2.8 Language variation and change

2.8.1 Sociolinguistics

Variationist sociolinguistics is a methodological and analytical approach to understanding the relationship between language and its context of use. We call it sociolinguistics because both social and linguistic (e.g., grammatical, structural, articulatory) factors, are equally important; sociolinguistics, unlike many formal approaches to language, does not focus on an idealized grammar (sometimes called ‘competence’) but rather analyzes language in use (sometimes called ‘performance’). We call it variationist sociolinguistics because it’s concerned with the variable nature of language in use.

2.8.2 Language varies

There is substantial variation in language: both within and across language varieties. We’ll see some examples of both of these kinds of variation and introduce one of the central concepts used in variationist sociolinguistics: the linguistic variable.

All languages exhibit variation

Many linguistic approaches to the study of language are concerned with language variation. Theories about how language works rest on evidence that comes about by contrasting the way something is said or signed in two or more different languages, dialects, or varieties.

LANGUAGE, DIALECT AND VARIETY

Colloquially, the term dialect is used to refer to ways of speaking that people perceive to be substandard, low status, associated with working class, non-prestigious, geographically-isolated, or some derivation or aberration from a ‘standard’ version of the language. The linguistic fact though is that everyone has a dialect. Rather than think about languages and dialects in a hierarchical way, linguists think about dialects as subdivisions of a language. Sometimes, linguists might talk about the “standard dialect” but it’s important to emphasize that no dialect, not even what we might call the “standard dialect” is objectively (linguistically) superior to any other dialect of the language. Another term, ‘variety’ doesn’t have the same negative connotations that ‘dialect’ has, and so we’ll usually use that to refer to subdivisions of a language in this chapter.

What’s a linguistic variable?

When we approach language from a variationist sociolingistic perspective, we call the choices between a set of options that mean the same thing a linguistic variable. The individual options that people choose between in the course of language use, we call variants. Linguistic variables exist in all languages and varieties, in all modalities, and at all domains of language from the phonetic to the pragmatic. A linguistic variable is an abstract set; there’s nothing out there in the world that we can point to and be like “hey, that’s a linguistic variable!”. We only ever see or hear the abstract variable as one of its concrete variants. Let’s have a look at some examples of linguistic variables from different languages and different domains of language.

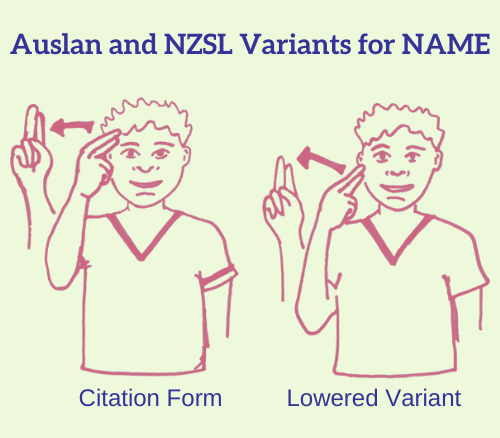

In Auslan, NZSL, and ASL, some signs that are prescriptively located at the forehead, like KNOW, THINK, and NAME, have variable location: at the forehead or lowered to near the cheek (Bayley et al., 2015). You can see these two variants in Auslan/NZSL in Figure 24 and watch a video in ASL. This is an example of phonetic-phonological variation with variants differing with respect to an articulatory parameter (in this case, location).

We also find linguistic variables in the morphophonological domain of languages. Standardized English contains a categorical alternation with the indefinite article between an and a with an occurring prior to a vowel and a occurring elsewhere (cf. an apple vs. a pineapple). However, in contemporary London English, especially among immigrant youth of colour, the pre-vocalic context exhibits variation between an and a; both an apple [ənæpl] and a apple [əʔæpl] are possible (Gabrielatos, Torgersen, Hoffmann, and Fox 2010).

2.8.3 Language conveys more than semantic meaning

All kinds of information about people are revealed through the ways they express themselves linguistically. Much of that information goes beyond the semantic and even pragmatic meaning of the sentences they sign/speak. All kinds of social meanings are revealed through language! Some of this social meaning relates to how language functions in relation to social structures and power. For example, different forms of address – that is, labels we use to refer to our interlocutor – in many different languages reflect the social ranks of those involved in the interaction or the social circumstances of the interlocutor. For example, in Canadian English, referring to someone as sir or buddy reveals several sociological facts including how the speaker perceives the addressee’s gender, how the speaker perceives the power dynamic between themself and the addressee, and how the speaker perceives the formality of the interaction. In fact, language doesn’t just reflect these things but also works to enact this kind of sociocultural significance. Imagine you’re at a café and you witness a dispute between a male-presenting customer and a barista. At first, the barista refers to the customer as sir and says “sir, I know you’re upset but generally we don’t add steamed milk to iced coffees.” But, after a few minutes of being yelled at and insulted by the unruly customer, the barista exclaims “listen buddy, it’s time for you to leave!”. This change in form of address, from sir to buddy, signals a change to the interactional context. The barista signals that they will no longer tolerate being treated poorly and along with that they abandon the general expectation of politeness and formality that comes along with the ‘customer is always right’ mandate of most service work.

Beyond forms of address, many languages encode information about social structure into pronominal reference. Many Indo-European languages make a distinction between familial/informal/lower rank and formal/polite/higher rank second person, singular pronouns. This is often referred to as a T/V distinction on the model of French’s distinction between familial tu and formal vous. Romance languages like French, Slavic languages like Russian, and Germanic languages like German (and even Old and Middle English!) mark this distinction. If you do not know a language that marks this kind of distinction, its social significance may not seem particularly… significant! But for people who do use languages with such distinctions, the real life consequences of language as it relates to social power is clear.

Language can also tell us something about the cultural values of its users. For example, both what we discuss and with who is culturally-determined. What counts as a taboo subject (i.e., an inappropriate topic of discussion) differs by culture and context. In Euro-American culture, it is often considered taboo to talk about sexuality and death around children for example. Connected with this is how we interact: conversational styles (including the amount of interactional overlap, tolerance for interruptions, eye-contact expectations, etc.) are also culturally variable. It’s critical for linguists and language-pathologists to be aware of the culturally-specific nature of interactional norms because too often English and Euro-American norms are interpreted as universals and thus, differences from those norms can be misinterpreted as deficiencies. For example, in their exploratory study of First Nations English, language-pathologists Jessica Ball and B. May Bernhardt (2008) note that where silence from a child is often interpreted as an indication of a lack of knowledge, rudeness, or shyness in Euro-American interactional norms, for many First Nations children, their silence is a sign of respect to elders.

Contextual information is another kind of social meaning that is revealed through language and linguistic variation. Contextual style is intimately connected with the formality of the interactional context. This formality relates to 1) the familiarity of two interlocutors with one another, 2) the social similarity/difference and power relations between them, and 3) the context of the interaction. Conversations between friends who share common experiences and identities are more likely to have a casual style whereas conversations between strangers of unequal social rank and who share little common ground are more likely to be formal. This varies on a continuum. But what do we mean by formal and casual language? There are several aspects of conversation that are linked with formality including the frequency of use of different variants of linguistic variables. Variants that are standardized tend to be more frequent in formal contexts and variants that are not standardized tend to be more frequent in casual contexts.

Chapter Attribution

This chapter has been adapted in parts from:

Essentials of Linguistics (2nd edition) by Anderson et al. (2022). Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.