4.2 Drugs for Acute Coronary Syndrome (ACS)

Robi Islam

Acute Coronary Syndrome

Introduction

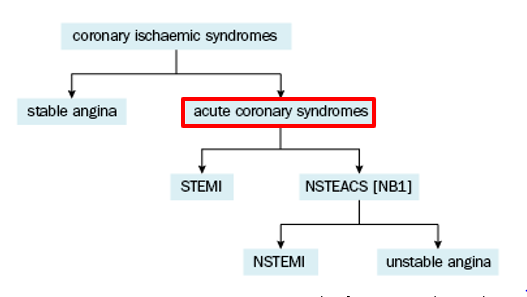

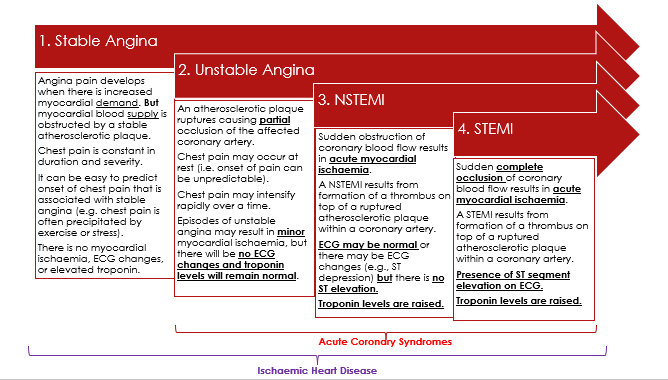

As you learnt last week in heart failure and angina, ischaemic heart disease is an umbrella term that includes a spectrum of disorders ranging from chronic stable angina through to unstable angina and myocardial infarctions (also known as heart attacks).

Patients with stable angina have chronic, stable symptoms. In contrast, acute coronary syndromes are situations where there are new or worsening symptoms associated with a sudden obstruction of coronary blood flow.

The acute coronary syndromes comprise:

- NSTEACS (Non-ST segment Elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes) which is further subclassified into:

- Unstable angina

- NSTEMI (Non-ST-segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction)

- STEMI (ST-segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction)

It is also important to remember that the IHD spectrum can be progressive. For example, unstable angina can progress to a NSTEMI which can progress suddenly to a STEMI.

Figure 4.2.1: Classification of coronary ischaemic syndromes. Source: Modified from eTG Cardiovascular

|

Figure 4.2.2: Image adapted from: https://canadiem.org/acute-coronary-syndrome-beyond-door-to-balloon/ |

All of the diagnoses summarised above involve some degree of myocardial ischaemia. It is the extent and severity of the ischaemia that differs. As we progress to the right of the diagram, the ischaemia becomes more severe and lasts longer. When the ischaemia is severe and persistent enough to cause permanent damage to the myocardium, the result is a myocardial infarction of some type (NSTEMI or STEMI & we’ll discuss the differences later in this module). Such major cardiovascular events can result in cardiac arrest and death. If the person does survive, they may be left with impaired heart function, for example, a diagnosis of heart failure and/or a dysrhythmia.

📺 Watch the video “What is a heart attack?” (1.51 minutes)

👁️ Watch the following video for a patient-friendly representation of the information summarised above. It is also available at https://youtu.be/p6RJvWMgy5w.

📺 Watch the video: Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) – Part 1 (14 minutes)

- Watch the following lecture video for a more comprehensive introduction to the acute coronary syndromes, prevalence, prognosis, pathophysiology and clinical presentation of ACS.

Diagnostic Tests

When it comes to diagnosis, the clinical presentation will be important. There will often be key diagnostic factors like central crushing chest pain as well as other symptoms like dyspnoea or nausea/vomiting. However, there will also be an assessment of the patient’s atherosclerotic risk factors, which were discussed last week. For example, the physician will consider if the patient has hypertension, dyslipidaemia, diabetes, if they are a smoker, if they have a family history of heart disease, and so on.

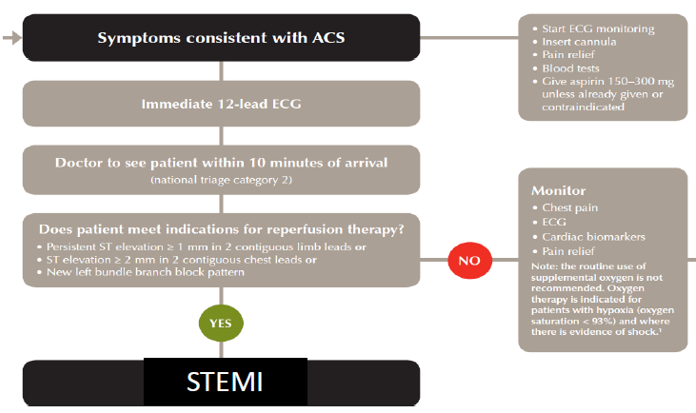

Once all of that has been considered, the key investigations that follow will be an electrocardiogram (ECG) and a blood test that includes an order for cardiac biomarkers (i.e., a high-sensitivity troponin assay).

.

|

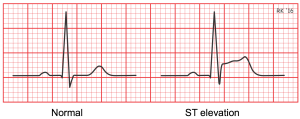

The Electrocardiogram (ECG):

As soon as an acute coronary syndrome is suspected (even if there is only a tiny bit of suspicion that the patient might be having an acute coronary event), the patient will receive a 12-lead ECG. That will be reviewed by an experienced physician within 10 minutes of the patient’s presentation to an emergency department.

The ECG will be repeated every 10-15 minutes generally until the patient is pain-free and a cardiologist has approved cessation of the ECG monitoring. Telemetry may be an alternative to serial ECG monitoring. Telemetry is continuous monitoring of a patient’s heart rate and rhythm.

The most important ECG change that ED physician is looking for is ST segment elevation. This is so important because it plays a large role in dictating the treatment protocol the patient receives. For example, for patients with ST elevation, there is a proven benefit associated with using immediate reperfusion therapy (either by fibrinolytic medication or by percutaneous coronary intervention with stenting). In contrast, fibrinolytic medication is not used if there is no ST-segment elevation on the ECG.

Figure 4.2.4: Source: https://www.cvphysiology.com/uploads/images/CAD012%20ST%20elevation.png |

Cardiac Troponins:

Troponin is a protein that lives in myocardial cells. There are different types (TnC, TnI, and TnT), but TnI is most commonly used for diagnosing ACS. Raised levels of troponin in the blood signifies myocardial injury. In October 2018, Queensland Health hospitals introduced a new high-sensitivity cardiac troponin assay. This new assay can reliably detect circulating troponin at lower levels.

Historically, troponin levels were checked on presentation and then again 6-hours later (i.e., at 0 and 6 hours). Now, troponin levels are checked on presentation and then again 3-hours later (i.e., at 0 and 3 hours). If troponin levels return normal on both occasions, it is unlikely that the person has had a myocardial infarction.

- If a patient has had a myocardial infarction, after approximately 3 hours have elapsed, you would expect troponin levels to be higher than they were at the initial presentation. This is because TnI leaks out of myocardial cells slowly. TnI also persists in the bloodstream for anywhere between 4 and 7 days, which makes it difficult for us to use TnI to diagnose a second myocardial infarction within 7 days of the first one!

- It is also important to note that the turn-around time (the time it takes for the troponin result to be returned from the laboratory) can be variable (up to approximately 50 minutes). So…. if there is ST elevation on the ECG, troponin will be tested and it will be positive, but we don’t wait for the blood to be collected and for the troponin results to return from the lab before reacting to the ST elevation seen on the ECG trace. That is to say, cardiac biomarkers are not necessary to confirm the diagnosis of STEMI. Troponin levels are, however, necessary to differentiate the NSTEACS (i.e. NSTEMI vs. unstable angina). Raised troponin levels will confirm the diagnosis of NSTEMI.

Initial Management of Suspected ACS

Summary

Time is heart muscle (and mortality) !! First steps:

- Seek medical help, call an ambulance!

- Paramedics will:

- Notify hospital emergency department of impending arrival

- 12 lead ECG

- Monitor vital signs

- E.g. blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, temperature, etc.

- Give aspirin 300mg orally (chewed or dissolved) unless contraindicated

- Give sublingual GTN spray 400micrograms every 5 minutes if pain persists

- Up to a total of 3 doses if tolerated

- Give an intravenous opioid if necessary for persistent chest pain

- E.g. morphine 2.5 – 5mg IV every 5 – 10 minutes if necessary (monitor sedation score and blood pressure)

- Give oxygen (only if necessary, i.e., if the patient’s oxygen saturation is less than 94%)

📺 Watch the video: Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) – Part 2 (9 minutes)

- Watch the following lecture for a brief diagnostic tests (ECG & troponin), and the initial management of a suspected ACS.

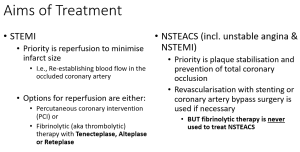

Part 2: Management of STEMI & NSTEACS

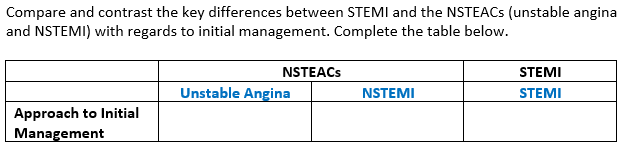

There are important differences when it comes to the management of a STEMI and the NSTEACS (unstable angina or NSTEMI). These are directly related to the aims of treatment.

|

Part 2a) Acute Management of STEMI:

For patients with a confirmed STEMI who have presented to the emergency department within 12 hours of symptom onset, emergency reperfusion therapy is indicated.

- Note that ‘percutaneous coronary intervention’ is commonly abbreviated to ‘PCI’. This is synonymous with ‘percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty’ or ‘PTCA’ that was introduced in last week’s lecture on the possible surgical management of stable angina. Watch the video below for a reminder about what this is referring to (1.08 mins).

📺 Watch the video “Percutaneous coronary intervention stenting” – (1.08 minutes)

Fibrinolysis is the use of an intravenous medication (Tenecteplase, Reteplase, or Alteplase) that works to dissolve the clot that has formed in the coronary artery. The pharmacology of these thrombolytics will be discussed in the week 5 lecture on anticoagulation.

“For the purposes of reperfusion therapy, PCI is preferred over fibrinolysis if it can be performed within 90 minutes of the first medical contact. Otherwise, fibrinolytic therapy is preferred for those without contraindications.” Source: National Heart Foundation of Australia & Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand. Australian Clinical Guidelines for the Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes 2016.

Note the following contraindications to fibrinolytic therapy (not an exhaustive list, consult product information, and note that each patient requires individual assessment with regards to risk vs benefit of proceeding with thrombolysis).

- Known hypersensitivity (allergy) to the active ingredient or to gentamicin (a trace residue from the manufacturing process)

- Active bleeding (excluding menses) or significant bleeding disorder

- Severe thrombocytopenia

- Prior intracranial or subarachnoid haemorrhage

- A structural cerebrovascular lesion (e.g., arterial aneurysm or arteriovenous malformation)

- Malignant intracranial neoplasm (primary or metastatic)

- Ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack (TIA) within the previous 6 months

- Severe uncontrolled hypertension (i.e., BP >180/110mmHg)

- Trauma or major surgery (especially involving the head and/or face) within the previous 3 months

- Non-compressible vascular punctures in the past24 hours (e.g., lumbar puncture)

- Suspected aortic dissection

- Severe hepatic dysfunction, including hepatic failure, cirrhosis, portal hypertension, and active hepatitis

- Active peptic ulcer within the previous 3 months

- Prolonged or traumatic CPR (> 2 minutes) within the previous 10 days

- Current therapeutic anticoagulation for another indication

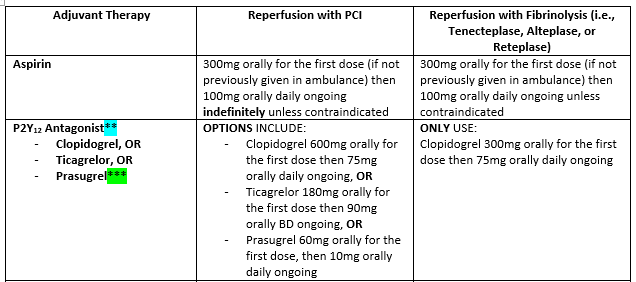

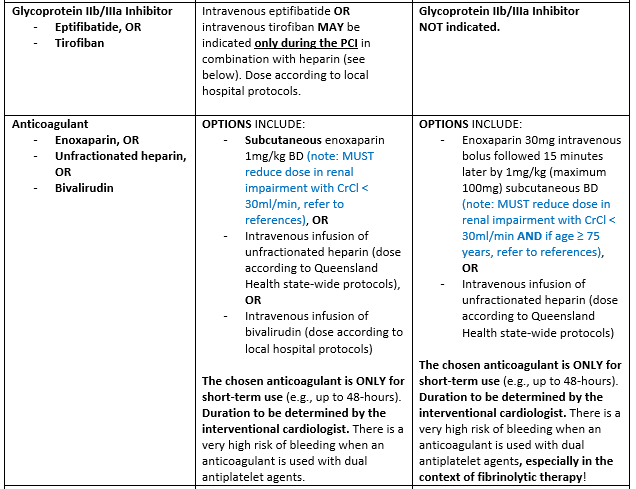

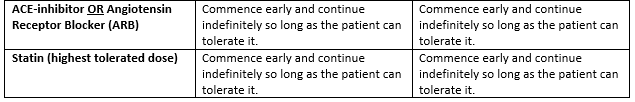

Early management of a STEMI also includes adjuvants to reperfusion therapy.

📺 Watch the following lecture video (21 minutes) for the management of STEMI including the aims of treatment.

Part 2b) Acute Management of NSTEACS:

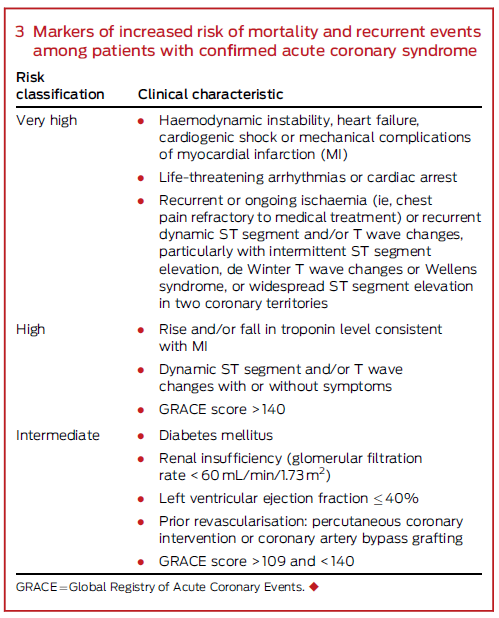

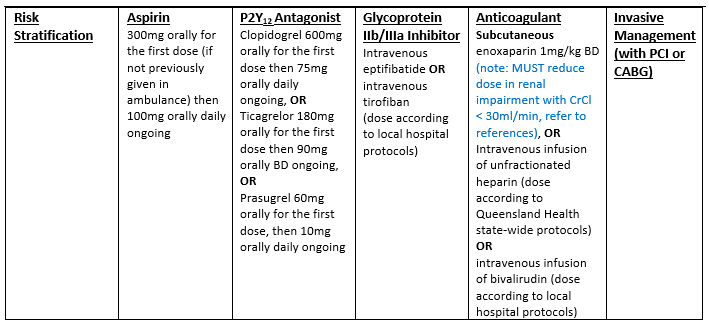

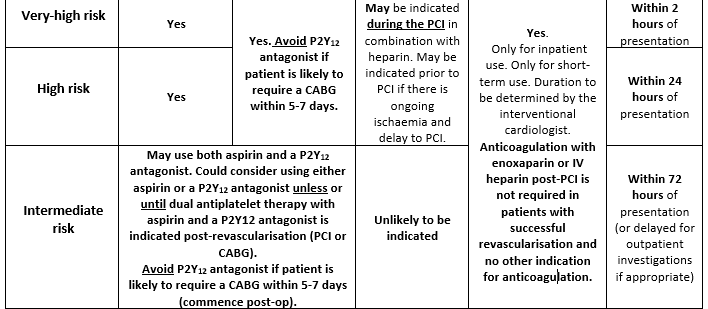

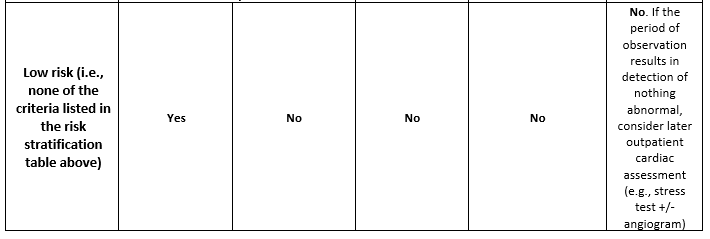

Management of the NSTEACS is a little bit more complicated than management of STEMIs. Unstable angina and the NSTEMI are considered a continuum and both are treated under the overarching term that is NSTEACS. The chosen treatment regimen depends on an initial risk assessment. Patients with confirmed NSTEACS are classified as having either a very high, high, or intermediate acute risk of a recurrent cardiovascular event and mortality.

- Very high-, high-, and intermediate-risk criteria are listed in the table below.

|

Figure 4.2.5: Source: Chew DP, Scott IA, Cullen L, et al. Guideline Summary National Heart Foundation of Australia & Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand. Australian Clinical Guidelines for the Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes 2016. MJA. 2016;205(3):128-133.

|

Specifically, this risk assessment determines when a patient with confirmed NSTEACS should undergo invasive management with PCI or CABG. Remember that fibrinolytic therapy is NEVER used to treat NSTEACS.

- Very high risk = PCI or CABG recommended within 2 hours of presentation

- High risk = PCI or CABG recommended within 24 hours of presentation

- Intermediate risk = PCI or CABG recommended within 72 hours of presentation, but angiography may be delayed and completed post-discharge if this is deemed clinically and logistically appropriate by the cardiologist in consultation with the patient and their family

Note that the GRACE score is an estimate of mortality after NSTEACS or STEMI. If you are interested, you can access an online GRACE score calculator or at https://qxmd.com/calculate/calculator_262/grace. There is no need for you to have a comprehensive understanding of the GRACE score.

A summary of NSTEACS management is outlined in the table below:

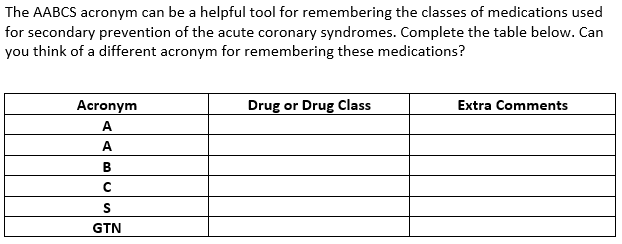

- Aspirin

- 100mg orally daily indefinitely

- Unless contraindicated, e.g., due to hypersensitivity

- ACE Inhibitor orAngiotensin Receptor Blocker

- Titrate dose according to response (BP) and tolerability

- Especially beneficial for patients with co-existent hypertension, left ventricular systolic dysfunction, and/or diabetes

- Beta Blocker

- Most of the evidence for starting a beta blocker post-ACS pre-dates current revascularisation techniques (i.e. it is outdated and doesn’t really apply to current practice)

- May optimise beta blocker dose as part of anti-anginal regimen if diagnosis is unstable angina (esp. if patient is not for revascularisation with PCI or CABG)

- Otherwise, only recommended for patients with reduced left ventricular systolic function (ejection fraction ≤ 40%) post-myocardial infarction. In these cases, only use a vasodilatory beta blocker (i.e., carvedilol, nebivolol, bisoprolol, or extended-release metoprolol).

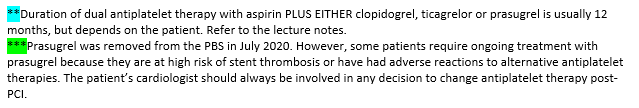

- P2Y12 Antagonist: Clopidogrel, Ticagrelor, or Prasugrel

- Use as an alternative to aspirin if aspirin is contraindicated

- Use in addition to aspirin for up to 12 months post-ACS (regardless of whether revascularisation was performed but especially if PCI + stenting was performed)

- Statins

- Start the highest tolerated dose and continue indefinitely

- Start by targeting a LDL-cholesterol level of < 1.8mmol/L

- But the lower the cholesterol level the better, there is no apparent lower limit

- Sublingual GTN

- To continue PRN use

- Referral to a cardiac rehabilitation service

📺 Watch the following lecture (15 minutes) for the management of NSTEACS (both unstable angina and NSTEMI) as well as long-term secondary prevention of ACS

🔍Compare/contrast

|

|

Key Resources for Further Reading

- National Heart Foundation of Australia &Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand. Australian Clinical Guidelines for the Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes 2016. National Heart Foundation website. https://www.heartfoundation.org.au/getmedia/6132a46d-5cfc-4cec-a9da-2ff380179bb1/clinical_guidelines_for_the_management_of_acute_coronary_syndromes_2016.pdf.

- Acute Coronary Syndromes. In: eTG complete (Cardiovascular).Therapeutic Guidelines. Updated March 2018. https://tgldcdp-tg-org-au.elibrary.jcu.edu.au/viewTopic?topicfile=acute-coronary-syndromes.

Link to Queensland Health Suspected Acute Coronary Syndrome Clinical Pathway QH-suspected-acute-coronary-pathway

Read this Summary of the National Heart Foundation’s Clinical Guidelines for the Management of ACS 2016 Summary NHF Clinical Guidelines for the Management of ACS 2016

|

|

Non-adherence with medications prescribed for secondary prevention of ACS can be a real issue for a number of reasons. When a patient is ready to be discharged from hospital, they are given a massive amount of information all at once – follow up GP and specialist appointments, information about their cardiac diagnosis, non-pharmacological advice (including exercises from the physiotherapist and dietary advice from the dietitian) AND very often a BIG bag of NEW medications associated with extensive verbal counselling from the pharmacist and printed CMIs. Sometimes, certain medications are not available at the patient’s community pharmacy and must instead be sourced only through the hospital pharmacy. This can be a significant barrier to adherence, especially for patients who live in rural towns. Read this article for a reminder about the role pharmacists can play in encouraging and facilitating adherence to long-term medications.

COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING

This material has been reproduced and communicated to you by or on behalf of James Cook University in accordance with section 113P of the Copyright Act 1969 (Act).

The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further reproduction or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice.