Assessing and Supporting Elimination

Kate Hurley and Sandra Dash

Learning Outcomes

In this chapter you will learn how to:

- Describe the different components of the urinary system and gastrointestinal system

- Recognise common complications in elimination and understand how to promote urinary and bowel elimination

- Examine lifespan considerations and how these can impact the elimination system

- Describe general ostomy care and identify the common sites for stoma formation

- Understand fluid balance and document actions and observations appropriately on recognised tools.

Introduction

Elimination is a basic human function of excreting waste through the bowel and urinary system. The process of elimination depends on many variables and intricate processes that occur within the body. Many medical conditions and surgeries can adversely affect the processes of elimination, so nurses must facilitate their patients’ bowel and urinary elimination as needed. Common nursing interventions related to facilitating elimination include inserting and managing urinary catheters, obtaining urine specimens, caring for ostomies, providing patient education to promote healthy elimination, and preventing complications. In this chapter, we will discuss the technical skills used to support bowel and bladder function, as well as the application of the nursing process while doing so.

Basic Concepts

Before discussing specific procedures related to facilitating bowel and bladder function, let’s review basic concepts related to urinary and bowel elimination. When facilitating alternative methods of elimination, it is important to understand the anatomy and physiology of the gastrointestinal and urinary systems, as well as the adverse effects of various conditions and medications on elimination. Use the information below to review these topics.

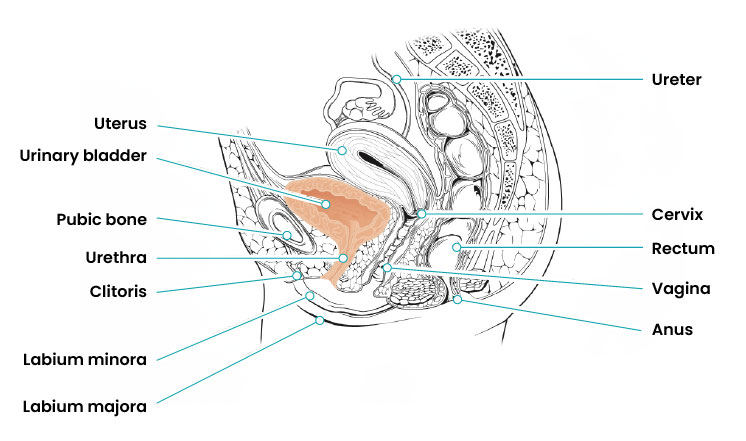

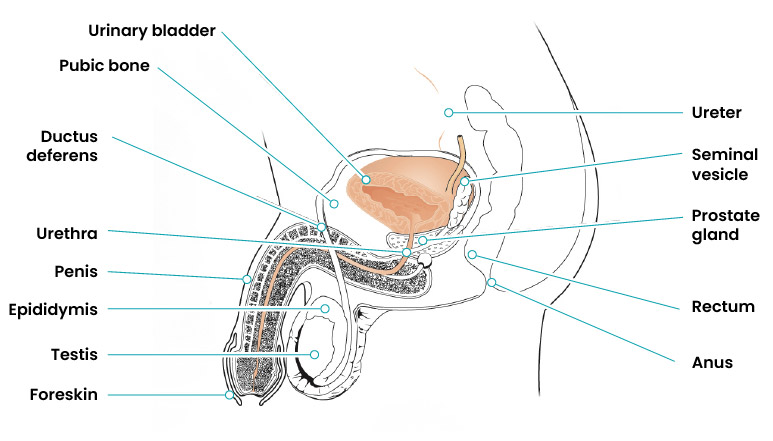

Urinary System

The urinary system, also referred to as the renal system or urinary tract, consists of the kidneys, ureters, bladder, and urethra. The purpose of the urinary system is to eliminate waste from the body, regulate blood volume and blood pressure, control levels of electrolytes and metabolites, and regulate blood pH. The kidneys filter blood in the nephrons and remove waste in the form of urine. Urine exits the kidney via the ureters and enters the urinary bladder, where it is stored until it is expelled by urination (also referred to as voiding or micturition). See Figures 1 and 2 for an image of the female and male urinary system.

A healthy adult with normal kidney function produces 800-2,000 mL of urine per day, depending on fluid intake, as well as the amount of fluid lost through sweating and breathing. A bladder can hold approximately 350 – 500mLs of urine at any time and when emptied there should be no residual urine remaining. Normal urine should be clear, pale to light yellow in colour, and not foul-smelling. However, some foods or medications may change the smell or colour of urine. Infections such as a urinary tract infection will change the colour of the urine to a darker colour and will produce an odour. Nurses frequently monitor and document a patient’s urine output as part of the overall plan of care. This nurse may use various devices such as urinals, pans, specifically designed containers, and catheters to capture and measure urine amount accurately. For infants and toddlers, the number of daily wet nappies provides a general measure of urine output.

Lifespan Considerations

|

|

Newborns Bowels: Meconium-first bowel movement. Other bowel movements depend on the mode of feeding. Urine: Urination could be anywhere between every 1–3 hrs or 4–6 times per day. IDC (indwelling catheter): Parent/caregiver must be present when inserting. |

|

|

Toddlers Bowels: Toilet training period. Urine: Toilet training period. Enuresis occurs (bed wetting). Limited verbal communication and immature neuromuscular control. IDC (indwelling catheter): Parent/caregiver must be present when inserting. |

|

|

Children Bowels: Risk of constipation due to not going at school. Urine: Peer pressure on bathroom habits at school, body image concerns, and irregular fluid intake. IDC (indwelling catheter): Parent/caregiver must be present when inserting. Blowing into straws helps relax pelvic muscles. |

|

|

Adults Bowels: At risk of lifestyle changes such as Crohn’s disease, diverticulitis and irritable bowel syndrome. Urine: Females have risk of urinary incontinence and males have risk of urgency and urinary retention. Work, study, and social activities can affect voiding patterns. Limited restroom access in some jobs. IDC (indwelling catheter): Female genital mutilation and childbirth can alter anatomy. |

|

|

Older Adults Bowels: Peristalsis slows and there is risk of constipation. Urine: Increased risk of UTIs. Age-related muscle weakening. Reduced mobility. Increased medication use. Diminished sensory perception. Chronic conditions and comorbidities. IDC (indwelling catheter): Possible urogenital tissue atrophies in older women.

|

Urinary Elimination Devices

This section will focus on the devices used to facilitate urinary elimination. Some common types of devices used to collect waste will be presented, including a focused section on urinary catheterisation.

A patient hospitalised without a urinary catheter, can eliminate waste (urine or faeces) with the assistance of various other aids. A bed pan is an continence aid that is regularly used to toilet patients who are not able to mobilise to the toilet, either as a result of surgery or other medical conditions. Figure 3 shows one type of bed pan. This particular bed pan is referred to as a slipper pan and has a cardboard insert which is easily destroyed in the macerator or sluice after use. This pan “slips” under the patient whilst they are lying down and can easily be removed once the patient has eliminated their waste (urine and/or stool).

A commode chair is another type of continence aid that is mobile and on wheels (Figure 4). This device is appropriate for a patient who is unable to mobilise or finds mobilisation difficult. For ease of use, the chair can be wheeled over the toilet, the brakes on the wheels engaged, giving the patient privacy to eliminate their bowels and/or bladder.

A male urine bottle is another commonly used continence aid (Figure 5) for patients that are not able to void into the toilet or are required to measure the amount of urine they are passing. This elimination device works by placing the penis into the top of the bottle and collecting the urine eliminated from the patient. The measurement indicators on the side of the bottle making this device appropriate to use if there is a requirement to measure the urine output of a patient. This urinary device can only be used by male patients and should only be used on individuals who are alert and conscious of their movements, as the bottles can spill easily.

Urinary Catheters

Urinary catheterisation is the insertion of a catheter tube into the urethral opening and placing it in the neck of the urinary bladder to drain urine. There are several types of urinary elimination devices, such as indwelling catheters, intermittent catheters, suprapubic catheters, and external devices. Each of these types of devices is described in the following subsections.

Indwelling Catheter

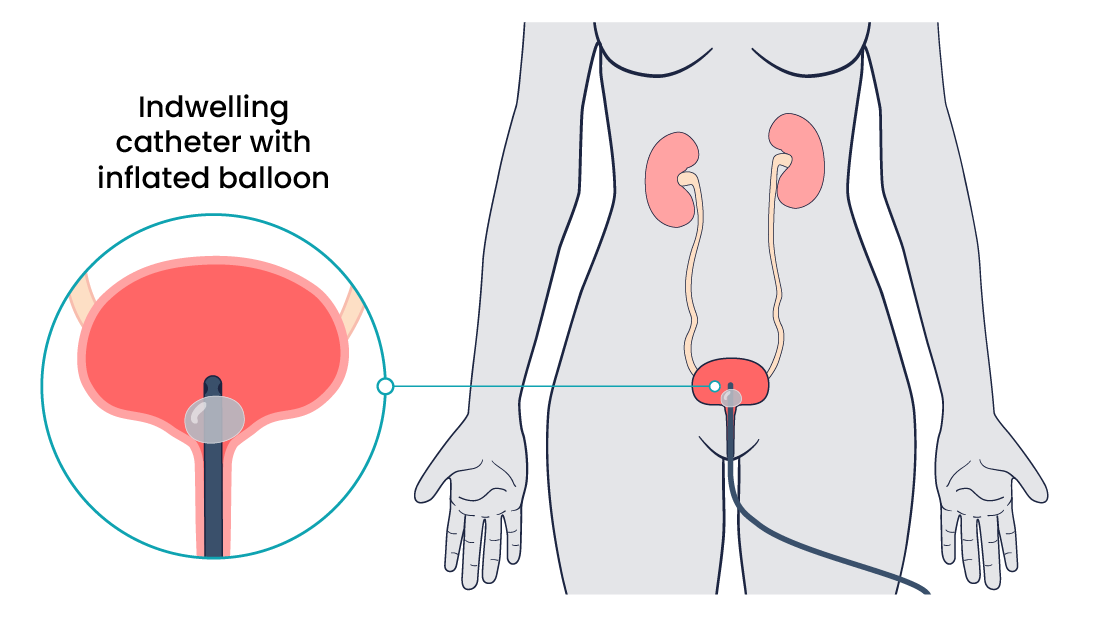

An indwelling catheter, often referred to as a “Foley catheter,” refers to a urinary catheter that remains in place after insertion into the bladder for the continual collection of urine. It has a balloon on the insertion tip to maintain placement in the neck of the bladder. The other end of the catheter is attached to a drainage bag for the collection of urine. See Figure 6 for an illustration of the anatomical placement of an indwelling catheter in the bladder neck.

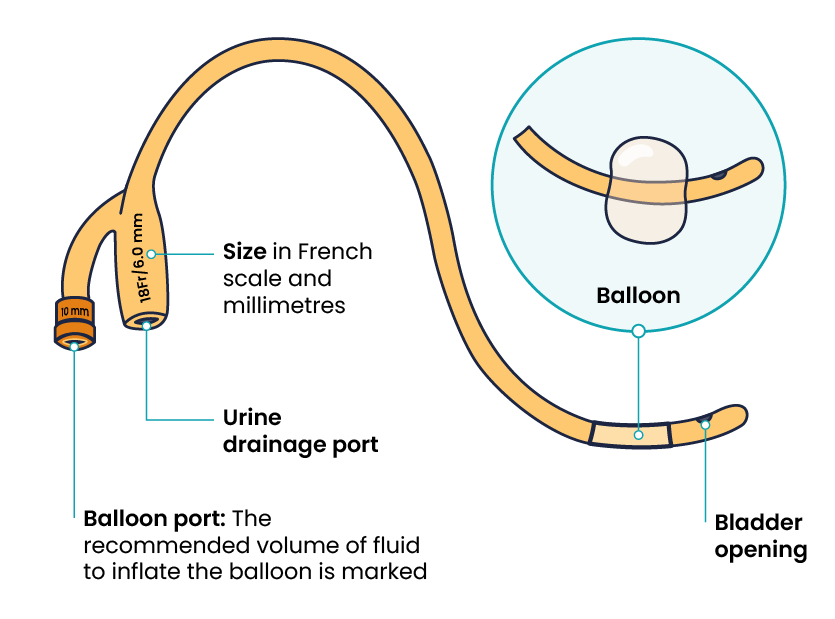

The distal end of an indwelling catheter has a urine drainage port that connects to a drainage bag. The size of the catheter is marked at this end using the French catheter scale. A balloon port is also located at this end, where a syringe is inserted to inflate the balloon after it is inserted into the bladder. The balloon port is marked with the amount of fluid required to fill the balloon. See Figure 7 for an image of the parts of an indwelling catheter.

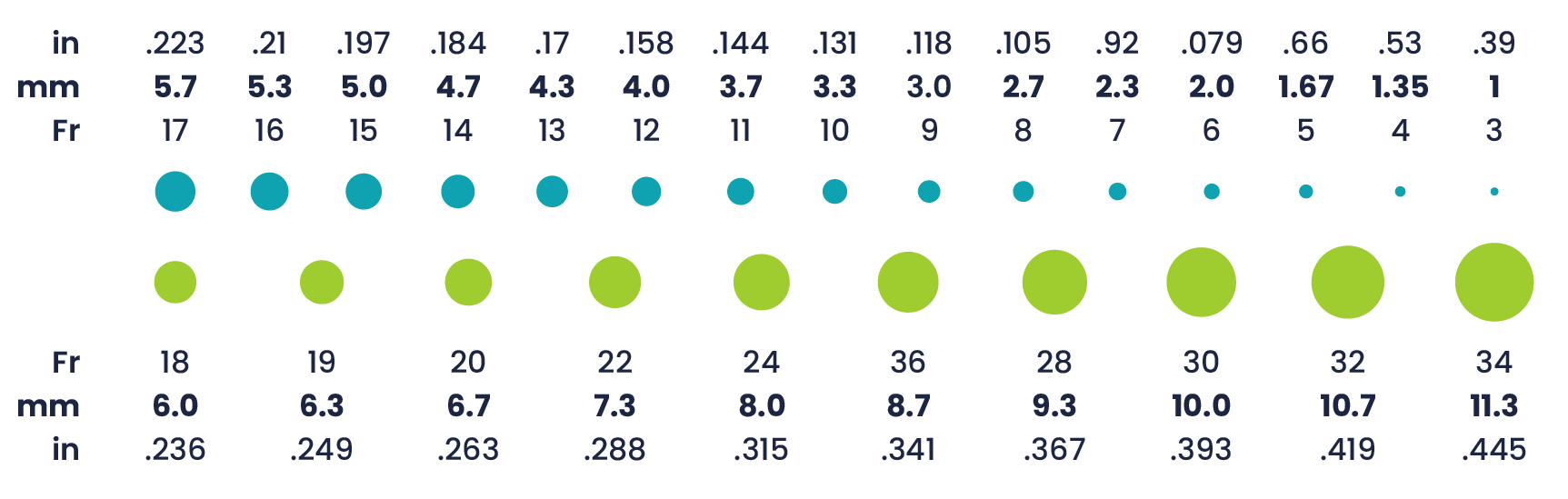

Catheters have different sizes, with the larger the number indicating a larger diameter of the catheter. See Figure 8 for an example of the French catheter scale.

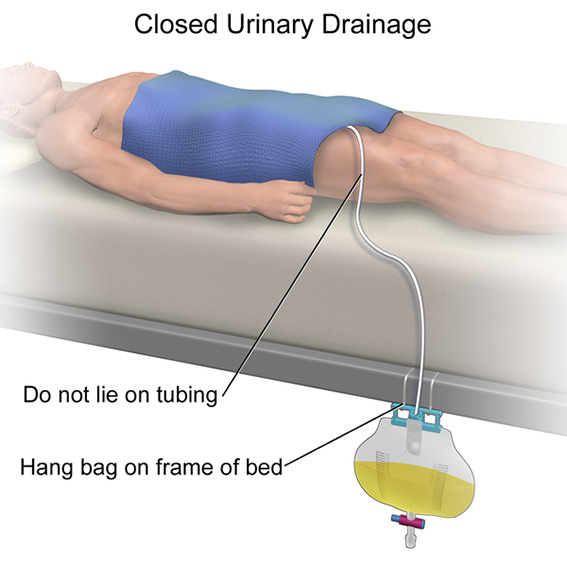

There are two common types of bags that may be attached to an indwelling catheter. During inpatient or long-term care, larger collection bags that can hold up to two litres of fluid are used. These bags should be emptied when they are half to two-thirds full to prevent traction on the urethra from the bag. When collecting urine, the collection bag should always be placed below the level of the patient’s bladder so that urine flows out of the bladder and urine does not inadvertently flow back into the bladder. The tubing should be checked regularly to ensure it is not coiled, kinked, or compressed, obstructing the flow of urine into the collection bag. The tubing from the bladder to the bag should not be pulled tight to ensure it remains in situ and does not injure the patient’s urethra. To prevent the development of a urinary tract infection, the bag should not touch the floor. See Figure 9 for an image of a typical collection bag attached to an indwelling catheter.

See Figure 10 for an illustration of the placement of the urine collection bag when the patient is lying in bed.

A second type of urine collection bag is a leg bag (Figure 11). A leg bag can provide discretion when the patient is in public because it can be worn under clothing. A leg bag is smaller and must be emptied more frequently to avoid overfilling.

Straight Catheter

A straight catheter (Figure 12) is used for intermittent urinary catheterisation. The catheter is inserted to allow for the flow of urine and then immediately removed, so a balloon is not required at the insertion tip. Intermittent catheterisation is used for the relief of urinary retention. It may be performed once, such as after surgery when a patient is experiencing urinary retention because of anaesthesia or performed several times a day to manage chronic urinary retention. Some patients may also independently perform self-catheterisation at home to manage chronic urinary retention caused by various medical conditions.

Irrigation Catheters

Irrigation catheters are typically used after prostate surgery to flush the surgical area. These catheters are larger to allow for irrigation of the bladder to help prevent the formation of blood clots and to flush them out.

Suprapubic Catheters

Suprapubic catheters are surgically inserted through the abdominal wall into the bladder. This type of catheter is typically inserted when there is a blockage within the urethra that does not allow the use of a straight or indwelling catheter. Suprapubic catheters may be used for a short period of time for acute medical conditions or may be used permanently for chronic conditions. See Figure 13 for an image of a suprapubic catheter. The insertion site of a suprapubic catheter must be cleaned regularly according to agency policy with appropriate steps to prevent skin breakdown.

Male Condom Catheter

A condom catheter is a noninvasive device used for males with incontinence. It is placed over the penis and connected to a drainage bag. This device protects and promotes healing of the skin around the perineal area and inner legs and is used as an alternative to an indwelling urinary catheter. See Figure 14 for an image of a condom catheter.

Collecting and Assessing Urine Quality

Analysing the characteristics of a urine sample is a crucial aspect of assessing and recognising cues for impaired urinary elimination. A diagnostic examination of a urine sample to assess various aspects of a person’s health is called urinalysis. This routine medical test provides valuable information about kidney function, hydration status, and the presence of underlying health conditions. Urine is collected in a number of ways depending on the patient’s condition. To collect a sample for urinalysis, patients can urinate into a urine specimen jar (see Figure 15) or urine can be collected aseptically from an indwelling catheter. The nurse will test the uncontaminated specimen by inserting a urine specimen stick, ensuring all indicators are covered, to examine the quality of the urine (Figure 16). The length of time required to complete the assessment and display accurate results depends on the type of urinalysis device used, and this information is generally displayed on the packaging. The examination assesses various aspects, including the physical properties of urine, such as colour, clarity, and odour, as well as chemical and microscopic elements such as pH levels, specific gravity, and the presence of proteins, glucose, blood cells, and crystals.

Normal urine should be clear, pale to light yellow in colour, and not foul-smelling. Alterations in the urine collected may indicate disease or acute illness, such as:

- Urine colour such as darker urine, can signal issues like dehydration, haematuria, or liver dysfunction.

- Urine clarity such as cloudy urine can signal conditions like urinary tract infections.

- Urine odour such as abnormal or foul smelling, can signal conditions like infections or metabolic disorders.

- Urine concentration such as changes in specific gravity can signal kidney impairment.

- Other changes such as urine sediment or crystals should be assessed as an additional step in pinpointing particular kidney disorders or impairments.

Measuring Fluid Balance

As urine is a part of the fluid being removed from the body, it needs to be calculated appropriately, especially for those with catheters to avoid potential fluid deficit. Not all catheters will require measurement of drainage, and this will depend on the clinical status of the patient. For those that do need measuring, fluid balance charts are the most common form of measurement tool used. Table 2 below shows the fluid balance chart commonly used in healthcare institutions (adapted from Walker, 2018).

| TIME | INPUT |

OUTPUT |

||||

| ORAL | IVT | URINE | VOMITUS | FAECES | DRAINS | |

| 0800 | ||||||

| 0900 | ||||||

| 1000 | ||||||

| 1100 | ||||||

| 1200 | ||||||

| 1300 | ||||||

| 1400 | ||||||

| 1500 | ||||||

| SUBTOTAL | ||||||

| 1600 | ||||||

Common Diseases and Disorders

Endocrine Disorders

These diseases can range in severity and include symptoms of urinary retention, decreased urinary output, and polyuria. Endocrine disorders include but are not limited to diabetes, polycystic ovary syndrome and hypothyroidism.

Renal Disorders

These include chronic kidney disease, acute kidney disease and nephrotic syndrome, all of which can affect the production, filtering and composition of urine. Symptoms can include high blood pressure, changes in the appearance of the urine, changes in the amount voided, puffiness in the legs or ankles and pain in the kidney area.

Cancers

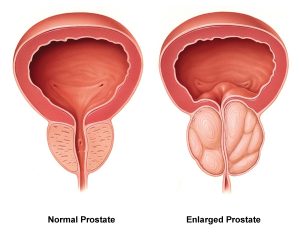

There are many different cancers that can affect the function of the genitourinary system, including bladder cancer, renal cell carcinoma, testicular cancer, penile cancer and urethral cancer. One of the most common kinds of cancers that can affect the urinary system is prostate cancer. This disease involves a mutation in prostate cells resulting in overproduction of cancerous cells. Depending on the stage of the cancer, symptoms include hematuria, increased urinary frequency and nocturia.

Common Complications

Urinary Tract Infection

Infections can affect several parts of the urinary tract, but the most common type is a bladder infection (cystitis). Kidney infections (pyelonephritis) are more serious than bladder infections because they can have long-lasting effects on the kidneys.

Some people are at higher risk of developing a UTI. UTIs are more common in females because their urethras are shorter and closer to the rectum, which makes it easier for bacteria to enter the urinary tract. Other factors that can increase the risk of UTIs include the following:

- A previous UTI

- Sexual activity, especially with a new sexual partner

- Pregnancy

- Age

- Structural problems in the urinary tract, such as prostate enlargement.

Symptoms of a UTI include the following:

Symptoms of a more serious kidney infection (pyelonephritis) include fever above 38.3 degrees C (101 degrees F), shaking chills, lower back pain or flank pain (i.e., on the sides of the back), and nausea or vomiting. It is important to remember that older adults with a UTI may not exhibit these symptoms but often demonstrate an increased level of confusion. Sometimes UTIs can spread to the blood (septicaemia), leading to a life-threatening infection called sepsis.

When a patient presents with symptoms of a UTI, the medical team will order diagnostic tests, such as a urinalysis, or urine culture.

|

Interventions Antibiotics are prescribed for urinary tract infections. Nurses provide important health teaching to patients with a UTI, such as the importance of finishing their antibiotic therapy as prescribed, even if they begin to feel better after a few days, to minimise the risk of developing antibiotic-resistant microorganisms. Patients should also be encouraged to drink extra fluids to help flush bacteria from the urinary tract. Additional health teaching regarding preventing future UTIs includes the following:

|

Urinary Retention

Urinary retention can be acute (i.e., the sudden inability to urinate after receiving anaesthesia during surgery) or chronic (i.e., a gradual inability to completely empty the bladder due to enlargement of the prostate gland in males). Urinary retention is caused by a blockage that partially or fully prevents the flow of urine or the bladder not being able to create a strong enough force to expel all the urine. In addition to causing discomfort, urinary retention increases the patient’s risk for developing a urinary tract infection because bacteria from the urethra can move up toward the bladder and multiply in retained urine. See Figure 17 for an image of an enlarged prostate gland blocking the flow of urine from the bladder into the urethra.

|

Interventions Symptoms of urinary retention can range from none to severe abdominal pain. Healthcare providers use a patient’s medical history, physical assessment, and diagnostic tests to find the cause of urinary retention. Nurses typically receive orders to measure post-void residual amounts when urinary retention is suspected. These measurements are taken after a patient has voided by using a bladder scanner or inserting a straight urinary catheter to determine how much urine is left in the bladder.

|

Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infection

A catheter-associated urinary tract infection (CAUTI) is a common, life-threatening complication caused by indwelling urinary catheters. The development of a CAUTI is associated with patients’ increased length of stay in the hospital, resulting in additional hospital costs and a higher risk of death. Catheter-associated UTIs are the most prevalent of all hospital-acquired UTIs in Australia, accounting for 80% of hospital-acquired UTIs (Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care, 2018). The main risk factor for a CAUTI is unnecessary catheterisation. However, CAUTIs are the most preventable types of UTIs. The duration of catheterisation and the place where the catheter was inserted in the hospital, as well as gender (female) and other comorbidities (diabetes), also may increase a patient’s risk of acquiring a CAUTI during their hospital stay. For a CAUTI to occur, microorganisms need to enter the catheter system either externally (contamination of the catheter at the time of insertion by microflora and other organisms from the perineal region) or internally (contamination caused by the manipulation of the catheter or drainage system post insertion).

Key strategies to prevent CAUTIs include:

- Insert catheters only for clinically appropriate indications under aseptic technique.

- Select the most appropriate catheter for the patient in terms of size, length, material and drainage system.

- Ensure that catheter insertion is done only by clinicians who have demonstrated competence in aseptic technique and catheter insertion.

- Clearly document the indication for the catheter insertion, review or removal time, and details of the insertion (person responsible for inserting the catheter, date and time of insertion and the gauge of the catheter used).

- Following catheter insertion:

- Ensure the catheter is secured to the patient at all times

- Maintain a closed drainage system and unobstructed urine flow (that is, no kinking, no backflow, drainage bag should not be more than ¾ full at any time)

- Only handle catheters and the drainage system using aseptic technique and use the sampling port to collect samples if required

- Ensure that the insertion site and peri-urethral area are cleaned and checked daily.

- Leave the catheters in place only for as long as needed and review the need for catheterisation regularly (daily).

- Use portable ultrasound devices to assess urine volumes.

- Adopting quality-improvement practices to reduce the incidences of CAUTI.

- Protocols for nurse-directed removal of unnecessary catheters.

Practices that are not recommended:

- Changing urethral catheters at routine, fixed intervals (clinical indications include infection, obstruction, or compromise of the closed system)

- Routine antimicrobial prophylaxis for catheter insertion

- Bladder irrigation with antimicrobials

- Routine screening for asymptomatic bacteriuria.

Urinary Incontinence

Although abnormal, urinary incontinence is a common symptom that can seriously affect the physical, psychological, and social well-being of individuals of all ages. Some believe it’s a normal part of ageing and that they have to live with it. The result can be isolation and depression when they limit their activities and social interactions because of embarrassment due to incontinence. Nurses can greatly improve the quality of life for these patients by assessing for urinary incontinence in a sensitive manner and then providing health teaching about methods to prevent and/or manage incontinence.

Types of Urinary Incontinence

Continence is achieved through an interplay of the physiology of the bladder, urethra, sphincter, pelvic floor, and the nervous system coordinating these organs. A disruption in any of these areas can cause several types of urinary incontinence:

It is important for nurses to understand the different types of incontinence so that appropriate interventions can be targeted to the cause.

Assessment of Incontinence

- Screening questions such as pain or problems experienced before, during or after urinating

- Ascertaining when and how much the patient urinates

- Urinary leakage and what the patient was doing when it happened (for example, running, biking, laughing)

- Sudden urges to urinate

- How often the patient wakes at night to use the bathroom

- Type and volume of food and beverages, and the time of intake

- Medication use, such as diuretics, and the timing of administration.

Treatment of Incontinence

|

Nurses should use therapeutic communication with patients experiencing urinary incontinence to help them feel comfortable in expressing their fears, worries, and embarrassment about incontinence and work toward improving their quality of life. Patient education should include information about pelvic floor muscle training exercises, timed voiding, lifestyle modification, and incontinence products.

|

Nurses play an important role in educating patients about bladder control training to prevent incontinence. Bladder control training includes several techniques:

- Pelvic muscle exercises (also known as Kegel exercises) work the muscles used to stop urination, which can help prevent stress incontinence.

- Timed voiding can be used to help a patient regain control of the bladder. Timed voiding encourages the patient to urinate on a set schedule, for example, every hour, whether they feel the urge to urinate or not. The time between bathroom trips is gradually extended with the general goal of achieving four hours between voiding. Timed voiding helps to control urge and overflow incontinence as the brain is trained to be less sensitive to the sensation of the bladder walls expanding as they fill.

- Lifestyle changes can help with incontinence. Losing weight, drinking less caffeine (found in coffee, tea, and many sodas), preventing constipation, and avoiding lifting heavy objects may help with incontinence. Limiting fluid intake before bedtime and scheduling prescribed diuretic medication in the morning or early afternoon are also helpful.

- Protective products may be needed to protect the skin from breakdown and prevent leakage onto clothing. Incontinence underwear has a waterproof liner and built-in cloth pad to absorb large amounts of urine to protect skin from moisture and control odour.

- If bladder training and medications are not effective, surgery may be performed, such as a sling procedure or a bladder neck suspension.

Gastrointestinal System

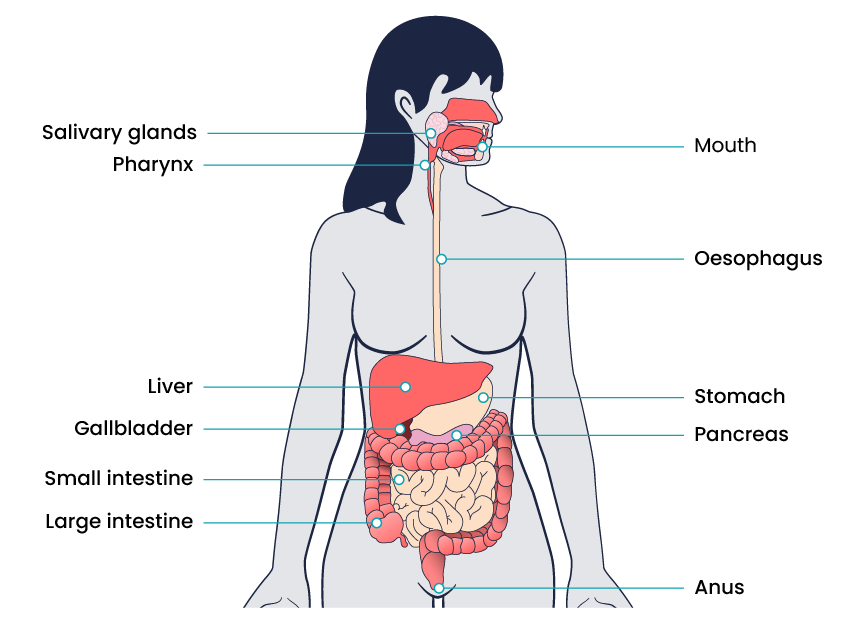

The gastrointestinal (GI) system includes the mouth, oesophagus, stomach, small intestine, large intestine, and anus. Ingested food and liquid are pushed through the GI tract by peristalsis, the involuntary contraction and relaxation of muscle creating wave-like movements of the intestines. The stomach and small intestine mix food and liquid with digestive enzymes to digest food. The walls of the small intestine absorb water and the digested nutrients into the bloodstream. As peristalsis continues, the waste products of the digestive process move into the large intestine. The large intestine absorbs water and changes the waste into stool. The rectum, at the lower end of the large intestine, stores stool until it is pushed out of the anus during a bowel movement. See Figure 18 for a complete picture of the gastrointestinal system.

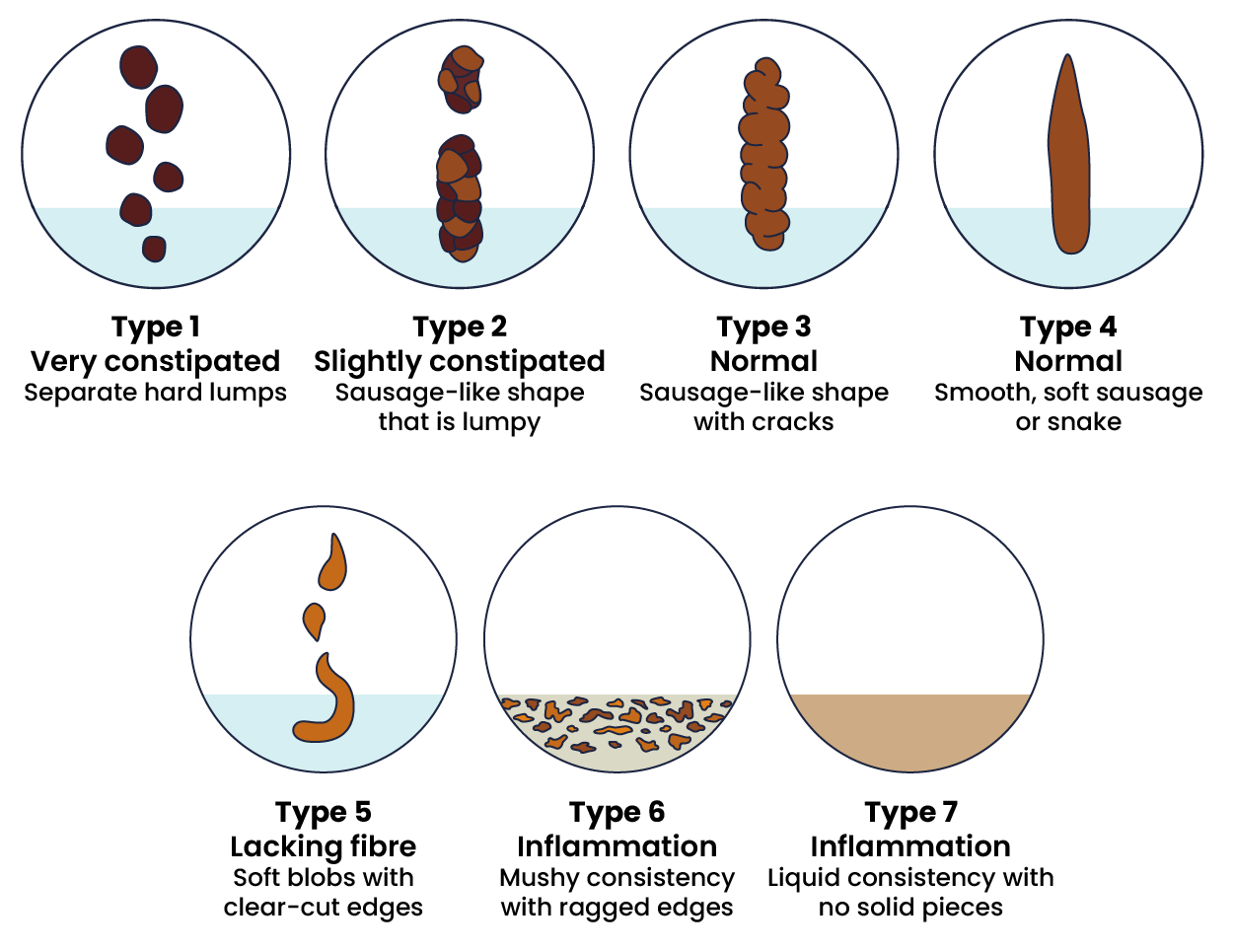

Documenting Output

Gastrointestinal waste can vary depending on different factors, including dietary intake, age, acute or chronic illness or disease and lifestyle factors such as exercise. A Bristol Stool Chart is commonly used to communicate or document the consistency of waste in the healthcare setting. See Figure 19 for the Bristol Stool Chart used to assess the characteristics of stools, ranging from constipation to diarrhoea. Normal bowel function should include faecal output between the level of type 3 and type 4.

Common Complications

Constipation

A patient is usually diagnosed with constipation if they have less than three bowel movements per week. Constipation can be caused by slowed peristalsis due to decreased activity, dehydration, lack of fibre, medications such as opioids, or surgical procedures in the abdominal area. As the stool moves slowly through the large intestine, additional water is reabsorbed, resulting in the stool becoming hard, dry, and difficult to move through the lower intestines.

Faecal impaction occurs when hardened faecal matter is unable to be evacuated with regular peristalsis activity and is retained in the rectum. The patient may experience symptoms such as rectal pressure, abdominal cramps, bloating, distension, and straining. A patient with faecal impaction often will experience liquid loss, which can result in a misdiagnosis of diarrhoea. The compacted stool must be removed to maintain the health of the colon (Setya et al., 2023). If prolonged faecal impaction is experienced, the patient may suffer from bowel obstruction, bowel perforation, peritonitis, ulcers or dehydration.

|

Treatment The goal when treating constipation is to establish what is considered a normal bowel pattern for each person and to set an expected outcome of a bowel movement at least every 72 hours, regardless of intake. Treatment typically includes a prescribed daily bowel regimen, such as oral stool softeners and a mild stimulant laxative. Stronger laxatives, rectal suppositories, or enemas are implemented when oral medications are not effective. When treating severe faecal impaction, manual disimpaction may be needed, requiring a qualified healthcare practitioner to manually remove impacted stool. Patients should be educated about the importance of adequate fluid intake, dietary requirements and remaining active to prevent constipation.

|

Intestinal Obstruction or Paralytic Ileus

Intestinal Obstruction

Intestinal obstruction is a partial or complete blockage of the intestines so that the contents of the intestine cannot pass through it. Intestinal obstruction can be caused by adhesions, hernias, tumours, volvulus, intussusception and certain inflammatory conditions, such as diverticulitis. When the intestinal tract becomes blocked or obstructed, the bowel tissue can become ischaemic, causing that section of the bowel to become necrotic and need removal. The symptoms of a bowel obstruction include:

- Abdominal pain or cramping

- Bloating or distention (swollen abdomen)

- Nausea and vomiting

- Inability to pass stool or gas

- Constipation

- Diarrhoea.

If a patient is suspected of suffering from a bowel obstruction, they must undergo a physical examination, imaging tests and a blood test to look for signs of occlusion, dehydration and bowel sounds.

A bowel obstruction can lead to serious complications if not treated promptly, including:

- Dehydration and electrolyte imbalances

- Infection

- Perforation

- Ischemia

- Sepsis.

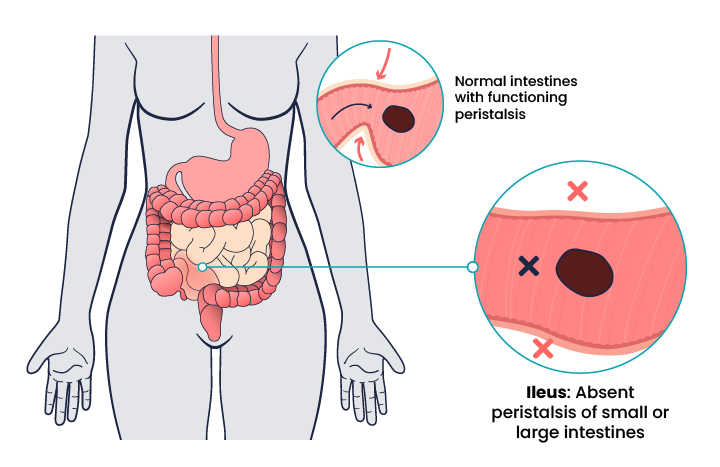

Paralytic Ileus

Other types of obstruction or disruption to normal functioning can be caused by paralytic ileus, a condition where peristalsis is not moving the contents through the intestines. Patients who have undergone abdominal surgery or received general anaesthesia are at increased risk for paralytic ileus. Other risk factors include the chronic use of opioids, electrolyte imbalances, bacterial or viral infections of the intestines, decreased blood flow to the intestines, or kidney or liver disease. If an obstruction blocks the blood supply to the intestine, it can cause infection and tissue death.

Symptoms of a paralytic ileus include:

- Abdominal distention or bloating

- Abdominal pain or cramping

- Inability to pass gas

- Nausea and vomiting

- Constipation or diarrhoea

- Absence of bowel sounds.

Bowel sounds must be assessed for abnormal findings. It can be difficult to accurately interpret changes in bowel sounds, so any change in bowel sounds accompanied by other symptoms should be reported to the health care provider. Absent bowel sounds can indicate an ileus or mechanical bowel obstruction. Paralytic ileus is generally a temporary condition experienced by postoperative patients, and commonly dietary restrictions are not lifted until a postoperative patient passes wind.

|

Treatment Treatment includes maintaining strict NBM (nil by mouth) status and typically includes insertion of a naso-gastric (NG) tube attached to suction to help relieve abdominal distention and vomiting until peristalsis returns. Patients suffering from an ileus will generally have intravenous fluids, medications to stimulate peristalsis and regular and early mobilisation.

|

Diarrhoea

Diarrhoea is defined as having more than three unformed stools in 24 hours. Diarrhoea is caused by increased peristalsis, causing the stool to move too quickly through the large intestines so that water is not effectively reabsorbed, resulting in loose, watery stools. It can cause dehydration, skin breakdown, and electrolyte imbalances. Many conditions can cause diarrhoea, such as bacterial or viral infections, food poisoning, medications, food intolerances, allergies, anxiety, and medical conditions like irritable bowel disease and Crohn’s disease.

|

Treatment Treatment of diarrhoea includes promoting hydration with fluids that improve electrolyte status. Intravenous fluids may be required if the patient becomes dehydrated. Medications such as loperamide, psyllium, and anticholinergic agents may be prescribed to treat diarrhoea causing dehydration.

|

Bowel Incontinence

Bowel incontinence is the accidental loss of bowel control causing the unexpected passage of stool. Incontinence can range from leaking a small amount of stool or gas to not being able to control bowel movements. The rectum, anus, pelvic muscles, and nervous system must work together to control bowel movements.

Causes of bowel incontinence include the following:

- Ongoing (chronic) constipation, causing the anus muscles and intestines to stretch and weaken, leading to diarrhoea and stool leakage

- Faecal impaction with a lump of hard stool that partly blocks the large intestine

- Long-term laxative use

- Colectomy or bowel surgery

- Lack of sensation of the need to have a bowel movement

- Gynecological, prostate, or rectal surgery

- Injury to the anal muscles in women due to childbirth

- Nerve or muscle damage from injury, a tumour, or radiation

- Severe diarrhoea that causes leakage

- Severe haemorrhoids or rectal prolapse

- Stress of being in an unfamiliar environment

- Emotional or mental health issues.

|

Treatment Many people feel embarrassed about bowel incontinence and do not share this information with their healthcare provider. It is essential for nurses to communicate therapeutically with patients experiencing bowel incontinence and let them know it can often be treated with simple interventions such as diet changes, bowel retraining, pelvic floor exercises, or referral for surgical review if indicated. Ask the patient to track the foods eaten to determine if certain types of foods cause problems. Foods that may lead to incontinence in some people include the following:

Bowel retraining involves teaching the body to have a bowel movement at a certain time of the day. This also includes encouraging the patient to go to the bathroom when feeling the urge to do so and not ignoring it. Encourage patients with bowel incontinence to use special pads or undergarments to help them feel protected from accidents when they leave home. These products are available in pharmacies and in many other stores.

|

Cultural Considerations

|

When dealing with patients and their elimination needs there are cultural considerations that need to be identified by the nurse. Such considerations include cultural taboos surrounding discussing body function, disparities in healthcare access, gender sensitivity, alternative medication practices, family involvement and dietary and lifestyle practices. Procedures such as catheter insertion, stoma care and insertion of suppositories can cause emotional distress, especially if the patient has experienced any history of abuse or trauma.

|

Ostomies

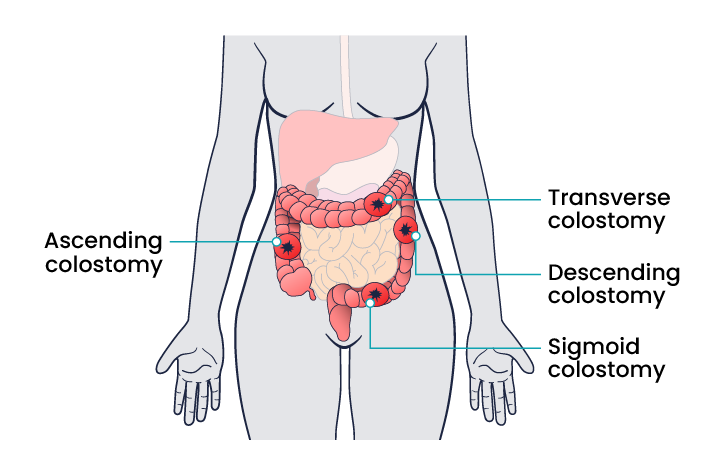

An ostomy is a surgical procedure that creates an opening (stoma) from an area inside the body to the outside of the body. In ostomies related to elimination, a stoma is an opening on the abdomen that is connected to the gastrointestinal or urinary system to allow waste (i.e., urine or faeces) to be collected in a pouch. There are several different kinds of ostomies related to elimination. It is important for the nurse to understand the site of a patient’s ostomy because the location will impact the characteristics of the waste excreted. For example, due to the natural digestive process of the colon and absorption of water, waste from an ileostomy or a colostomy placed in the anterior ascending colon will be watery compared to waste from an ostomy placed in the descending colon. A stoma can be permanent, such as when an organ is removed, or temporary, such as when an organ requires time to heal. Ostomies are created for patients with conditions such as cancer of the bowel or bladder, inflammatory bowel diseases, or perforation of the colon.

Appearance

The tissue of a stoma is very delicate. Immediately after surgery, a stoma is swollen, but it will shrink in size over several weeks. A healthy, healed stoma appears moist and dark red or pink in colour. Stomas that are swollen; dry; have malodorous discharge; or are bluish, purple, black, or pale should be reported to the provider.

The skin surrounding a stoma can easily become irritated from the pouch adhesive or leakage of fluid from the stoma, so the nurse must perform interventions to prevent skin breakdown. Any identified signs of skin breakdown should be reported to the provider. If the surrounding skin becomes excoriated, securing the appliance to the stoma will become difficult and often result in further leakage.

Individuals with colostomies, ileostomies, and urostomies have no sensation and no control over the output of the stoma. Depending on the type of system, the ostomy appliance can last from four to seven days, but the pouch must be changed if there is leaking, odour, excessive skin exposure, or itching or burning under the skin barrier. Patients with pouches can swim and take showers with the pouching system on.

Colostomy

A colostomy is an ostomy formed in the large intestine, designed to bypass the rectum and/or anus. As a colostomy is located towards the end of the gastrointestinal tract, the waste excreted from a colostomy usually is a similar consistency to that of a formed stool. A colostomy can be permanent or temporary and is generally formed as a result of:

- A birth defect

- Diverticulitis

- Inflammatory bowel disease

- Injury to the colon or rectum

- Cancer

- Partial or complete intestinal blockage

- Wound or fistula.

Depending on the medical reason for the colostomy and if it is temporary or permanent, there are several different sites the stoma can be formed. See Figure 21 for the different sites where a colostomy can be formed.

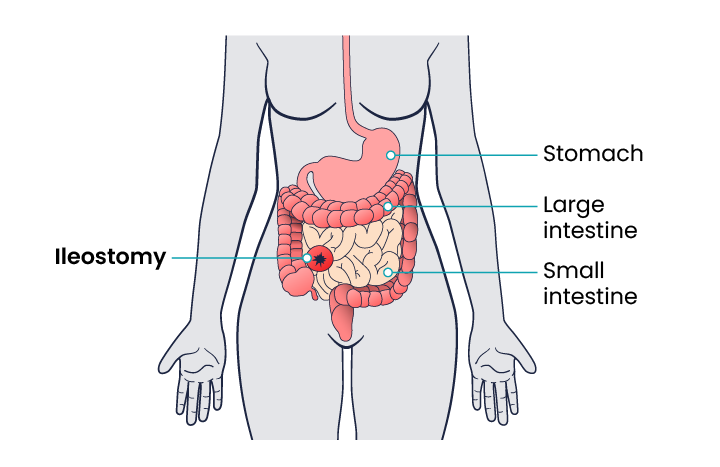

Ileostomy

An ileostomy is an ostomy formed in the small intestine, designed to bypass the colon and rectum. As an ileostomy is located at the beginning of the intestinal tract, the waste excreted from an ileostomy is usually thin and water-like in appearance. An ileostomy can be temporary or permanent and is generally formed as a result of:

- Congenital condition

- Crohn’s disease

- Cancer

- Ulcerative colitis

- Trauma, injury or perforation of the bowel

- Diverticulitis.

An ileostomy is generally formed on the right-hand side of the abdomen with the lower end of the small intestine (ileum) attached to a stoma to bypass the colon, rectum, and anus.

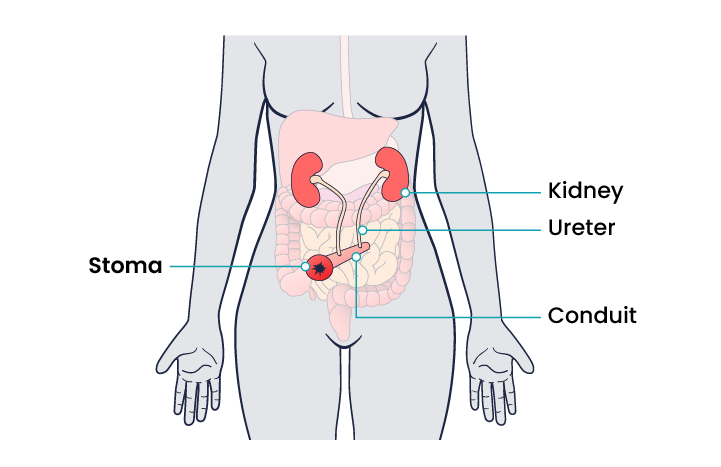

Urostomy

A urostomy is an ostomy formed as another way for someone to excrete urine. When forming a urostomy, the ureters (tubes that carry urine from the kidney to the bladder) are attached to a stoma to bypass the bladder. A urostomy patient has no voluntary control of urine, so the pouching system must be emptied regularly. The pouch may also be attached to a drainage bag for overnight drainage. Patients with a urostomy are at risk for urinary tract infections (UTIs), so it is important to educate them regarding the signs and symptoms of an infection. A urostomy is usually formed as a result of:

- Chronic, long-term incontinence

- Congenital defects

- Spinal cord injuries

- Cancer

- Damaged urethras.

There are different types of urostomies that can be formed by a surgeon, including ileal conduit, colonic conduit or a continent urostomy.

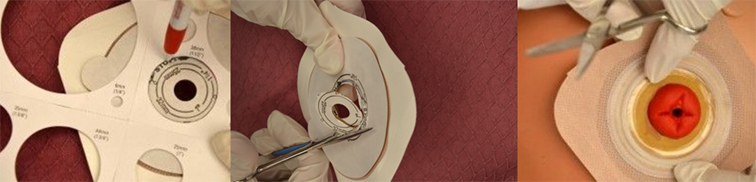

Stoma Appliance

Stoma appliances are supplied as a one or two-piece set. A two-piece set consists of an ostomy barrier (also called a wafer) and a pouch. The ostomy barrier is the part of the appliance that sticks to the skin with a hole that is fitted around the stoma. The pouch collects the waste and must be emptied regularly. The pouching system must be completely sealed to prevent leaking of the waste and to protect the surrounding peristomal skin. The pouch has an end with an opening where the waste can be emptied and is closed using a plastic clip or seal. In the one-piece stoma appliance set, the ostomy barrier and the pouch are one piece. See Figure 24 for an image of a stoma with an ostomy barrier in place. See Figure 25 for an image of a patient with an ileostomy appliance with a pouch attached.

When changing an ostomy appliance, the ostomy barrier is cut to fit closely around the stoma without impinging on it. The nurse measures the stoma with a template and then cuts and fits the ostomy barrier to a size that is 2 mm larger than the stoma. See Figure 26 for an image of a nurse measuring and cutting the ostomy barrier to fit around a stoma.

After the skin barrier is applied to the skin, the pouch is snapped to the barrier. See Figure 27 for an image of applying the pouch.

Physical and Emotional Assessment

Patients may have other medical conditions that affect their ability to manage their ostomy care. Conditions such as arthritis, vision changes, Parkinson’s disease, or post-stroke complications can hinder a patient’s coordination and ability to manage the ostomy. In addition, the emotional burden of coping with an ostomy may be devastating for some patients and may affect their self-esteem, body image, quality of life, and ability to be intimate. It is common for patients with ostomies to struggle with body image and their altered pattern of elimination.

Nurses can promote healthy coping by ensuring the patient has appropriate referrals to a wound/ostomy nurse specialist, a social worker, and support groups. Nurses should also be aware of their nonverbal cues when assisting a patient with their appliance changes. It is vital not to show signs of disgust at the appearance of the ostomy or at the odour that may be present when changing an appliance or pouching system.

Key Takeaways

In this chapter, we covered:

- Elimination is a basic human function of excreting waste through the urinary and bowel systems. This process can differ between individuals due to a range of intricate variables such as medical conditions, diet and exercise, and surgical procedures.

- The urinary system is often referred to as the renal system and consists of the kidneys, ureters, bladder and urethra. Its purpose is to eliminate urine from the body, regulate blood volume and pressure, control levels of electrolytes and metabolites, and regulate blood pH.

- There are many devices used to facilitate urinary elimination, and most catheter appliances use a tube to drain the urine from the bladder and deposit it into a drainage or collection bag.

- Many complications or disorders can disrupt elimination from the urinary system, including renal disorders, cancer, urinary tract infections, and catheter-associated urinary tract infections.

- The gastrointestinal system includes the mouth, oesophagus, stomach, small intestine, large intestine, and anus and is responsible for involuntarily moving food and liquid by peristalsis through the gastrointestinal tract.

- Many complications or disorders can disrupt elimination from the gastrointestinal system, including constipation, cancer, paralytic ileus, and diarrhoea.

- An ostomy is a surgical procedure that creates an opening (stoma) from an area inside the body to the outside of the body to excrete waste.

- There are several different types of ostomies, including ileostomy, colostomy and urostomy, and the location of the ostomy generally determines the type of stoma.

References

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. (n.d.). Hospital-acquired complication 3: Healthcare-associated infections. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/sites/default/files/migrated/SAQ7730_HAC_Factsheet_HealthcareAssociatedInfections_LongV2.pdf

Kidney Health Australia (2020). Symptoms of kidney disease. kidney.org.au/your-kidneys/what-is-kidney-disease/symptoms-of-kidney-disease

Setya A., Mathew G., & Cagir B. (2023). Fecal impaction. In W. B. Ackley, T. S. Adolphe, T. C. Aeby, N. R. Aeddula, S. Agadi, P. Agasthi, S. Ahmad, A. Ahmed, F. W. Ahmed, I. Ahmed, R. A. Ahmed, S. W. Ahmed, A. M. Akanmode, R. Akella, S. M. Akram, Y. Al Khalili, E. Al Zaabi, M. H. Alahmadi, G. Alexander, … H. Zulfiqar (Eds). StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved December 10, 2024 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448094/

Walker, S. (2018). Fluid, electrolyte and acid-base balance. In Berman, A., Snyder, S., Levett-Jones, T., Dwyer, T., Hales, M., Harvey, N., Langtree, T., Moxham, L., Parker, B., Reid-Searl, K., & Stanley, D. (Eds), Kozier and Erb’s fundamentals of nursing: Concepts, process and practice (Vol 3, 4th ed.) Pearson.

Chapter Attribution

This chapter has been adapted in parts from:

Fundamentals of Nursing (2024) by C. Bowen, L. Draper and H. Moore, OpenStax is used under a CC BY licence.

Medical-Surgical Nursing (2024) by C. Bowen, B. Carey, J. Palozie and M. Reinholdt, OpenStax, is used under a CC BY licence.

Nursing Fundamentals 2e (n.d.) by Open Resources for Nursing, Chippewa Valley Technical College is used under a CC BY licence.

Nursing Skills 2e (2023) by Open Resources for Nursing, Chippewa Valley Technical College is used under a CC BY licence.

Media Attributions

- Female Urinary System © J. Gordon Betts, Kelly A. Young, James A. Wise, Eddie Johnson, Brandon Poe, Dean H. Kruse, Oksana Korol, Jody E. Johnson, Mark Womble & Peter DeSaix adapted by Eileen Siddins is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Male Urinary System © J. Gordon Betts, Kelly A. Young, James A. Wise, Eddie Johnson, Brandon Poe, Dean H. Kruse, Oksana Korol, Jody E. Johnson, Mark Womble & Peter DeSaix adapted by Eileen Siddins is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Bed Pan © Sandra Dash is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Commode Chair © Sandra Dash is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Urinal Bottle © Sandra Dash is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Indwelling Catheter © Eileen Siddins is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Parts of Indwelling Catheter © Olek Remesz is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- French Cather Scale Sizes © Glitzy queen00 adapted by Eileen Siddins is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Urine Collection Bag © Ben Green is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Closed Urinary Drainage © BruceBlaus is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Catheter Bag Attached to Leg © BruceBlaus is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Female straight catheter © Leisa Sanderson is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- NewlyPlaceSubprapubic © James Heilman is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Condom Catheter © BruceBlaus is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Urine Specimen Jar © Sandra Dash is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Urine Specimen Sticks © Sandra Dash is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Normal vs Enlarged Prostate © Akcmdu9 is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Gastrointestinal System © Eileen Siddins is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Bristol Stool Chart © Cabot Health adapted by Eileen Siddins is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Absent peristalsis © Eileen Siddins is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Colostomy © Eileen Siddins is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Ileostomy © Eileen Siddins is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Urostomy © Eileen Siddins is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Ostomy Wafer © Eric Polsinelli (VeganOstomy) is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Ileostomy Pouch © Salicyna is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Fitting Barrier to Stoma © Glynda Rees Doyle & Jodie Anita McCutcheon adapted by Ernstmeyer & Christman (Eds.) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Applying Ostomy Bag From Flange © Glynda Rees Doyle & Jodie Anita McCutcheon is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

A urinary tract infection (UTI) is a common infection that occurs when bacteria, typically from the rectum, enter the urethra and infect the urinary tract

A condition when the client cannot empty all of the urine from their bladder

Greater than 2.5 liters of urine output over 24 hours, also referred to as diuresis. Urine is typically clear with no colour. New polyuria should be reported to the health care provider because it can be a sign of many medical conditions

Blood in the urine, either visualized or found during microscopic analysis

The need to urinate several times during the day or at night (nocturia) in normal or less-than-normal volumes. It may be accompanied by a feeling of urgency

The need to get up at night on a regular basis to urinate. Nocturia often causes sleep deprivation that affects a person’s quality of life

Painful or difficult urination

A sensation of an urgent need to void. Urgency can cause urge incontinence if the client is not able to reach the bathroom quickly

The involuntary loss of urine

Defined as less than three stools per week, caused by decreased peristalsis due to limited physical activity, dehydration, dietary changes, medications or surgical procedures

Hardened faecal matter is unable to be evacuated with regular peristalsis activity and is retained in the rectum

Fibrous bands of tissue that can form after surgery, potentially constricting the intestines

Occur when a part of the intestine bulges through a weak area in the abdominal wall, potentially getting pinched and causing a blockage

Growths, both benign and cancerous, can obstruct the intestines either from within or by pressing on them from outside

A twisting of the intestine around its blood supply, leading to a blockage

A section of the intestine telescopes into the adjacent section, causing a blockage

Inflammation or infection of the small pouches in the colon

The accidental loss of bowel control causing the unexpected passage of stool

Teaching the body to have a bowel movement at a certain time of the day

A surgical procedure that creates an opening (stoma) from an area inside the body to the outside of the body

The lower end of the small intestine (ileum) is attached to a stoma to bypass the colon, rectum, and anus