8.5 Pharmacology of Weight Management

Introduction

Overweight and obesity resembles the presence of excess storage of fat in the body. However, the term overweight is commonly defined as an excess of body weight for height of an individual. Causation of obesity is multifactorial. Increasingly lifestyles, lack of regular exercise, ultra processed food consumption, genetic predisposition, drug-induced, and metabolic disorder as well as socioeconomic and environmental determinants. The “obesogenic environment” is an important concept to understand. Obesogenic environments are the collective physical, economic, policy, social and cultural factors that promote obesity. For example, they may have a high concentration of fast-food outlets and encourage driving over walking, with local shops having processed food and “ready meals” more readily and cheaply available than fresh fruit and vegetables.

In Australia, the socioeconomic and environmental determinants become particularly important in more rural and remote areas and a particularly high burden of obesity in Indigenous communities. In 2017–18, 25% children and adolescents (aged 2–17) and 67% aged 18 and over were overweight or obese in Australia.

Overweight and obesity greatly increases risk of physical, metabolic, and psychological health problems, including cardiovascular disease (CVD), type 2 diabetes, dyslipidaemia, poor mental health and conditions affecting the reproductive and gastrointestinal systems. Chronic obesity is also associated life threatening comorbidities.

Obesity is largely preventable but has become a significant health burden. Most current interventions are focused on the individual level with very limited success. Successful and long-term prevention and management is required to address the obesogenic environments that currently exist.

At an individual level, effective management of overweight and obesity often needs a multidisciplinary approach including lifestyle modification, behavioural and psychological therapy, weight loss pharmacotherapy and bariatric surgery.

Clinical presentation of obesity

In most cases, the presentation of obesity is straightforward, with the patient indicating problems with weight or repeated failure in achieving sustained weight loss. In other cases, however, the patient may present with complications and/or associations of obesity. Patient’s BMI, waist circumference, body fat percentage, comorbidities, previous weight loss attempts and readiness to lose weight are used in the assessment of overweight or obese patients. Many medications including prescribed medicines, over-the-counter medicines, vitamins, herbs, powders (like protein powders), and other supplements may cause weight gain.

| Medicine classes with examples that commonly cause weight gain |

|---|

|

Comorbidities

Patients with comorbidities such as depression and obstructive sleep apnoea may also be obese. The history of comorbidities for any of the following conditions should be recorded.

- Respiratory: Obstructive sleep apnoea, greater predisposition to respiratory infections, increased incidence of bronchial asthma, and obesity hypoventilation syndrome.

- Malignant: Reported association with endometrial (premenopausal), prostate, colon (in men), rectal (in men), breast (postmenopausal), gall bladder, gastric cardia, biliary tract system, pancreatic, ovarian, renal, and possibly lung cancer, as well as with oesophageal adenocarcinoma and multiple myeloma.

- Psychological: Social stigmatization and depression.

- Cardiovascular: Coronary artery disease, essential hypertension, left ventricular hypertrophy, obesity-associated cardiomyopathy, accelerated atherosclerosis, and pulmonary hypertension of obesity.

- Central nervous system (CNS): Stroke, idiopathic intracranial hypertension, and meralgia paresthetica.

- Obstetric and perinatal: Pregnancy-related hypertension, foetal macrosomia, and pelvic dystocia.

- Surgical: Increased surgical risk and postoperative complications, including wound infection, postoperative pneumonia, deep venous thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism.

- Pelvic: Stress incontinence.

- Gastrointestinal (GI): Gallbladder disease (cholecystitis, cholelithiasis), nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), fatty liver infiltration, and reflux esophagitis.

- Orthopaedic: Osteoarthritis, coxa vara, slipped capital femoral epiphyses, Blount disease and Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease, and chronic lumbago.

- Metabolic: Type 2 diabetes mellitus, prediabetes, metabolic syndrome, and dyslipidemia.

- Reproductive: In women: Anovulation, early puberty, infertility, hyperandrogenism, and polycystic ovaries; in men: hypogonadotropic hypogonadism.

- Cutaneous: Intertrigo (bacterial and/or fungal), acanthosis nigricans, hirsutism, and increased risk for cellulitis and carbuncles.

- Extremity: Venous varicosities, lower extremity venous and/or lymphatic oedema.

- Miscellaneous: Reduced mobility and difficulty maintaining personal hygiene.

Management of obesity

A successful management of obesity primarily commences with a comprehensive lifestyle management (i.e., diet, physical activity, behaviour modification), which include the following:

- Self-monitoring of caloric intake and physical activity

- Goal setting – The patient should be well motivated and weight loss goals both for short and long terms should be set and reviewed regularly. For long term goals in specific, it should be patient-centred and individualised.

- Stimulus control – Stimulus control describes situations in which a habit or behaviour is triggered from a specific cue or circumstance e.g., overeating popcorn when the lights go down at the movie theatre.

- Non-food rewards

- Relapse prevention.

Since obesity is considered as a chronic relapsing condition, effective management of obesity should involve a strong partnership between a highly motivated patient with obesity and a team of health professionals including the doctor, pharmacist, dietitian/nutritionist, exercise trainer and a psychologist or psychiatrist. The composition of the team may vary depending on the individual cases with presenting comorbidities. A modest weight loss between 5% and 10% can be achieved through this multidisciplinary team approach.

Non-pharmacological management

Regardless of whether pharmacotherapy is used to assist with weight management, general advice and counselling for lifestyle modification and a lifestyle prescription must be included in the patient’s weight management plan and provided to all patients. For some patients, lifestyle modification alone may be sufficient to achieve weight loss. Evidence suggests that interventions that address nutrition, physical activity and psychological approaches to behavioural change are more effective for weight loss than single interventions.

The following points have been found beneficial for weight management if followed properly:

- having a meal routine

- avoiding processed foods

- walking 10,000 steps (equivalent to 60-90 minutes of moderate activity) each day

- choosing healthy snacks

- choosing healthy drinks (water first and avoid sugary drinks)

- learn how to read food labels when shopping and preparing food

- be aware of portion sizes

- mindful eating techniques

- balanced diet with 5 serves of fruit and vegetables per day

Pharmacological management

Few medications are available for the treatment of obesity. The medications that may be considered for the long-term or short-term treatment of obesity include liraglutide (Saxenda) orlistat (Xenical), phentermine (Duromine) and the fixed-dose combination of bupropion and naltrexone (Contrave).

Generally, the medications approved by the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for obesity are intended for patients with a BMI of 30 or more or of 27 or more with a weight-related risk factor (e.g., diabetes, hypertension). The available medications may be prescribed as an adjunct to lifestyle modification to support weight reduction in specific people, as per the Australian Medicines Handbook.

Pharmacotherapy may also be used to assist with weight maintenance after a VLCD, or to prevent weight gain after a weight loss, regardless of initial method used to lose weight. Response to therapy should be evaluated by week 12. If a patient has not lost at least 5% of baseline body weight, stimulants should be discontinued, as it is unlikely that the patient will achieve and sustain clinically meaningful weight loss with continued treatment.

Glucagonlike peptide-1 agonists (this content has been re-shared from week 6 material)

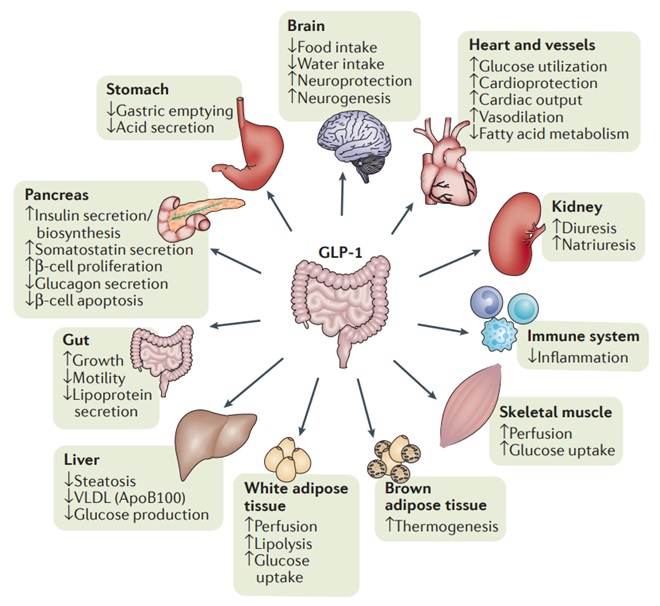

As we already know, GLP-1 has several beneficial effects in T2DM. GLP-1 receptor agonists imitate GLP-1 and bind to GLP-1 receptors (G-protein coupled) producing the physiological effects of endogenous GLP-1 including increased glucose dependent insulin release and delayed gastric emptying.

![GLP-1 Receptor Agonists bind to the G protein coupled GLP-1 receptor which activates cAMP ultimately leading to increased insulin release. Importantly, this requires glucose fuelled ATP formation to close ATP sensitive potassium channels (glucose dependent). Source: Williams J. Pancreapedia. Available online https://pancreapedia.org/molecules/glp-1-version-10 [accessed Aug 2024]](https://jcu.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/81/2024/06/38-GLP1-Insulin.jpg)

In the last few years, GLP-1 RAs have become widely used for both the management of T2DM and for weight loss. There has been a global shortage of GLP-1 RAs due to demand however this appears to be slowly resolving. The following medications in this class are available in Australia (pending supply shortages):

- Semaglutide

- Dulaglutide

- Liraglutide – nonPBS.

Wegovy (semaglutide) and Saxenda (liraglutide) are the TGA approved weight loss formulations of these agents.

GLP-1RAs have shown several benefits compared to DPP-4 inhibitors. They reduce the risk of cardiovascular events, possess some reno-protective properties, produce weight loss (2-5kg) and produce larger HbA1c reductions (almost as good as insulin) – all very positive things for most T2DM patients.

For these reasons, GLP-1 RAs (when stock is available) are preferred to DPP-4 inhibitors. GLP-1RAs sit alongside SGLT-2 inhibitors as the standard add-on therapy to metformin in clinical guidelines.

The primary disadvantage is that currently in Australia, all GLP-1 RAs are only available as subcutaneous injections. This can impact on adherence for some patients and poses other challenges for some patients.

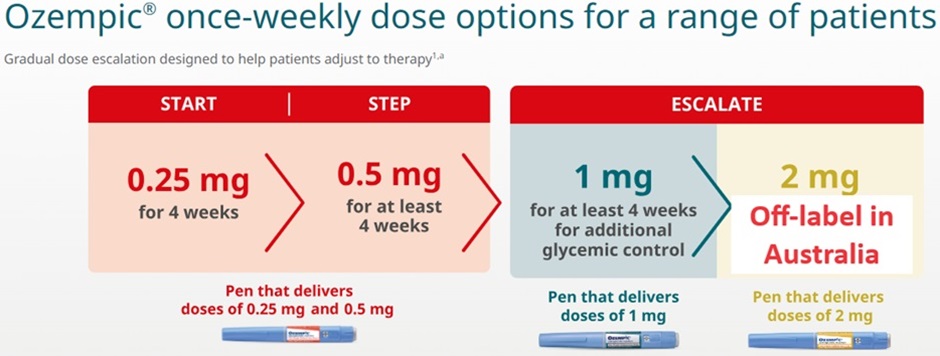

Semaglutide and liraglutide doses are titrated to the target dose over the course of several weeks to minimise gastrointestinal side effects.

Side effects of GLP-1RA

The most prominent side effect with GLP-1 RAs is nausea and gastrointestinal upset likely related to delayed gastric emptying. This can be severe and lead patients to discontinue treatment.

Clinical trials using semaglutide showed an increased risk of retinopathy complications. Patients with retinopathy should be closely monitored if commenced on GLP-1 RAs.

Most patients will also experience a small increase in heart rate of 2-3 beats per minute but this does not appear clinically significant. Other side effects are broadly similar to DPP4 inhibitors including precautions relating to pancreatitis.

GLP-1RAs cause a significant reduction in gastric emptying. There is emerging evidence that this can increase the risk of aspiration during surgery if patients are not adequately fasted prior to general anaesthesia.

Orlistat

Orlistat blocks the action of pancreatic lipase, reducing triglyceride digestion and preventing absorption of approximately 30% of dietary fat. Two major clinical trials showed sustained weight loss of 9-10% over 2 years. In Australia, orlistat is approved as an adjunct to lifestyle modification in obesity (BMI ≥ 30) or in overweight people (BMI ≥ 27) with other cardiovascular risk factors. The drug may reduce absorption of some fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K) and beta-carotene, as well as absorption of some medications.

Adverse effects include flatulence, fatty/oily stool, increased defecation, and faecal incontinence. The use of orlistat for overweight and obesity is part of standard pharmacist care and practice; guidance on its use is not covered in detail in this module. Patients should be referred to the Pharmaceutical Society of Australia’s Guidance for provision of a Pharmacist Only medicine Orlistat and Australian Medicines Handbook: Orlistat for further information, including dosage recommendations, contraindications and precautions, adverse effects and drug interactions.

Phentermine

Phentermine is a sympathomimetic agent and produces CNS stimulatory effects, increasing energy expenditure. In Australia, it is indicated for short-term use only as an adjunct to lifestyle modification in obese adults with BMI ≥ 30 or over 25 with other cardiovascular risk factors.

The common adverse effects of phentermine include overstimulation of the CNS (eg insomnia, restlessness, nervousness, agitation), arrhythmia, tachycardia, hypertension, diarrhoea, vomiting, headache, rash, urinary frequency, facial oedema, unpleasant taste, urticaria and impotence.

Bupropion and naltrexone

The combination of bupropion and naltrexone is approved in Australia for the weight management in adults with BMI ≥ 30 or ≥ 27 with other cardiovascular risk factors. This combination is thought to cause a reduction in appetite and increase in energy expenditure by increasing the activity of pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) neurons.

Bupropion increases dopamine activity in the brain, which appears to lead to a reduction in appetite and increase in energy expenditure by increasing activity of POMC neurons. Naltrexone blocks opioid receptors on the POMC neurons, preventing feedback inhibition of these neurons and further increasing POMC activity.

Medications used off-label

Several medications that are approved for other indications but that may also promote weight loss have been used off-label for obesity. These include several antidepressants, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Medications used off-label for obesity include the following:

- Methylphenidate – Not approved by the FDA for obesity management, but several anecdotal reports have described it as having variable success for this purpose.

- Zonisamide – Gadde and colleagues reported that randomized use of the antiepileptic drug zonisamide in a cohort of 60 obese subjects was associated with a weight loss of about 6% of baseline weight, with few adverse effects.

- Octreotide – Lustig and colleagues reported the potential utility of octreotide in ameliorating the distinct subclass of hypothalamic obesity.

- The other medications used as off label in weight management include medications for diabetes, cannabinoid receptor antagonists and neuropeptide YY antagonists.

📺 Watch the following lecture on the management of overweight and obesity (19 minutes)

Lecture Notes

Lecture Notes

COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING

This material has been reproduced and communicated to you by or on behalf of James Cook University in accordance with section 113P of the Copyright Act 1969 (Act).

The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further reproduction or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice.