1.10 Culturally responsive practice

1.10.1 Cultural responsiveness

The Professional Standards for Speech Pathologists in Australia (SPA, 2020) “define approaches to professional practice that acknowledge past and current wrongs. They highlight the need to listen to, respect, learn from and collaborate with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples to achieve equitable health, well-being, language and educational outcomes for individuals, families and communities” (SPA, 2020, p. 3). In 2023, the SPA Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culturally responsive capability framework was published.

In this video, SPA Reconciliation Action Plan officer, Pauline Weldon-Bowen, discusses the importance of the journey to reconciliation.

National Reconciliation Week – Pauline Weldon-Brown by Speech Pathology Australia

Cultural responsiveness ‘describes the capacity to respond to the healthcare issues of diverse communities’ (Victorian Department of Health, 2009, pg. 4). The term cultural responsiveness is not specific to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, rather, the term applies to the responsiveness of health professionals to individuals’ and communities’ health beliefs and practices, and cultural and linguistic diversity. Cultural responsiveness is advocated by Indigenous Allied Health Australia (IAHA) through its Cultural Responsiveness in Action Framework (IAHA, 2019). As outlined by IAHA (2019, p. 5), “cultural responsiveness is what is needed to transform systems; how individual health practitioners work to deliver and maintain culturally safe and effective care”.

Culturally responsive healthcare practice is a strengths-based and action-oriented approach that focuses on the provision of person-centred services that acknowledge and respects cultural difference, and the social and cultural factors that may impact a person’s health (Gill & Babacan, 2012; Hyter & Salas-Provance, 2019; IAHA, 2019).

The operationalisation and actions of culturally responsive practice must occur at the individual and institutional level so patients feel culturally safe when accessing and participating in healthcare services (Gill & Babacan, 2012). In the Australian context, cultural responsiveness is a priority tenet in professional SLP practice documents including the code of ethics (Speech Pathology Australia, 2020a), and professional standards (Speech Pathology Australia, 2020b). Additionally, the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culturally responsive capability framework (SPA, 2023) provides guidance and support for SLPs and organisations in ways to facilitate culturally responsive practice. Cultural responsivity is a lifelong professional development practice and generally draws on concepts including cultural awareness (Coffin, 2007).

To be genuinely culturally responsive, you need to develop skills, knowledge, capabilities and competencies in relation to cultural awareness so that your services are culturally safe and secure as determined by the users of your services. There are numerous terms (e.g. cultural safety, cultural awareness, cultural security, cultural competence, cultural awareness, cultural capabilities) that are associated with and are the foundations for ‘cultural responsiveness’. An outline of some of these terms are provided below. You will find that these terms may be used interchangeably in various contexts but there are key distinctions between the terms.

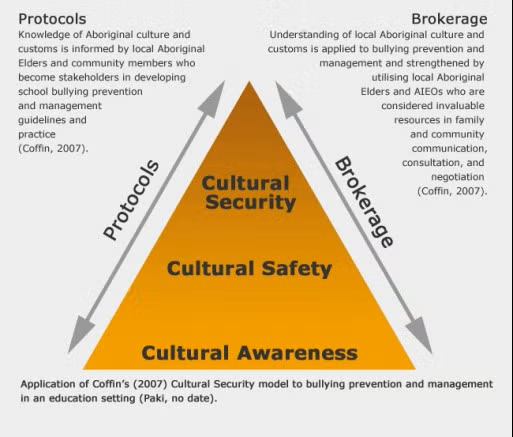

A useful cultural security model has been outlined by Juli Coffin (2007). In this model (Figure 7), Juli highlights the concepts of cultural awareness, cultural safety, and cultural security, and aligns the model with speech pathology practice examples. In the model, you can see the interconnectedness between these concepts, however there are key differences between these terms.

1.10.2 Cultural awareness

One of the first steps to practicing cultural responsiveness, and ultimately achieving cultural safety as determined by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples receiving the health service, is cultural awareness (Coffin, 2007; Taylor & Guerin, 2014). Cultural awareness involves demonstrating an awareness of, and sensitivities to, difference and diversity, and therefore, different care is required for different peoples (Taylor & Guerin, 2014). Cultural awareness also involves awareness of one’s own culture and influences upon behaviours, judgements and beliefs (Taylor & Guerin, 2014). However, cultural awareness does not necessarily lead to action. It is only when action is implemented as an outcome of cultural awareness, that cultural responsiveness, and facilitation of cultural safety, occur (Coffin, 2007).

Cultural awareness example

1.10.3 Cultural safety

Cultural safety has its foundations in Aotearoa New Zealand in the area of nursing and midwifery (Papps & Ramsden 1996). Cultural safety is the experience of the recipient of care, it is not defined by the caregiver or health provider (Mohamed et al., 2024). ‘cultural safety is not something that the practitioner, system, organisation or program can claim to provide, but rather it is something that is experienced by the consumer/client’ (Walker et al., 2014, p.201).

Working toward cultural safety is a lifelong journey and the key focus areas of cultural safety include analysis of power racism, ongoing effects of colonisation and white privilege (Mohamed et al., 2024). Cultural safety will only be experienced if the system is changed, adapted and/or challenged to incorporate respect for ‘Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ways of knowing, being and doing’ (IAHA, 2019). Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander people will determine if their cultural identity and meanings are being respected, they are not being subjected to racism, and they feel valued, safe, and trusted.

Cultural safety example

1.10.4 Cultural security

The term cultural security is more likely to be used in the Northern Territory and Western Australia. Cultural security shifts the focus from individual practitioners or staff to the health and human services systems in which they operate, and the decisions and actions of government and non-Indigenous parties. It relates to how systems ensure that the rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples to access and receive high quality services are met through the consideration and incorporation of culture in policy and practice (Australian Human Rights Commission 2011; Coffin 2007; Mohamed et al., 2024). Cultural security directly links understandings and actions, and government/workplace policies create processes that are automatically applied (Coffin, 2007).

Cultural security example

Activity

Access the SPA Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culturally responsive capability framework and complete the following quiz:

Review the ‘capabilities in action’ and ‘outcomes’ for each of the five culturally responsive capabilities. How might you enact these on an individual or personal level?

‘describes the capacity to respond to the healthcare issues of diverse communities’ (Victorian Department of Health, 2009, pg. 4).

Cultural awareness involves demonstrating an awareness of, and sensitivities to, difference and diversity, and therefore, different care is required for different peoples (Taylor & Guerin, 2014). Cultural awareness also involves awareness of one’s own culture and influences upon behaviours, judgements and beliefs (Taylor & Guerin, 2014).

Cultural safety is the experience of the recipient of care, it is not defined by the caregiver or health provider (Mohamed et al., 2024). ‘cultural safety is not something that the practitioner, system, organisation or program can claim to provide, but rather it is something that is experienced by the consumer/client’ (Walker et al., 2014, p.201).

Cultural security shifts the focus from individual practitioners or staff to the health and human services systems in which they operate, and the decisions and actions of government and non-Indigenous parties. It relates to how systems ensure that the rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples to access and receive high quality services are met through the consideration and incorporation of culture in policy and practice (Australian Human Rights Commission 2011; Coffin 2007; Mohamed et al., 2024).