10.6 Local Anaesthetics

Local Anaesthetics

Local anaesthetics are used to inhibit pain by local and reversible blockade of sensory nerve conduction. Cocaine was the first local anaesthetic and procaine was the first synthetic isolate of cocaine used for local anaesthesia. Neither are commonly used now due to their unfavourable side effect profile.

The local anaesthetics used in Australia are:

- Bupivacaine

- Cocaine (rarely)

- Levobupivacaine

- Lidocaine (lignocaine)

- Prilocaine

- Ropivacaine

- Tetracaine (amethocaine).

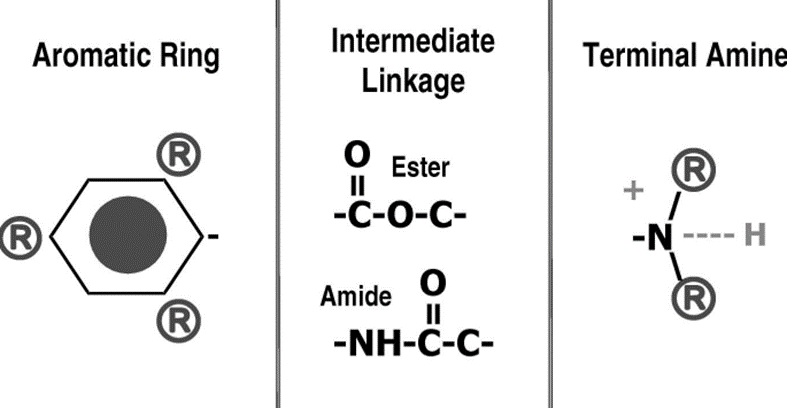

Local anaesthetics share three main components:

- An aromatic group that is lipophilic

- A hydrophilic ester or amide bond that links the aromatic group to the

- Terminal amine that gains a positive charge to become water soluble (or not).

Local Anaesthetics Mechanism of Action

Sodium channels are present in all excitable tissues and are sensitive to changes in the membrane potential of the cell. Sodium channels selectively allow sodium ions to move between the outside and inside of the cell. The sodium channel is made up of 4 domains. Each domain has 6 transmembrane regions arranged to form a pore (where sodium ions are permitted or blocked from movement from one side to the other).

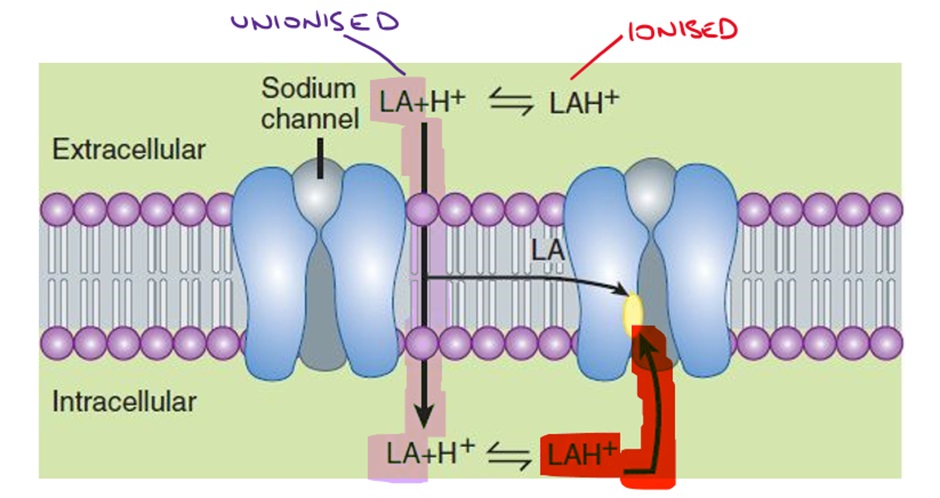

Local anaesthetics (LA) need to move across the epineurium and neuronal membrane to the interior of the neuronal cell to interact with the channel. Binding of the local anaesthetic to the 6th transmembrane region on the 4th domain causes a conformational change in the channel, blocking the movement of sodium ions through the sodium channel.

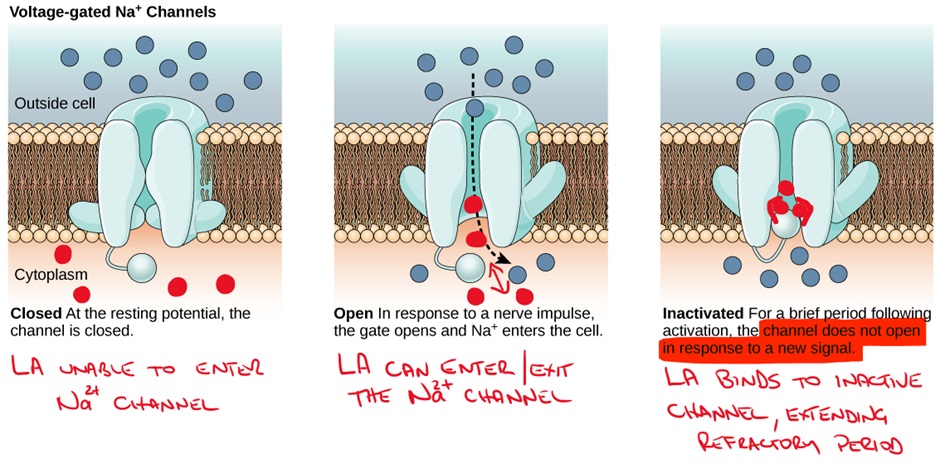

LA entry to the sodium channel is greatest when the channel is open (remember sodium channels exist in open, inactive and resting/closed states). LAs then preferentially bind to the channel in the inactivated state and maintain the inactive (refractory) state.

The effects of LAs are increased when the channel is rapidly cycling between open, inactive and closed states. We know that LAs enter sodium channels during the open state, but they can also exit (dissociate) during the open state if the channel remains open. In contrast, a highly active channel will ‘trap’ the LA in the channel by beginning to inactivate while the LA is still present in the channel and the LA will then bind to the inactive channel conformation prolonging the refractory period.

This is known as “use dependence” – remember this from Class I antiarrhythmics.

Impact of pH on local anaesthetics

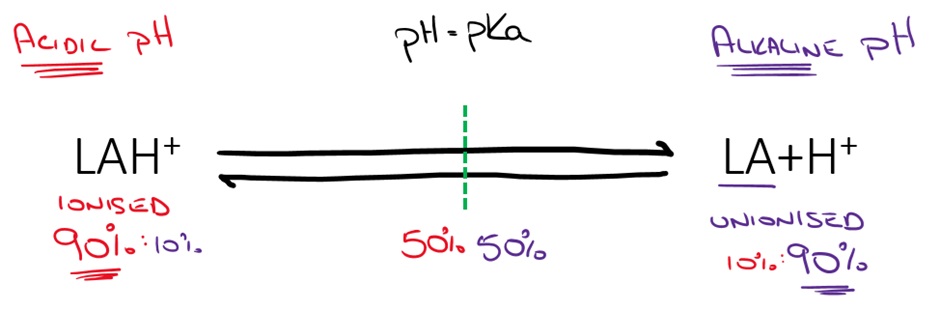

pH is an important consideration when using LAs. LAs are basic drugs which have a pKa close to physiological pH of 7.4.

The ionised form (more likely at lower pH) is hydrophilic and therefore increases solubility and shelf life of the LA and is more readily able to enter the sodium channel. LA solutions are prepared and shipped at acidic pH because of the improved solubility and stability. Some of the stinging associated with LA injection may be related to the acidic pH of the solution (remember that pH can trigger nociceptors).

The unionised form (more likely at higher pH) is lipophilic and able to cross cell membranes (epineurium and neuronal membrane). This is important because LAs must enter the cell to have their effect on the sodium channel.

During injury and inflammation, the pH of tissue is decreased which therefore reduces the amount of unionised LA that can cross the cell membrane. This can result in LAs taking significantly longer to take effect and/or reducing the efficacy of LAs.

📚 Read/Explore

Side effects of local anaesthetics

Pain associated with infiltrative LA administration is the most common side effect. As discussed above, alkalisation of the LA solution can reduce this pain in some circumstances.

Cardiac and central nervous system effects can also occur if sufficient LA is absorbed systemically, these can be life threatening. Systemic toxicity is most likely to occur when LA is inadvertently given intravenously, large doses are given, administered into highly vascularised tissue or in children. To counteract this risk, good injection technique is vital.

Additionally, LAs are often administered in combination with adrenaline to produce local vasoconstriction which limits systemic absorption. This provides two advantages, firstly it prolongs the duration of action of the local anaesthetic and secondly it may reduce the risk of toxicity.

🎥 Watch this video

COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING This material has been reproduced and communicated to you by or on behalf of James Cook University in accordance with section 113P of the Copyright Act 1969 (Act).

The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further reproduction or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice.