9.2 Drugs for Anxiety Disorders

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this module, it is expected students should be able to demonstrate and apply knowledge of:

- Nature and symptoms of anxiety disorders

- Pathogenesis of anxiety

- Agents used for anxiety disorders

- GABAA receptor/chloride ion channel

- Benzodiazepines and GABAA receptor

- Barbiturates and GABAA receptor.

Introduction

Anxiety disorder is a group of mental illnesses that relate to physical and emotional symptoms of fear, which is considered as ‘functional psychiatric disorders’ such as anxiety at work or anxiety prior to the exam. Students need to note that anxiety is a part of our daily life however, clinically anxiety disorders are identified when the illness produces significant functional impact. Anxiety symptoms may be associated to other psychiatric (eg depression) or physical disorders (eg hyperthyroidism).

Anxiety disorders are divided into many subgroups, each having unique features including epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical presentation and treatment regimen but also share many of the common features. Examples of anxiety disorders are generalised anxiety disorder, panic disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), acute stress disorder, post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), social phobia and specific phobia (e.g. arachnophobia, ophidiophobia, acrophobia, agoraphonia, etc.).

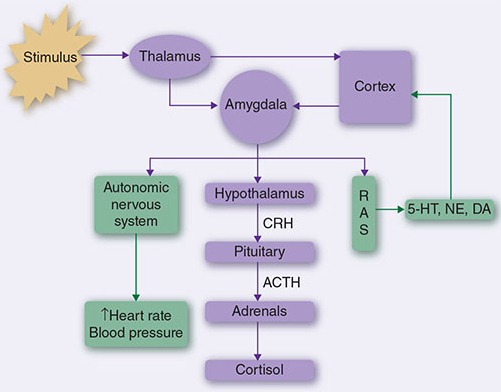

The aetiologies of anxiety disorders are multi-factorial and not fully understood. Different types of anxiety disorder appear to have different aetiology and/or pathophysiology. The epidemiology of anxiety is very difficult to predict, which is mainly affected by variations and non-specific diagnostic criteria(s), culture’s perception and lack of awareness, difference between different types of anxiety disorders and interpretation of “significant functional impact”. Genetic factors exhibit significant risk in developing anxiety disorder, but significant stressors are often observed. Some individuals appear to be resilient to stress, but others can be very vulnerable. Family history appears to be associated with most type of anxiety disorders.

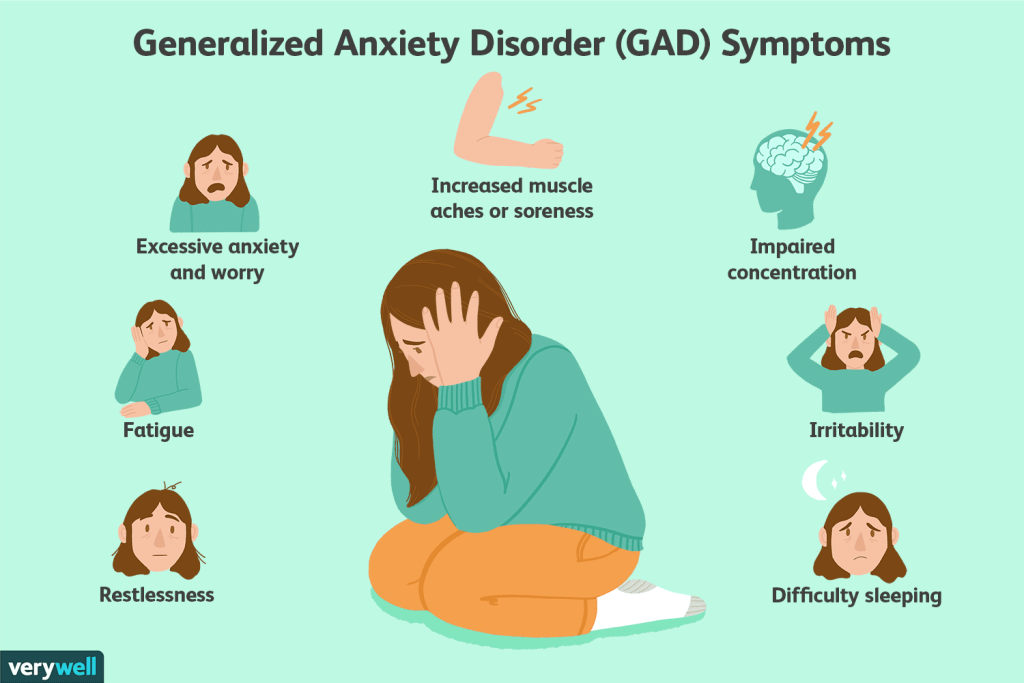

A. Generalised anxiety disorder (GAD) is a long-term disorder. It is very common and affects up to 5% of the population. Diagnostic criteria for GAD include excessive anxiety and pervasive and uncontrollable worry about a number of events or activities, and which occurs for a period of 6 months or longer. Common symptoms of GAD include restlessness, easily fatigue, difficulty concentrating or ‘mind gone blank’, irritability, muscle tension and sleep disturbance.

There is overlap between GAD and other anxiety disorders, and it often coexists with and may mask major depressive disorder and/or dysthymic disorder. Organic factors (eg hyperthyroidism, caffeine intoxication, stimulant use, alcohol/drug discontinuation syndrome) or adverse effects of prescribed drugs or over-the-counter medication must be excluded. An adjustment disorder, as defined in Adjustment disorder with anxious mood, must also be excluded. When middle-aged or older patients first present with anxiety symptoms, exclude depression or dementia as the primary cause of the anxiety symptoms.

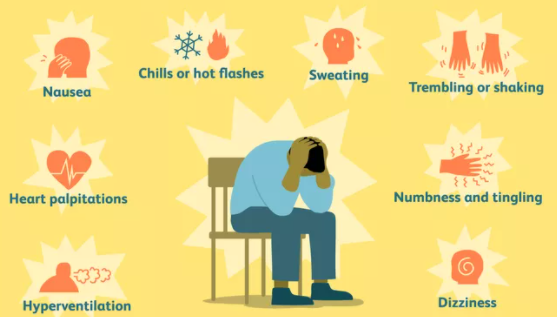

B. Panic disorder is the reoccurrence of sudden onset of symptoms (panic episode/attack), such as fear of dying, fear of change or discomfort which may be presented with psychological induced physical symptoms, such as chest pain and shortness of breath. Care must be taken for clinical assessment to eliminate potential medical causes of the symptoms and or other mental illnesses. Patients who experience multiple panic episodes often develop personality changes e.g., avoidance behaviour, becoming very passive, dependence and withdrawal (social or mental).

Pathogenesis – Panic disorder is strongly associated with genetic predisposition and neurological dysfunction e.g. catechol-O-methyltransferase gene polymorphism, autonomic dysfunction, increased GABA-ergic tone, increased cortisol level etc.

The common stimulants for panic attacks are injury (accident and non-accident) and illness, interpersonal conflict or illness, use of stimulants (caffeine, decongestant, cannabis, cocaine, amphetamine), stimulant of social phobia or specific phobia, sudden treatment withdrawn (e.g. SSRI). Common symptoms include palpitation, sweating, chill, hot flush, shaking, SOB, chest pain, dizziness, headache etc.

C. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) – PTSD is an anxiety disorder develops after the patient is involved in, or has weakness, or was confronted by traumatic events such as injury, death or violation of one’s personal integrity. The severity and duration of PTSD varies widely among individuals. Exposure to traumatic events commonly results in a degree of psychological distress. In most instances, psychological symptoms of distress settle down in the days to weeks following the event. However, a minority of people exposed to traumatic events have persisting symptoms and develop acute stress disorder and/or posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The symptoms of PTSD are divided into 4 main groups – develop the mentality of helplessness, intense fear or horror; experience repeating ‘flush back’, or intense psychological distress when confronted by cues that symbolised the event (e.g. Image, smell, person); avoidance, detachment or numbing response, ‘false amnesia’ of the event; and irritation, sleep disorder, extra vigilant, exaggerated responses. Children may only exhibit irritation or ‘unusual behaviour’, but with different characteristic symptoms at different age groups.

The pathogenesis of PTSD is associated with genetic predisposition, nature and proximity of trauma, prior experience of trauma (esp. during childhood) and posttraumatic factors (e.g. Social and psychological support).

D. Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) – A condition that is characterised by one or more anxiety-provoking ideas, impulses (obsessions) or urges (compulsion), and requires taking specific/repeating actions until ‘it feels right’. These include cleanliness or contamination, safety, doubting one’s memory or perception, scrupulosity (psychological guilt, moral or religious issue), things that need to be arranged/done in a specific order, and intrusive thoughts of sexual or physical aggression. Common symptoms include frequent hand washing, cleaning, checking, hoarding, rituals, avoidance of human interaction, environment or situation.

E. Phobias – There are varieties of phobias including social phobia and specific phobias. The pathogenesis of phobia is not well understood but some phobias are related to genetics, previous exposure to event/trauma, cognitive distortion and neurological dysfunction.

📺 Watch the following lecture on introduction, symptoms and different types of anxiety disorders (18 minutes)

Treatment and management

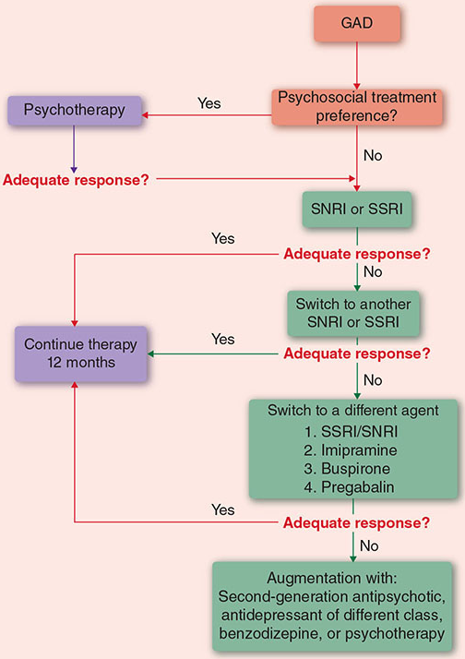

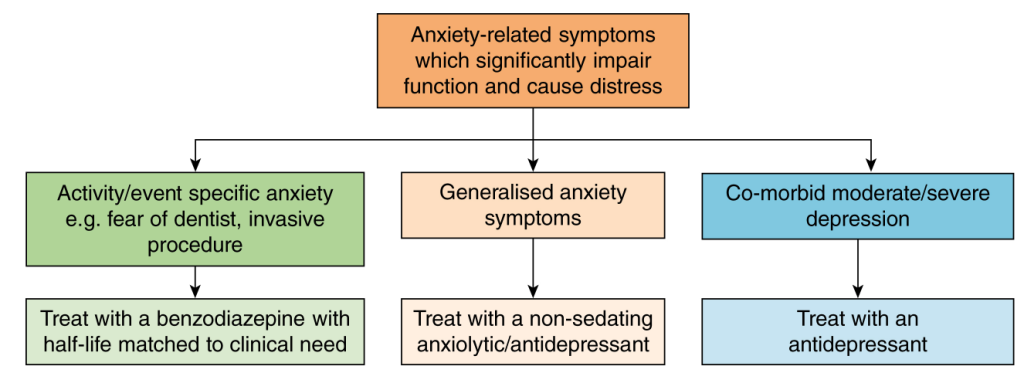

The following general rules for managing anxiety disorders with some variations depending on the nature of the disorder.

1. Identify the precipitating factor(s)

- Avoid or eliminate the factors

- Social support and reassurance may be all that is required.

2. Psychotherapies

- Consider as first line intervention therapy for all anxiety disorders. The psychotherapies are psychological, including counselling, relaxation, problem solving, stress management, and cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT).

3. Pharmacotherapy

Use as an adjunct to psychotherapy is the most recommended therapy for most anxiety disorders.

Solo therapy without psychological intervention is usually not recommended.

Treatment of anxiety disorders requires careful consideration of the individual patient, probable cause and severity of the symptoms. Psychological therapies are important as well as drug treatments and, for most patients, drug treatments alone are unlikely to achieve long-term recovery.

Classes of anxiolytic drugs

- Antidepressant drugs (SSRIs, SNRIs, TCAs and MAOIs, receptor-blocking antidepressants) are effective anxiolytic agents – already discussed

- Benzodiazepines are used for treating acute anxiety and insomnia.

- Gabapentin and pregabalin drugs have anxiolytic properties – will be discussed as Anti-epileptic drugs later

- Buspirone is a 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT)1A-receptor agonist with anxiolytic activity but little sedative effect.

- Some atypical antipsychotic agents (e.g. quetiapine) can be useful to treat some forms of anxiety but have significant unwanted effects.

- β-Adrenoceptor antagonists (e.g. propranolol) are used mainly to reduce physical symptoms of anxiety (tremors, palpitations, etc.); no effect on affective component.

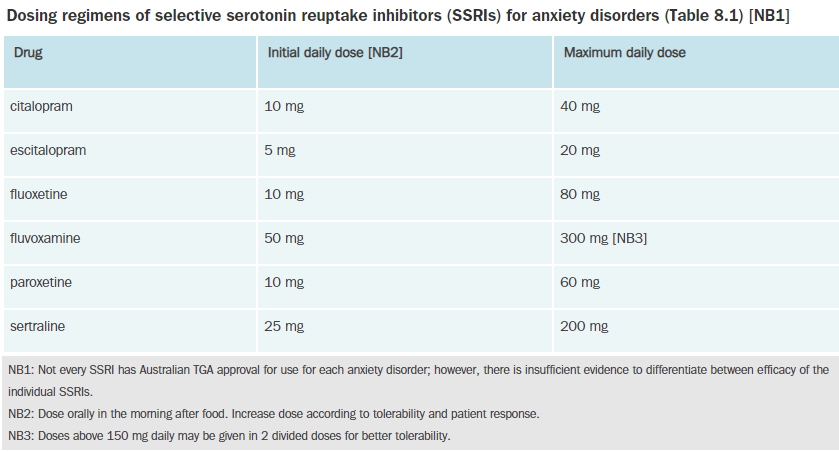

Pharmacotherapy should be commenced from the lower end of the recommended dose. Benzodiazepines (e.g., diazepam) can be given for short term therapy. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs, e.g., sertraline, citalopram, escitalopram) are the most effective pharmacotherapy for GAD and other anxieties. Please note that the antidepressants have already been discussed in the previous lecture.

In addition, the serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors venlafaxine and duloxetine and atypical anti-depressants such as mirtazapine have demonstrated efficacy for GAD. Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs, e.g., amitriptyline) are equally effective but not considered as 1st line due to adverse effects. Buspirone is another choice. Please refer to eTG for more details with dose and frequency.

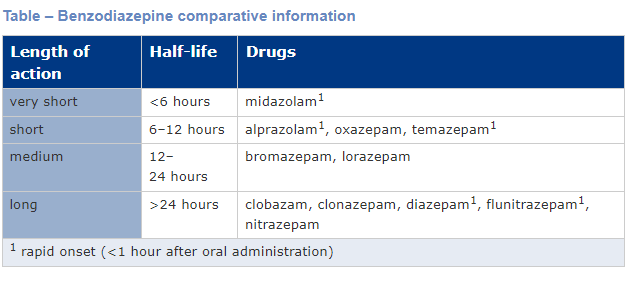

Benzodiazepines and related drugs

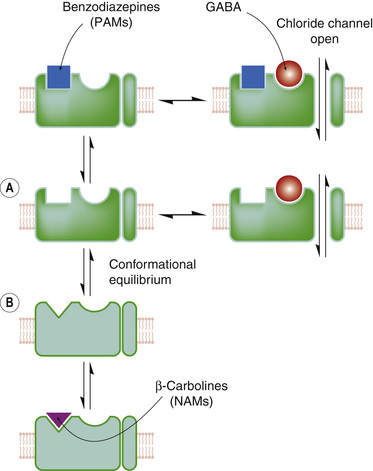

You will need to review the GABAA receptor/chloride ion channel in order to understand how anxiolytics and sedative hypnotics work.

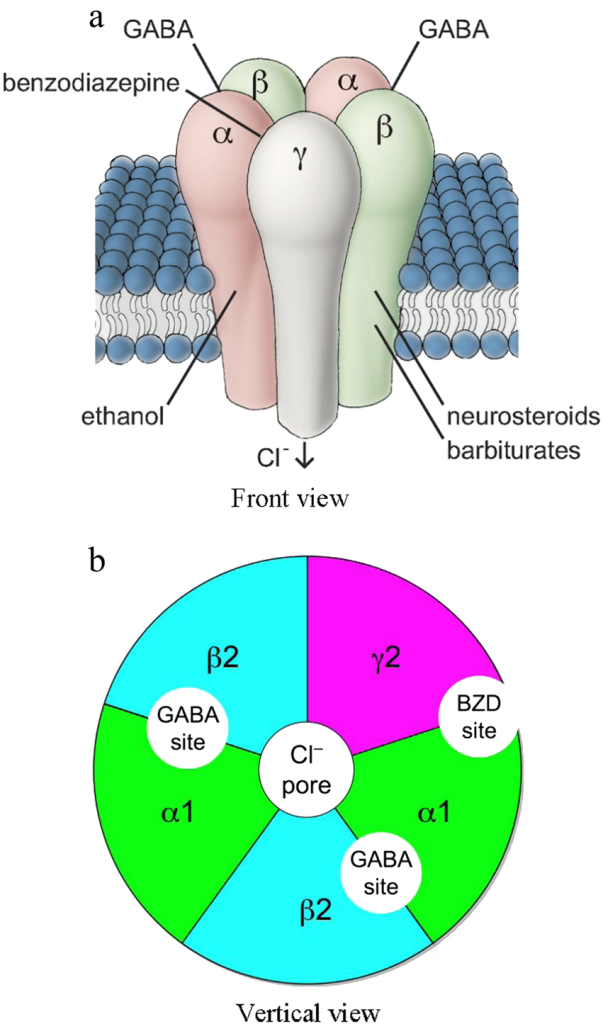

GABA receptors are subdivided into GABAA and GABAB receptors. All GABAA receptors are ligand-gated chloride channels, located in the membranes of postsynaptic cells. It is a very complex receptor system, made up of 5 protein subunits (pentamer) with up to 6 different types (with subtypes) of subunit.

The predominate subunits of GABAA receptors are α, β and γ. The neurotransmitter GABA binds to the interface between the α and the β subunit, on the GABAA receptor. When the GABAA receptor-ionophore complex is activated by GABA there is an increase in chloride permeability and influx of chloride into the cell. This causes hyperpolarisation and decreased excitability of the neuron. This is because GABA is the main inhibitory neurotransmitter in the CNS. GABA is involved in about 30% of all CNS synapses, in many pathways and brain areas. Anxiolytic effects are mediated by GABAA receptors containing the α2 subunit, while sedation occurs through those with the α1 subunit.

GABAA receptors have several modulatory sites at which drugs act. These drugs include benzodiazepines, barbiturates and ‘z drugs’.

📺 Watch the following video on YouTube. The video can be found at https://www.nature.com/articles/s41401-018-0185-5/figures/1

📺 Watch part 1 of the lecture

COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING This material has been reproduced and communicated to you by or on behalf of James Cook University in accordance with section 113P of the Copyright Act 1969 (Act).

The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further reproduction or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice.