Pressure Injury Prevention and Management

Sandra Dash and Kate Hurley

Learning Outcomes

In this chapter you will learn how to:

- Identify people at risk of developing pressure injuries

- Describe the stages of pressure injury development

- Describe interventions to prevent and manage pressure injuries

- Document actions taken and observations of pressure injuries using appropriate tools.

Pressure Injuries

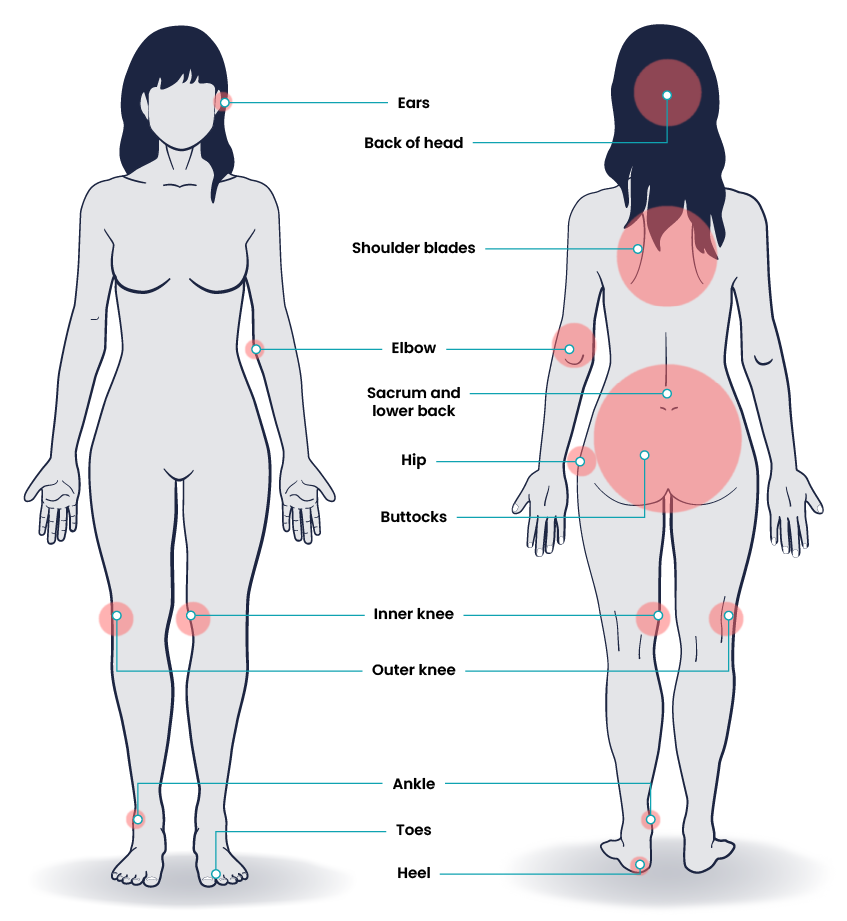

Pressure injuries occur when there is prolonged pressure, especially over bony prominences, causing localised damage to the skin or underlying soft tissue. Pressure injuries generally form when the skin layer of tissue gets caught between an external hard surface, such as a chair, and the internal hard surface of the bone. Pressure injuries are commonly found on the sacrum, heels, ischia, and coccyx.

Risk Factors

There are many risk factors that can cause pressure injuries:

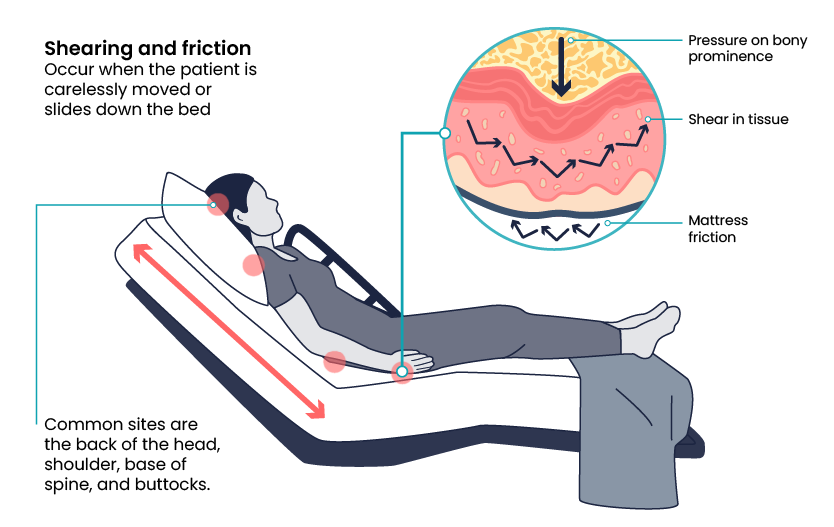

Friction and shear are common factors that cause a patient to develop a pressure injury in the healthcare setting. See Figure 1 for a visual representation of how friction and shear can impact skin integrity.

Common Pressure Injury Sites

Pressure injuries can occur over any bony prominences, especially areas such as heels, elbows, hips, buttocks and the sacrum. However, pressure injuries can also occur on any area that has continued pressure.

Pressure Injury Assessment

To correctly assess whether a wound is a pressure injury, several elements need to be noted, such as:

- Location of the pressure injury

- Size in centimetres with the height being from head to toe and length being from side to side. The depth is also measured using a cotton-tipped swab

- Presence of undermining or tunnelling

- The stage of the pressure injury

- The colour of the pressure injury/wound bed and location of any necrosis or eschar

- Integrity of the surrounding skin

- Any signs of infection.

Assessment Tools

Braden Scale

The Braden Scale is a standardised, evidence-based assessment tool commonly used in the healthcare setting to assess and document a patient’s risk for developing pressure injuries.

Scoring

Several factors place a patient at risk for developing pressure injuries, including nutrition, mobility, sensation, and moisture. The Braden Scale is a tool commonly used in health care to provide an objective assessment of a patient’s risk for developing pressure injuries. The six risk factors included on the Braden Scale are sensory perception, moisture, activity, mobility, nutrition, and friction/shear, and these factors are rated on a scale from 1-4 with 1 being “completely limited” to 4 being “no impairment.” The scores from the six categories are added, and the total score indicates a patient’s risk for developing a pressure injury.

- Mild risk = 15–18

- Moderate risk = 13–14

- High risk = 10–12

- Severe risk = less than 9.

Nurses create care plans using these scores to plan interventions that prevent or treat pressure injuries.

Sensory Perception

The sensory perception risk factor is defined as the ability to respond meaningfully to pressure-related discomfort. If a patient is unable to feel pressure-related discomfort and respond to it appropriately by moving or reporting pain, they are at high risk of developing a pressure injury. This risk category describes two different issues that affect sensory perception. The first description refers to the patient’s level of consciousness, and the second description refers to the patient’s ability to feel cutaneous sensation. See Table 1 for a description of each level of risk and their associated interventions.

| Assessment Category | Rating Description | Interventions |

|

Sensory

|

4 – No Impairment: Responds to verbal commands. Has no sensory deficit that would limit ability to feel or voice pain or discomfort. |

|

|

3 – Slightly Limited: Responds to verbal commands but cannot always communicate discomfort or the need to be turned. OR Has some sensory impairment that limits the ability to feel pain or discomfort in 1 or 2 extremities.

|

|

|

|

2 – Very Limited: Responds only to painful stimuli. Cannot communicate discomfort except by moaning or restlessness. OR Has a sensory impairment that limits the ability to feel pain or discomfort over half of the body.

|

All interventions mentioned in 3 – Slightly Limited plus:

|

|

|

1 – Completely Limited: Unresponsive (does not moan, flinch, or grasp) to painful stimuli, due to diminished level of consciousness or sedation. OR Limited ability to feel pain over most of the body.

|

All interventions mentioned in 2 – Very Limited plus:

|

Moisture

The moisture risk factor is defined as the degree to which skin is exposed to moisture. Prolonged exposure to moisture increases the probability of skin breakdown. Moisture can come from several sources, such as perspiration, urine incontinence, stool incontinence, or wound drainage. Frequent surveillance, removal of wet or soiled linens, and use of protective skin barriers greatly reduce this risk factor. See Table 2 for a description of the level of moisture and their associated interventions.

| Assessment Category | Rating Description | Interventions |

|

Moisture

|

4 – Rarely Moist: Skin is usually dry; linen only requires changing at routine intervals.

|

|

|

3 – Occasionally Moist: Skin is occasionally moist, requiring an extra linen change approximately once per day.

|

All interventions mentioned in 4 – Rarely Moist plus:

|

|

|

2 – Often Moist: Skin is often but not always moist. Linen must be changed at least once per shift.

|

All interventions mentioned in 3 – Occasionally Moist plus:

|

|

|

1 – Constantly Moist: Skin is kept moist almost constantly by perspiration, urine, etc. Dampness is detected every time the patient is moved or turned.

|

All interventions mentioned in 2 – Often Moist plus:

|

Activity

The activity risk factor is defined as the degree of physical activity. For example, walking or moving from a bed to a chair reduces the risk of developing a pressure injury by redistributing pressure points and increasing blood and oxygen flow to areas at risk. The level of activity is defined by how frequently the patient is able to get out of bed, move into a chair, or ambulate with or without help. See Table 3 for a description of each level of risk and their associated interventions.

| Assessment Category | Rating Description | Interventions |

|

Activity

|

4 – Walks Frequently: Walks outside the room at least twice a day and inside the room at least once every two hours during waking hours.

|

|

|

3 – Walks Occasionally: Walks occasionally during the day, but for very short distances, with or without assistance. Spends the majority of each shift in bed or chair.

|

|

|

|

2 – Chair Fast: Ability to walk is severely limited or nonexistent. Cannot bear their own weight and/or must be assisted into chair or wheelchair.

|

|

|

|

1 – Bedfast: Confined to bed.

|

|

Mobility

The mobility risk factor is defined as the patient’s ability to change or control their body position. For example, healthy people frequently change body position by rolling over in bed, shifting weight in a chair after sitting too long, or by moving their extremities. However, tissue damage will occur if a patient is unable to reposition on their own power unless caregivers frequently change their position. See Table 4 for a description of each level of risk for mobility and their associated interventions.

| Assessment Category | Rating Description | Interventions |

|

Mobility

|

4 – No Limitations: Makes major and frequent changes in position without assistance.

|

|

|

3 – Slightly Limited: Makes frequent though slight changes in body or extremity position independently.

|

|

|

|

2 – Very Limited: Makes occasional slight changes in body or extremity position but unable to make frequent or significant changes independently.

|

|

|

|

1 – Completely Immobile: Does not make even slight changes in body or extremity position without assistance.

|

Same interventions as for 2 – Very Limited |

Nutrition

Adequate nutrition and fluid intake are vital for maintaining healthy skin. Protein intake, in particular, is very important for healthy skin and wound healing. The nutrition risk factor is defined by two categories of descriptions. The first category measures the amount and type of oral intake. The second category is used for patients receiving tube feeding, total parenteral nutrition (TPN), or are prescribed clear liquid diets or nothing by mouth (NBM). See Table 5 for a description of each level of risk for nutrition and their associated interventions.

| Assessment Category | Rating Description | Interventions |

|

Nutrition

|

4 – Excellent: Eats most of every meal. Never refuses a meal. Usually eats a total of 4 or more servings of meat and dairy products. Occasionally eats between meals. Does not require supplementation.

|

|

|

3 – Adequate: Eats over half of most meals. Eats a total of 4 servings of protein (meat and dairy products) each day. Occasionally refuses a meal, but will take a supplement if offered OR Is on a tube feeding or TPN regimen that most likely meets most of nutritional needs

|

|

|

|

2 – Probably Inadequate: Rarely eats a complete meal and generally eats only about half of any food offered. Protein intake includes only 3 servings of meat or dairy products per day. Occasionally will take a dairy supplement OR Receives less than optimum amount of liquid diet or tube feeding.

|

All interventions mentioned in 3 – Adequate plus:

|

|

|

1 – Very Poor: Never eats a complete meal. Rarely eats more than one third of any food offered. Eats two servings of protein (meat or dairy products) per day. Takes fluids poorly. Does not take a liquid dietary supplement OR Is NPO and/or maintained on clear liquids or IV for more than 5 days.

|

All interventions mentioned in 2 – Probably Inadequate plus:

|

Friction/Shear

Friction and shear are significant risk factors for producing pressure injuries. This section is scored based on whether an individual has a problem, potential problem, or no apparent problem in this area. See Table 6 for a description of each level of risk for friction/shear and their associated interventions.

| Assessment Category | Rating Description | Interventions |

| Friction/shear

|

3 – No Apparent Problem: Moves in bed and chair independently and has sufficient muscle strength to lift up completely during move. Maintains good position in bed or chair at all times.

|

Keep bed linens clean, dry, and wrinkle-free. |

|

2 – Potential Problem: Moves feebly or requires minimal assistance. During a move, skin probably slides to some extent against sheets, chair, restraints, or other devices. Maintains a relatively good position in a chair or bed most of the time but occasionally slides down.

|

All interventions mentioned in 3 – No Apparent Problem plus:

|

|

|

1 – Problem: Requires moderate to maximum assistance in moving. Complete lifting without sliding against sheets is impossible. Frequently slides down in bed or chair, requiring frequent repositioning with maximum assistance. Spasticity, contractures, or agitation leads to almost constant friction.

|

All interventions mentioned in 2 – Potential Problem plus:

|

Link to Learning

Follow the link to this copy of the Braden Risk Assessment Tool. You may find others with a simple internet search. To complete each component of the tool, watch Pressure Wounds: The Braden Scale [5:15].

Waterlow Scale

The Waterlow assessment tool is one of three assessment scales used to determine the risk of pressure injury. (See an example of the tool used by Queensland Health). The Waterlow is used within the first eight hours of admission with repeated assessments throughout the admission as required (Queensland Health, 2019). The assessment tools used for assessing pressure injuries are part of the Comprehensive Care Standard (Standard 5) of the National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards (NSQHS). The Comprehensive Care Standard aims to provide care that meets the individual needs of the patient and ensures that harm is prevented. There are several sections within this standard that pertain specifically to pressure injuries.

- Action 5.10: This action identifies patients at risk of pressure injuries and plans for comprehensive care.

- Action 5.12: This action ensures that the risk factors and decisions regarding care are documented.

- Action 5.21: The organisation has systems for prevention and management of pressure injuries that follow best practice guidelines.

- Action 5.22: Clinicians providing care for patients at risk of pressure injuries conduct skin assessments within a timely manner as indicated in best practice guidelines.

- Action 5.23: The health organisation is required to provide education to patients and families on pressure injuries. Equipment used to prevent pressure injuries is based on best practice guidelines. (Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care, 2024)

These actions are incorporated into hospitals, day procedure services, MPS and small hospitals.

Staging Pressure Injuries

Pressure injuries commonly occur on the sacrum, heels, ischial tuberosity, and coccyx. In 2021 in Australia, an advisory panel of national experts formed the Australian Pressure Injury Treatment Advisory (PITA) group. This group developed a guideline to assess and manage pressure injuries. Pressure injuries are staged based on the extent of tissue damage. For example, Stage 1 pressure injuries have reddened but intact skin and Stage 4 pressure injuries have deep, open ulcers affecting underlying tissue and structures such as muscles, ligaments, and tendons. See the interactive below for an image and description of the stages of pressure injuries.

Prevention and Treatment

Strategies for Prevention

There are many strategies that can be implemented to prevent pressure injuries, including:

- Maintain regular skin inspections every day and with each repositioning or turn, monitor for signs of pressure injury, with a particular focus on high-risk areas such as bony prominences.

- Skin hygiene should be maintained to preserve skin integrity, including removing soiled clothing, providing a stable environment and consistent temperature, maintaining skin integrity and moisture and a normal pH level.

- Prevent friction and shear by elevating the foot of the bed to reduce the risk of the patient sliding. Use correct manual handling techniques, including slide sheets or equipment to transfer patients to reduce the level of risk of friction and shear. See Figure 4 for a suitable position for a patient resting in bed.

- Monitor nutrition and hydration status and refer the patient to a dietician if there are concerns about the nutritional status of a patient.

- Avoid rubbing or massaging bony prominences as this increases the risk of tissue damage. Using pressure relieving devices such as pillows or foam wedges can reduce pressure if used correctly. See Figure 5 for a wedge used to relieve pressure on the heels of a patient.

Support Surfaces

Pressure injury prevention and management requires a collaborative approach. The patient’s risk status and risk factors provide a foundation for an individualised care plan that can record their risk of developing pressure injuries or manage already developed pressure injuries. An optimal support surface is one that relieves pressure, shear and friction and maintains a stable skin temperature (Australian Wound Management Association [AWMA] et al., 2012). Speciality beds and sleeping surfaces are designed for patients at a very high risk of pressure injury and are recommended in cases where patients are either prone to developing a pressure injury (previous pressure injuries, age, skin integrity) or have a pressure injury that is being actively treated.

Comfort Equipment

Comfort equipment is suitable for those patients who are at low risk of developing a pressure injury and include overlays and cushions filled with foam, gel or air. These devices increase the level of comfort a patient experiences and may provide a degree of pressure reduction and reduce shearing and friction due to their low-resistance or non-abrasive properties (Parker & Kaim, 2021).

Constant Low-Pressure Devices

Constant low-pressure devices conform to body contours and aim to redistribute weight over a wider area, thereby reducing tissue interface pressure (AWMA et al., 2012 ). These devices may be powered or non-powered and include foam-filled mattresses, water beds, air overlays and mattresses with both a static/constant air and low-air-loss (Parker & Kaim, 2021). See Figure 6 for an image of a foam mattress commonly used in healthcare organisations.

Alternating Pressure Devices

Alternating pressure devices generate alternating high and low pressure between the body and the support surface by periodically deflating air cells under the body and redistributing the pressure on the tissue, which encourages perfusion (Queensland Health, 2009). These support surfaces are most appropriate for those at a very high risk of pressure injury and are recommended in cases where patients are either prone to developing a pressure injury (previous pressure injuries, age, skin integrity) or have a pressure injury that is being actively treated.

Ongoing Management and Treatment

The ongoing management and treatment of pressure injuries is multifactorial including:

- Promoting adequate nutrition

- Maintaining skin hygiene through the application of barrier films

- Keeping skin clean and dry and minimal use of powders and lotions

- Limiting massage over bony prominences

- Avoiding skin trauma by ensuring wrinkle-free linen

- Correct turning procedures (using lifting devices or slide sheets)

- Frequent turning (every 2 hours)

- Using supportive devices such as air-alternating mattresses, memory foams, pillows or heel protectors to support the tissue over bony prominences.

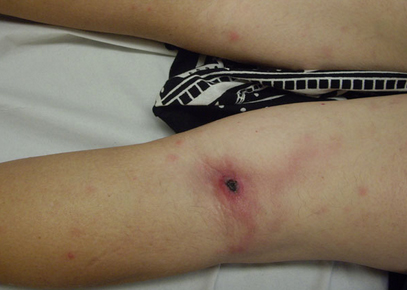

Kennedy Ulcer

The Kennedy ulcer is not a pressure injury like the others already mentioned. Kennedy ulcers occur at the end of life as part of the dying process due to end-of-life disease, hypoperfusion and multiorgan failure. A Kennedy ulcer can occur on any part of the body; however, the most common sites include sacrum and coccyx. Kennedy ulcers will occur regardless of the assessments and preventative measures applied. The Kennedy ulcer remains a misunderstood phenomenon with lack of awareness of correct diagnosis, clinical research and understanding of the etiology.

Key Takeaways

In this chapter, we covered:

- Pressure injuries occur when there is prolonged pressure causing localised damage to the skin or underlying soft tissue.

- Many risk factors can cause pressure injuries, including friction, shear, immobility, nutritional status, incontinence, mental status, age and chronic conditions.

- The Braden Scale and Waterlow Tool are two common pressure injury assessment tools used in the Australian healthcare context.

- A staging system is used to categorise pressure injuries with stage 1 involving intact skin that is non-blanchable and stage 4 involving full-thickness tissue loss. Unstageable pressure injuries occur when the extent of tissue damage cannot be defined due to the amount of slough or eschar present.

- To prevent pressure injuries, conduct regular skin assessments, use appropriate support surfaces to alleviate pressure(low-pressure devices or gel cushions), maintain skin hygiene, prevent friction and shear, monitor nutrition and hydration and avoid rubbing or massaging at-risk areas (bony prominences).

References

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. (2024). Comprehensive care standard. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/standards/nsqhs-standards/comprehensive-care-standard

Australian Wound Management Association, New Zealand Wound Care Society, Hong Kong Enterostomal Therapists Association & Wound Healing Society of Singapore. (2012). Pan Pacific clinical practice guideline for the prevention and management of pressure injury. https://www.nzwcs.org.nz/images/publications/2012_AWMA_Pan_Pacific_Abridged_Guideline.pdf

Parker, C., & Kaim, K. (2021). Optimising skin integrity and wound care. In Crisp, J., Douglas, C., Rebeiro, G., Waters, D. Potter & Perry’s Fundamentals of Nursing Australia and New Zealand 6th edition. Elsevier.

Queensland Health (2009). Pressure ulcer prevention and management resource guidelines 2009. Queensland Health Patient Safety Centre.

Chapter Attribution

This chapter has been adapted in parts from:

Nursing fundamentals 2e (n.d.) by Open Resources for Nursing, Chippewa Valley Technical College, is used under a CC BY licence.

Media Attributions

- Shear Force and Friction © Eileen Siddins is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Pressure Injury Sites © Eileen Siddins is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Pressure Injury © José M. Ramos , Isabel Jado, Sergio Padilla, Mar Masiá, Pedro Anda, and Félix Gutiérrez is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Fowler’s Position © Ben Green is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Foot Over Pillow © Sandra Dash is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Foam Matress © Sandra Dash is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Foam Dressing © Sandra Dash is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license