2.1 All About Self

Andrea Chute, Sharon Johnston, Brandi Pawliuk (adapted by Brock Cook)

Learning Objectives

- explain self-awareness

- explain the components that make up the “self”

- compare and contrast self-concept, self-esteem, and self-efficacy

- describe influences on self-perception

- explain the connection between social penetration, social comparison, and self-disclosure theories

- discuss the process of self-disclosure, including how we make decisions about what, where, when, and how to disclose

- describe impression management and its influence on communication.

If we define ourselves through our actions, what might those actions be, and are we no longer ourselves when we no longer engage in those activities? Psychologist Steven Pinker (2009) defines the conscious present for most people as about three seconds. Everything else is past or future. Who are you now, and will the self you become an hour later be different from the self reading this sentence?

Just as the communication process is dynamic, not static (i.e., constantly changing, not staying the same), you, too, are a dynamic system. Physiologically, your body constantly changes as you inhale and exhale air, digest food, and cleanse waste from each cell. Psychologically you are always in a state of change as well. Some aspects of your personality and character will be constant, while others will shift and adapt to your environment and context. That complex combination contributes to the self you call yourself. We may define self as one’s sense of individuality, personal characteristics, motivations, and actions (McLean, 2005). Still, our definition will fail to capture who we are and who we will become.

To understand our communication interactions with others, we must first understand ourselves. Although each of us experiences ourselves as a singular individual, our sense of self comprises three separate yet integrated components: self-awareness, self-concept, and self-esteem.

Self-Awareness

Self-awareness can be defined in many ways, including “conscious knowledge of one’s character, emotions, values, assumptions, motives, and desires” (Wood et al., 2008). If “awareness” means consciously taking note of the world around us, then self-awareness should mean bringing awareness to yourself.

Self-awareness allows you to see things from others’ perspectives, practice self-control, experience pride in yourself and your work, and have general self-esteem. It also leads to better decision-making, improves personal and professional communication, and enhances self-confidence and competence.

Self-reflection, introspection, mindfulness, or meditation can increase awareness of self and is the primary mechanism to influence personality development. This is the more internally focused form of self-awareness. Self-awareness can also be gained through feedback from other trusted people. This is a more externally focused form of self-awareness. Both forms of knowledge about self are helpful and can lead to many improvements in your life. To embark on a well-balanced journey of self-awareness, consider the following actions:

- Search for yourself – experiment with mindfulness, meditation, and self-reflective practices.

- Share – with those you trust the many parts of yourself, including your ideas, thoughts, feelings, concerns and worries, motivations, and passions.

- Look outside yourself – seek feedback from those you trust who see you in action in various contexts.

- Challenge yourself – as you know more about yourself, your limits and your desires, challenge yourself to step beyond your comfort zone and experience new things. You will discover new things about yourself and grow at the same time.

As you explore self-awareness, you may notice that you can be tough on yourself, overly critical, and perhaps even insecure. Developing a solid sense of yourself is crucial because you monitor your behaviours and form impressions of yourself through self-observation. As you are watching and observing your actions, you are also engaging in social comparison, which is observing and assigning meaning to others’ behaviour and then comparing it with your own. Social comparison has a particularly potent effect on the self when we compare ourselves to those we wish to emulate. The critical point in understanding who you are, what you believe about yourself, how you think you communicate, and how you are shaped by those you interact with begins with awareness of yourself (Beebe et al., 2010).

Self-Concept, Self-Esteem, and Self-Efficacy

Self-Concept

Self-concept refers to the overall idea of who a person thinks they are. If someone said, “Tell me who you are,” your answers would be clues as to how you see yourself and your self-concept. Each person has an overall self-concept that might be encapsulated in a short list of overarching characteristics that they find essential. But each person’s self-concept is also influenced by context, meaning we think differently about ourselves depending on our situation. Sometimes, personal characteristics such as our abilities, personality, and other distinguishing features will best describe who we are. You might consider yourself laid back, traditional, funny, open-minded, or driven, or you might label yourself a leader or a thrill seeker. In other situations, our self-concept may be tied to a group or cultural membership. For example, a student in a U.S. college might consider themselves a Sigma Phi Epsilon fraternity member or a track team member.

Our self-concept is also formed through our interactions with others and their reactions to us. The concept of the looking-glass self explains that we see ourselves reflected in other people’s responses to us and then form our self-concept based on how we believe other people see us (Cooley, 1922). This reflective process of building our self-concept is based on what other people have said, such as “You are a good listener,” and other people’s actions, such as coming to you for advice. These thoughts evoke emotional responses that feed into our self-concept. For example, you may think, “I am glad that people can count on me to listen to their problems.” This is also referred to as reflected appraisal, and the people whose reflections we consider essential are known as significant others.

We also develop our self-concept through comparisons to other people. Social comparison theory states that we describe and evaluate how we compare ourselves to other people. Social comparisons are based on two dimensions: superiority/inferiority and similarity/difference (Hargie, 2011).

In terms of superiority and inferiority, we evaluate characteristics such as attractiveness, intelligence, athletic ability, etc. For example, you may judge yourself to be more intelligent than your brother or less athletic than your best friend, and these judgments are incorporated into your self-concept. This process of comparison and evaluation is not necessarily flawed, but it can have negative consequences if our reference group is inappropriate. We use reference groups for social comparison, which typically change based on our evaluation. Many people choose unreasonable reference groups for social comparison regarding athletic ability. Suppose an individual wants to get into better shape and starts an exercise routine. In that case, they may be discouraged by difficulty keeping up with the aerobics instructor or a running partner and judge themselves as inferior, which could negatively affect their self-concept. Using as a reference group people who have only recently started a fitness program but have shown progress could help maintain a more accurate and hopefully positive self-concept.

We also engage in social comparison based on similarities and differences. Since self-concept is context-specific, similarity may be desirable in some situations and difference more desirable in others. Factors such as age and personality may influence whether or not we want to fit in or stand out. Although we compare ourselves to others throughout our lives, adolescent and teen years usually bring new pressures to be similar to or different from particular reference groups. Think of all the cliques in high school and how people voluntarily and involuntarily broke off into groups based on popularity, interest, culture, or grade level. Some kids in your high school probably wanted to fit in with and be similar to others in the marching band but different from the football players. Conversely, athletes were more apt to compare themselves, in terms of similar athletic ability, to other athletes rather than kids in debate clubs. However, social comparison can be complicated by perceptual influences. As we learned earlier, we organise information based on similarities and differences, but these patterns only sometimes hold true. Even though students involved in athletics and arts may seem very different, a dancer or singer may be very athletic, perhaps even more so than a football team member. There are positive and negative consequences of social comparison.

We generally want to know where we fall in ability and performance compared to others, but what people do with this information and how it affects self-concept varies. Only some people feel they need to be at the top of the list, but some will only stop once they get a high score on a video game or set a new school record in a track-and-field event. Some people strive to be the first chair in the clarinet section of the orchestra, while another person may be content to be the second chair. The education system promotes social comparison through grades and rewards such as honour rolls and dean’s lists. University faculty typically report class aggregate grades, meaning the total number of As, Bs, Cs, etc. This does not violate anyone’s privacy rights but allows students to see where they fell in the distribution. This type of social comparison can be used as motivation. The student who was one of only three out of 23 to get a D on the exam knows that most classmates are performing better than they are, which may lead them to think, “If they can do it, I can do it.” But the social comparison that is not reasoned can have adverse effects and result in negative thoughts like “Look at how bad I did. Man, I am stupid!” These negative thoughts can lead to negative behaviours because we try to maintain internal consistency, meaning we act in ways that match our self-concept. So if the student begins to question their academic abilities and then incorporates an assessment of themselves as a “bad student” into their self-concept, they may behave in ways consistent with that, which will only worsen their academic performance. Additionally, a student might be comforted to learn that they are not the only person who got a D and then not feel the need to try to improve since they have company. You can see in this example that evaluations we place on our self-concept can lead to cycles of thinking and acting. These cycles relate to self-esteem and self-efficacy, which are components of our self-concept.

Self-Concept Components

Self-concept is based on the attitudes, beliefs, and values that you have about yourself. Identity and self-concept are so intertwined that any lasting desired change or improvement becomes difficult (Fiske & Taylor, 1991).

An attitude is your immediate disposition toward a concept or an object. Attitudes can change quickly and frequently. You may prefer vanilla while someone else prefers peppermint, but if that person tries to persuade you how delicious peppermint is, you might be willing to try it and find that you like it better than vanilla.

Beliefs are ideas based on our previous experiences and convictions and may not necessarily be based on logic or fact. You no doubt have beliefs about political, economic, and religious issues. These beliefs may not have been formed through rigorous study, but you hold them as essential aspects of self. Beliefs often serve as a frame of reference through which we interpret our world. Although beliefs can be changed, it usually takes time or robust evidence to persuade someone to change a belief.

Values are core concepts and ideas about what we consider good or bad, right or wrong, or what is worth making a sacrifice for. Our values are central to our self-image, which makes us who we are. Like beliefs, our values may not be based on empirical research or rational thinking, but they are even more resistant to change than are beliefs. A person may need to undergo a transformative life experience to change values.

For example, suppose you highly value the freedom to make personal decisions, including wearing a helmet while driving a motorcycle. This value of individual choice is central to your thinking, and you are unlikely to change this value. However, you might reconsider this value if your brother was driving a motorcycle without a helmet and suffered an accident that fractured his skull and left him with permanent brain damage. While you might still value freedom of choice in many areas of life, you might become an advocate for helmet laws – and perhaps also for other forms of highway safety, such as stiffer penalties for cell phone talking and texting while driving.

Self-Esteem

Self-esteem refers to the judgments and evaluations we make about our self-concept. While self-concept is a broad description of the self, self-esteem is more specifically an evaluation of the self (DeHart & Pelham, 2007). If you were again prompted to “tell me who you are” and then asked to evaluate (label as good/bad, positive/negative, desirable/undesirable) each of the things you listed about yourself, you would reveal clues about your self-esteem. Like self-concept, self-esteem has general and specific elements. Generally, some people are more likely to evaluate themselves positively, while others are more likely to evaluate themselves negatively (DeHart & Pelham, 2007). More specifically, our self-esteem varies across our life span and contexts.

How we judge ourselves affects our communication and behaviours, but not every negative or positive judgment carries the same weight. The negative evaluation of a trait that is not very important for our self-concept will likely not result in a loss of self-esteem. For example, someone may need to improve at drawing. While they appreciate drawing as an art form, they do not consider drawing ability a big part of their self-concept, so if someone critiqued their drawing ability, their self-esteem would not take a big hit. If that person considers themselves a good teacher and has spent considerable time and effort improving their knowledge of teaching and teaching skills, a critique of these would hurt their self-esteem. This does not mean that we cannot be evaluated on something we find important. For example, while teaching is important to faculty members’ self-concept, they are regularly evaluated. Each term, they are reviewed by students, program deans, and colleagues. Most of that feedback is in the form of praise and constructive criticism (which can still be difficult to receive), but when taken in the spirit of self-improvement, it is valuable and may even enhance self-concept and self-esteem. In professional contexts, people with higher self-esteem are more likely to work harder based on negative feedback, are less negatively affected by work stress, can handle workplace conflict better, and can work independently and solve problems (DeHart & Pelham, 2007). Self-esteem is not the only factor contributing to our self-concept; perceptions about our competence also play a role in developing our sense of self.

Self-Efficacy

Self-efficacy refers to people’s judgments about their ability to perform a task within a specific context (Bandura, 1997). Judgments about our self-efficacy influence our self-esteem, which influences our self-concept. The following example illustrates these interconnections.

Pedro did an excellent job on his first college speech. During a meeting with his professor, Pedro indicated he is confident going into the following speech and thinks he will do well. This skill-based assessment indicates that Pedro has a high level of self-efficacy related to public speaking. If he does well, the praise from his classmates and professor will reinforce his self-efficacy and lead him to evaluate his speaking skills, contributing to his self-esteem positively. By the end of the class, Pedro likely thinks of himself as an excellent public speaker, which may become an important part of his self-concept. Throughout these connection points, it is important to remember that self-perception affects how we communicate, behave, and perceive others. Pedro’s increased self-efficacy may give him more confidence in his delivery, which will likely result in positive feedback reinforcing his self-perception. He may start to perceive his professors more positively since they share an interest in public speaking, and he may notice other people’s speaking skills more during class presentations and public lectures. Over time, he may start thinking about changing his major to communication or pursuing career options incorporating public speaking, which would further integrate being “a good public speaker” into his self-concept. You can see that these interconnections can create powerful positive or negative cycles. While some of this process is under our control, much of it is also shaped by the people in our lives.

The verbal and nonverbal feedback we get from people affects our feelings of self-efficacy and our self-esteem. As we saw in Pedro’s example, giving positive feedback can increase our self-efficacy, making us more likely to engage in a similar task in the future (Hargie, 2011). Negative feedback can lead to decreased self-efficacy and a declining interest in engaging with the activity again. People generally adjust their expectations about their abilities based on feedback from others. Positive feedback tends to make people raise their expectations for themselves, and negative feedback does the opposite, ultimately affecting behaviours and creating the cycle. When feedback from others differs from how we view ourselves, additional cycles may develop that impact self-esteem and self-concept.

Self-discrepancy theory states that people have beliefs about and expectations for their actual and potential selves that do not always match up with what they experience (Higgins, 1987). To understand this theory, we must understand the different “selves” that make up our self-concept, which are actual, ideal, and ought selves. The actual self consists of attributes you or someone else believes you possess. The ideal self consists of attributes you or someone else would like you to possess. The ought self consists of the attributes you or someone else believes you should possess. These different selves can conflict with each other in various combinations. Discrepancies between the actual and ideal or ought selves can motivate in some ways and prompt people to act for self-improvement. For example, if your ought self should volunteer more for the local animal shelter, your actual self may be more inclined to do so. Discrepancies between the ideal and ought selves can be incredibly stressful. For example, many professional women who are also mothers have an ideal view of self, including professional success and advancement. They may also have an ought self that includes a sense of duty and obligation to be a full-time mother. The actual self may be someone who does okay at both but does not quite live up to the expectations of either. These discrepancies do not just create cognitive unease – they also lead to emotional, behavioural, and communicative changes.

When we compare the actual self to the expectations of ourselves and others, we can see particular emotional and behavioural effects patterns. When our actual self does not match up with our ideals of self, we are not obtaining our desires and hopes, which can lead to feelings of sadness, including disappointment, dissatisfaction, and frustration. For example, if your ideal self has no credit card debt and your actual self does, you may be frustrated with your lack of financial discipline and be motivated to stick to your budget and pay off your credit card bills.

When our actual self does not match up with other people’s ideals for us, we may not be obtaining significant others’ desires and hopes, which can lead to feelings of sadness, including shame, embarrassment, and concern for losing the affection or approval of others. For example, if a significant other sees you as an “A” student and you obtain a 2.8 GPA in your first year of post-secondary studies, you may be embarrassed to share your grades with that person.

When our actual self does not match what we think other people think we should be, we are not living up to the self that we think others have constructed for us, which can lead to agitation, feeling threatened, and fear of potential punishment. For example, suppose your parents think you should follow in their footsteps and take over the family business, but your actual self wants to enter the military. In that case, you may be unsure of what to do and fear being isolated from the family. Finally, when our actual self does not match up with what we think we should be, we are not meeting what we see as our duties or obligations, which can lead to feelings of agitation, including guilt, weakness, and a feeling that we have fallen short of our moral standard (Higgins, 1987). The following is a review of the four potential discrepancies between selves:

- Actual versus own ideals. We feel we are not obtaining our desires and hopes, leading to disappointment, dissatisfaction, and frustration.

- Actual versus others’ ideals. We have an overall feeling that we are not obtaining significant others’ desires and hopes for us, which leads to feelings of shame and

embarrassment. - Actual versus others’ ought. We feel that we are not meeting what others see as our duties and obligations, leading to agitation, including fear of potential punishment.

- Actual versus own ought. We feel that we are not meeting our duties and obligations, which can lead to a feeling that we have fallen short of our moral standards.

Influences on Self-Perception

We have already learned that other people influence our self-concept and self-esteem. While interactions with individuals and groups are important to consider, we must also note the influence that larger, more systemic forces have on our self-perception. Social and family influences, culture, and the media all shape who we think we are and how we feel about ourselves. Although these are powerful socialising forces, there are ways to maintain some control over our self-perception

Social and Family Influences

Various forces help socialise us into our social and cultural groups and play a powerful role in presenting us with options about who we can be. While we may like to think that our self-perception starts with a blank canvas, our perceptions are limited by our experiences and various social and cultural contexts. Parents and peers shape our self-perceptions in positive and negative ways. The feedback from significant others, including close family, can lead to positive self-views (Hargie, 2011). In the past few years, however, there has been a public discussion and debate about how much positive reinforcement people should give others, especially children. The following questions have been raised: Do we have current and past generations that have been overpraised? Is the praise warranted? What are the positive and negative effects of praise? What is the end goal of the praise? Let’s briefly look at this discussion and its connection to self-perception.

Whether praise is warranted or not is subjective and specific to each person and context, but questions have been raised about the potential adverse effects of too much praise. Motivation is the underlying force that drives us to do things. Sometimes we are intrinsically motivated, meaning we want to do something for the love of doing it or for the resulting internal satisfaction. Other times we are extrinsically motivated, meaning we do something to receive a reward or avoid punishment. If you put effort into completing a short documentary for a class because you love filmmaking and editing, you have been motivated mainly by intrinsic forces. If you complete the documentary because you want an “A” and know that if you fail, your parents will not give you money for your spring break trip, you are motivated by extrinsic factors. Both can, of course, effectively motivate us. Praise is a form of extrinsic reward. Some people speculate that intrinsic motivation will suffer if an actual reward is associated with praise, such as money or special recognition. But what is so good about intrinsic motivation? Intrinsic motivation is more substantial and long-lasting than extrinsic motivation and can lead to developing a work ethic and a sense of pride in one’s abilities. Intrinsic motivation can motivate people to accomplish great things over long periods and be happy despite the effort and sacrifices. Extrinsic motivation dies when the reward stops. Additionally, too much praise can lead people to have a misguided sense of their abilities. College professors who are reluctant to fail students who produce failing work may be setting those students up to be shocked when their supervisor critiques their abilities or output once they are in a professional context (Hargie, 2011).

There are cultural differences in the amount of praise and positive feedback teachers and parents give their children. For example, teachers provide less positive reinforcement in Japanese and Taiwanese classrooms than in Australian classrooms. Chinese and Kenyan parents do not regularly praise their children because they fear it may make them too individualistic, rude, or arrogant (Wierzbicka, 2004). So the phenomenon of overpraising is not universal, and the debate over its potential effects is unresolved.

Research has also found that communication patterns develop between parents and children that are common to many verbally and physically abusive relationships. Such patterns negatively affect a child’s self-efficacy and self-esteem (Morgan & Wilson, 2007). As you will recall, attributions are links we make to identify the cause of a behaviour. Aggressive or abusive parents cannot distinguish between mistakes and intentional behaviours, often seeing honest mistakes as intended and reacting negatively to the child. Such parents also communicate generally negative evaluations to their children by saying, for example, “You cannot do anything right!” or “You are a bad child.” When children exhibit positive behaviours, abusive parents are more likely to use external attributions that diminish the child’s achievement by saying, for example, “You only won because the other team was off their game.” In general, abusive parents have unpredictable reactions to their children’s positive and negative behaviour, which creates an uncertain and often scary climate for a child that can lead to lower self-esteem and erratic or aggressive behaviour. The cycles of praise and blame are just two examples of how the family as a socialising force can influence our self-perceptions.

Culture

How people perceive themselves varies across cultures. For example, many cultures exhibit a phenomenon known as the self-enhancement bias, meaning that we tend to emphasise our desirable qualities relative to other people (Loughnan et al., 2011). However, the degree to which people engage in self-enhancement varies. A review of many studies in this area found that people in Western countries such as Australia and the United States were significantly more likely to self-enhance than people in countries such as Japan. Many scholars explain this variation using a standard measure of cultural variation that claims people in individualistic cultures are more likely to engage in competition and openly praise accomplishments than people in collectivistic cultures. The difference in self-enhancement has also been tied to economics, with scholars arguing that people in countries with greater income inequality are more likely to view themselves as superior to others or want to be perceived as superior to others (even if they do not have economic wealth) to conform to the country’s values and norms. This holds true because countries with high levels of economic inequality, such as Australia and the United States, typically value competition and the right to boast about winning or succeeding. In contrast, countries with more economic equality, such as Japan, have a cultural norm of modesty (Loughnan et al., 2007).

In Australia, cultural identity significantly influences self-perception, particularly among adolescents. For instance, studies suggest that Indigenous Australian girls generally exhibit higher levels of self-esteem and self-assurance compared to their non-Indigenous counterparts. The intricacies of self-perception are further heightened in the context of mixed heritage, notably for individuals born to Indigenous and non-Indigenous parents. These biracial individuals often face the complex task of reconciling and embracing their dual heritage, navigating the complexities of diverse, and sometimes conflicting, cultural norms and expectations. Many biracial individuals, particularly those who are perceived and identify as Indigenous, may find a sense of belonging and positive self-perception within Indigenous communities. These communities can provide a supportive environment, offering protection against racism and reinforcing a positive cultural identity. However, this can sometimes lead to a detachment from their non-Indigenous heritage. In contrast, growing up in predominantly non-Indigenous environments can lead biracial individuals to internalise negative stereotypes about Indigenous Australians, potentially fostering feelings of inferiority. Gender further complicates these dynamics, as biracial men and women may face distinct challenges based on societal expectations and cultural stereotypes, impacting their occupational aspirations and acceptance of their physical features, respectively. Navigating these multifaceted cultural identities often places biracial individuals at the margins of both communities, posing significant challenges to the development of a robust and positive self-concept and self-esteem.

Some general differences in gender and self-perception relate to self-concept, self-efficacy, and envisioning ideal selves. As with any cultural differences, these are generalisations supported by research but do not represent all individuals within a group. Regarding self-concept, men are more likely to describe themselves regarding their group membership, and women are more likely to include references to relationships in their self-descriptions. For example, a man may note that he is a boat enthusiast or a member of the Rotary Club, and a woman may note that she is a mother of two or a loyal friend.

Regarding self-efficacy, men tend to have higher perceptions of self-efficacy than women (Bowles, 1993). In terms of actual and ideal selves, men and women in a variety of countries both described their ideal selves as more masculine (Best & Thomas, 2004). Gender differences are interesting to study but are often exaggerated beyond the actual variations. Socialisation and internalisation of societal norms for gender differences account for much more of our perceived differences than innate or natural differences between genders. These gender norms may be explicitly stated — for example, a mother may say to her son, “Boys do not play with dolls,” or they may be more implicit, with girls being encouraged to pursue historically feminine professions such as teaching or nursing without others stating the expectation.

Media

The representations we see in the media affect our self-perception. The vast majority of media images include idealised representations of attractiveness. Even though the images of people we see in glossy magazines and on movie screens are not typically what we see when we look at the people around us in a classroom, at work or the grocery store, many of us continue to hold ourselves to an unrealistic standard of beauty and attractiveness. Movies, magazines, and television shows are filled with beautiful people, and less attractive actors (when present in the media) are typically portrayed as the butt of jokes, villains, or only as background extras (Patzer, 2008). Aside from overall attractiveness, the media also offers narrow representations of acceptable body weight. Researchers have found that only 12 percent of prime-time characters are overweight, which is dramatically less than the national statistics for obesity among the actual population (Patzer, 2008). Further, an analysis of how weight is discussed on prime-time sitcoms found that heavier female characters were often the targets of negative comments and jokes that audience members responded to with laughter. Conversely, positive comments about women’s bodies were related to their thinness. In short, the heavier the character, the more negative the comments, and the thinner the character, the more positive the comments. The same researchers analysed sitcoms for content regarding male characters’ weight. They found that although comments were made, they were fewer in number and not as harmful, ultimately supporting the notion that overweight male characters are more accepted in media than overweight female characters. In recent years, much more attention has been paid to the potential negative effects of such narrow media representations.

Regarding self-concept, media representations guide us on what is acceptable, unacceptable, or not valued in our society. Mediated messages reinforce cultural stereotypes about race, gender, age, sexual orientation, ability, and class. People from historically marginalised groups must look much harder than dominant groups to find positive representations of their identities in media. As a critical thinker, it is essential to question media messages and examine who is included and excluded. Advertising, in particular, encourages people to engage in social comparison, regularly communicating that we are inferior because we lack a certain product or that we need to change some aspect of our lives to keep up with and be similar to others. For example, for many years, advertising targeted to women instilled in them a fear of having a dirty house, selling them products that promised to keep their home clean, make their family happy, and impress their friends and neighbours. Now messages tell us to fear becoming old or unattractive, selling products to keep our skin tight and clear, which will, in turn, make us happy and popular.

Beware of Self-fulfilling Prophecy

A self-fulfilling prophecy occurs when your expectation causes something to happen. Suppose your colleagues tell you that there is a new staff member that started last week. When you ask them what they thought of the new staff member, they describe the person as aloof and rude.

Later in the day, you run into a new staff member. Based on the description you heard from your colleagues, you say “Excuse me” in an aggressive manner and push your way into the space. The new staff member gives you a harsh look and leaves quickly. The next time you see your friends, tell them you met the new staff member and agree with their assessment.

Was your new staff member aloof and rude? Or did you treat the new staff member so that your preconceived notion would be fulfilled? If so, it is a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Sometimes our expectations (or the expectations of others) can influence our communication behaviours. In the example above, the information you received from your colleagues affected how you interacted with the new staff member. How might things have been different if you knew nothing about the new staff member before you met? Would you have communicated in a friendlier manner? If you had, would the new staff member react differently? It is difficult to say what would have happened, but it is important to remember that the feedback we receive about others may not be accurate. We may create a self-fulfilling prophecy if we communicate with others based on inaccurate information.

Self-Disclosure and Interpersonal Communication

Have you ever said too much on a first date? At a job interview? To a professor? Have you ever posted something on social media only to return to it later to remove it? When self-disclosure works out well, it can positively affect interpersonal relationships. Conversely, self-disclosure that does not work out well can lead to embarrassment, lower self-esteem, and relationship deterioration or even termination. As with all other types of communication, increasing your competence regarding self-disclosure can have many positive effects.

So what is self-disclosure? It could be argued that verbal or nonverbal communication reveals something about the self. The clothes we wear, a laugh, or an order at the drive-through may offer glimpses into our personality or past, but they are not necessarily self-disclosure. Self-disclosure is the purposeful disclosure of personal information to another person. If someone purposefully wears the baseball cap of their favourite team to reveal their team loyalty to a new friend, this clothing choice constitutes self-disclosure. Self-disclosure does not always have to be deep to be useful or meaningful. Superficial self-disclosure, often in the form of “small talk,” is key in initiating relationships that move to more personal levels of self-disclosure. Telling a classmate your major or your hometown during the first week of school carries relatively little risk but can build into a friendship that lasts beyond the class.

Self-Disclosure Theories

Social penetration theory states that as we get to know someone, we engage in a reciprocal process of self-disclosure that changes in breadth and depth and affects how a relationship develops. Depth refers to how personal or sensitive the information is, and breadth refers to the topics discussed (Greene et al., 2006). You may recall in the movie Shrek that Shrek declares that “ogres are like onions” (Adamson & Jenson, 2001). While certain circumstances can lead to a rapid increase in the depth or breadth of self-disclosure, social penetration theory states that in most relationships, people gradually penetrate through the layers of each other’s personality like we peel the layers from an onion.

The theory also argues that people in a relationship balance needs that are sometimes in tension, which is a dialectic. Balancing a dialectic is like walking a tightrope. You have to lean to one side and eventually lean to another side to keep yourself balanced and prevent falling. The constant back and forth allows you to stay balanced, even though you may not always be even or standing straight up. One of the critical dialectics that must be negotiated is the tension between openness and closedness (Greene et al., 2006). We want to make ourselves open to others through self-disclosure and maintain a sense of privacy.

We may also engage in self-disclosure for social comparison. Social comparison theory states that we evaluate ourselves based on how we compare with others (Hargie, 2011). We may disclose information about our intellectual aptitude or athletic abilities to see how we relate to others. This type of comparison helps us decide whether we are superior or inferior to others in a particular area. Disclosures about abilities or talents can also lead to self-validation if the person to whom we disclose reacts positively. By disclosing information about our beliefs and values, we can determine if they are the same as or different from others. Last, we may disclose fantasies or thoughts to another to determine whether they are acceptable or unacceptable. We can engage in social comparison as the discloser or the receiver of disclosures, which may allow us to determine whether or not we are interested in pursuing a relationship with another person.

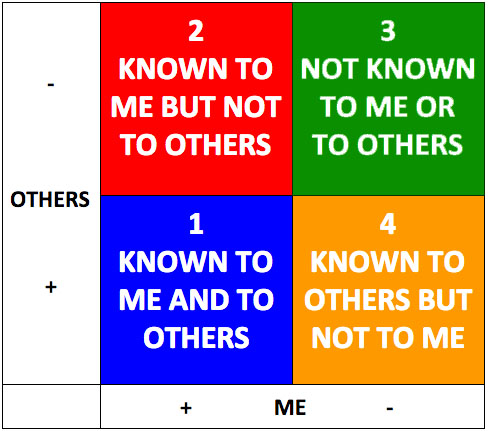

The final theory of self-disclosure that we will discuss is the Johari window,

Who are you? How do you see yourself? How do others see you? You are more than your actions and more than your communication, and the result may be greater than the sum of the parts, but how do you know yourself? For many, these questions can prove challenging as we try to reconcile the self-concept we perceive with what we desire others to perceive about us, as we try to see ourselves through our interactions with others. As we come to terms with the idea that we may not be aware or know everything, there is still much to know about ourselves.

What do we know about ourselves? What aspects of ourselves do we share with others? What aspects of ourselves are yet to be determined? In 1955, psychologists Joseph Luft and Harry Ingham created a model known as the Johari window to visually represent the aspects of self that are known to us versus those unknown. Their model has four quadrants (Figure 2.1.1).

In the first quadrant (lower left-hand corner) are those ideas known to self and others. This quadrant is considered the open area and likely includes concepts like your name, hobbies, and other topics about yourself that you freely share with others. If you have a social media account, the messages you post publicly will fall into this quadrant.

In the second quadrant (upper left-hand corner) are those ideas that are unknown to self but known to others. This quadrant is considered the blind area. This area might be easier to think about in terms of others. Do you have a friend, coworker, or sibling who comes off as abrasive but does not know it? Or maybe you know someone who is a pushover but does not see it. Do you think that their lack of recognition affects their understanding of self? Now, let’s think about it in terms of ourselves. What are our blind spots? These aspects of our personality (that others readily know) but escape our notice fall into this area of the Johari window. Perception checking and soliciting feedback from others can help us learn more about our blind area.

In the third quadrant (upper right-hand corner) are those ideas unknown to self and others. This quadrant is considered an unknown area. This area includes things you and others do not know (yet). How will you cope with the loss of a parent (if both your parents are living)? What type of parent will you be (if you don’t have children)? How successful will your career be (if you are in university and have not started a career yet)? Because these things have not happened yet, the outcome is unknown. To become more self-aware, we must solicit feedback from others to learn more about our blind pane, but we must also explore the unknown pane. To discover the unknown, we must get out of our comfort zones and try new things. We must pay attention to the things that excite or scare us and investigate them more to see if we can learn something new about ourselves. By being more aware of what is contained in these panes and how we can learn more about each one, we can more competently engage in self-disclosure and use this process to enhance our interpersonal relationships.

In the fourth quadrant (lower right-hand corner) are those ideas that are known to self but unknown to others. This quadrant is considered the hidden area and includes things you know about yourself that you do not share with others (i.e., traumas you have experienced, emotional insecurities, embarrassing situations, and so on). As we get to know someone, we self-disclose and move information from the “hidden” to the “known” pane. Doing this decreases the size of our hidden and known areas, increasing our shared reality. The reactions we get from people as we open up to them help us form our self-concepts and also help determine the trajectory of the relationship. If the person reacts favourably to our disclosures and reciprocates disclosure, the disclosure cycle continues, and a deeper connection may be forged.

These dimensions of self remind us that we are not fixed – that freedom to change combined with the ability to reflect, anticipate, plan, and predict allows us to improve, learn, and adapt to our surroundings. By recognising that we are not fixed in our “self” concept, we come to terms with the responsibility and freedom inherent in our potential humanity.

In health studies communication, the self plays a central role. How do you describe yourself? Do your career path, job responsibilities, goals, and aspirations align with what you recognise to be your talents? How you represent “self” through your CV, in your writing, your articulation, and in a presentation – these all play an essential role as you negotiate the relationships and climate present in any organisation.

Understanding your perspective can lend insight into your awareness – the ability to be conscious of events and stimuli. Awareness determines what you pay attention to, how you carry out your intentions, and what you remember of your activities and experiences each day. Awareness is complicated and fascinating, especially how we take in information, give it order, and assign it meaning.

Self-Disclosure and Social Media

Facebook and Instagram are undoubtedly dominating the world of online social networking, and the willingness of many users to self-disclose personal information ranging from moods to religious affiliation, relationship status, and personal contact information has led to an increase in privacy concerns. Facebook and Instagram offer convenient opportunities to stay in touch with friends, family, and coworkers, but are people using them responsibly? Some argue fundamental differences exist between today’s digital natives and older generations, whose private and public selves are intertwined through these technologies. Even though some colleges offer seminars on managing privacy online, we still hear stories of self-disclosure gone wrong, such as the football player from the University of Texas who was kicked off the team for posting racist comments about the president or the student who was kicked out of his private, Christian college after a picture of him dressed in drag surfaced on Facebook. However, social media experts say these cases are rare and that most students know who can see what they are posting and the potential consequences. The issue of privacy management on Facebook affects parent-child relationships, too, and as the website “Oh Crap. My Parents Joined Facebook” shows, the results can sometimes be embarrassing for the student and the parent as they balance the dialectic between openness and closeness once the child has moved away.

The Process of Self-Disclosure

Many decisions go into the process of self-disclosure. We have many types of information we can disclose, but we have to determine whether or not we will proceed with disclosure by considering the situation and the potential risks. Then we must decide when, where, and how to disclose. Since all these decisions affect our relationships, we will examine each in turn.

Four main categories for disclosure include observations, thoughts, feelings, and needs (Hargie, 2011). Observations include what we have done and experienced. For example, someone could tell you they live in a farmhouse in Alberta. If they told you that moving from the city to the country was a good decision, they would share their thoughts because they included a judgment about their experience. Sharing feelings includes expressing an emotion – for example, “I am happy to wake up every morning and look out at the grain fields. I feel lucky.” Last, we may communicate needs or wants by saying, “My best friend is looking for a job, and I want him to move here, too.” We usually begin disclosure with observations and thoughts and then move on to feelings and needs as the relationship progresses. There are some exceptions to this. For example, we are more likely to disclose sincerely in crises, and we may also disclose more than usual with a stranger if we do not think we will meet the person again or do not share social networks. Although we do not often find ourselves in crises, you may recall scenes from movies or television shows where people trapped in an elevator or stranded after a plane crash reveal their deepest feelings and desires. I imagine we have all been in a situation where we said more about ourselves to a stranger than we usually would. To better understand why, let’s discuss factors influencing our disclosure decision.

Generally speaking, some people are naturally more transparent and willing to self-disclose, while others are more opaque and hesitant to reveal personal information (Jourard, 1964). Interestingly, research suggests that the pervasiveness of reality television, much of which includes participants who are very willing to disclose personal information, has led to a general trend among reality television viewers to engage in self-disclosure through other mediated means such as blogging and video sharing (Stefanone & Lackaff, 2009). Whether online or face-to-face, there are other reasons for disclosing or not, including self-focused, other-focused, interpersonal, and situational (Greene et al., 2006).

Self-focused reasons for disclosure include having a sense of relief or catharsis, clarifying or correcting information, or seeking support. Self-focused reasons for not disclosing include fear of rejection and loss of privacy. In other words, we may disclose to get something off our chest in hopes of finding relief, or we may not disclose out of fear that the other person may react negatively to our revelation. Other-focused reasons for disclosure include a sense of responsibility to inform or educate. Other-focused reasons for not disclosing include feeling like the other person will not protect the information. If someone mentions that their car would not start this morning and you disclose that you are good at working on cars, you have disclosed to help the other person. Conversely, you may hold back disclosure about your new relationship from your coworker because they are known to be loose-lipped with other people’s information. Interpersonal reasons for disclosure involve desires to maintain a trusting and intimate relationship. Interpersonal reasons for not disclosing include fear of losing the connection or deeming the information irrelevant to the relationship. Finally, situational causes may include the other person being available, directly asking a question, or being directly involved in or affected by the disclosed information. Situational reasons for not disclosing include the person being unavailable, lacking time to discuss the information thoroughly, or lacking a suitable (i.e., quiet, private) place to talk. For example, finding yourself in a quiet environment where neither person is busy could lead to disclosure, while a house full of company may not.

Deciding when to disclose something in a conversation may not seem as important as determining whether or not to disclose it. However, choosing to disclose and then doing it at an awkward time in a conversation could lead to negative results. Regarding timing, you should consider disclosing the information early, mid, or late in a discussion (Greene et al., 2006). If you get something off your chest early in a conversation, you may ensure plenty of time to discuss the issue and that you do not lose your nerve. If you wait until the middle of the conversation, you have some time to feel the other person’s mood and set up the tone for your disclosure. For example, if you meet up with your roommate to tell her that you’re planning on moving out, and she starts by saying, “I have had the most terrible day!” the tone of the conversation has now shifted, and you may not end up making your disclosure. If you start by asking your roommate how she is doing, and things seem to be going well, you may be more likely to follow through with the disclosure. You may disclose late in a conversation if you are worried about the person’s reaction, if you know they have an appointment, or if you must go to class at a particular time; disclosing just before that time could limit your immediate exposure to any adverse reaction. However, if the person does not react negatively, they could still become upset because they do not have time to discuss the disclosure with you.

Sometimes self-disclosure is unplanned. Someone may ask you a direct question or disclose personal information, which leads you to reciprocate disclosure. In these instances, you may not manage your privacy well because you have not had time to consider any potential risks. In the case of a direct question, you may feel comfortable answering, giving an indirect or general answer, or feeling enough pressure or uncertainty to give a dishonest answer. If someone unexpectedly discloses, you may need to reciprocate by disclosing something personal. If you are uncomfortable doing this, you can still support the other person by listening and giving advice or feedback.

Once you have decided when and where to disclose information to another person, you must figure out the best channel. Face-to-face disclosures may feel more genuine or intimate, given the shared physical presence and ability to receive verbal and nonverbal communication. There is also an opportunity for immediate verbal and nonverbal feedback, such as asking follow-up questions or demonstrating support or encouragement through a hug. The immediacy of a face-to-face encounter also means you have to deal with the uncertainty of the reaction you will get. If the person reacts negatively, you may feel uncomfortable, pressured to stay, or even fearful. You may seem less genuine or personal if you choose a mediated channel such as an email or a letter, text, note, or phone call. Still, you have more control over the situation in that you can take time to choose your words carefully, and you do not have to face the reaction of the other person immediately. This can be beneficial if you fear an adverse or potentially violent reaction. Another disadvantage of choosing a mediated channel is the loss of nonverbal communication which can add many contexts to a conversation. Although our discussion of the choices involved in self-disclosure so far has focused primarily on the discloser, self-disclosure is an interpersonal process that has much to do with the receiver of the disclosure.

Effects of Disclosure on the Relationship

The process of self-disclosure is circular. An individual self-discloses, the disclosure recipient reacts, and the original discloser processes the reaction. The critical elements of the process are how the receiver interprets and responds to the disclosure. Part of the response results from the receiver’s attribution (reason) of the cause of the disclosure, which may include dispositional, situational, and interpersonal attributions (Jiang et al., 2011).

Let’s say your coworker discloses that she thinks the new boss got his promotion because of favouritism instead of merit. You may make a dispositional attribution that connects the cause of her disclosure to her personality by thinking, for example, that she is outgoing, inappropriate for the workplace, or fishing for information. If the personality trait to which you attribute the disclosure is positive, then your reaction to the disclosure is more likely to be positive. Situational attributions identify the cause of a disclosure with the context or surroundings in which it takes place. For example, you may attribute your coworker’s disclosure to the fact that you agreed to go to lunch with her. Interpersonal attributions identify the relationship between the sender and receiver as the cause of the disclosure. So if you attribute your coworker’s comments to the fact that you are best friends at work, you think your unique relationship caused the disclosure. Suppose the receiver’s primary attribution is interpersonal. In that case, relational intimacy and closeness will likely be reinforced more than if the attribution is dispositional or situational because the receiver feels they were specially chosen to receive the information.

The receiver’s role does not end with attribution and response. There may be added burdens if the information shared with you is a secret. As was noted earlier, there are clear risks involved in the self-disclosure of intimate or potentially stigmatising information if the receiver of the disclosure fails to keep that information secure. As the receiver of a secret, you may need to unburden yourself from the co-ownership of the information by sharing it with someone else (Derlega et al., 1993). This is not always a bad thing. You may strategically tell someone who is removed from the social network of the person who told you the secret to keep the information secure. Although unburdening yourself can be a relief, sometimes people tell secrets they were entrusted with keeping for less productive reasons. A research study of office workers found that 77% of workers who received disclosure and were told not to tell anyone else told at least two other people by the end of the day (Hargie, 2011)! They reported doing so to receive attention for having inside information or to demonstrate their power or connection. Spreading someone’s private disclosure without permission for personal gain does not demonstrate communication competence.

When the disclosure cycle goes well for the discloser, there will likely be a greater sense of relational intimacy and self-worth. There are also positive psychological effects, such as reduced stress and increased feelings of social support.

Self-disclosure can also have effects on physical health. Spouses of suicide or accidental death victims who did not disclose information to their friends were more likely to have more health problems, such as weight change and headaches and suffer from more intrusive thoughts about the death than those who did talk with friends (Greene et al., 2006).

Alternatives to Self-Disclosure

So, what techniques can you use if you do not want to self-disclose to others? First, you can use deception. Sometimes people lie to avoid conflict. This is true in cases where the person may become extremely upset. They can lie to gain power or to save face. They can also lie to guide the interaction. Of course, there is also the benevolent lie (sometimes called a “white” lie). This is a lie done to save someone else’s face. It is not done to help oneself but to avoid hurting someone else. Imagine, for example, your grandma bakes you cookies and is so happy she can give them to you, but you do not like them. Do you tell her that or lie and tell her you are glad she made them for you?

Second, you can equivocate. This means you don’t answer the question or give your comments. Instead, you restated what they said differently. For instance, Sally says, “How do you like my new dress?” you can say, “Wow! That’s a new outfit!” In this case, you do not express your feelings or opinions. You only offer the information that has been provided to you.

Third, you can hint. You may not want to lie or equivocate to someone you care about. You might use indirect or face-saving comments. For example, if your roommate has not helped you clean your apartment, you might say things like, “It sure is messy in here,” or “This place could use some cleaning.”

A fourth alternative is silence: simply not saying anything at all.

Impression Management

How we perceive ourselves manifests in how we present ourselves to others. Impression management strategically conceals or reveals personal information to influence others’ perceptions (Human et al., 2012). We engage in this process daily and for different reasons. In his seminal 1959 book, The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, Sociologist Erving Goffman opened up the conversation about impression management, which he called “facework,” with the idea that impression management is about figuring out the “face” you want to present to the world. Goffman also noted that we are all essentially performers on a stage, adjusting our performance to help shape how others see and respond to us.

Although people occasionally intentionally deceive others in managing impressions, we generally try to make a good impression while remaining authentic. Since impression management helps meet our practical, relational, and identity needs, we stand to lose quite a bit if we are caught intentionally misrepresenting ourselves. In May of 2012, Yahoo!’s CEO resigned after it became known that he stated on official documents that he had two college degrees when he only had one. In a similar incident, a woman who had long served as the dean of admissions for the prestigious Massachusetts Institute of Technology was dismissed from her position after it was learned that she had only attended one year of college and had falsely indicated she had a bachelor’s and master’s degree (Webber & Korn, 2012). Such incidents clearly show that although people can get away with such false impression management for a while, the eventual consequences of being found out are dire. As communicators, we sometimes engage in more subtle inauthentic impression management. For example, a person may say they know more about a subject or situation than they do to seem wise or “in the loop.” A speaker works on a polished and competent delivery during a speech to distract from a lack of substantive content. These cases of strategic impression management may never be found out, but communicators should still avoid them as they do not live up to the standards of ethical communication.

Consciously and competently engaging in impression management can benefit us by giving others a more positive and accurate picture of who we are. People skilled in impression management are typically more engaging and confident, allowing others to pick up on cues from which to form impressions (Human et al., 2012). Being a skilled impression manager draws on many practices of competent communicators, including becoming a higher self-monitor. When impression management and self-monitoring skills combine, communicators can simultaneously monitor their expressions, the reactions of others, and the situational and social context (Sosik et al., 2002). Sometimes people get help with their impression management. Although most people can’t afford or would not consider hiring an image consultant, some generously donated their impression management expertise to help others. For example, a project called “Style Me Hired” offered free makeovers to jobless people to offer them new motivation and help them make favourable impressions and hopefully get a job offer.

Characteristics of Impression Management

Based on Goffman’s work, our own experiences, and the research done since Goffman’s time, we can identify a few characteristics of impression management (Adler & Proctor, 2017). For example, we know that we have more than one “face” that we present to the world. For example, you may have one face you use as a student, another as an employee, another as a friend, and so on. At the core of your being, though, you have a sense of who you are and how you perceive yourself, which we know is our self-concept. Of course, there will be elements of your self-concept in the faces you present to the world, but as discussed in the previous disclosure section, you may not choose to share all of who you are with everyone you meet.

Another characteristic relates to Goffman’s comparison to people as performers concerning impression management. As we respond to or attempt to influence how others see us, impression management involves a partnership with those around us. For example, if a person wears a new outfit and no one comments on it, they might think that no one liked it and thus not wear it again. Conversely, if they receive many compliments on the outfit, they may wear it more often and buy other clothes in a similar style. We can also see this happening on social media when people post on their accounts. If the post receives little attention, they might delete it or not post similarly to that again. But if a post is successful, mainly if it goes viral, the person will likely attempt to create similar posts.

Of course, as is true with communication in general, our impression management can be intentional or unintentional. Carefully choosing what to wear for a job interview is a deliberate form of impression management. Not realising the joke you just told was offensive to some people who heard it would be an unintentional form of impression management. This also connects to the Johari Window model, as unintentional impression management would be in the blind area, whereas intentional impression management could be in the open or hidden areas. The hidden area is included because those around you might not be aware of how much effort went into your impression management or how important their impression of you is to you.

Categories of Impression Management

There are three categories of how we manage others’ impressions of us: manner, appearance, and setting (Goffman, 1959).

Manner

Manner refers to our words and actions. The words we choose to use and how we speak them are manners. An example: a person excitedly told a friend about a new book about acting they had read by Uta Hagen. They had only seen the author’s name written, not heard it pronounced, so they said her name as “You-Ta Hāgen.” The friend, who was very kind not to make fun, said, “Oh, I’ve also heard it pronounced, “U-ta Hog-en.” Of course, that pronunciation was correct, but the mispronunciation created an unintentional impression about the speaker, specifically their education level. We will talk more about manners when we look at how we convey meaning through the words we use and how we say them. That includes tone, volume, rate, pronunciation, accent, and emphasis. It also includes our posture, gestures, and distance (including the use of personal space) when we think of actions. All of these convey more than meaning; they also create impressions in the minds of those who perceive our words and our actions.

Appearance

Appearance refers to our clothing and other aspects of our personal appearance. What you wear, how you style your hair, and whether or not you wear makeup are all a part of your appearance and influence how people perceive you.

Appearance conveys more than just a look; it also can convey meaning. For example, wearing a Broncos t-shirt shows that you are a fan of the team.

Sometimes we may not think much about our appearance. Indeed, if students are asked in class about who carefully picked out the outfit they wore to the class that day, there may only be one or two students who raise their hands. But other times, we give a lot of attention to our appearance – a date, for example, or a formal event such as a wedding or graduation. Job interviews are another time when a person carefully dresses for their desired job.

Setting

The setting is how we decorate our homes and offices and refers to the cars we drive. Indeed, the material objects and people surrounding a person influence our perception. The link between environmental cues and perception is important enough that many companies create policies about what can and cannot be displayed in personal office spaces. For example, it would seem odd for a healthcare environment to have a movie poster hanging in a waiting area. This would influence clients’ perceptions of the healthcare provider’s personality and credibility. The arrangement of furniture also creates impressions. Walking into a meeting and sitting on one end of a long boardroom table is typically less inviting than sitting at a round table or sofa.

Think about the places you claim as your own – your home, an office, your car. Do they reflect who you are? Does your space invite people in or make them feel unwelcome?

Activity: Check Your Understanding

Key Takeaways

- Self-concept involves multiple dimensions and is expressed in internal monologue and social comparisons.

- Self-esteem refers to how you perceive your value and worth.

- Through self-disclosure, we disclose personal information and learn about others.

- The social penetration theory argues that self-disclosure increases in breadth and depth as a relationship progresses, like peeling back the layers of an onion.

- We engage in social comparison through self-disclosure, which may determine whether or not we pursue a relationship.

Exercises

- Define yourself in 20 words or less. Was it a challenge? Did your description focus on your characteristics, beliefs, actions, or other factors associated with you? If you compare your results with others, what did you observe?

- Identify at least three of your firmly held beliefs. What is the foundation of those beliefs? Consider how your beliefs may differ from your clients and how this can influence your communication and therapeutic relationships.

- Have you experienced negative results due to self-disclosure (as sender or receiver)? If so, what could have been altered in what, where, when, or how to disclose that may have improved the situation?

- Under what circumstances is it okay to share information that someone has disclosed to you? Under what circumstances is not okay to share the information?

- How does self-disclosure facilitate the therapeutic relationship in a professional healthcare environment?

References

Adamson, A., & Jenson, V. (Directors). (2001). Shrek [Film]. DreamWorks Animation; PDI/Dreamworks.

Adler, R. B., & Proctor, R. F. (2017). Looking out, looking in (15th ed.). Cengage.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W.H. Freeman.

Beebe, S. A., Beebe, S. J., & Ivy, D. K. (2010). Communication principles for a lifetime (4th ed.). Allyn & Bacon.

Best, D. L., & Thomas, J. J. (2004). Cultural diversity and cross-cultural perspectives. In A. H. Eagly, A. E. Beall, & R. J. Sternberg (Eds.), The psychology of gender (2nd ed., pp. 296–327). Guilford Press.

Bowles, D. D. (1993). Biracial identity: Children born to African-American and White couples. Clinical Social Work Journal, 21(4), 418–422. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00755575

Cooley, C. (1922). Human nature and the social order. Scribner.

DeHart, T., & Pelham, B. W. (2007). Fluctuations in state implicit self-esteem in response to daily negative events. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 43(1), 157–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2006.01.002

Derlega, V. J., Metts, S., Petronio, S., & Margulis, S. T. (1993). Self-disclosure. SAGE.

Fiske, S. T., & Taylor, S. E. (1991). Social cognition (2nd ed.). McGraw Hill.

Greene, K., Derlega, V. J., & Mathews, A. (2006). Self-disclosure in personal relationships. In A. L. Vangelisti & D. Perlman (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of personal relationships. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511606632.023

Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. Doubleday.

Hargie, O. (2011). Skilled interpersonal interaction: Research, theory, and practice. Routledge.

Higgins, E. T. (1987). Self-discrepancy: A theory relating self and affect. Psychological Review, 94(3), 319–340. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0033-295X.94.3.319

Human, L., Biesanz, J., Parisotto, K., & Dunn, E. (2012). Your best self helps reveal your true self: Positive self-presentation leads to more accurate personality impressions. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 3(1), 23–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550611407689

Jiang, L. C., Bazarova, N. N., & Hancock, J. T. (2011). The disclosure-intimacy link in computer-mediated communication: An attributional extension of the hyperpersonal model. Human Communication Research, 37(1), 58–77. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2010.01393.x

Jourard, S. (1964). The transparent self. Van Nostrand Reinhold.

Loughnan, S., Kuppens, P., Allik, J., Balazs, K., de Lemus, S., Dumont, K., Gargurevich, R., Hidegkuti, I., Leidner, B., Matos, L., Park, J., Realo, A., Shi, J., Sojo, V. E., Tong, Y.-Y., Vaes, J., Verduyn, P., Yeung, V., & Haslam, N. (2011). Economic inequality is linked to biased self-perception. Psychological Science, 22(10), 1254–1258. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797611417003

Morgan, W., & Wilson, S. R. (2007). Explaining child abuse as a lack of safe ground. In B. H. Spitzberg & W. R. Cupach (Eds.), The dark side of interpersonal communication. Lawrence Erlbaum.

Patzer, G. L. (2008). Looks: Why they matter more than you ever imagined. AMACOM.

Sosik, J. J., Avolio, B. J., & Jung, D. I. (2002). Beneath the mask: Examining the relationship of self-presentation attributes and impression management to charismatic leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 13(3), 217–242. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1016/S1048-9843(02)00102-9

Stefanone, M. A., & Lackaff, D. (2009). Reality television as a model for online behavior: Blogging, photo, and video sharing. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 14(4), 964–987. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2009.01477.x

Webber, L., & Korn, M. (2012, May 7). Yahoo’s CEO among many notable resume flaps. The Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/BL-DGB-24375

Wierzbicka, A. (2004). The English expressions good boy and good girl and cultural models of child rearing. Culture and Psychology, 10(3), 251–278.https://doi.org/10.1177/1354067X04042888

Wood, S. E., Green Wood, E., & Boyd, D. (2008). Mastering the world of psychology (3rd ed.). Allyn & Bacon.

Attribution Statement

Content adapted, with editorial changes, from:

Anonymous. (2019). Self-disclosure & interpersonal communication. Libre Texts. https://socialsci.libretexts.org/?title=Under_Construction/Purgatory/Book:_Interpersonal_Communications/6:_Interpersonal_Communication_Processes/06.4:_Self-Disclosure_%26_Interpersonal_Communication. Used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence.

Chute, A., Johnson, S., & Pawliuk, B. (2023). Professional communication skills for health studies. MacEwan Open Books. https://doi.org/10.31542/b.gm.3. Used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence.

Fisher, T. A. (2021). Fundamentals of interpersonal communication. City University of New York. https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1044&context=bx_oers. Used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence.

University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. (2013). Communication in the real world [Adapted]. https://open.lib.umn.edu/communication/. Used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence.