2.6 Management of High Blood Pressure

John Smithson

Management of High Blood Pressure

For Primary Hypertension, all patients are treated with non-drug interventions. So when do we begin to treat with drug therapy?

- Once diagnosis is confirmed on at least 2 separate occasions (remember – measurements taken 1 week apart), start treatment straight away if there is a high cardiovascular risk, either:

-

- Because that’s the calculated risk assessment, or

- Because the patient is considered automatically at high risk

- Once diagnosis is confirmed on at least 2 separate occasions, start treatment straight away if there is a moderate cardiovascular risk, and:

-

- BP persistently ≥ 160/100mmHg, or

- Family history of premature CVD, or

- The patient identifies as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander

- Once diagnosis is confirmed on at least 2 separate occasions, start treatment straight away if there is a low cardiovascular risk, and:

-

- BP persistently ≥ 160/100mmHg

If treatment is not started straight away, the patient should be provided with lifestyle advice, and there should be a plan for follow up within the recommended period of time.

Blood Pressure Targets

Although precise targets in different population groups (or different people with different comorbidities) are debatable, what we do know is that everyone should at least be treated with a theoretical target blood pressure of less than 140/90.

We might consider targets lower than that if the patient is at a high cardiovascular risk but only if these lower blood pressures are deemed safe on clinical grounds. For example, we wouldn’t take an aggressive approach to reduction of blood pressure in a frail female of advanced age who is prone to falls. We’ll also only consider lower targets if drug therapy is well tolerated. That is, if the patient does not experience any adverse effects associated with the antihypertensives used to reach that lower target (like hypotension, syncope/fainting, electrolyte abnormalities, or acute kidney injury).

In practice, we sometimes struggle to get some patients’ BP down even to 140/90, despite combining several different antihypertensive treatment options. In these cases, we can be reassured that even if we don’t reach our target of 140/90, just moving the BP down towards it will help to improve the patient’s outcomes.

Clinical tips

- For patients who require BP-lowering therapy, aim to reduce BP below 140/90 mmHg

- In patients with high atherosclerotic CV disease risk, lowering BP to below 130/80 mmHg reduces cardiovascular morbidity and may reduce mortality.

Non-Drug Treatment

Remember the ‘SNAP’ risk factors. The non-pharmacological therapy aims to target the SNAP risk factors for disease.

- Smoking cessation – has been shown to reduce blood pressure and overall CVD risk. The risk of smoking on CVD risk declines dramatically over the next 2-6 years to a level comparable to a non-smoker.

Weight control can assist with blood pressure management. A number of studies have associated weight loss with systolic and diastolic blood pressure reduction. A weight reduction of 1 kilogram was associated with lowering systolic and diastolic blood pressure by an average of 1 mmHg. Weight reduction can be achieved through Nutrition modification, reduction or elimination of alcohol and increased physical activity

- Nutrition / diet – there is a relationship between sodium intake and blood pressure. Sodium restriction is shown to lower systolic and diastolic blood pressure particulary in patients with hypertension. Low sodium intake diets are associated with reductions in blood pressure. Consumption of a diet that emphasises intake of vegetables, fruits and whole grains, low fat diary, combined with exercise and weight loss can reduce blood pressure.

- Alcohol – the consumption of 2 or more standard drinks a day for health men and women can immediately increase blood pressure. Consumption of ≥ 2 standard alcoholic drinks for men and ≥ 1 standard alcoholic drinks for women per day increases the risk of developing hypertension.

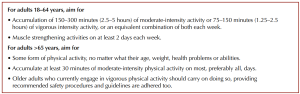

- Physical activity – there is strong evidence that regular physical exercise and moderate to high levels of cardiorespiratory fitness protect against hypertension. Australian guidelines for patients with hypertension advocate for 30-60 minutes of moderate-intensity activity or 15-30 minutes of vigorous intensity activity 5 days a week, every week plus muscle strengthening activities on at least 2 days each week. For adults > 65 years, aim for 30 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity on most or all days.

Motivational interviewing techniques can increase the uptake on non-drug recommentations

Telling patients to make changes typically yields low levels of long-term change. Using the basic skills of motivational interviewing to effect sustained change. The acronym OARS reflects the basic skills of motivational interviewing. You can read more about OARS:

- Ask Open-ended questions

- Make Affirmations

- Use Reflections

- Use Summarising

If you want to learn more, have a look at an excellent article on motivational interviewing techniques written by Dan Lubman, Kate Hall and Tania Gibbie in 2012. (Lubman, d., Hall, K., and Biggie, T. 2012. Motivational interviewing techniques. Facilitating behaviour change in the general practice setting. Volume 41: Issue 9. 2012. Available at [RACGP – Motivational interviewing techniques – facilitating behaviour change in the general practice setting].

AFP-Sep-2012-Motivational-interviewing-techniques can be accessed here.

Antihypertensive Drug Therapy

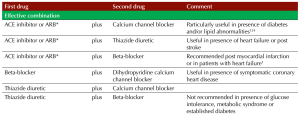

First-line drug classes have similar efficacy in reducing blood pressure. Usually, treatment is started with a low-to-moderate dose of the first chosen antihypertensive. That will be continued for approximately 3 months, and if the target BP is not reached in that time, then a low-moderate dose of a second drug from a different class will be added. This will help to maximise antihypertensive effect while minimising adverse effects associated with a single agent.

The initial drug choice should be a patient-centred decision, that includes consideration of the patient’s comorbidities, any potential for interactions with other drugs the patient is taking, the recommending dosing frequency (as OD dosing may lead to better adherence than multiple-daily dosing), cost, and patient preference too.

Combining antihypertensives is indicated if the target BP is not reached 3 months after starting the initial anti-hypertensive.

What are the drug targets for lowering blood pressure?

The five most important drug targets for lowering elevated blood pressure are:

- Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System (RAAS):

- Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme (ACE) Inhibitors: These drugs inhibit the conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II, a potent vasoconstrictor, thus lowering blood pressure.

- Angiotensin II Receptor Blockers (ARBs): These drugs block the action of angiotensin II on its receptors, preventing vasoconstriction and aldosterone secretion, thereby lowering blood pressure.

- Calcium Channels:

- Calcium Channel Blockers (CCBs): These drugs inhibit the influx of calcium ions into vascular smooth muscle cells, leading to vasodilation and reduced blood pressure. They are particularly effective in lowering blood pressure by relaxing the blood vessels.

- Sympathetic Nervous System:

- Beta-Blockers: These drugs block beta-adrenergic receptors, reducing the heart rate and the force of heart contractions, leading to a decrease in blood pressure. They also reduce the release of renin from the kidneys, which is part of the RAAS.

- Diuretics:

- Thiazide Diuretics: These drugs increase the excretion of sodium and water by the kidneys, reducing blood volume and thereby lowering blood pressure. They are often used as the first-line treatment for hypertension.

- Aldosterone Receptors:

- Aldosterone Antagonists (e.g., Spironolactone): These drugs block the action of aldosterone, a hormone that promotes sodium and water retention, which increases blood volume and blood pressure. By antagonizing aldosterone, these drugs help to lower blood pressure.

Each of these drug targets plays a crucial role in the complex regulation of blood pressure and is used in various combinations to achieve optimal blood pressure control in patients with hypertension.

Up until now, you have learned about blood pressure regulation, the causes and epidemiology of high blood pressure, assessing patient risk for CVD, non-drug and drug management options and the major drug targets. Next, look at the detailed pharmacology of the drugs used to reduce blood pressure.

Suitable first line drug classes for non-pregnant adults are:

- Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) or Angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs). Drugs ending in ‘pril’ are ACE inhibitors, those ending in ‘sartan’ are A2RBs.

- Captopril

- Enalapril

- Fosinopril

- Lisinopril

- Perindopril

- Quinapril

- Ramapril

- Trandolapril

- Candesartan

- Eprosartan

- Erpesartan

- Losartan

- Olmersartan

- Telmisartan

- Valsartan

- Dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers (CCBs)

- Amlodipine

- Felodipine

- Lercandidipine

- Nifedipine (modified release)

- Thiazide diuretics

- Chlortalidone

- Hydrochlorothiazide

- Indapamide.

COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING

This material has been reproduced and communicated to you by or on behalf of James Cook University in accordance with section 113P of the Copyright Act 1969 (Act).

The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further reproduction or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice.