2.4 Morphology

In this section, we look at words and at the meaningful pieces that combine to create words. We will see that languages vary in how words are built, but that nonetheless we can find structure inside of words in all languages. In linguistics, the study of word forms is known as morphology. A morpheme is the smallest meaning unit in a language.

2.4.1 What is morphology?

In linguistics, morphology is the study of how words are put together. For example, the word cats is put together from two pieces: cat, which refers to a particular type of furry four-legged animal (), and -s, which indicates that there’s more than one such animal (

). Most words in English have only one or two pieces in them, but some technical words can have many more, like non-renewability, which has at least five (non-, re-, new, -abil, and -ity). In many languages, though, words are often made up of many parts, and a single word can express a meaning that would require a whole sentence in English. Not all combinations of pieces are possible, however. To go back to the simple example of cat and -s, in English we can’t put those two pieces in the opposite order and still get the same meeting—scat is a word in English, but it doesn’t mean “more than one cat”, and it doesn’t have the pieces cat and -s in it, instead it’s an entirely different word.

What is a word?

If morphology is the investigation of how words are put together, we first need a working definition of what a word is.

In everyday life, in English we might think of a word as something that’s written with spaces on either side. This is an orthographic (or spelling-based) definition of what a word is. But just as writing isn’t necessarily a reliable guide to a language’s phonetics or phonology, it doesn’t always identify words in the sense that is relevant for linguistics. And not all languages are written with spaces in the way English is—not all languages have a standard written form at all. So we need a definition of “word” that doesn’t rely on writing.

The definition of “word” is actually a hotly debated topic in linguistics! Linguists might distinguish phonological words (words for the purposes of sound patterns), morphological words (words for the purposes of morphology), and syntactic words (words for the purposes of sentence structure), and might sometimes disagree about the boundaries between some of these.

For the purposes of linguistic investigation of grammar we can say that a word is the smallest separable unit in language.

What this means is that a word is the smallest unit that can stand on its own in an utterance. For example, content words in English (nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs) can stand by themselves as one-word answers to questions, as you can see in the mini-dialogues in (1).

| (1) | a. | What do you like to eat? |

| Answer: cake (noun) | ||

| b. | What did you do last night? | |

| Answer: sleep (verb) | ||

| c. | What colour is the sky today? | |

| Answer: orange (adjective) | ||

| d. | How did you wake up this morning? | |

| Answer: slowly (adverb) |

Words are also syntactically independent, which means they can appear in different positions in a sentence, changing their order with respect to other elements even while the order of elements inside each word stays the same. Even though words are the smallest separable units of language, that doesn’t mean that words are the smallest unit of language overall. As we already saw earlier in this section, words themselves can have smaller pieces inside them, as in the simple cases of cats (cat–s) or non-renewability (non-re-new-abil-ity)—but these smaller pieces can’t stand on their own.

To refer to these smaller pieces within words, we use the technical term morpheme. A morpheme is the smallest systematic pairing of both form (sign or sound) and meaning or grammatical function. (We say “meaning or grammatical function” instead of just “meaning” because while some morphemes have clear meanings in the context of lexical semantics, other morphemes express more abstract grammatical information.) In other words, a morpheme is the smallest meaning unit in a language. Words that contain more than one morpheme, like cats or nonrenewability, are morphologically complex. Words with only a single morpheme, like cat or new, are morphologically simple.

Our goal in morphology is to understand how words can be built out of morphemes in a given language. We will explore the shapes of different morphemes (and morphological processes); in later sections we will review different functions that morphology can have, looking at divisions between derivational morphology, inflectional morphology, and compounding.

2.4.2 Roots, bases and affixes

Affixes vs roots

Morphemes can be of different types, and can come in different shapes. Some morphemes are affixes: they can’t stand on their own, and have to attach to something. The morphemes -s (in cats) and inter– and -al (in international) are all affixes.

The thing an affix attaches to is called a base. Just like whole words, some bases are morphologically simple, while others are morphologically complex.

For example, consider the word librarian. This word is formed by attaching the affix -ian to the base library. Librarian can then itself be the base for another affix: for example, the word librarianship, the state or role of being a librarian, is formed by attaching the affix -ship to the base librarian. There is a special name for simple bases: root. A root is the smallest possible base, which cannot be divided, what we might think of as the core of a word.

Turning back to affixes, an affix is any morpheme that needs to attach to a base. We use the term “affix” when we want to refer to all of these together, but we often specify what type of affix we’re talking about.

A prefix is an affix that attaches before its base, like inter- in international.

A suffix is an affix that follows its base, like -s in cats.

A circumfix is an affix that attaches around its base.

An infix is an affix that attaches inside its base.

A simultaneous affix is an affix that takes place at the same time as its base.

Prefixes and suffixes are very common, not only in English but also in other languages. Circumfixes, infixes, and simultaneous affixes are less common, and we will not focus on these in this book.

Free and bound morphemes

Another way to divide morphemes is by whether they are free or bound. A free morpheme is one that can occur as a word on its own. For example, cat is a free morpheme. A bound morpheme, by contrast, can only occur in words if it’s accompanied by one or more other morphemes. For example, the ‘ing‘ on the end of the word ‘reading‘ is a bound morpheme. It cannot exist on it’s own in the English language – it needs to be attached to another morpheme (in this case a free morpheme) to have meaning.

Because affixes by definition need to attach to a base, only roots can be free. In English most roots are free, but we do have a few bound morpheme roots that can’t occur on their own. For example, the root -whelmed, which occurs in overwhelmed and underwhelmed, can’t occur on its own as *whelmed.

In many other languages, though, all (or most) roots are bound, because they always have to occur with at least some morphology. This is the case for verbs in French and the other Romance languages, for example; it was also the case for Latin, which is why the roots nat- and libr- were shown with hyphens above.

We show that morphemes are bound by putting hyphens either before or after them, on the side that they attach to other morphemes. This applies to bound roots as well as to affixes.

Morphology beyond affixes

There are some morphological patterns that don’t obviously involve affixes at all. In this section we discuss a few examples: internal change, suppletion, and reduplication.

Internal change

Internal change is one name for the type of change found in many irregular English noun plurals and verb past tenses.

For example, for many speakers of English the plural of mouse is mice, the plural of goose is geese, the past tense of sit is sat, and the past tense of write is wrote

These are all relics of what used to be a regular pattern in English. By regular we mean that they were phonologically predictable based on the general pattern of the language, and automatically applied to new words. For speakers of English today, changes like “mouse becomes mice when it’s plural” have to be memorized, and are therefore irregular.

Suppletion

Suppletion is an even more irregular pattern, where a particular morphological form involves entirely replacing the form of a morpheme. Suppletion is always irregular—you can never predict what the result of suppletion will be, it always has to be memorized. For example, the past tense of the verb go is went—there is no amount of affixation or internal change that will get you from one to the other. This type of total replacement is also found in English in the comparatives and superlatives good ~ better ~ best and bad ~ worse ~ worst, throughout the paradigm of the verb to be, and on some pronouns.

If a language has suppletion (and not all languages do!) it is commonly found on some of the most frequent words in the language, just as we see in English. The reason for this is that children acquiring a language tend to assume patterns are regular and predictable until the weight of the evidence convinces them otherwise—and they’re more likely to get enough evidence to reach the conclusion that something is suppletive if a word is incredibly common. Suppletion is a type of allomorphy, which we will learn more about in a section below.

Reduplication

Finally, reduplication involves repeating part or all of a word as part of a morphological pattern. English does have one pattern of reduplication, which can apply to phrases as well as words. This type of reduplication carries the meaning of something being a prototypical example of the type; it is often called salad-salad reduplication by linguists. For example, in my variety of English I can say: “Tuna salad is a salad, but it’s not a salad-salad.”—in other words, tuna salad isn’t a prototypical salad because it doesn’t involve lettuce or other leafy green vegetables.

2.4.3 Allomorphy

Some morphemes have a consistent meaning, but appear in different forms depending on the environment where they occur. When a morpheme can be realized in more than one way, we refer to its different forms as allomorphs of the morpheme. In other words, allomorphy. In English, for example, the indefinite article shows up as a when it occurs before a consonant (a book), but as an when it occurs before a vowel (an apple). This is an example of allomorphy based on the phonology (sounds) that appear before or after the morpheme (the phonological environment). This is called phonologically conditioned allomorphy.

Another example of allomorphy can be found in the plural forms of English nouns. First, consider the pairs of singular and plural nouns in (1).

| (1) | singular | plural | ||

| a. | [s] | book | books | |

| cat | cats | |||

| nap | naps | |||

| b. | [z] | paper | papers | |

| dog | dogs | |||

| mile | miles | |||

| c. | [ɪz] or [əz] | niece | niece | |

| horse | horses | |||

| eyelash | eyelashes |

The plural in all these words is spelled as “s” (or “es”), but it isn’t always pronounced the same way. If you pay attention, the plural adds the sound [s] in (1a), the sound [z] in (1b), and the sound [ɪz] or [əz] in (1c). Just like the alternation between a and an, this is predictable phonologically conditioned allomorphy, based on the last sound in the noun root.

Now look at the singular-plural pairs in (2). These examples show more allomorphs of the plural in English, but they are not predictable: the allomorph of the plural used with these roots has to be remembered as a list.

| (2) | singular | plural | ||

| a. | -(r)en | child | children | |

| ox | oxen | |||

| b. | internal change | mouse | mice | |

| goose | geese | |||

| woman | women | |||

| c. | no change (-∅) | fish | fish | |

| sheep | sheep | |||

| deer | deer |

Allomorphy that is determined by the root, like in (2), is called lexically conditioned allomorphy.

2.4.4 Lexical categories

Derivation vs inflection and lexical categories

Morphology is often divided into two types:

- Derivational morphology: Morphology that changes the meaning or category of its base

- Inflectional morphology: Morphology that expresses grammatical information appropriate to a word’s category

We can also distinguish compounds, which are words that contain multiple roots into a single word.

The definitions of derivation and inflection above both refer to to the category of the base to which morphology applies. What do we mean by “category”? The category of a word is often referred to in traditional grammar as its part of speech. In the context of morphology we are often interested in the lexical categories, which is to say nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs. The rest of this section gives an overview of what lexical categories are, and how we can identify them.

Lexical Categories (word classes), aka “Parts of Speech”

Determining the category of a word (or word class) is an important part of morphological and syntactic analysis. A category of words or morphemes is a group that behave the same way as one another, for grammatical purposes.

You might be familiar with traditional semantic definitions for the parts of speech—definitions that are based on a word’s meaning. If you ever learned that a noun is a “person, place or thing”, or that a verb is an “action word”, these are semantic tests. However, semantic tests don’t always identify the categories that are relevant for linguistic analysis. They can also be hard to apply in borderline cases, and sometimes yield inconsistent results; for example, surely action and event are “action” words, so according to the semantic definition we might think they’re verbs, but in fact these are both nouns!

We can define categories based on the grammatical contexts in which words or morphemes are used—their distribution. The distribution of different categories varies from language to language. We will explore below some of the main distributional tests for lexical categories (nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs) in English. Many of these tests involve syntactic distribution—how each lexical category combines with other words in phrases and sentences.

Nouns (N)

Syntactic tests for nouns in English:

- Can follow a determiner, as in: an event or the proposal

- Can be modified by adjectives, as in: a happy event or the new proposal

- Can be the subject or object of a verb, as in: Events occurred. or We made proposals.

- Can be replaced by a pronoun, as in: Events occurred. → They occurred.

- Do not allow objects (without a preposition).

Morphological tests for nouns in English:

- Have singular and plural forms: e.g. books, governments, happinesses

Note: The plurals of some abstract nouns can seem odd! Think outside the box to find contexts where they might naturally occur.

Verbs (V)

Syntactic tests for verbs in English:

- Can combine with auxiliary verbs, as in: can remain, will know, have thought, be kicking.

- Can follow the infinitive marker to, as in: to kick, to think, to remain, to know.

- Can take an object (without a preposition), as in: kick the ball.

Morphological tests for verbs in English:

-

- Have a third person singular present tense form with -s, as in: (she/he/it) kicks, goes, remains.

- Have a regular past tense form, usually (but not always) with -ed, as in: (she/he/it) kicked, went, remained.

- Have a perfect/passive form, usually with -ed or -en, as in: (she/he/it) has kicked, gone, remained.

- Have a present progressive form with -ing, as in: kicking, going, remaining.

Adjectives (Adj)

Syntactic tests for adjectives in English:

- Modify nouns (occur between a determiner and a noun), as in: a happy event or the new proposal.

- Can be modified by very (but so can many adverbs!), as in: very happy, very new.

- Do not allow noun phrase objects. If objects are possible, they must be introduced in a prepositional phrase. There are a handful of exceptions to the generalization that adjectives only take prepositional phrase objects, depending on your variety of English.

Morphological tests for adjectives in English:

- Can often be suffixed by -ish

- May have comparative and superlative forms (e.g. happier, happiest)

Adverbs (Adv)

Syntactic tests for adverbs in English:

- Modify verbs, adjectives, and other adverbs (anything but nouns!).

- Cannot appear alone between a determiner and a noun.

- Can be modified by very (but so can adjectives!).

Morphological tests for adverbs in English:

- Many ( but not all) adverbs end in -ly

Using derivational affixes to identify category

In addition to the morphological tests above, you can also use derivational affixes to help determine the category of a word. For example:

- Suffixes like -ment and -ness always create nouns; the base that -ment attaches to is always a verb (if it’s a free form), and the base of -ness is usually an adjective.

- Suffixes like -ify and -ize always create verbs; their bases are nouns (if they’re free forms).

The property of derivational affixes to not only create particular categories, but also to attach to specific categories, is called selection.

2.4.5 Derivational morphology and selection

Derivational morphemes are typically choosy about the types of bases they combine with—another word for “choosy” is selective, and so we talk about how derivational affixes select the category of their base. For example, the suffix -able combines only with verbs, and always creates adjectives meaning “able to be verb-ed”: readable, writeable, playable, employable, and googleable are all possible adjectives in English, even if they don’t appear in a dictionary—while the other words in this list probably do show up in most dictionaries, googleable might not, because google a relatively recent verb (adapted from the name of the company).

The list in (1) is a very incomplete sample of derivational suffixes in English, with the category they select on the left side of the arrow, and the category they create on the right side.

| (1) | -tion | V | → | N | |

| -able | V | → | Adj | ||

| -en | V | → | Adj | ||

| -ed | V | → | Adj | ||

| -ing | V | → | Adj or N | ||

| -ment | V | → | N | ||

| -ness | Adj | → | N | ||

| -ity | Adj | → | N | ||

| -ous | N | → | Adj | ||

| -hood | N | → | N | ||

| -ize | N | → | V | ||

| -ly | Adj | → | Adj | ||

| -ish | Adj | → | Adj |

There are many more than this! You’ll see them inside many words if you start paying attention.

Prefixes in English never change the category of the base they attach to, but they express clear meanings, like negation, repetition, order (e.g. pre- and post-), etc. Examples of English derivational prefixes and the categories they select appear in (2):

| (2) | non- | N | → | N | non-issue | |

| Adj | → | Adj | non-distinct | |||

| un- | V | → | V | undo | ||

| Adj | → | Adj | unhappy | |||

| re- | V | → | V | redo |

Derivational morphology can be even more selective, requiring not only a base that belongs to a certain category, but requiring specific roots or bases. A lot of derivational morphology in English was acquired from borrowing words from French and Latin; these “latinate” affixes often prefer to combine with each other, and sometimes only with roots that are also latinate. Such affixes are less productive than other affixes, which combine freely with most bases.

Some of the most productive derivational suffixes in English are -ish, which can attach to most adjectives, -ness, -able, and -ing.

-ing is particularly productive: it can attach to all verbs in English to form adjectives (traditionally called “participles”) or nouns (traditionally called “gerunds”). It is very unusual for a derivational affix to be that productive; usually there are at least a few roots that don’t occur with a derivational affix, for whatever reason.

2.4.6 Inflectional morphology

Unlike derivational morphology, inflectional morphology never changes the category of its base. Instead it simply suits the category of its base, expressing grammatical information that’s required in a particular language.

In English we find a very limited system of inflectional morphology:

- Nouns

- Number: singular vs. plural

- Case (only on pronouns)

- Nominative: I, we, you, he, she, it, they

- Accusative: me, us, you, him, her, it, them

- Possessive: my, our, your, his, her, its, their

- Verbs

- Agreement: most verbs agree with third person singular subjects only in the present tense (-s), but the verb to be has more forms.

- Tense: Past vs. Present

- Perfect/Passive Participle: -ed or -en (Perfect after auxiliary have, Passive after auxiliary be)

- Progressive -ing (after auxiliary be)

- Adjectives

- Comparative -er, Superlative -est (Arguable! Some people might treat this as derivational)

One thing about inflectional morphology is that lots of it can be expressed syntactically instead of morphologically. So some languages have tense, but express it with a particle (a separate word) rather than with an affix on the verb. This is still tense, but it’s not part of inflectional morphology.

Types of inflectional distinctions

There are many types of inflectional distinctions commonly made in the world’s languages, but we will focus on the following common types related to English: Number, Person, Case, Agreement, Tense and Aspect, and Negation.

Number

Most languages, if they have grammatical number, just distinguish singular (“one”) vs. plural (“more than one”), but number systems can be more complex as well. For example, many languages have dual in addition to singular and plural. Dual number is used for groups of exactly two things; we have a tiny bit of dual in English with determiners like both, which means “strictly two”. You have to replace both with all if a group has three or more things in it. But in English we don’t have any morphological marking of dual.

Person

Person distinctions are those between first person (I, we), second person (you), and third person (he, she, it, they). Some languages make a further distinction in the first person plural between a first person inclusive (me + you, and maybe some other people) and a first person exclusive (me + one or more other people, not you).

Case

Case refers to marking on nouns that reflects their grammatical role in the sentence. Most case systems have ways to distinguish the subject from the object of a sentence, as well as special marking for possessors and indirect objects. In modern English, case is only marked on pronouns. The case found on subject pronouns is called nominative, the case found on object pronouns (and in most other positions) is called accusative, and the case found on possessors is called genitive (or sometimes just “possessive”). It is also common to have a case found primarily on indirect objects, which is called dative. There is no morphological dative case in English.

Agreement

Agreement refers to any inflectional morphology that reflects the properties of a different word in a sentence, usually a noun. The most common type of agreement is verbs agreeing with their subject, though verbs in some languages might also agree with their object (or might sometimes agree with their object instead of their subject). Verbs usually agree with nouns for their number and person, but they can agree for other properties as well. Determiners, numerals, and adjectives often agree with the noun they modify, usually for some combination of number, case, and gender—assuming a language has some or all of these types of inflection in the first place!

Tense and Aspect

Tense refers to the contrast between present and past (or sometimes between future and non-future) and is typically marked on verbs. Aspect is a bit harder to define, but is usually characterized as the perspective we take on an event: do we describe it as complete, or as ongoing? In English we have progressive (marked with be + –ing) and perfect aspect (have + –ed/-en).

Negation

In English we have derivational negative morphology (as in the prefixes in- or non-), which negates the meaning of a base or root. Inflectional negation, by contrast, makes a whole sentence negative. In English we express inflectional negation syntactically, with either the word not (or its contracted clitic form –n’t). In other languages, however, negation can be expressed by inflectional affixes.

2.4.7 Compounding: Putting roots together

The last main “type” of morphology is compounding. Compounds are words built from more than one root (though they can also be built from derived words): if you find a word that contains more than one root in it, you are definitely dealing with a compound. Compounding differs from both derivation and inflection in that it doesn’t involve combinations of roots and affixes, but instead roots with roots.

English is a language that builds compounds very freely. For almost any two categories, you can find examples of compounds in English.

Noun-Noun compounds include:

- doghouse

- website

- basketball

- sunflower

- moonlight

- beekeeper

- heartburn

- spaceship

Adjective-Noun compounds include:

- greenhouse

- bluebird

Verb-Noun compounds include:

- breakwater

- baby-sit

Noun-Adjective compounds include:

- trustworthy

- watertight

Adjective-Adjective compounds include:

- purebred

- kind-hearted

- blue-green

Noun-Verb compounds include:

- browbeat

- manhandle

- sidestep

Adjective-Verb compounds include:

- blacklist

2.4.8 How to draw morphological trees

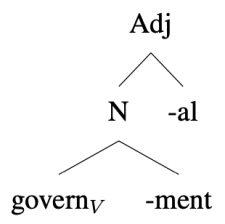

In previous sections we saw that the order in which we attach derivational affixes, or the order in which we build compound words, sometimes matters. So a word like “governmental”, isn’t just a string of the root govern + the suffix –ment + the suffix –al. Instead, it’s the result of first combining govern and –ment, and then combining the result of that with a further suffix –al.

We often represent this type of structure with a tree diagram. Trees are used to represent the constituency of language, the subgroupings of pieces within a larger word or phrase. One of the big insights of linguistics is that constituency is always relevant when describing how pieces combine together, whether we’re looking at morphemes within a word or words within a sentence. (though different theories in linguistics often take different views of what range of hierarchical structures are possible in natural languages.) The morphological tree diagram for the word government is provided in Figure 22.

When drawing a morphological tree, we can follow these steps:

- Identify the root and any affixes

- 1 root: non-compound word

- 2 roots: compound word

- Determine the category of the root

- Determine the order in which affixes attach

- Determine the category of any intervening bases, and of the whole word.

You might find that it makes sense to do these in different orders, or in different orders in different words. The best way to find out what works for you is to practice.

2.4.9 Functional categories

We learned above about some words having lexical categories. These were nouns, verbs, adjectives and adverbs. As we will next be discussing syntax (phrases and sentences), not all words in a sentence belong to these four categories.

Consider the sentence in (1).

| (1) | The spaceship will arrive in orbit very soon. |

Spaceship is a noun, and it is the head of the noun phrase [the spaceship] (we can tell because it could be replaced by a pronoun like it). But what category is the? Similarly, arrive is a verb, orbit is a noun, and soon is an adverb, but what categories do will, in, and very belong to?

Words like the, will, in, and very belong to functional categories. Functional categories can be thought of as the grammatical glue that holds syntax together. While lexical categories mostly describe non-linguistic things, states, or events, functional categories often have purely grammatical meanings or uses. Some of the most important functional categories that we’ll use in this book are described in this section.

Determiner

You may be familiar with the definite article the and indefinite article a(n), as in the book or a cat.

| (2) | a. | the book |

| b. | a cat |

In English, definite and indefinite articles occur in noun phrases before the head noun, as well as before any numbers or adjectives, as we see in the examples in (3):

| (3) | a. | the three red books |

| b. | a large angry cat |

In fact, articles are usually the very first thing in a noun phrase, and you can only have one of them (unlike adjectives, which you can pile up). If you try to have more than one, the result is ungrammatical, as we can see in (4)—for me it’s not grammatical to say *a the book or *the a cat.

| (4) | a. | *a the book |

| b. | *the a cat |

This distribution doesn’t apply only to the articles the and a(n), though. There are a bunch of other elements that occur in exactly the same places, with exactly the same restrictions. These other things aren’t articles in traditional grammar, so we use the label determiners for this larger functional category (usually abbreviated Det).

Some other determiners:

- Demonstratives (this, that, these, those)

- Some quantifiers (every, some, each, most, etc.)

Test for yourself that these occur in the same places in noun phrases as the and a(n) do—and that some other words expressing quantities (like all and many) and numbers do not.

Possessors in English expressed by possessive pronouns or by noun phrases marked with ‘s also appear in the same position as determiners, and are also in complementary distribution with them, as shown in (5).

| (5) | a. | my book |

| b. | [a friend from school]’s cat | |

| c. | *the [a friend from school]’s cat | |

| d. | *[a friend from school]’s the book |

Notice that the marker ‘s attaches to the whole phrase, rather than to the head noun friend; this makes it a clitic rather than an affix, and makes it different from possessor marking typically found in languages that have genitive case.

Possession in English can also be marked with a prepositional phrase, which would come after the noun and not be in complementary distribution with determiners: the cat [of my friend from school].

Not all languages have definite and indefinite articles, but most languages have some kind of determiners.

Pronouns

Pronouns are a special functional category that can replace a whole noun phrase. The set of pronouns in the variety of English most Australians speak is limited to the following, where each row lists the nominative, accusative, and possessive forms of the pronoun:

- First person singular: I / me / my

- First person plural: we / us / our

- Second person singular or plural: you / you / your

- Third person singular inanimate: it / it / its

- Third person singular feminine: she / her / her

- Third person singular masculine: he / him / his

- Third person animate singular or general plural: they / them / their

Auxiliaries

Auxiliaries (abbreviated Aux) are like verbs in that they can be present or past tense, and can show agreement, but they always occur alongside a lexical main verb. For this reason they’re sometimes called “helping verbs”.

For example, in the progressive in English we see the auxiliary be, alongside a main verb that ends in the inflectional suffix -ing, as in (6):

| (6) | The bears are dancing. |

In English declarative sentences, auxiliaries occur after the subject and before the main verb.

If an English sentence is negative, at least one auxiliary will occur to the left of negative not /n’t, as you see in (7):

| (7) | The bears aren’t dancing. |

In a Yes-No questions in English, at least one auxiliary appears at the front of the sentence, before the subject, as you see in (8):

| (8) | Are the bears dancing? |

The auxiliaries in English are:

- have (followed by a past participle, in the perfect)

- be (followed by a past participle in the passive, and a present participle in the progressive)

- do (used in questions and negation when there’s no other auxiliary)

Importantly, these can all also be used as main lexical verbs! They’re auxiliaries only when there’s also another verb in the clause that’s acting as the lexical verb. If have expresses possession, or be is followed by a noun or adjective instead of a verb, they are occurring as main verbs.

In English there is also a class of modal auxiliaries. In modern English modals only occur as auxiliaries—they don’t have uses as main verbs—and they are different from the other auxiliaries in that they don’t agree with the subject. The modal auxiliaries are:

- will

- would

- can

- could

- may

- might

- shall (archaic for many people)

- should

- must

Prepositions

Prepositions (abbreviated P) express locations (temporal/spatial) or grammatical relations. They are almost always followed by noun phrases (though a few prepositions can occur by themselves)—in other words, they are almost always transitive and select a noun phrase complement. Prepositions can sometimes be modified by degree words like very or way. Those modifiers, the preposition, and the following noun phrase, all group together into a prepositional phrase constituent.

Some prepositions:

- on

- up

- beside

- through

- outside

- in

- above

- to

- of

- with

- for

- without

Chapter Attribution

This chapter has been adapted in parts from:

Essentials of Linguistics (2nd edition) by Anderson et al. (2022). Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

A morpheme is the smallest meaning unit in a language.

A free morpheme is one that can occur as a word on its own. For example, cat is a free morpheme.

A bound morpheme, by contrast, can only occur in words if it’s accompanied by one or more other morphemes. For example, the 'ing' on the end of the word 'reading' is a bound morpheme. It cannot exist on it's own in the English language - it needs to be attached to another morpheme (in this case a free morpheme) to have meaning.