1.2 When Do We Communicate? The Communication Process

Andrea Chute, Sharon Johnston, Brandi Pawliuk (adapted by Brock Cook)

Learning Objectives

- explain the components of the transmission model of communication

- explain the components of the interaction model of communication

- explain the components of the transaction model of communication

- compare and contrast these three models of communication.

Communication is a complex process, and it is difficult to determine where or with whom a communication encounter starts and ends. Models of communication simplify the process by providing a visual representation of the various aspects of a communication encounter. Some models explain communication in more detail than others, but even the most complex model does not recreate what we experience in a momentary communication encounter. However, models still serve a valuable purpose for communication students because they allow us to see specific concepts and steps within the communication process, define communication, and apply it. When you become aware of how communication functions, you can think more deliberately through your communication encounters, which can help you better prepare for future communication and learn from the previous communication. The three communication models are the transmission, interaction, and transaction models.

Although these models of communication differ, they contain some common elements. The transmission model and the interaction model include the following parts: participants, messages, encoding, decoding, and channels. In communication models, the participants are the senders and receivers of messages in a communication encounter. The message is the verbal or nonverbal content conveyed from sender to receiver. For example, when you say “Hello!” to your client, you are sending a message of greeting that the client will receive.

The internal cognitive process that allows participants to send, receive, and understand messages is the encoding and decoding process. Encoding is the process of turning thoughts into communication. As we will learn later, the level of conscious thought that goes into encoding messages varies. Decoding is the process of turning communication into thoughts. For example, you may realise you are hungry and encode the following message to send to your roommate: “I’m hungry. Do you want to get pizza tonight?” As your roommate receives the message, they decode your communication and turn it back into thought to make meaning out of it. Of course, we do not just communicate verbally — we have various options or channels for communication. Encoded messages are sent through a channel, or a sensory route on which a message travels, to the receiver for decoding. While communication can be sent and received using any sensory route (sight, smell, touch, taste, or sound), most communication occurs through visual (sight) and auditory (sound) channels. If your client has earbuds in and is engrossed in a phone call, you may need to get their attention by waving your hands before asking them to end the call.

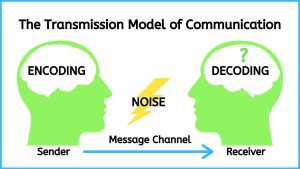

Transmission Model of Communication

The transmission model of communication describes communication as a linear, one-way process in which a sender intentionally transmits a message to a receiver (Adler et al., 2020; Ellis & McClintock, 1990). This model focuses on the sender and the message within a communication encounter. Although the receiver is included in the model, this role is viewed as more of a target or end point rather than part of an ongoing process. We are left to presume that the receiver either successfully receives and understands the message or does not. The scholars who designed this model expanded on a linear model proposed by Aristotle centuries before that included a speaker, message, and hearer. They were also influenced by the advent and spread of new communication technologies such as telegraphy and radio (Shannon & Weaver, 1949); you can probably see these technical influences within the model. Think about how a radio message is sent from a person in the studio to you listening in your car. The sender is the radio announcer who encodes a verbal message transmitted by a radio tower through electromagnetic waves (the channel) and eventually reaches your (the receiver’s) ears via an antenna and speakers to be decoded. The radio announcer does not know if you received his or her message, but if the equipment is working and the channel is free of static, then there is a good chance that the message was successfully received.

Because this model is sender- and message-focused, responsibility is put on the sender to ensure the message is successfully conveyed. This model emphasises clarity and effectiveness but acknowledges barriers to effectively sending communication. Noise is anything that interferes with a message being sent between participants in a communication encounter. Even if a speaker sends a clear message, noise may interfere with a message being accurately received and decoded. The transmission model of communication accounts for environmental and semantic noise.

- Environmental noise is any physical noise present in a communication encounter. Other people talking in a crowded room or hallway could interfere with your ability to transmit a message and have it successfully received and decoded.

- Semantic noise refers to interference in the encoding and decoding process, resulting in different interpretations of what is being communicated (for example, lack of understanding, clarity, and confusion of words and meanings). To use a technical example, a health studies student may tell a client that they should progress their walking time to 60 minutes daily. However, the client’s interpretation of this could be influenced by uncertainty surrounding how fast to walk, how quickly to progress to 60 minutes per day, and whether these 60 minutes should occur simultaneously.

Health Studies Example

A client is seeking care for a suspected urinary tract infection. A healthcare worker communicates to the client that they must provide a urine sample and fully empty their bladder. The healthcare worker speaks quietly to maintain confidentiality because the client is sitting near a waiting room full of people. The client provides a urine sample but does not follow the proper sample collection technique.

Analysis: In this case, the message was successfully sent to the client, as evidenced by the client’s action and response to the request. The interference of environmental noise (healthcare worker speaking softly) and semantic noise (healthcare worker not providing complete instructions) affected how the message was decoded and, ultimately, the accuracy of the urine sample results.

Pros: This model spotlights the sender and the possible noise affecting communication transmission.

Cons: This model is limited because it privileges how the sender communicates, with little attention paid to how the message is received. It is also limited in terms of the message because it simply evaluates whether or not it was delivered. The example above illuminates how detail and nuance should be addressed when communicating.

Although the transmission model may seem simple or even underdeveloped to us today, the creation of this model allowed scholars to examine the communication process in new ways, eventually leading to more complex models and theories of communication that we will discuss later. This model is not quite rich enough to capture dynamic face-to-face interactions, but there are instances in which communication is one-way and linear, especially computer-mediated communication (CMC). This is integrated into many aspects of our lives now, and while it has opened up new ways of communicating, it has also brought some new challenges. Think of text messaging, for example. The transmission model of communication is well suited for describing the act of text messaging since the sender is not sure that the meaning was effectively conveyed or that the message was received. Noise can also interfere with the transmission of a text message. If you use an abbreviation the receiver does not know, or the phone autocorrects to something completely different than you meant, then semantic noise has interfered with message transmission.

Many of you reading this book probably cannot remember a time without CMC. If that is the case, you are what some scholars call “digital natives.” When you take a moment to think about how, over the past 20 years, CMC has changed how we teach and learn, communicate at work, stay in touch with friends, initiate relationships, search for jobs, manage our money, get our news, and participate in our democracy, it is amazing to think that all of those things used to take place without computers. However, the increasing use of CMC has also raised questions and concerns, even among those of you who are digital natives. Many students are interested in studying the effects of CMC on our personal and professional lives and relationships. This desire to study and question CMC may stem from anxiety about the seeming loss or devaluing of face-to-face (f2f) communication. Aside from concerns about the digital cocoons many of us find ourselves in, CMC has also raised concerns about privacy, cyberbullying, and lack of civility in online interactions.

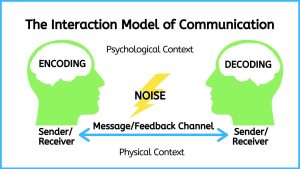

Interaction Model of Communication

The interaction model of communication describes communication as a process in which participants alternate positions as sender and receiver and generate meaning by sending messages and receiving feedback within physical and psychological contexts (Schramm, 1997). Rather than illustrating communication as a linear, one-way process, the interaction model incorporates feedback, making communication more interactive and two-way.

Feedback includes messages sent in response to other messages. For example, your instructor or another student may respond to a point you raise during class discussion. Including a feedback loop also leads to a more complex understanding of the roles of participants in a communication encounter. Rather than having one sender, message, and receiver, this model has two sender-receivers who exchange messages. Each participant alternates roles as sender and receiver to keep a communication encounter going. Although this seems like a perceptible and deliberate process, we quickly alternate between the roles of sender and receiver often without conscious thought.

The interaction model is also less message-focused and more interaction-focused. While the transmission model focuses on how a message is transmitted and whether or not it was received, the interaction model is more concerned with communication. This model acknowledges that so many messages are being sent at one time that many may not even be received. Some messages are also unintentionally sent. Therefore, in this model, communication is not judged effective or ineffective based on whether or not a single message was successfully transmitted and received.

The interaction model takes physical and psychological context into account.

- Physical context includes the environmental factors in a communication encounter. The size, layout, temperature, and lighting of a space influence our communication. Imagine the physical contexts in which client encounters occur and how that may affect your communication. You may attempt to have an emotionally laden discussion with a client in a room where the beds are separated only by curtains. You may be assessing a client in the community where the lighting is dim. Whether the size of the room, the temperature, or other environmental factors, it is important to consider the role physical context plays in communication.

- Psychological context includes the mental and emotional factors in a communication encounter. Stress, anxiety, and emotions are examples of psychological influences that can affect our communication. You may be introducing yourself to one client but worried about another who is grieving or in pain. Alternatively, you may communicate with groups of clients and families experiencing myriad emotions.

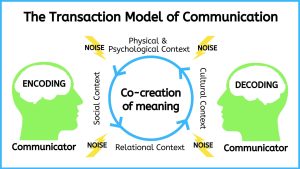

Transaction Model of Communication

As the study of communication progressed, models expanded to account for more of the communication process. Many scholars view communication as more than a process used to carry on conversations and convey meaning. We do not send messages like computers, and we do not neatly alternate between the roles of sender and receiver as an interaction unfolds. We also cannot consciously decide to stop communicating because communication is more than sending and receiving messages. The transaction model differs from the transmission and interaction models in significant ways, including the conceptualisation of communication, the role of sender and receiver, and context (Barnlund, 1970).

The transaction model of communication describes communication as a process in which communicators generate social realities within social, relational, and cultural contexts. In this model, we don’t just communicate to exchange messages; we communicate to:

- create relationships

- form intercultural alliances

- shape our self-concepts

- engage with others in dialogue to create communities.

In short, you do not communicate about your realities; communication helps to construct your realities.

The roles of the sender and receiver in the transaction communication model differ significantly from the other models. Instead of labelling participants as senders and receivers, the people in a communication encounter are called communicators. Unlike the interaction model, which suggests that participants alternate positions as sender and receiver, the transaction model suggests that we are simultaneously senders and receivers.

For example, when you first meet a client, you send verbal messages, saying hello, who you are, and why you are there. Before you finish your introduction, the client is reacting nonverbally. You do not wait until you are done sending your verbal message to start receiving and decoding the nonverbal messages of the client. Instead, you simultaneously send your verbal message and receive the client’s nonverbal messages. This is an important component of this model because it helps you understand how to adapt your communication. For example, in the middle of sending a verbal message, you can adapt your communication in response to the nonverbal message you are simultaneously receiving from your communication partner.

The transaction model also includes a complete understanding of context. The interaction model portrays context as physical and psychological influences that enhance or impede communication. While these contexts are important, they focus on message transmission and reception. Since the transaction model of communication views communication as a force that shapes our realities before and after specific interactions, it must account for contextual influences outside of a single interaction. The transaction model considers how social, relational, and cultural contexts frame and influence our communication encounters.

Here is a short description of each context:

- Social context refers to the stated rules or unstated norms that guide communication. As you are socialised into your area of health studies, you learn communication rules and norms, often called communication strategies, principles, standards, or competencies. Some common rules that influence social contexts in health studies include being truthful during your conversations, being patient and encouraging the client to speak, demonstrating empathy, speaking clearly, active listening, and so on.

- Relational context includes your previous interpersonal history and relationship with a person. You communicate differently with someone you just met versus someone you have known for a long time. Initial interactions with people tend to be more highly scripted and governed by established norms and rules. Within a career in health studies, you should always communicate professionally because the relationship is professional, not personal.

- Cultural context includes aspects of identity such as gender, pronouns, ethnicity, sexual orientation, class, and ability. While you may be able to identify some aspects of the cultural context within a communication encounter, there may also be cultural influences that you cannot see. A competent communicator should not assume they know all the cultural contexts a person brings to an encounter because not all cultural identities are visible. Some people, especially those with identities that have been historically marginalised, are highly aware that their cultural identities influence their communication and influence how others communicate with them. Conversely, people with identities that are dominant or in the majority may rarely, if ever, think about the role their cultural identities play in their communication.

Cultural context can be challenging to manage when it comes to the forefront of a communication encounter. Because intercultural communication creates uncertainty, it can deter people from communicating across cultures or make them view intercultural communication as unfavourable. But if you avoid communicating across cultural identities, you will likely not become more comfortable or competent as a communicator. Intercultural communication has the potential to enrich various aspects of our lives. To communicate well within various cultural contexts, it is important to keep an open mind and avoid making assumptions about others’ cultural identities. As noted, not all cultural identities are visible. While you may readily identify some cultural contexts in a communication encounter, it is important to recognise that there may be other invisible cultural aspects to consider. As with the other contexts, it requires skill to adapt to shifting contexts, and the best way to develop these skills is through practice and reflection.

Each model we have looked at incorporates a different understanding of what communication is and what communication does. The transmission model views communication as a thing, like an information packet, that is sent from one place to another. In this view, communication is defined as sending and receiving messages. The interaction model views communication as an interaction in which a message is sent, followed by a reaction (feedback), another reaction, and so on. In this view, communication produces conversations and interactions within physical and psychological contexts. The transaction model views communication as integrated into our social realities in such a way that it helps us understand them and create and change them.

Watch: Transactional communication [8:50]:

Activity: Check Your Understanding

Summary of Communication Models

The transmission, interaction, and transaction models of communication we have covered are summarised below.

|

Model |

Foci |

|

Transmission Model |

Frames communication as a thing, like an information packet, sent from one place to another. From this perspective, communication is defined as sending and receiving messages. |

|

Interaction Model |

Frames communication as an interaction in which a message is sent, followed by a reaction (feedback), followed by another reaction, and so on. From this perspective, communication is defined as producing conversations and interactions within physical and psychological contexts. |

|

Transaction Model |

Frames communication as integrated into social realities in such a way that it helps communicators understand communications and create and change them. |

Key Takeaways

- Communication models are insufficiently complex to capture all that occurs in a communication encounter. Still, they can help us examine various steps in the process to better understand our communication and the communication of others.

- The transmission model of communication describes communication as a one-way, linear process in which a sender encodes a message and transmits it through a channel to a receiver who decodes it. The transmission of the message may be disrupted by environmental or semantic noise. This model is usually too simple to capture face-to-face interactions but can be usefully applied to computer-mediated communication.

- The interaction model of communication describes communication as a two-way process in which participants alternate positions as sender and receiver and generate meaning by sending and receiving feedback within physical and psychological contexts. This model captures the interactive aspects of communication but still doesn’t account for how communication constructs our realities and is influenced by social and cultural contexts.

- The transaction model of communication describes communication as a process in which communicators generate social realities within social, relational, and cultural contexts. This model includes participants who are simultaneously senders and receivers and accounts for how communication constructs our realities, relationships, and communities.

Exercises

- How might knowing the various components of the communication process help you in your academic, professional, and personal life?

- What communication situations does the transmission model best represent? The interaction model? The transaction model?

- Use the transaction model of communication to analyse a recent communication encounter you had. Sketch out the communication encounter and label each part of the model (communicators, message, channel, feedback, and physical, psychological, social, relational, and cultural contexts).

- Think about the different types of noise that affect communication. List some examples of how noise can worsen communication in personal and professional contexts.

- On a typical day, what types of CMC do you use?

- What are some ways that CMC reduces stress in your life? What are some ways that CMC increases stress in your life? Overall, do you think CMC adds to or reduces your stress more?

- Do you think we, as a society, value face-to-face communication less than we used to? Why or why not?

References

Adler, R. B., Rolls, J. A., & Proctor, R. F. (2020). Looking out, looking in (4th Canadian ed.). Nelson Education.

Barnlund, D. C. (1970). A transactional model of communication. In K. K. Sereno & C. D. Mortensen (Eds.), Foundations of communication theory (pp. 83-92). Harper and Row.

Ellis, R., & McClintock, A. (1990). If you take my meaning: Theory into practice in human communication. Edward Arnold.

Schramm, W. (1997). The beginnings of communication study in America: A personal memoir. SAGE.

Shannon, C., & Weaver, W. (1949). The mathematical theory of communication. University of Illinois Press.

Attribution Statement

With the exception of the healthcare worker example, content adapted, with editorial changes, from:

Chute, A., Johnson, S., & Pawliuk, B. (2023). Professional communication skills for health studies. MacEwan Open Books. https://doi.org/10.31542/b.gm.3. Used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence.

Lapum, J., St.-Amant, O., Hughes, M., & Garmaise-Yee, J. (Eds.). (2020). Introduction to communication in nursing. Toronto Metropolitan University Pressbooks. https://pressbooks.library.ryerson.ca/communicationnursing/. Used under a CC BY-NC 4.0 licence.

University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. (2013). Communication in the real world [Adapted]. https://open.lib.umn.edu/communication/. Used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence.