11.2 Bipolar Disorder

Bipolar Disorder

Introduction

Bipolar disorder involves the occurrence of one or more manic or hypomanic episodes, often alongside a history of major depressive episodes. It is a long-term condition marked by recurring episodes and periods of remission. Mood disturbances may present as mania, hypomania, or depression, and these episodes can include specific features, such as mixed moods. The duration between episodes may vary, ranging from extended periods of stability to rapid cycling, and they may occur with or without psychotic symptoms. The impact on individuals and their families can be severe, leading to significant disability and an elevated risk of suicide. Early and accurate diagnosis, along with appropriate treatment, is critical to avoiding complications and achieving the best treatment outcomes.

The onset of bipolar disorder typically occurs in the late 20s, which is around 15 years earlier than the onset of unipolar depression. However, it can also manifest during adolescence. In individuals who are predisposed, mania may be triggered by a variety of medications, such as antidepressants, corticosteroids, ACE inhibitors, dopaminergic drugs, as well as by certain stimulant and illicit substances.

Acute Mania

Acute mania is characterized by a sudden onset of symptoms, including a persistently elevated, expansive, or irritable mood, along with rapid speech, racing thoughts, and an increase in activity levels. Individuals often require less sleep, may develop grandiose ideas, engage in risky behaviours like excessive spending, and experience heightened sexual drive and activity. When psychotic symptoms are present, the episode is considered severe. For a diagnosis of mania, symptoms must be evident for most of the day, cause significant functional impairment, and last for at least a week. However, if hospitalization is necessary due to the severity of symptoms, a diagnosis can be made regardless of symptom duration.

Hypomanic Episodes

A hypomanic episode shares many symptoms with a manic episode, but the symptoms are less intense and do not significantly disrupt daily functioning. These symptoms typically persist for a minimum of four consecutive days and are present for the majority of each day. Unlike mania, hypomania does not involve psychotic features.

Depressive Episodes

Depressive episodes last for at least 2 weeks and must include a depressed mood, or a loss of interest or pleasure, for most of the day. The episode must cause significant distress or impair the person’s functioning; during depressive episodes, there is a high risk of suicide. While most symptoms overlap with those of major depression, patients with bipolar depression are more likely to have atypical depressive features (eg excessive sleeping or eating), psychomotor slowing, psychotic features or mixed features (ie manic or hypomanic features interspersed in the depression). Most patients experience at least one depressive episode before developing a first episode of mania or hypomania. Depressive episodes are the predominant mood episode for most patients with bipolar disorder, especially those with bipolar II disorder. Patients with bipolar disorder also frequently experience periods of subthreshold depressive symptoms between the major mood episodes.

Mixed features describes the simultaneous experience of symptoms opposite to the predominant state (eg during a manic episode, patients also experience depressive symptoms). Mixed features can occur during a manic, hypomanic or depressive episode.

Bipolar Subtypes

Bipolar disorders are divided into several categories, including bipolar I disorder, bipolar II disorder, and other specified or unspecified bipolar and related disorders. Bipolar I disorder is defined by the presence of at least one manic episode, while bipolar II disorder is characterized by at least one hypomanic episode, with both types typically involving major depressive episodes.

Symptoms during manic episode

Mania is marked by excessive speech and motor activity, a decreased need for sleep, grandiose or paranoid thoughts, elevated or irritable mood, impaired judgement, aggressive behavior, and hostility. It may also involve reckless spending and, at times, promiscuity. In the less severe state of hypomania, individuals may face social difficulties, such as heightened activity levels, unfinished tasks, irritability, wearing overly bright or messy clothing, poor decision-making, and an increase in sexual interest. Individuals with bipolar disorder can subsequently experience a shift to depression, which may last for several months.

Treatment of Bipolar Disorder

Counselling, psychotherapy and drug therapy are beneficial for treating bipolar disorders. The main class of drugs used to manage the symptoms of bipolar disorder are the mood stabilisers. The major drugs are:

- lithium;

- certain antiepileptic drugs, e.g. carbamazepine, valproate, lamotrigine; and

- some antipsychotic drugs (second generation), e.g. olanzapine, risperidone, quetiapine, aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, cariprazine.

Certain other agents may offer benefits in managing bipolar disorder. Benzodiazepines can help by promoting calmness, sleep, and reducing anxiety. Memantine and amantadine have potential to alleviate depression and cognitive issues, while ketamine may be useful for addressing suicidal thoughts. The use of antidepressants in bipolar disorder remains debated, as they are typically prescribed alongside antimanic medications. This is because, in some individuals, antidepressants may trigger or intensify manic episodes. Antipsychotic drugs, benzodiazepines and some antiepileptic drugs are useful for sedation and control of the mania symptoms, and antidepressants with lithium in the depressive phases for at least 6 months.

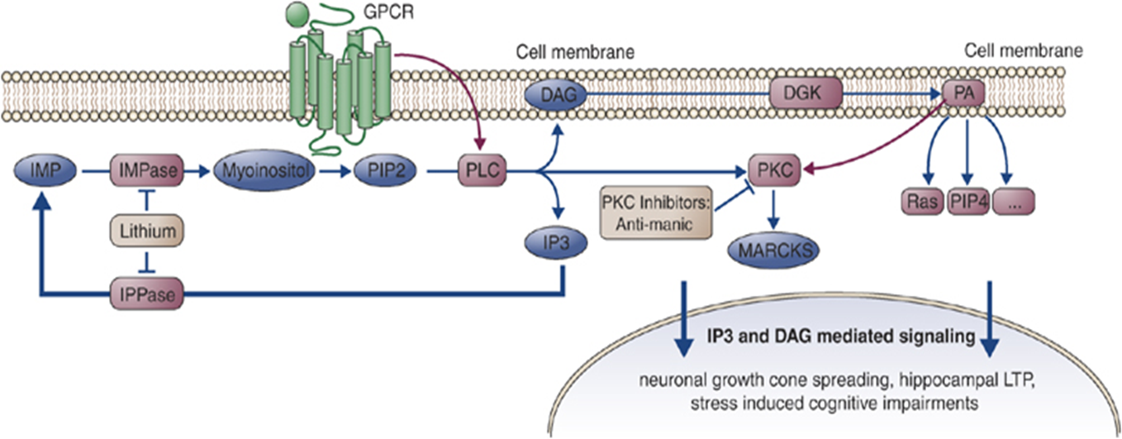

Lithium

Lithium is also known as a mood stabiliser. It is used as first-line treatment for acute mania and prevention of recurrences of manic episodes.

👁️🎧 Listen & Watch the Lecture on Drugs for Bipolar Disorder (10 minutes)

Lecture Material:

COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING This material has been reproduced and communicated to you by or on behalf of James Cook University in accordance with section 113P of the Copyright Act 1969 (Act).

The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further reproduction or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice.