Palliative and End-of-Life Care

Tracey Gooding and Sandra Dash

Learning Outcomes

In this chapter, you will learn how to:

- Define palliative and end-of-life care

- Identify the role of a nurse in palliative and end-of-life care

- Apply Kübler-Ross’s five stages of grief model to assess the different stages of grief in patients and families during palliative and end-of-life care

- Identify common symptoms and needs experienced by patients nearing the end of life

- Demonstrate appropriate communication strategies when engaging with patients and families at the end of life

- Develop a holistic care plan to support dying patients and their families

- Analyse the impact of cultural values, beliefs, and practices on patients’ and families’ experiences of dying and bereavement.

Introduction

As nurses, we are privileged to care for individuals and their families during the most vulnerable and profound moments of life, including the end of life. During this time, clinical expertise must be matched with deep compassion and emotional presence. This role goes beyond the mere alleviation of physical symptoms; it encompasses upholding dignity, the provision of comfort, and the facilitation of psychosocial and spiritual support when curative interventions are no longer viable.

This chapter introduces the foundational principles and evidence-informed practices essential to high-quality end-of-life care. It underscores the importance of holistic, person-centred nursing approaches that are responsive to the individual’s values, cultural identity, and expressed wishes. Regardless of their specialty or level of experience, nurses inevitably face situations involving death and dying, whether it be from terminal illnesses, expected outcomes, or unforeseen events. Additionally, nurses frequently play a crucial role in supporting individuals dealing with acute or chronic grief. It is essential for nurses to possess emotional awareness and emotional intelligence when tending to patients undergoing the dying process, those expecting impending loss, and those going through the grieving process. Nurses must be equipped to navigate intricate discussions, remain composed, and effectively address emotions such as anger, guilt, sadness, and fear. No matter what area of nursing you work in, this chapter will enhance your capacity to identify and address the multifaceted needs of dying individuals, support families, and integrate culturally safe and inclusive care strategies while maintaining personal resilience in clinical practice.

Defining Palliative and End-of-Life Care

According to the World Health Organization (WHO, 2020), palliative care is “an approach that improves the quality of life of patients (adults and children) and their families who are facing problems associated with life-threatening illness. It prevents and relieves suffering through the early identification, correct assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, whether physical, psychosocial or spiritual” (para. 1). Palliative Care Australia (PCA) defines palliative care as “person and family-centred care provided for a person with an active, progressive, advanced disease, who has little or no prospect of cure and who is expected to die, and for whom the primary treatment goal is to optimise the quality of life” (PCA, 2018, p. 6). Palliative care can be conducted in any clinical environment, with some healthcare institutions having a dedicated palliative care unit. This care can be utilised several months to some years before end-of-life is expected.

End-of-life care is a type of palliative care and is defined by the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare as “the period when a person is living with, and impaired by, a fatal condition, even if the trajectory is ambiguous or unknown” (ACSQHC, 2023, p. 27). There is no real consensus on when the period of time known as the end-of-life begins and this is because end-of-life differs depending on the illness that a person is suffering. However, according to ACSQHC (2023, p. 27), people are considered to be “approaching end-of-life” when they are likely to die within the next 12 months. The goal of end-of-life care is the same as palliative care – to deliver care in line with the physical, spiritual and psychosocial needs of the patients, families and carers, but also includes the care of the patient’s body after their death (ACSQHC, 2023).

In the past, palliative care has typically been seen as something that began only after all curative treatments had ended. Today, it is widely understood that palliative care can be beneficial when provided alongside treatments that aim to slow disease progression and extend life. It is also now recognised that many people with life-limiting conditions are not cured, but instead live with these illnesses for many years (PCA, 2018). According to Palliative Care Australia, palliative care should be everyone’s business, and all healthcare professionals involved in supporting people with life-limiting illnesses, as well as their families and carers, should possess core competencies and skills in delivering palliative and end-of-life care (PCA, 2018).

Palliative and End-of-Life Care in Australia

According to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW, 2025), there were 101,000 palliative care-related hospitalisations in 2022-23. The average age at admission was 75 years. Almost 3 in 5 (57%) ended with the patient dying in hospital. Between 2015-16 and 2022-23, there was a 37% increase in the number of palliative care-related hospitalisations, suggesting that the ageing of Australia’s population is contributing to the growth in palliative care-related hospitalisations (AIHW, 2025). This does not include palliative or end-of-life care delivered in the home, residential care facilities or as an outpatient.

Each year, many Australians access care through outpatient services provided in non-admitted settings, including hospital outpatient departments, community clinics, and even in their own homes. These services are often connected to a previous emergency visit or hospital admission and are used to deliver diagnostic assessments or follow-up care without the need for the person to be admitted to hospital again. In 2022-23, there were 882,000 palliative care-related service events where the patient was not admitted to hospital (AIHW, 2025). This highlights the substantial role of outpatient and community-based palliative care and reflects a trend toward delivering palliative care in more flexible, patient-centred environments, such as homes and clinics, which may better support quality of life and personal preferences at the end of life. Despite this increase, access to specialist palliative care in the community remains uneven and often inadequate, particularly in rural and regional areas. Palliative Care Australia (PCA) has highlighted that while specialist services are expected to include a broad range of allied health professionals, many community settings lack the infrastructure and workforce to deliver comprehensive care (PCA, 2022). Addressing these gaps is essential to ensure equitable access to quality end-of-life care across Australia.

National Palliative Care Standards

The Australian National Palliative Care Standards, developed by Palliative Care Australia, provide a framework for delivering high-quality, person-centred care to individuals with life-limiting illnesses, as well as their families and carers. There are two resources available: National Palliative Care Standards for All Health Professionals and Aged Care Services (PCA, 2022) and National Palliative Care Standards for Specialist Palliative Care Providers (PCA, 2024). Both are guided by the following nine national standards:

These standards guide healthcare professionals across all settings, from specialist services to aged care, community and general practice, ensuring that care is respectful, responsive, and aligned with the values and needs of those receiving it. The standards emphasise holistic assessment, collaborative care planning, support for carers, and continuous quality improvement, promoting dignity and comfort at end-of-life. The published standards (linked below) also address diversity within each standard, offering guidance on providing care for people with a wide range of needs. This includes children; Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples; individuals experiencing mental illness, substance use disorders, dementia, disability, or homelessness; and those in aged care, prison custody, culturally and linguistically diverse communities, or who identify as LGBTQIA+.

Link to Learning

The ACSQHC also provides guidelines for caring for people at the end-of-life. The Comprehensive Care Standard within the National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards (ACSQHC, 2021) has a specific section related to providing comprehensive care at the end-of-life. This section outlines strategies and specific actions for providing comprehensive, holistic, patient-centred, goal-directed, compassionate care to palliative care patients. The actions specific to comprehensive care at the end-of-life include (ACSQHC, 2021):

Action 5.15 – The health service organisation has processes to identify patients who are at the end-of-life that are consistent with the National Consensus Statement: Essential Elements for Safe and High-Quality End-of-Life Care.

Action 5.16 – The health service organisation providing end-of-life care has processes to provide clinicians with access to specialist palliative care advice.

Action 5.17 – The health service organisation has processes to ensure that current advance care plans can be received from patients and are documented in the patient’s healthcare record.

Action 5.18 – The health service organisation provides access to supervision and support for the workforce providing end-of-life care.

Action 5.19 – The health service organisation has processes for routinely reviewing the safety and quality of end-of-life care that is provided against the planned goals of care.

Action 5.20 – Clinicians support patients, carers and families to make shared decisions about end-of-life care in accordance with the National Consensus Statement: Essential Elements for Safe and High-Quality End-of-Life Care.

The National Consensus Statement: Essential Elements for Safe and High-Quality End-of-Life Care, developed by the ACSQHC (2023), outlines the foundational elements required to deliver safe, high-quality, and person-centred care at the end of life. It provides a nationally agreed framework to guide health services, clinicians, and policymakers in improving care experiences for individuals, families, and carers. The statement is a key reference for embedding best practice into clinical and governance systems across Australia. It outlines nine guiding principles and ten essential elements that support person-centred, culturally responsive, and clinically safe care across all settings, including hospitals, hospices, residential aged care, and home environments (ACSQHC, 2023). If you would like to explore these principles in more detail, you can scroll through the full document below.

When reading the National Consensus Statement: Essential Elements for Safe and High-Quality End-of-Life Care (ACSQHC, 2023) and the National Palliative Care Standards (PCA, 2022), you may have noticed that both documents share a number of overlapping themes. Both address the principles of care delivery and the structures that support clinical governance in end-of-life care. The following infographics present these two perspectives side by side: one focused on the principles of care delivery, and the other on the governance structures that make such care possible. Together, they offer a comprehensive view of what safe, effective and quality end-of-life care should look like. Click or press on the dots beside each principle to reveal more information and explore its meaning in the context of end-of-life care.

Palliative and End-of-Life Care Needs for Diverse Populations

Palliative and end-of-life care in Australia encompasses a broad spectrum of individuals, ensuring that palliative care caters for the diverse needs of the population. What does diversity mean in care contexts? Diverse populations include individuals who belong to one or more groups that may have faced exclusion, discrimination, or stigma. Some common types of diversity include (Department of Health, 2017; Palliative Care Australia, 2022):

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples

- People with culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) backgrounds

- Lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and gender diverse, and intersex (LGBTI) people

- People who are homeless or at risk of homelessness

- People of different ages, including paediatric and geriatric populations

- People who live in rural or remote areas

- People living with mental illness

- People living with cognitive impairment, including dementia

- People with disability

- People with different religious and spiritual beliefs

- People with socio or economic disadvantage

- People living with addictions or substance abuse disorders

- People who live in prison custody.

While people within these groups may share some common experiences, it is important to recognise that each person has unique preferences and needs. These can relate to their social, cultural, linguistic, religious, spiritual, psychological, medical, and care circumstances. Providing respectful and inclusive care means understanding and responding to these individual differences and not making assumptions based on group identity (Department of Health, 2017).

To ensure safe, high-quality care for people from diverse backgrounds, several national and state guidelines and standards have been developed to help tailor care to the specific needs of different communities. While this chapter cannot cover every diverse population in detail, it is your responsibility as a nurse or future nurse, to actively seek out education and resources relevant to the communities you may serve. The following section offers a starting point to understanding some of the diverse needs in the Australian community and some of the current guidelines for Australian clinicians to deliver care that is respectful, evidence-based, and aligned with the individual preferences and needs of diverse patients and their families.

Palliative and End-of-Life Care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples

Providing end-of-life care for First Nations people requires a culturally safe, respectful, and person-centred approach that honours the values, beliefs, and traditions of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. Health professionals must recognise the significance of kinship systems, which often extend beyond immediate family, and ensure that care decisions involve the appropriate family members as identified by the person receiving care. Communication should be mindful of both verbal and non-verbal styles, avoiding medical jargon and using culturally appropriate language, such as “finishing up” or “passed on”, in place of direct references to death (IPEPA Project Team, 2020). Many First Nations individuals may wish to spend their final days on Country, making it essential to support this preference where possible (caring@home, 2022). Respecting Sorry Business practices, which may include traditional ceremonies and extended grieving periods, is vital for supporting families and communities. Building trust through genuine relationships, acknowledging spiritual beliefs, and empowering autonomy in decision-making are all central to delivering compassionate and culturally responsive palliative care (IPEPA Project Team, 2020; Queensland Health, 2015).

Sad News, Sorry Business: Guidelines for Caring for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People Through Death and Dying is a culturally responsive framework developed by Queensland Health to support health professionals in providing respectful and safe end-of-life care. These guidelines recognise the sacred and sensitive nature of death and bereavement within Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, where Sorry Business encompasses mourning practices, ceremonies, and collective grieving. The document emphasises cultural capability, respectful communication, relationship-building, and trauma-informed care, particularly in cases of sudden or unexpected death. It provides practical guidance for nurses and other healthcare workers to honour cultural protocols, support families, and uphold dignity during the final stages of life and after death (Queensland Health, 2015). To deepen your understanding of culturally safe and respectful end-of-life care for First Nations peoples, you can access the full document below. It offers valuable insights into traditions, beliefs, and practices that shape how death and dying are experienced within Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. Read through the document below to gain a better understanding of supporting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples through the death and dying process.

Cultural Considerations: Providing End-of-Life Care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples is another resource developed by the IPEPA Project Team (2020), which offers culturally grounded guidance for health professionals delivering palliative care to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Informed by extensive community consultation across urban, rural, and remote regions, the guide supports culturally safe, person- and family-centred care. It highlights the importance of Indigenous knowledges, kinship structures, and holistic practices, and aims to build the capacity of both Indigenous and non-Indigenous healthcare workers to provide respectful, responsive care at the end-of-life (IPEPA Project Team, 2020).

Link to Learning

In many First Nations communities, the end-of-life is not only a personal journey but a deeply cultural one. The following document offers practical guidance for First Nations health professionals supporting families through palliative care at home. It acknowledges the importance of place, kinship, and cultural practices in shaping how care is delivered and received when someone chooses to spend their final days on Country (caring@home, 2022).

Link to Learning

Paediatric Palliative and End-of-Life Care

The National Consensus Statement: Essential Elements for Safe and High-Quality Paediatric End-of-Life Care outlines the core principles and practices required to deliver compassionate, developmentally appropriate care to children nearing the end of life. Developed by the ACSQHC, this statement builds upon the adult framework but recognises the unique clinical, emotional, and ethical considerations involved in paediatric care. It emphasises the importance of family-centred approaches, clear communication, and multidisciplinary collaboration to support both the child and their caregivers. The statement serves as a foundational guide for nurses and other health professionals working in acute, community, and hospice settings to ensure that paediatric patients receive care that is safe, respectful, and aligned with their needs and values (ACSQHC, 2016).

Perinatal Palliative and End-of-Life Care

Perinatal palliative care is a model of care that is holistic and multidisciplinary and aims to provide end-of-life care and optimal symptom control for a baby, along with specialised support for families from diagnosis through to bereavement (Palliative Care Australia, Pediatric Palliative Care Australia, and New Zealand, 2022). The national Care Around Stillbirth and Neonatal Death (CASaND) Clinical Practice Guideline (Stillbirth Centre of Research Excellence, 2024) acknowledges that perinatal palliative care is a right for all babies who have a life-limiting or life-threatening condition. Care should be initiated from diagnosis, whether that be during pregnancy or after birth, as recognised in the national Stillbirth Clinical Care Standard (ACSQHC, 2022).

Perinatal mortality can occur after birth-related trauma or in relation to congenital anomalies. Congenital anomalies are a major cause of perinatal death in Australia (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2024). A congenital anomaly is a difference in the genetics, development or health of a baby, present at birth. Some anomalies are associated with fetal, newborn or childhood death and are considered life-limiting, such as trisomy 18 or trisomy 13. Some anomalies may be treated with life-sustaining surgery and are considered life-threatening, such as congenital heart anomalies. Although perinatal palliative care is acknowledged as vital for babies and families with a life-limiting or life-threatening condition, there is also a call to integrate perinatal palliative care into care for all babies with an uncertain prognosis (Wilkinson et al., 2025).

As antenatal screening technologies continue to advance, more fetal anomalies are being identified during pregnancy. However, access to perinatal palliative care during the antenatal period remains limited, and parents in Australia who continued pregnancy after a life-limiting fetal diagnosis described their care as ‘ad hoc’ (Weeks, 2020). End-of-life care during the neonatal period, particularly within neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) and special care nurseries, is more widely recognised, and health services and clinical excellence agencies have dedicated clinical guidance to support best practice, such as the Palliative (end of life) neonatal care best practice guidance by Safer Care Victoria.

Perinatal palliative care teams work within state-based paediatric palliative care teams around Australia, which can be located through Palliative Care Australia’s National Service Directory. Such teams can provide care coordination, outreach or secondary consultation. However, all health professionals can provide care that builds upon the key elements of perinatal palliative care.

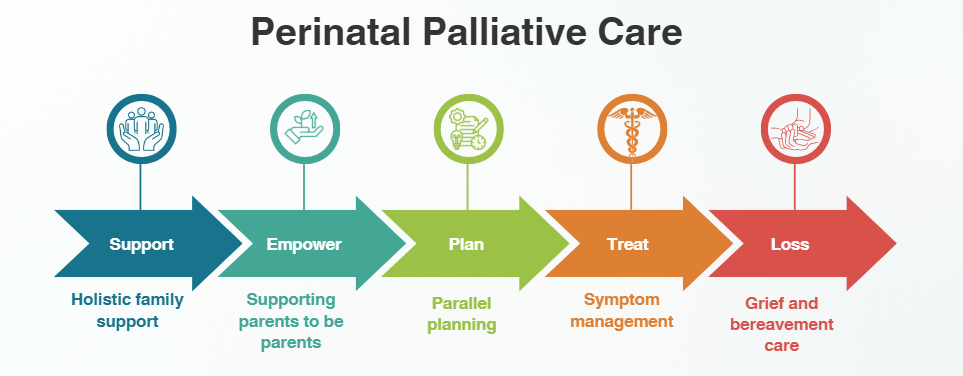

Wilkinson et al. (2025) described five elements of perinatal palliative care:

Palliative and End-of-Life Care for the LGBTQIA+ Community

Palliative and end-of-life care for LGBTQIA+ individuals must be inclusive, affirming, and free from discrimination. Many LGBTQIA+ people have experienced lifelong stigma, marginalisation, and trauma, which can shape how they engage with healthcare services—particularly at vulnerable times such as the end of life. Inclusive care involves recognising diverse identities, respecting chosen families, and avoiding assumptions about gender, sexuality, or relationships. Health professionals should create welcoming environments by using inclusive language, acknowledging pronouns, and ensuring that care plans reflect the individual’s values and support networks.

Resources like the LGBTIQ+ Inclusive Palliative Care Toolkit (Palliative Care ACT, 2022) and ELDAC’s inclusive end-of-life care guide for aged care providers (ELDAC, 2022) offer practical strategies for embedding inclusivity into clinical practice, including how to navigate advance care planning, spiritual care, and bereavement support at end of life. You can access these helpful resources below for more information.

Links to Learning

Palliative and End-of-Life Care for People from CALD Backgrounds

People from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) backgrounds often face distinct challenges when accessing palliative care services. A recent review to identify cultural considerations for people from CALD backgrounds at the end-of-life in Australia identified four themes: communication and health literacy; access to end-of-life care services; cultural norms, traditions and rituals; and the cultural competence of healthcare workers (Lambert et al., 2023). Language barriers can make it difficult to communicate symptoms, understand care options, or participate in advance care planning. Access to translation services is integral in these circumstances. Additionally, cultural beliefs and values around caregiving, gender roles, privacy, and authority may shape how care is received and lead to hesitation in accessing services. Having an understanding of different cultures and the barriers and enablers for this population to palliative care services can help nurses respond appropriately to cultural diversity and improve the quality of palliative and end-of-life care. To learn more about the CALD population in Australia and how palliative care standards can be improved, access the links below.

The Role of the Nurse in Palliative and End-of-Life Care

- Communication skills, especially when conveying potentially distressing information regarding prognosis and care options for people close to death

- Effective management of symptoms, including pain

- Critical appraisal skills, including the ability to assess a person’s palliative care requirements, whether medical, functional, psychological, financial, emotional or spiritual

- Skills in providing advice and assisting with advance care planning

- Ethical decision making

- Life closure skills related to care provided when people are close to death that aim to preserve the dignity of the person and their family. (PCA, 2018, p. 29)

This section explores how nurses can support patients and their families during this time, guided by the first six National Palliative Care Standards (PCA, 2022), which describe the systems, processes and enablers necessary to deliver high-quality palliative care. These 6 standards focus on comprehensive assessment of needs, developing the comprehensive care plan, caring for carers, providing care, transitions within and between services and grief support (PCA, 2022).

Comprehensive Assessment of Needs

Comprehensive assessment of needs refers to the initial and ongoing assessment that incorporates the person’s physical, psychological, cultural, social, and spiritual experiences and needs (PCA, 2022, p. 18). Recognising when a person is approaching end-of-life is the first step in ensuring comprehensive assessment of needs. Ask yourself, “Would you be surprised if this person died within the next 12 months”? If the answer is yes, this may be a trigger to initiate and provide quality end-of-life care (ACSQHC, 2023). There are many assessment tools used to help identify persons with palliative care needs and enable improved assessment, symptom management and support. For example, the AMBER Care Bundle, Supportive and Palliative Care Indicators Tool (SPICT), and the Palliative Care Outcomes Collaboration (PCOC) assessment form.

The AMBER Care Bundle is designed for patients who are clinically unstable and whose recovery is uncertain. It supports multidisciplinary teams in identifying such patients early and initiating timely conversations about care preferences, escalation plans, and goals of care. The bundle includes structured interventions and timelines to ensure that critical decisions—such as resuscitation status and escalation to intensive care—are addressed proactively. It also emphasises the importance of sensitive communication with patients and families, tailored to their pace and capacity for understanding. To learn more about the AMBER care bundle, you can access the website below.

Link to Learning

Follow the link to access more information about the AMBER Care Bundle from the Clinical Excellence Commission.

The SPICT tool helps clinicians identify people at risk of deteriorating and dying due to one or more advanced conditions. It uses clinical indicators and prompts to support early recognition and referral to appropriate services. SPICT is particularly useful in generalist settings where specialist palliative care may not be immediately available. The SPICT-4ALL tool is a plain language version of the SPICT, making it easier for everyone to talk about deteriorating health and ask about more help and support. To learn more about the SPICT tool, you can access the website below.

Link to Learning

Follow the link to access The SPICT tool.

Follow the link to access the SPICT-4ALL tool.

The PCOC is funded by the Australian Government and provides assessment tools to facilitate routine palliative assessment and clinical response. The form assesses levels of delirium, pain and other common symptoms in palliative patients and their ability to complete activities of daily living (ADLs). To learn more about the PCOC, you can access the website below.

Link to Learning

Follow the link to access the Palliative Care Outcomes Collaboration (PCOC).

This comprehensive assessment provides the foundation for developing the comprehensive care plan.

Developing the Comprehensive Care Plan

At this stage, the patient, their family and carers, and substitute decision-maker(s) work in partnership with multidisciplinary teams to communicate, plan, set goals of care and support informed decisions about the care plan. All too often, patients and families leave decision-making too late, which can see the family solely being responsible for decisions that they are not sure about. In turn, not having decisions made early causes a loss of valuable time for both the patient and their family (Welsch & Gottschling, 2021).

Ensuring Inclusivity and Responsiveness in Care Planning

A comprehensive care plan is essential for delivering safe, person-centred palliative care that respects the individual’s values, goals, and preferences. Individuals should be actively involved in planning their care, and, where consistent with their wishes, family members and carers should also be included in the process (ACSQHC, 2023; PCA, 2022). In cases where the person is unable to participate due to age, cognitive impairment, or incapacity, a legally appointed substitute decision-maker or guardian should be identified in accordance with relevant legislation and the person’s known preferences (PCA, 2022). Recognising the uniqueness of each person and the potential for care goals to evolve over time is vital to ensuring the care plan is flexible and inclusive, taking into account cultural identity, gender, sexuality, and other aspects of diversity. Additional support may be required for vulnerable populations, such as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, including referrals to social work or guardianship services (ACSQHC, 2023; PCA, 2022). Development and communication of the plan may also require the use of interpreters for people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds, and assistive communication tools for those with sensory or cognitive impairments (ACSQHC, 2023). This care plan should be updated with each reassessment of the patient to ensure it remains responsive to their evolving needs, and clearly documented in the clinical record, including any decisions made and any unresolved issues requiring follow-up.

Advance Care Planning

Advance Care Planning (ACP) is a dynamic and person-centred process that involves both discussion and documentation of an individual’s values, beliefs, and preferences for future health and personal care. It typically includes conversations about the person’s understanding of their illness, concerns about their health and care, goals and priorities, preferred place of care, and the identification of substitute decision-makers. Terminology and legal recognition of ACP documents may vary across states, but commonly used components include the following: (Flip the cards to understand the terminology used in advanced care planning discussions)

Individuals should be supported to document their future care preferences through advance care directives or Goals of Care documents, which should be accessible to all healthcare providers (ACSQHC, 2023; PCA, 2022). Advance care planning should be introduced early, with clear information provided about its purpose and process. Individuals should be offered the opportunity to initiate or revise an advance care directive, and, where appropriate, family members, carers, and substitute decision-makers should be involved in these discussions. Legally binding directives should be promoted where possible, and individuals should be encouraged to upload these documents to My Health Record to ensure they are readily available across care settings (PCA, 2022).

Research has shown that there needs to be much improvement in ACP invitation and completion rates in Australia, particularly in the area of patients with advanced cancer (Veltre et al., 2023). ACP is supported by national standards across aged care, general practice, and healthcare services, and can be facilitated by both registered and non-registered health practitioners. Importantly, individuals may also choose to engage in ACP with family members or trusted others, outside of formal healthcare settings. These discussions can be started early and should be integrated into the assessment and development of a comprehensive care plan to ensure ACP is meaningful and actionable.

Adapting the Care Plan for End-of-Life Transitions

Timely recognition of a person’s transition to the terminal phase of life is critical to ensuring timely adaptation of the care plan and that the patient’s wishes at end-of-life are carried out. When this occurs, it is important to communicate this change in plan to the patient, their substitute decision-maker, family, carers, and other healthcare providers involved in their care. The care plan should be revised to reflect the unique needs of all involved during this phase, including confirming the preferred place of care and ensuring appropriate supports, such as pastoral care and home care needs, are in place (ACSQHC, 2023; PCA, 2022).

Caring for the Carers

According to the most recent Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Survey of Disability, Ageing and Carers, approximately 3 million Australians, or 11.9% of the population, were providing informal care in 2022 (ABS, 2022). An evaluation of the needs and preferences of an individual’s family members, carers, and substitute decision-makers is essential to ensure they receive tailored support and clear, practical guidance. This process plays a critical role in shaping how their contributions are understood, acknowledged, and supported within the care framework (PCA, 2022, p. 22). Families and carers often assume substantial responsibilities when supporting individuals with life-limiting illnesses. This informal or unpaid care can encompass a broad spectrum of tasks, including personal care (such as assistance with showering), nursing duties (like symptom management and medication administration), household chores (e.g., cooking and cleaning), financial support (particularly when income is impacted), practical assistance (such as transportation), emotional support, and active involvement in planning and coordinating care and services (PCA, 2018).

Assessing the Needs of Carers

Clinicians should work collaboratively with carers and families to understand their desired level of involvement and discuss the potential benefits and risks of assisting with care. Ongoing assessment of carers’ willingness and ability to participate is essential, as is providing up-to-date information and resources tailored to their needs, including education about how to safely assist with care, such as medication management, risk reduction, manual handling, and activities of daily living, and education and resources for emotional support (PCA, 2022). Additionally, carers should receive information about the signs and symptoms of approaching death and guidance on what steps to take following death, delivered in a manner appropriate to their age, culture, religion, and social situation (ACSQHC, 2023; PCA, 2022). It is important to recognise that family situations may be complex, and not all carers will be family members; some may be friends or members of the community (PCA, 2022).

Recognising Diversity

It is essential to acknowledge the diversity among carers. Young carers, LGBTIQ+ partners, and carers from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds may face unique challenges and burdens. In Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander contexts, family and kinship structures may require the involvement of multiple decision-makers, and additional support may be needed to address fragmented family connections due to colonisation (PCA, 2022).

Supporting the Wellbeing of Carers

Supporting the wellbeing of carers is a fundamental aspect of high-quality palliative care. This includes providing emotional support, opportunities for peer connection, and access to professional counselling or debriefing when needed. Healthcare providers should ensure carers are aware of available supports and encourage them to seek help for feelings of distress or burnout (ACSQHC, 2023; PCA, 2022). Support for carers can also include access to respite care, community resources, therapy to develop coping mechanisms for processing caregiver burnout and grief support services before and after the death of their loved one. In the context of palliative care, respite care is an important factor to consider when caring for the carers as it offers short-term or occasional relief, allowing them temporary breaks from their ongoing responsibilities. This support is vital for maintaining the carer’s wellbeing and sustaining their ability to continue in their role effectively (PCA, 2018). Caregiver burnout and compassion fatigue are similar concepts that explain the emotional toll experienced by individuals caring for others. Both caregiver burnout and compassion fatigue may result in emotional and physical symptoms, signalling a state of stress and extreme exhaustion. Nurses can anticipate possible caregiver fatigue and proactively prepare the caregiver and encourage the use of available respite services before burnout occurs.

Providing Care

Care is guided by a thorough assessment of the individual’s needs, is grounded in evidence-based practice, and aligns with the person’s documented values, goals, and preferences as outlined in their care plan (PCA, 2022). This approach ensures timely responses to needs, ongoing evaluation of treatment effectiveness, and continuous access to palliative care for the individual, their family, carers, and substitute decision-makers. Additionally, any distress, whether physical, psychosocial, cultural, spiritual, or related to social determinants of health, is proactively anticipated and addressed promptly and effectively when it arises (PCA, 2022, p. 25).

Comfort Care Measures

The nurse’s role includes the knowledge and skills to maximise the patient’s comfort level to their desired outcome. The nurse must think about comfort holistically to include not only physical and psychological comfort, but spiritual and social comfort as well.

The only way to ensure adequate comfort in all these areas is to talk with the patient. The nurse must get to know the patient and establish a good nurse-patient relationship. A nurse can learn a lot about what is important to their patient by simply asking them. Comfort care measures provide pain control, relief from anxiety and agitation, support from spiritual leaders, and assistance with bodily functions and activities of daily living. Table 1 lists comfort care interventions for common end-of-life situations (National Institute on Aging, 2022).

| End-of-Life Situation | Nursing Interventions |

| Pain |

|

| Breathing problems |

|

| Skin irritation |

|

| Digestive problems |

|

| Temperature sensitivity |

|

| Fatigue |

|

| Emotional disturbance |

|

Management of Pain

Pain is one of the most common symptoms in palliative care and perhaps one of the greatest concerns of patients who are nearing the end of life. In Australia, pain relief medications accounted for 8 in 10 (79%) of palliative care-related prescriptions in the period 2023-24, highlighting the central role of pain management for palliative care patients (AIHW, 2025). Although pain is one of the most frequently encountered symptoms in palliative care, it remains inadequately managed in many cases. Any pain management in palliative care should start with a thorough pain assessment followed by the formation of a pain management plan and continuous re-assessment to ensure that the method of pain relief is effective and to minimise and address any side-effects (Franklin & Lovell, 2024). Pain is a symptom that requires continual assessment and evaluation of the current interventions used for its management. As those who work with patients in pain know, the longer pain is left unmanaged, the more difficult it may be to treat. Effective management requires routine screening, thorough assessment when pain is identified, and the implementation of appropriate interventions. These may include localised and systemic treatments, as well as both pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions (Franklin & Lovell, 2024).

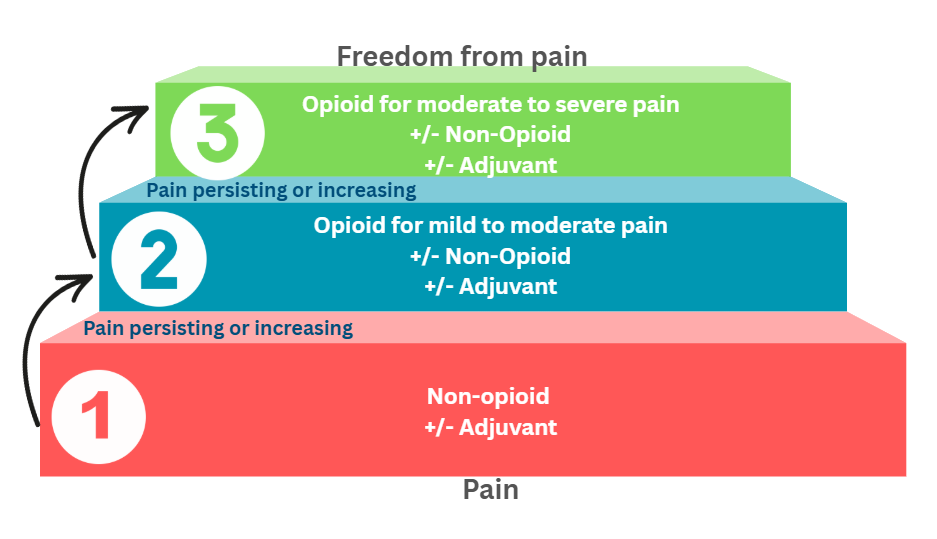

Pharmacological Interventions

The World Health Organization (WHO, 2018) recognises that pain in terminal illness cannot always be completely eliminated. The goal of pain management, therefore, is to alleviate discomfort to a degree that enables the patient to maintain a level of quality of life that they personally find acceptable. The World Health Organization developed a three-step ladder for cancer pain in adults and adolescents, which can be used as a general guide to pain management and could be transferable to any pain during terminal illness. The World Health Organization’s approach to pain management in cancer pain is guided by four key principles: By the clock, by the mouth and by the ladder.

By the Clock

To effectively manage pain, medications should be administered at consistent intervals rather than only when symptoms arise. This scheduled dosing helps maintain continuous relief and is tailored to the type of medication, whether it’s short-acting or long-acting. The dose should be increased until the patient is comfortable and the next dose given before the effect of the previous dose has worn off (WHO, 2018).

By Mouth

Oral administration is generally favoured due to its simplicity and suitability across various care environments. However, when oral intake is not possible, such as in cases of unconsciousness or swallowing difficulties, alternative routes should be considered. Less invasive methods like sublingual or subcutaneous delivery are preferred over intravenous options, and intramuscular injections are discouraged due to discomfort and variability in absorption (WHO, 2018).

With Attention to Detail

The first and last doses of the day should be linked to the patient’s waking time and bedtime. Ideally, the patient’s analgesic medicine regimen should be written out in full for patients and their families to work from and should include the names of the medicines, reasons for use, dosage and dosing intervals. Patients should be warned about the possible adverse effects of each of the medicines they are being given.

For the Individual

Management of an individual patient’s pain requires careful assessment, plus differential diagnosis of the type of pain, the site of origin of the pain and a decision about optimum treatment. The correct dose is the dose that relieves the patient’s pain to a level acceptable to the patient. While pain assessment tools like the three-step ladder below (Figure 3) can offer valuable insights into managing pain and can be useful as a teaching tool, they are not universally applicable to every patient. Pain management should always be individualised and informed by a comprehensive clinical evaluation. This includes considering the patient’s overall health status, existing medical conditions, cardiovascular stability, potential side effects of treatment, the urgency of their condition, and both past and current therapeutic interventions (WHO, 2018).

Pain relief should follow a structured progression based on severity. However, note that in cases of severe pain, it may be appropriate to start directly with a strong opioid. The first step of the ladder includes non-opioid medications (e.g. Paracetamol or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs]), plus an adjuvant medication if appropriate. If pain persists, the next step on the ladder for increasing mild to moderate pain is mild opioid medications (e.g. codeine), plus a non-opioid and/or adjuvant medication if applicable. If pain persists, the third and final step on the WHO ladder is the use of strong opioid medications (e.g., morphine or hydromorphone), also with or without the non-opioid and/or adjuvant medication if applicable. Once effective pain control is achieved, the patient should remain on the dose that works, unless the underlying cause of pain resolves (WHO, 2018). See Figure 3 for a visual representation of the 3-step analgesic ladder.

A wide range of pharmacological options are available to support effective pain relief in palliative care. These interventions are selected based on the nature and severity of the pain, the patient’s overall condition, and their response to previous treatments. Understanding the different classes of medications and their roles is essential for tailoring pain management to individual needs in palliative care. Table 2 outlines the common medicines used in palliative care.

| Medicine Group | Medicine Class | Example Medicines |

| Non-opioids | Paracetamol | Paracetamol oral tablets and liquid. Rectal suppositories, injectable |

| NSAIDs | Ibuprofen oral tablets and liquid

Ketoralac oral tablets and injectable Acetylsalicylic acid oral tablets and rectal suppositories |

|

| Opioids | Weak opioids | Codeine oral tablets and liquid and injectable |

| Strong opioids | Morphine oral tablet and liquid and injectable

Hydromorphone oral tablets and liquid and injectable Oxycodone oral tablets and liquid Fentanyl injectable, transdermal patch, transmucosal lozenge Methadone oral tablet, liquid, injectable |

|

| Adjuvants | Steroids | Dexamethasone oral tablet and injectable

Methylprednisolone oral tablets and injectable Prednisolone oral tablets |

| Antidepressants | Amitriptyline oral tablets

Venlafaxine oral tablets |

|

| Anticonvulsants | Carbamazepine oral tablets and injectable | |

| Bisphosphonates | Zoledronate injectable |

Non-Pharmacological Interventions

Non-pharmacological interventions can be useful in managing pain in palliative care by meeting patients’ psychological, social and spiritual needs in conjunction with analgesic medication (Franklin & Lovell, 2024). Recent reviews have highlighted a range of non-pharmacological interventions for palliative pain management. Ruano et al. (2022) found that mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, guided imagery, progressive muscle relaxation, and emotional and symptom-focused engagement (EASE) were the most effective psychological strategies for reducing cancer pain. Music therapy and brief cognitive behavioural strategies (CBS) showed potential but require further research, while coping skills training and yoga did not demonstrate significant benefits.

Complementing these findings, van Veen et al. (2024) found that massage therapy and virtual reality had the strongest evidence for pain relief. Other promising interventions included hypnosis, progressive muscle-relaxation-interactive-guided imagery, cognitive-behavioural audiotapes, wrapped warm footbaths, reflexology, and music therapy. However, mindful breathing, mindfulness-based stress reduction, aromatherapy, and aroma-massage therapy did not show significant effects. These findings underscore the importance of integrating evidence-based, non-pharmacological strategies into palliative care pain management.

Management of Physical Symptoms

In addition to pain, patients nearing the end-of-life often have other types of negative symptoms, including dyspnoea, cough, nausea and vomiting, constipation, anorexia and cachexia, dysphagia, fatigue, seizures, lymphoedema, depression, anxiety and terminal restlessness or delirium. Click or tap on the tabs below to learn more about these symptoms at the end of life.

At the time of impending death, nurses play a vital role in creating a peaceful and supportive atmosphere where families feel safe to express their cultural responses to death. This involves more than clinical care; it requires emotional presence, cultural sensitivity, and thoughtful communication. Nurses can dim harsh lighting, reduce noise, and arrange the space to feel more private and comforting. They can also facilitate rituals or practices important to the family’s beliefs, such as prayer, music, or the presence of spiritual leaders. By acknowledging and respecting diverse cultural expressions of grief, nurses help families feel seen and supported during one of life’s most vulnerable moments.

Caring for Spiritual Needs

Caring for the spiritual needs of palliative care patients is an essential component of comprehensive care. Spiritual needs are highly prevalent among palliative care patients, however, this is a part of care that is often overlooked or suboptimal (Büssing, 2024; Vivat, 2024). But what does spirituality really mean? The world consensus definition describes spirituality as: “a dynamic and intrinsic aspect of humanity through which persons seek ultimate meaning, purpose, and transcendence, and experience relationship to self, family, others, community, society, nature, and the significant or sacred. Spirituality is expressed through beliefs, values, traditions, and practices.” (Puchalski et al., 2014, p. 646). Spiritual care is deeply personal and will vary greatly from one individual to another. For this reason, assessing spiritual needs and spiritual wellbeing and engaging in meaningful conversations about what that looks like for each patient is essential (Büssing, 2024). Spiritual needs can be explored using assessment tools such as the Spiritual Needs Questionnaire (SpNQ-20) developed by Büssing (2010), which helps identify individual concerns, values, and sources of strength and meaning at the end of life. This assessment identifies four key dimensions of spiritual need: religious needs, needs for inner peace, existential needs, and the need to give to others (Büssing, 2010). Other structured conversation tools, such as HOPE (Sources of Hope, Organised religion, Personal practices, Effects on medical care) or FICA (Faith, Importance, Community, Interventions), remind clinicians of key areas to address (Leget, 2024; Vivat, 2024). Even just facilitating a discussion about spiritual needs can aid in addressing spiritual needs as they can remind patients of their spiritual strengths like meaning, connection, agency, hope and faith (Haufe et al., 2024). A somewhat structured way of getting into conversation can be making use of the two questions that were developed by Caresearch (2023a):

- Are you at peace?

- Where do you find strength in difficult times?

However you assess spiritual needs, spiritual care involves skills in communication, such as asking open-ended questions, being receptive and listening carefully in a nonjudgmental way, rather than speaking (Leget, 2024). Simply responding to a patient’s spiritual assessment, especially when it reveals distress or unmet needs, is a vital starting point for providing meaningful spiritual support (Vivat, 2024). It’s important to ensure a multi-disciplinary approach is implemented, integrating the patient’s spiritual needs into the comprehensive care plan, and making appropriate referrals to specialists like chaplains, ministers or other spiritual guides when needed (Büssing, 2024; Leget, 2024; Vivat, 2024).

Transitions Within and Between Services

Transitions in and between care settings are critical moments in the palliative and end-of-life care journey. Effective management of these transitions is essential to ensure continuity, safety, and person-centred care for people with life-limiting conditions and their families (ACSQHC, 2023; PCA, 2022). Click or tap on the tabs below for the principles for ensuring effective transitions of care.

Key actions for safe transitions include thorough preparation and anticipatory planning to ensure that patients, their families, and carers have continuous access to appropriate care, medications, and support, including after-hours assistance (PCA, 2022). Any significant changes, such as a transfer between wards, discharge home, or the death of a patient, should be communicated promptly within and between services to prevent distressing errors, such as inadvertently recalling a deceased person for appointments (PCA, 2022). Additionally, every transition of care should trigger a reassessment of the patient’s needs and preferences, ensuring that care remains aligned with their goals and current circumstances (PCA, 2022).

Grief Support

In palliative and end-of-life care, supporting families and carers through grief is a core responsibility of all health professionals, extending before, during, and after the death of a person with a life-limiting condition. Grief is a natural response to loss, and its course and consequences vary for each individual, shaped by personal, social, and cultural circumstances. Each person will react differently to anticipated and actual death. To understand how to support a person in their time of grief, you must first understand the different stages of grief that person might be in.

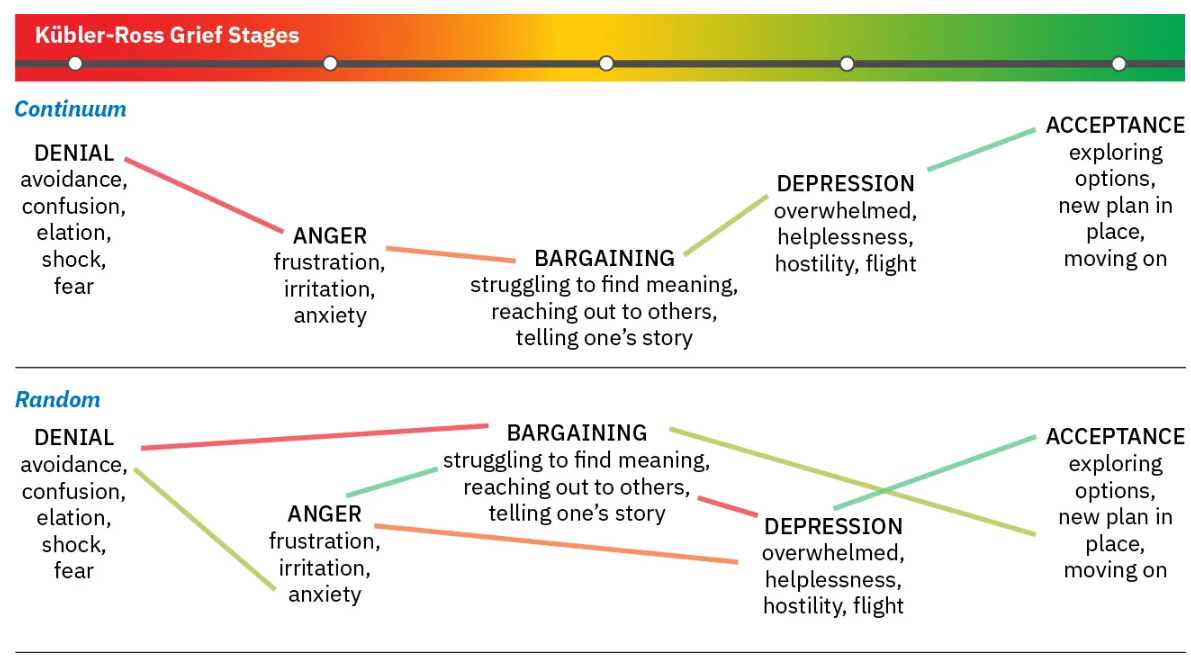

Navigating the Different Stages of Grief

In 1969, Dr Elisabeth Kübler-Ross wrote a book entitled On Death and Dying in which she outlined a conceptual framework for how individuals cope with the knowledge that they are dying (Kübler-Ross, 1997). She proposed five stages of this process that included denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. Not all people will go through each stage in sequence, and some may skip some stages altogether. It is important for nurses who care for patients who are dying to have an understanding of these stages to be able to properly care for and support themselves and their families.

Patients and families may experience these stages along a continuum, move randomly and repeatedly from stage to stage, or skip stages altogether. As the figure below illustrates, there is no correct way to grieve, and an individual’s needs and feelings must remain central to care planning.

Denial

Denial is the first stage because many individuals will initially react to being told that they may die by denying what they heard. People in this first stage will be in disbelief and think that their doctor has made some kind of mistake. Often, patients will go to another doctor for a second opinion during this stage. Denial can be important for two reasons: it will initially be somewhat of a shock absorber, enabling the person to seek clarification about the truth in what they were told. It can also provide patients with the needed time to become acquainted with the possibility that the information they heard is true, which can enable them to internalise and begin to process that information.

Anger

Anger is the second stage and can be the most difficult for clinicians and caregivers to witness. In this stage, individuals have accepted that the news of impending death is true, and they are naturally angry about it. They do not understand why they have to die, and they make this known to those around them. They may lash out at clinicians and loved ones alike because they are angry about their situation. Often, nothing that clinicians or family members do for them is right, and they have negative things to say about other aspects of their lives as well. Patients in this stage realise that they have lots of things in their life that they wanted to accomplish, but now they will not have the time.

Bargaining

The third stage is called bargaining, and it is a stage that is rarely visible to onlookers, as it happens internally within the person who is dying. In this stage, individuals realise that they are past denying that they are dying and that they have been angry about it, with neither of the two causing any change in the outcome. Patients at this stage may bargain with a higher power to change their outcome and give them more time. Sometimes patients might bargain with their doctor to try to find any other option that might give them more time, but this bargaining is often accomplished internally between the dying patient and their higher power or God.

Depression

Depression is the fourth stage and is a natural part of learning that impending death is near. Patients might be saddened because they had things they wanted to accomplish, places they wanted to go, or people they wanted to see, and those things will now be cut short. In addition, patients may be experiencing a decline in physical abilities, loss of function, and increased symptoms such as pain. Those are factors that can lead to depression even in people who are not dying, and are even more magnified in those who are dying. It is not uncommon for individuals in the depression stage of grief to experience irritability, sleeplessness, significant fatigue, and loss of focus or energy. Simple tasks such as getting out of bed, showering, or preparing a meal can feel so overwhelming that individuals withdraw from activity. They may struggle to find meaning in their life or to identify their sense of personal worth or the value of their contributions. Depression can be associated with ineffective coping behaviours, and nurses should watch for signs of self-medicating with alcohol or drugs to mask or numb depressive feelings.

Acceptance

The final stage is acceptance. This stage does not mean that the person is happy about their impending death, but rather that they have come to accept it and have found a sense of peace with it. The first four stages involved mostly negative emotions, which have taken a toll on the patient. Time has progressed, and patients can begin to move past the negative emotions and focus on the time they have left. During this stage, their hope for a cure is replaced by a hope that their final days will be peaceful and their death will be what they want it to be.

There are some important actions that nurses and clinicians can take during each of these stages to support the patient and their family. Click or press on each stage below to explore the nursing interventions that can assist with each stage.

Bereavement Support

Grief support should be tailored to the unique needs, values, and cultural backgrounds of families and carers. This includes recognising diverse definitions of family, such as chosen family, kinship networks, and friends (PCA, 2022). Support for grief and bereavement begins before death, with anticipatory guidance and preparation, and continues after death to help families adjust and cope (ACSQHC, 2023). In a recent scoping review, Coelho et al. (2025) outlined six stages of interventions for bereavement support in palliative care, ranging from initial patient admission through post-death bereavement, emphasising individualised assessment and tailored support to address the varying needs of grieving individuals. Press or click on the plus signs in the infographic below to understand each stage of bereavement support (Coelho et al., 2025).

Communication

Discussing end-of-life care can be challenging. These conversations often involve navigating complex emotions, uncertainty, and deeply personal values. Despite the difficulty, open and honest communication is vital to ensure that a person’s wishes are understood and respected. Initiating these discussions early offers significant benefits for both patients and their families. Research shows that early end-of-life conversations are linked to improved patient and healthcare outcomes, as well as a higher likelihood of receiving care aligned with personal preferences (Deckx, 2020; Nakazawa et al., 2025). Such conversations can reduce the use of aggressive medical interventions, often associated with diminished quality of life, and instead promote care that enhances comfort, mood, and overall satisfaction (Crawford et al., 2021; Nakazawa et al., 2025; Thomas et al., 2020). By documenting their values and preferences, patients can safeguard their autonomy and ensure that future healthcare decisions reflect their wishes, even if they lose the capacity to communicate (Crawford et al., 2021). In contrast, the absence of these discussions may lead to emotional isolation, heightened anxiety, and poorly managed pain (Sansom-Daly, 2022).

Families also benefit greatly from early end-of-life conversations. These discussions help prepare loved ones for the patient’s death, offering clarity and guidance during a difficult time (Thomas et al., 2020). When patients’ preferences, particularly for home-based care, are honoured, families report higher “good death” scores, including positive experiences such as dying in a favourite place, enjoying daily life, and spending meaningful time together (Nakazawa et al., 2025).

For healthcare providers and the broader system, early conversations help clarify patient goals, reduce unnecessary interventions, and strengthen the therapeutic relationship. They enable clinicians to better understand what matters most to patients, leading to more personalised and patient-centred care (Nakazawa et al., 2025; Thomas et al., 2020). Recognising the importance of early end-of-life conversations is only the first step. The next challenge lies in knowing how and when to initiate these discussions in a way that feels respectful, timely, and supportive. While there is no one-size-fits-all approach, understanding the principles of compassionate communication during end-of-life discussions can help clinicians and caregivers navigate these moments with confidence and care.

Initiating End-of-Life Discussions

Initiating an end-of-life discussion requires a thoughtful and well-prepared approach to ensure it is both patient-centred and effective. Preparation begins with assessing the patient’s readiness to engage in such conversations. This can be achieved by observing their emotional and psychological state, and by using open-ended questions to explore their feelings, concerns, and both verbal and non-verbal cues (Deckx et al., 2020). Non-verbal cues can include a patient’s overall demeanour and psychological presentation compared to their baseline. For example, observing signs of fear or denial in a patient’s body language or facial expressions can indicate their openness (or reluctance) to engage in such conversations. While clinicians may not always accurately predict readiness based on non-verbal cues alone, paying attention to these signals is part of a sensitive approach to understanding a patient’s comfort level and helping to pick the right time for these discussions (Deckx et al., 2020; Thomas et al., 2020).

Being able to gauge the readiness of a conversation about end-of-life preferences is important. Starting with open-ended questions can help create a safe and supportive space for patients to express their thoughts, values, and concerns. These questions not only guide the conversation gently but also allow clinicians to assess emotional readiness and tailor discussions to individual needs.

Below is a table of open-ended questions that can be used to initiate and navigate these sensitive conversations:

| Theme | Example Questions |

| Readiness and information preferences | “How much would you like to know about your condition?” “Would you like to talk about what might happen if your health changes?” |

| Support and emotional needs | “When you’re not feeling well, who do you like to have around for support?” “Some people say they feel alone even in a room full of people. Have you ever felt that way?” |

| Comfort and environment | “What brings you comfort when you’re feeling unwell?” “Do you prefer a quiet space, music, or something else when you’re resting?” |

| Decision-making preferences | “How are decisions about your care usually made?” “Have you thought about who you’d trust to make decisions if you couldn’t?” |

| Treatment preferences | “Are there any tests or treatments you’ve found especially difficult or would prefer to avoid?” “Have you ever thought about whether you’d want life-support treatments like a breathing machine?” |

| Family and relationships | “Do you ever worry more about your family than yourself?” “What would help your family feel supported if your health worsened?” |

| Spiritual beliefs | “Do you find comfort in any spiritual or religious beliefs or traditions?” |

| Cultural sensitivity | “Are there any cultural or family traditions that are important to you when thinking about your care?” “Would you prefer to have these conversations with your family present?” |

| Remembrance and legacy | “What would be most important to you if you were no longer here?” “Would you want a service? What kind? Who would you want to be there?” “If you wanted to leave a message or letter, who would it be for?” |

Clinicians should also be mindful of time management. While these discussions can be time-consuming, initiating them early often leads to more efficient care planning and can ultimately save time (Deckx et al., 2020; Thomas et al., 2020). Deckx et al. (2020) outline several entry points for introducing the topic, including responding to patient cues, incorporating discussions into routine care (such as during assessments or care planning), or addressing prognosis and potential deterioration directly. It is important to recognise that end-of-life conversations are rarely a one-off event. They typically unfold over multiple consultations, allowing for gradual exploration of sensitive topics and reducing the risk of overwhelming the patient (Deckx et al., 2020).

Cultural sensitivity is also essential. For diverse populations, such as older first-generation migrants or First Nations People, clinicians must be aware of cultural attitudes toward death, preferences for family-based decision-making, and the need for interpreters or translated materials to overcome communication and health literacy barriers (Gerber et al., 2020). Communication should be tailored to each individual, balancing gentleness with honesty, using clear and straightforward language, and avoiding assumptions based on age or cultural background (Deckx et al., 2020; Gerber et al., 2020).

Family involvement is another key component. Patients should be given the opportunity to include family members or nominated substitute decision-makers in these discussions. This not only supports shared understanding but also ensures that family perspectives are incorporated in a timely and structured way (Crawford et al., 2021; Deckx et al., 2020). Whatever the circumstances, end-of-life conversations should be person-centred, adapted to the individual’s level of health literacy, and revisited regularly to reflect changing needs and preferences (ACSQHC, 2023).

Supporting End-Of-Life Conversations with the PREPARED Framework

Initiating and navigating end-of-life discussions can be emotionally complex and clinically challenging. These conversations require sensitivity, empathy, and a structured approach to ensure that patients feel heard, respected, and empowered. The PREPARED framework and SPIKES framework offer clinicians a practical guide to approaching these discussions with confidence and compassion. These frameworks provide a step-by-step method for preparing, engaging, and responding to patients and families during these critical moments, helping to align care with individual values and preferences. You can access these frameworks via the links below.

Links to Learning

Documentation

Documentation in end-of-life (EOL) care is essential, as it supports patient autonomy and ensures that future healthcare decisions reflect the individual’s values and preferences, particularly if they lose the capacity to make decisions. As discussed earlier, end-of-life conversations are not just a one-time conversation. These conversations need to be happening and documented on a regular basis to ensure documentation reflects preferences and needs in the evolving situation (ACSQHC, 2023). Research shows that clear documentation is associated with a higher likelihood of patients receiving their preferred care, reduced use of aggressive or non-beneficial interventions, and improved quality of life and satisfaction (Crawford et al., 2021).

One key form of documentation is the Advance Care Directive (ACD), a legally binding document that allows individuals to express their healthcare preferences, appoint a substitute decision-maker, and formally refuse specific treatments. Despite its importance, ACD completion rates remain low in Australia, and integration within hospital systems is often poor (Crawford et al., 2021; Veltre et al., 2023). This can result in difficulties accessing the directive when it is most needed, and in some cases, the document may not adequately reflect the progression of illness or evolving health status.

To be effective, documentation must be clear, accessible, and embedded within clinical systems, while also remaining responsive to the patient’s changing condition and enduring values. Regular review and updates to care plans and directives are recommended to ensure they remain relevant and actionable throughout the patient’s healthcare journey (Crawford et al., 2021). Ensuring that documentation is clear, accessible, and integrated into the system, while remaining responsive to a patient’s health trajectory and enduring values. There are more and more tools out there to help us initiate and document these processes. Pathways such as the 7-Step Pathway developed by South Australia Health specifically for patients nearing the end of their lives, can help to guide clinicians through the appropriate clinical, legal and ethical steps in the correct order, and allows decisions to be documented, standardised and recognised (SA Health, 2024). Press or click on the tabs below for a summary of the 7-step pathway for a resuscitation plan.

Ethical Considerations at End-of-Life

Ethics in death and dying is a recurring topic in the medical community. It is also routinely addressed in legislation where national and state laws are set and often challenged based on varying ethical standards. As with any ethical conflict, considerations include autonomy (the right of independence), beneficence (to do good), nonmaleficence (to do no harm), and justice (fairness). Many of the preceding advance directives seek to ensure an ethical death in that quality of life is maximised and the decision made by others on behalf of a dying individual aligns with their values, beliefs, and cultural conditions. While nurses may be ethically challenged when caring for a dying patient, they must be informed and comfortable supporting patients and families in end-of-life situations.

Terminal Weaning

Removing or discontinuing life-sustaining treatments and procedures is referred to as terminal weaning, also known as terminal extubation. This process can present a significant ethical dilemma for the patient’s family, carers, and healthcare decision-makers, as it often involves complex considerations around the patient’s wishes, quality of life, prognosis, and cultural or religious beliefs. Navigating these decisions requires sensitive communication, ethical guidance, and a multidisciplinary approach to ensure that care remains compassionate and aligned with the patient’s values and best interests. It is important to note that terminal weaning is not the same as euthanasia; rather, it involves allowing the natural progression of a terminal condition without artificially prolonging life. Most terminal weaning takes place in an intensive care unit (ICU) setting with the removal of ventilator tubes or other life-sustaining equipment. Terminal weaning occurs after a determination is made by providers that continued treatment will not improve or reverse the condition of the individual, and the intubation is only prolonging the dying process (Thellier et al., 2017). The patient’s family ultimately makes the decision based on the provider’s recommendations and facts about the prognosis for ongoing life. The time between terminal weaning and death is typically very short. Terminal weaning occurs in the presence of providers and nurses to ensure the patient’s comfort level is maximised, usually using palliative sedation and pain medication, and the family has adequate support.

Palliative Sedation

The administration of pharmaceutical agents to reduce consciousness with the aim of reducing discomfort and distress at end-of-life is known as palliative sedation (Cherny, 2024). These medications may be administered intravenously, subcutaneously, orally, or rectally. Palliative sedation is appropriate in the case of severe and intractable pain at the end of life, and it can be used in the ICU, inpatient hospice, inpatient general units, and at home, depending on the circumstances of each individual. Palliative sedation allows restfulness for the individual and reduces stress levels for the family (Cherny, 2024). Discomfort and pain in palliative care may result from the disease process itself or as a result of palliative treatments, procedures, or surgical interventions. However, palliative sedation is more than just administering pain relievers. Palliative sedation may also relieve emotional suffering, such as anxiety, and reduce physical discomfort, such as breathlessness or dyspnea. It can also alleviate symptoms of delirium and fatigue.

While both euthanasia and palliative sedation may use similar modalities, the distinction lies in the intention and the outcome. Palliative sedation intends to provide comfort and focuses on the ethical standards of beneficence and nonmaleficence. The outcome of palliative sedation is improved quality of life during the end-of-life period rather than inducing or hastening the process of death. Nurses need to assess their comfort level in providing this care during this challenging time, as there is a shift from delivering curative treatment to maintaining and providing dignity and comfort at the end of life.

Voluntary Assisted Dying

Voluntary assisted dying (VAD) is now legally available in all six Australian states: Victoria, Western Australia, Tasmania, South Australia, Queensland, and New South Wales. Each state has its own legislation outlining eligibility criteria and procedural safeguards. In these jurisdictions, VAD allows a competent adult with a terminal illness to request and receive medication to end their life, either through self-administration or practitioner administration (by a doctor, or in some States, a nurse practitioner or registered nurse). The Australian Capital Territory (ACT) passed its VAD legislation on 5 June 2024, with the law set to commence on 3 November 2025. In contrast, VAD remains illegal in the Northern Territory, where assisting another person to die may result in serious criminal charges (Queensland University of Technology, 2025)

Each state and territory has different legislation related to VAD, therefore, as a nurse, it is important to understand the legal boundaries of the role in VAD processes. For example, in Queensland, registered nurses may:

- Provide information about VAD only when requested

- Participate in VAD processes if trained and authorised

- Continue to provide holistic care to patients accessing VAD, including palliative and psychosocial support. (Queensland Government, 2021)

The Australian College of Nursing (ACN) recognises the ethical complexity of VAD and encourages nurses to:

- Respect patient autonomy, dignity, and informed choice

- Provide compassionate, person-centred care regardless of personal beliefs

- Exercise conscientious objection if participation conflicts with personal, cultural or religious values, while ensuring continuity of care. (ACN, 2021)

Clinical and Legal Responsibilities at End-of-Life

Verification of Death

Verification of death is the clinical process of confirming that a person has died. In Australia, this can be performed by a medical practitioner (doctor), registered nurse, registered midwife, or qualified paramedic, particularly in palliative care settings where death is expected. The process involves a clinical assessment to confirm the irreversible cessation of cardiorespiratory function, which includes checking for the absence of a pulse, heart sounds, breath sounds, pupillary response to light, and response to painful stimuli. A minimum observation period (often five minutes) is required to ensure that these signs are absent before death is verified. The time of death is then recorded, and a Verification of Death form must be completed according to state or territory policy (Caresearch, 2023b).

Medical Certificate of Cause of Death

Certification of death is a separate legal process that involves formally diagnosing the cause of death and completing the Medical Certificate of Cause of Death (MCCD). Only a medical practitioner who knows the patient’s medical history and is prepared to certify the cause and circumstances of death can complete the MCCD. This certificate is a legal requirement under the Births, Deaths and Marriages Registration Act and is necessary for registering the death with the relevant state or territory authority (ABS, 2024; Caresearch, 2023b).

Coroners Cases

If the death is a Coroner’s case, additional legal steps must be followed. If the death is reportable to the Coroner (for example, if it is unexpected, unexplained, or due to certain circumstances), a Coronial Checklist or additional documentation must also be completed, and the case referred to the Coroner (ABS, 2024). In cases where a death is reportable to the Coroner, nurses may be required to assist in gathering information for the Coronial Checklist and ensure that the body is not disturbed until the Coroner or their representative provides further instructions.

Organ Donation