2.5 Syntax

In this section we look at how words are organized into phrases and sentences, which in linguistics is called syntax.

2.5.1 Syntactic knowledge and grammaticality judgements

In linguistics, syntax is the study of how words are organized into phrases and sentences. Just as the morphemes in a word are organized into structures, the words in a sentence are also best viewed not just as a string of words, but instead as having a hierarchical structure. And just as words contain a head morpheme, we’ll see that every phrase has an element that is its syntactic head.

What kind of knowledge do we have about the syntax of a language we know? Let’s start by considering the sentence in (1):

| (1) | All grypnos are tichek. |

You might not know what a grypno is, or what it means to be tichek (because these are made-up words!), but you can tell that this sentence is still the right kind of “shape” for English. In other words, (1) is consistent with the way English speakers put words together into sentences.

Compare this with the sentence in (2):

| (2) | *Grypnos tichek all are. |

Unlike (1), (2) isn’t the right shape for a sentence in English. Even if you did know what a grypno was, or what it meant to be tichek, this still wouldn’t be the way to put those words together into a sentence in English.

Something we can be pretty confident about is that you’ve never heard or read either of these sentences before encountering them above. So that means that your internal grammar of English must be able to generalize to new cases—this is the generativity of language. As someone who uses language—in the case of (1) and (2), as someone who speaks and reads English—you can identify sentences that do or do not fit the patterns required by your internal grammar. In syntax we describe sentences that do match those patterns as grammatical for a given language user, and sentences that do not match required patterns as ungrammatical.

Grammaticality judgements in syntax

In syntax when we say something is ungrammatical we don’t mean that it’s “bad grammar” in the sense that it doesn’t follow the type of grammatical rules you might have learned in school or learned for your language. Instead, we call things ungrammatical when they are inconsistent with the grammatical system of language user.

The evaluation of a sentence by a language user is called a grammaticality judgement. Grammaticality judgements are a tool for investigating the linguistic system of an individual language user—there is no way to get a grammaticality judgement for “English” as a whole, only grammaticality judgements from individual English speakers. Despite that, sometimes you will see a sentence described as grammatical or ungrammatical “in English” or another language; technically this is a shorthand for saying that users of English (or another language) generally agree about whether it is grammatical or not. In many cases different users of a language disagree about the status of a particular example, and this tells us something about syntactic variation in that language!

2.5.2 Word order

If you think about hearing or seeing a sentence, or if you think about reading a sentence that’s been written down, a really obvious property is that words and morphemes come in a particular order. Indeed, the only difference between the grammatical and ungrammatical sentences we saw above, repeated below in (1), is that the words appear in different orders.

| (1) | a. | All grypnos are tichek. |

| b. | *Grypnos tichek all are. |

The English language has relatively fixed word order. Typically, English is Subject-Verb-Object (SVO) word order language. There isn’t much flexibility in English to change the order of words in a sentence, without either changing the meaning or making the sentence ungrammatical. Lots of other languages also have relatively fixed word order—among them French —but lots of other languages have much more flexible word order. Languages with relatively flexible word order include Latin, Russian, Greek, and AUSLAN, to name just a few. For users of these languages, the order of words in a sentence is often determined by style or by the topic or focus of the sentence.

What is the basic order of words in English sentences? A generalisation would be to say that the verb in an English sentence has to come after at least one noun, and that it can be followed by a second noun, but doesn’t have to be. We could write this generalization as a kind of formula or template: the grammatical sentences in (2) have the order N V (N) (the parentheses around the second “N” mean that it is optional).

Another way to describe word order involves talking not just about categories like nouns and verbs, but grammatical functions like subject and object. Word order in English doesn’t just require that any noun come before the verb, it has to be the noun that corresponds to the subject. Similarly, if the verb is a transitive verb with an object, the object noun must come after the verb. So even though Chocolate ate Amal. is a grammatical sentence of English (though with a somewhat implausible meaning), it can’t express the same meaning as Amal ate chocolate.

2.5.3 Key grammatical terminology

This section reviews some key grammatical terminology that you might be familiar with from elsewhere (for example, from language classes). This vocabulary is important for describing the basic structure of phrases and sentences, and we’ll use it frequently throughout this book.

Sentence

A sentence is a string of words that expresses a complete statement, question, or command. For statements (as opposed to questions or commands), a sentence expresses a proposition, something that can be true or false. A sentence is a clause that stands on its own as an utterance.

Clause

A clause is a constituent that includes a subject and a predicate. Some clauses occur inside other clauses (see complex sentence below), and so not all clauses are independent sentences.

Predicate

A predicate is the state, event, or activity that the sentence attributes to its subject. The word “predicate” is used in two ways. Sometimes it is used to refer to a single head or word (usually a verb or an adjective), but other times it is used to describe everything in the sentence other than the subject (for example, a whole verb phrase. In this chapter we use it in the first sense, to refer to a word that combines with a subject and (sometimes) one or more objects.

Arguments

Arguments are phrases that correspond to the participants or actors involved in a sentence’s predicate. They are typically noun phrases, but it’s possible to have arguments of other types (usually prepositional phrases or whole clauses).

In the sentences in (3) the arguments are in bold and the predicate is italicized.

| (3) | a. | Vanja loves chocolate. |

| b. | The children gave [the kitten] [a toy]. | |

| c. | Everyone is excited. |

CLASSIFYING PREDICATES

Predicates can be classified by their transitivity, which is the number of arguments they take. (This is also sometimes called the valency of a predicate.) The words for transitivity are based on the number of objects a predicate takes.

Intransitive

An intransitive predicate takes one argument (the subject); no object.Example 1: she laughed. The verb “laughed” is intransitive because it only requires a subject (“She”) and doesn’t need an object to complete the meaning.Example 2: the baby cried. The verb “cried” is intransitive because it only needs the subject “the baby” to form a complete thought.

Transitive

A transitive predicate takes two arguments (subject and direct object); one object.Example 1: she kicked the ball. The verb “kicked” is transitive because it takes both a subject (“She”) and a direct object (“the ball”). “The ball” is the entity that receives the action of the verb.Example 2: Mia ate the chocolate. The verb “ate” is transitive because it requires an object (“the sandwich”) in addition to the subject (“Mia”).

Ditransitive

A ditransitive predicate takes three arguments (subject, direct object, and indirect object); two objects.Example 1: she gave him a present. The verb “gave” is ditransitive because it requires a subject (“She”), a direct object (“a gift”), and an indirect object (“him”), the recipient of the gift.Example 2: I sent her a photo. The verb “sent” is ditransitive because it involves a subject (“I”), a direct object (“a photo”), and an indirect object (“her”), the recipient of the letter.

CLASSIFYING ARGUMENTS

Arguments can be classified in at least two ways: their position in the sentence, and how they’re related to the predicate (are they the actor, the thing acted upon, etc). For now we’ll focus on the position of arguments, with diagnostics specific to English.

Subject

Subjects almost always appear before the predicate in English, and control agreement on the verb. If the subject is a pronoun, it is in nominative case (I, we, you, he, she, it, they).

Direct object

Objects usually appear after the verb in English. If the direct object is a pronoun, it is in accusative case (me, us, you, him, her, it, them).

Indirect object

With ditransitive verbs, the indirect object is often the recipient of the direct object. The indirect object is often (but not always) marked by “to” or another preposition; in English, if the indirect object is a pronoun, it is in accusative case (but in languages that have dative case, indirect objects are often in dative case).

CLASSIFYING SENTENCES

Now that we’ve looked at grammatical terminology relating to predicates and arguments within sentences, let’s talk about terminology for sentences and clauses as a whole. First, we can classify them according to their function—whether they are used to make a statement, ask a question, or give a command.

Declarative

Declarative clauses are statements, things that can be true or false. For example: The sun sets in the west; The dog is barking.

Interrogative

Interrogative clauses are questions. Questions come in two general types:

- Yes-No questions, like: Did Romil watch a movie?

and - Content questions, like: What did Romil watch? Where did Romil watch the movie? Why did Romil watch the movie?

Imperative

Imperative clauses express requests or commands. For example: Open the door (please)!; Stop talking!; Close the door.

Alternatively, we can classify sentences according to their structure; that is, according to whether they contain one clause or more than one clause, and (if more than one clause) how the sub-clauses are related to one another.

Simple sentence

A sentence is simple if it contains only one clause. A clause requires a verb (and generally a subject). For example: She sings; I love pizza; The horse jumped the fence.

Compound sentence

A compound sentence has at least two clauses, linked by a conjunction like and, or, or but. For example: [ Mark laughed ] and [ Andy cried ]; [I wanted to go for a walk[, but [it started raining].

Complex sentence

A complex sentence is one that contains one independent clause and at least one independent (or subordinate) clause.Example 1: I went to the store because I needed some milk. The independent clause is “I went to the store,” and the dependent clause is “because I needed some milk,” introduced by the subordinating conjunction “because.”Example 2: Although it was raining, we decided to go for a hike. The independent clause is “we decided to go for a hike,” and the dependent clause is “Although it was raining,” introduced by “Although.”

2.5.4 Structure within the sentence: Phrases, heads and selection

Beyond the order of words, all human languages appear to group words together into constituents. The generalisations about which sentences people find grammatical and which ones they find ungrammatical don’t refer to purely linear properties like “fourth word in a sentence”, but instead to phrases in particular structural positions.

A phrase is a set of words that act together as a unit. Let’s look at the example in (1) to see what this means:

| (1) | All kittens are very cute. |

What other groups of words can appear in the same position as the words all kittens in this sentence?

| (2) | a. | Puppies are very cute. |

| b. | The ducklings that I saw earlier are very cute. | |

| c. | These videos of a baby panda sneezing are very cute. |

…and so on. It turns out that lots of different groups of words can go in this position—but not all of them! What all these examples have in common is that we’ve replaced [all kittens] with another group of words that includes at least one plural noun: puppies or ducklings or videos. If we swap in a singular noun, the sentences would be ungrammatical, as we see in (3).

| (3) | a. | *The puppy are very cute. |

| b. | *The duckling that I saw earlier are very cute. | |

| c. | *This video of a baby panda sneezing are very cute. |

…but if we change the plural verb are to the singular is they become good again (this is subject agreement inflection):

| (4) | a. | The puppy is very cute. |

| b. | The duckling that I saw earlier is very cute. | |

| c. | This video of a baby panda sneezing is very cute. |

It turns out that the groups of words that we can easily substitute here are all ones that have a noun in them. But it’s not enough to just have some noun in the group of words at the front of the sentence, as the examples in (5) show. (5a) is ungrammatical even though the string of words at the beginning includes the pronoun I—and this sentence is ungrammatical whether we try the form is or are or even am. In (5b) the sentence is ungrammatical even though we have the compound noun baby panda, again no matter what form of the verb we try.

| (5) | a. | *That I saw earlier {is / are / am} very cute. |

| b. | *Of a baby panda {is / are} very cute. |

What distinguishes the grammatical sentences in (1), (2), and (4) from the ungrammatical sentences in (5) is that in (1), (2), and (4) the group of words at the beginning of these sentence are noun phrases (remember that the sentences in (3) were ungrammatical only because they had the wrong agreement inflection). Noun phrases are groups of words that not only contain a noun, but where the noun is the “most important” element in some sense.

By “most important” we mean that it’s the noun that determines an important part of the meaning of the subject, but also that it’s this noun that determines the category of the whole phrase, which determines where the phrase can go in relation to other phrases. The noun is the head of a noun phrase. The head of a phrase also determines what else can go in the phrase; in particular it determines whether the phrase contains an object.

-

-

2.5.5 Tree diagrams

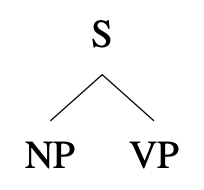

In this section we begin to introduce the formal notation of tree diagrams to represent the structure of phrases and sentences in a way that makes it easier to analyse and test constituency elements about them. What constituents do we find inside sentences? Well, we know that a sentence consists of (at least) a subject and a predicate, that subjects are (usually) noun phrases, and predicates are often verb phrases. We might express this as a rule, known as a phrase structure rule.

S → NP VP

This rule says that wherever you have an S (a sentence), it is possible for that S to be made up of an NP (noun phrase) followed by a VP (a verb phrase).

Another way to represent the same idea is with a tree diagram, as in Figure 23. Tree diagrams can express the same information as phrase structure rules, but can more efficiently express the output of multiple such rules; current syntactic theories are typically expressed in terms of constraints on possible trees, rather than in terms of constraints on phrase structure rules.

Figure 23. Schematic tree for S containing an NP subject and VP predicate by Anderson et al. is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Chapter Attribution

This chapter has been adapted in parts from:

Essentials of Linguistics (2nd edition) by Anderson et al. (2022). Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

-

Syntax is the study of how words are organized into phrases and sentences.