, age, and cultural diversity.

Discuss the proposal with key community leaders to understand timing and willingness to engage with the work, and gain support.

Ensure community engagement is inclusive

Information about the project, involvement and expected outcomes should be clearly communicated in forms that are accessible to all in the community. This could include existing local and regional networks, local newsletters or papers, community groups, social media, events and posters and flyers in common gathering places (Figure 4.1.3). Word of mouth through the ‘community grapevine’ has been identified as a key communication strategy to facilitate the promotion of planning work. Meet in places where stakeholders feel comfortable.

Ensure that information about the work and issue is available before planned engagement activities. Clearly identify the options for participant involvement and benefit.

During engagement activities and throughout the work, ensure mutual respect for the language, values, standards, and voice of all. Developing guidelines together early in the work about the “ways we work together” is one effective strategy. Development of such guidelines would include discussion about anticipated differences and resistance, agreement on roles and responsibilities (including those of the facilitators initiating the engagement), and agreed visions of how to recognise conflicting priorities, engage respectfully and share decisions.

Guidance from the local reference group and local connector is essential in informing ways of working together and developing engagement strategies.

Listen to our Hughenden Local Connector talk about community engagement:

Consider cultural factors with engagement

Recognise that there may be separate procedures and approaches for respectfully engaging with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and other culturally and linguistically diverse populations.

Cultural protocols differ across communities. They may involve liaison and discussion with local Aboriginal Shire Councils, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Community Controlled Health Organisations/Services, local Elders or other protocols. It is a core responsibility of the group wishing to engage with a community to ensure they understand and follow protocols.

Develop partnerships and community ownership

Ensure modes of governance that promote local ownership of the work. The formation of a local project reference group consisting of key local and regional health and community stakeholders, including general community members (with inclusivity in mind), to advise and guide the work is important for community ownership. Inclusion of leaders who can effect change on this group will support the implementation of agreed solutions. Figure 4.1.4 depicts the initial meeting of group members for the project in the Clermont community.

An established local group may also be an option, depending on the scope of the group and representativeness of members. Utilising an existing group may help promote sustainability in the longer term. In Hughenden, the Community Advisory Network, a long-running group formed to advise the Hughenden Multi-Purpose Health Service, agreed to take on this role. In Kowanyama, the local interagency group agreed to take on the reference group role for the project.

Develop terms of reference to ensure all participants are clear on the purpose of the group, its responsibilities, how it will operate and the approximate timeframe for the work to be completed.

Meet regularly throughout the project to monitor, for advice and guidance and alter actions where required. Whilst virtual modes enable easier participation, an initial in-person meeting is preferred to develop relationships between members. In-person meetings may also be beneficial at key times throughout the process.

Appendix 2 – Terms of Reference: provides a template for rules and group composition of the governance group.

Engage with a Local Connector

If a local individual or agency is not driving the work, it is recommended that external agencies employ a local person, either directly or through a partnership with a local organisation, to inform and support the work and act as a Local Connector. The role aims to introduce and connect the project team within local networks, communicate with the broader community and encourage participation and support the implementation of planning activities. The Local Connectors also provided local and historical knowledge about the community and promoted understanding of community-based interactions and discussions to the broader team. Through the project, Local Connectors were employed by the university to fulfil these roles (Figure 4.1.5).

Working together with a Local Connector or working in partnership with a community organisation throughout the project builds community ownership. It also ensures that external stakeholders initiating the project understand local interpretations and demonstrates that their commitment to a community is tangible through monetary investment.

Active inclusion of local people to advise, facilitate, implement, and evaluate the work offers two-way learning whereby all parties may, for example: increase knowledge of the community and region; build skills in project management, research and stakeholder engagement; or establish or renew local and regional relationships.

Appendix 3 – Local Connector position description: lists potential accountabilities and selection criteria for a Local Connector role (project support officer).

Listen to our Local Connectors talk about their roles:

Factors influencing engagement and participation

There are many factors that influence involvement in place-based health planning and co-design activities. Factors include:

- timing of the work for the community

- leadership

- experiences of past engagement activities

- existing consultative and participatory mechanisms

- competing priorities.

Timing of the work for the community

Timing of the work should account for ‘planned’ and ‘unplanned’ events.

Planned events can be highly relevant to participatory place-based approaches but may also be a competing priority for engagement activities (e.g., school terms, council planning cycles, and community events such as the annual Show or expos).

Timing work to coincide with or build from other initiatives (locally led projects) or planning cycles (e.g. council and health service budget cycles, organisation health needs assessments cycles) can be an enabler of collaborative planning.

Unplanned events such as tragedies, sorry business and natural disasters will negatively impact community members’ ability and desire to engage with planning work.

Timing is particularly important in small rural and remote communities where many local people may be involved/affected by such unplanned events.

Leadership

Early and continued engagement with local and regional organisations is essential to facilitate change or improvements.

Organisations often have hierarchical reporting lines, and building relationships with managers at multiple levels may be required to obtain support and the appropriate approvals for participation and subsequent implementation of change.

Navigating different processes in different organisations can be time and resource-intensive. But community leaders or champions can assist in driving enthusiasm for place-based planning work and facilitate involvement of harder-to-reach groups.

Experiences of past engagement activities

Rural and remote communities experience numerous, recurring requests for input/consultation by governments, academic and other organisations. Willingness to engage in planning activities will be influenced by past experiences of those interactions.

Awareness of positive and negative experiences of past work should inform approaches and timing of planning activities, with a firm goal of establishing positive, collaborative relationships that can lead to productive, sustainable partnerships.

Building trust will likely be necessary unless pre-existing relationships exist.

Building on existing work acknowledges previous community involvement and may offer early momentum for engagement activities.

Ensuring that outcomes and early impacts of work that involved community members are reported in accessible formats for the general community supports future positive collaboration with the community.

Existing consultative and participatory mechanisms

Understanding existing mechanisms for engagement among community members and/or with external stakeholders, and their strengths and weaknesses for broadening community engagement, is essential.

Existing mechanisms often bring together more powerful and motivated voices in the community. But decisions regarding the appropriateness of those mechanisms for longer-term health service place-based planning should be a shared process amongst the broader community.

Competing priorities

Community stakeholders in rural and remote settings who are most inclined to volunteer to engage and collaborate on projects are often already involved in many community and advocacy activities.

Community members (including local service providers) in these settings often have high social or familial responsibility to others in their community in addition to usual daily activities and workloads.

Participation may vary over time; however, it is important to remain open and receptive to contributions at any stage.