Assessing and Supporting Hygiene

Amy McCrystal; Tracey Gooding; and Jessica Best

Learning Outcomes

In this chapter, you will learn how to:

- Explain the rationale for assisting individuals with personal hygiene, emphasising its role in maintaining health and preventing infections

- Identify the various factors that influence personal hygiene practices, including cultural, developmental, and individual preferences

- Demonstrate the methods and techniques nurses use to provide hygiene assistance, ensuring patient comfort, safety, and dignity

- Evaluate key considerations when assessing and assisting patients with hygiene care, tailored to their specific needs and developmental stages.

Introduction

Personal hygiene is a fundamental aspect of healthcare that plays a crucial role in maintaining overall health and preventing infections. Assisting individuals with personal hygiene is not only about cleanliness but also about promoting well-being and dignity. This chapter aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of the importance of personal hygiene and the various factors that influence hygiene practices. This chapter explores the importance of hygiene care, factors influencing practices (such as culture, development, and patient goals and preferences), and fundamental nursing techniques to assist in hygiene care while highlighting how to tailor care to individual needs, ensuring safe, respectful, and effective hygiene assistance.

Hygiene

Hygiene refers to the practices that promote health and prevent disease through cleanliness. When individuals perform these practices to maintain their own well-being, it is known as personal hygiene, which is an essential component of Activities of Daily Living (ADL). This includes tasks such as bathing, oral care, toileting, grooming, shaving and hair care (Cremer et al., 2023). Although these may seem basic, they are vital for preserving health.

Various factors, including ageing, socio-economic conditions, and illness, can impact a person’s ability to maintain personal hygiene independently (Cremer et al., 2023; Somrongthong, 2017). In a hospital setting, patients often experience functional decline due to illness and reduced physical activity (Verstraten et al., 2020). Nurses play a crucial role in supporting patients’ self-care by promoting mobility, preserving dignity, and maintaining autonomy (Cremer et al., 2023; Verstraten et al., 2020). Assisting with hygiene also allows nurses to assess a patient’s ability to perform ADLs during recovery and prepare them for discharge.

While some patients require minimal support, others may be fully dependent on nurses for essential tasks such as bathing, elimination, bed-making, and oral care. The type of care provided depends on the perceived level of dependence and care goals, such as maintaining functional status or ensuring comfort (Cremer et al., 2023; Goldenhart & Nagy, 2022). In providing this care, nurses must respect patient preferences, ensure privacy, and consider both physical and emotional well-being. By doing so, they help maintain patient dignity and enhance overall quality of life.

Assessing Personal Hygiene

Good hygiene can not only protect an individual from becoming ill, it can help to prevent hospital-associated infections (HAIs) and prevent individuals from spreading infection to others (Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care [ACSQHC], 2021). Good hygiene also promotes self-esteem and can boost a patient’s mood, resulting in improved mental health (Goldenhart & Nagy, 2022). Assessing hygiene involves evaluating multiple areas of the body to ensure overall health and well-being. Key considerations include the condition of the skin, hair, nails, oral cavity, and perineum.

Skin

The skin is the largest organ and the body’s first line of defence. This organ provides a barrier to protect the body from invasion of bacteria or other potential environmental hazards and is integral to physical and psychosocial health (Mitchell, 2022). The skin houses various functional body structures, such as capillaries, vessels, and glands. For example, the dermis layer of the skin contains sebaceous glands. These glands release sebum, an oily secretion that hydrates and protects the skin. It is important to note this glandular function, as inadequate hygiene may lead to excess sebum and skin breakouts. As skin ages, it becomes more prone to dryness, itching, cracks, and tears. These issues are common among older adults, impacting their quality of life and increasing the risk of skin breakdown. This can lead to greater dependency, prolonged hospital stays, and higher financial and caregiving burdens (Bonifant & Holloway, 2019; Cowdell et al., 2023).

Proper hygiene practices can help promote and maintain skin integrity and allow the skin to properly perform the functions of protection, sensation, heat regulation, excretion, secretion, and absorption (Mitchell, 2022). In addition, the regular practice of skin hygiene allows for early detection and intervention of abnormal skin conditions such as incontinence-associated dermatitis (IAD), skin tears or pressure injuries (ACSQHC, 2020; Cowdell, 2023; McNichol et al., 2021). Skin breakdown refers to damage or injury to the skin and underlying tissue due to prolonged pressure, friction, shear, or moisture. Examples of skin breakdown include burns, scrapes, cuts, blisters, incontinence-associated dermatitis (Figure 2) and pressure injuries. Factors associated with skin breakdown include immobility, certain medications, incontinence, altered mental status, loss of sensation, or inadequate nutrition (ACSHQHC, 2020).

In a hospital setting, regular and thorough documentation of skin assessments is vital, as it establishes a baseline for each patient’s skin condition, facilitates early detection of changes, and guides appropriate interventions to prevent complications. Often, the best time to do a thorough skin assessment is during hygiene care. Additionally, skin hygiene practices are critical in patients at increased risk of skin breakdown or injury such as those with diabetes, circulatory insufficiency, increased body temperature and a lack of nutrition (ACSQHC, 2020). Comprehensive skin assessments should be conducted upon admission, daily, and during any transitions in care, with frequency adjusted based on individual risk factors and clinical settings (Mitchell, 2022). It is important to note that cleansing skin vigorously is never appropriate in a healthcare setting as this can cause skin irritation, damage the protective barrier, and increase the risk of infections, especially for patients with fragile or sensitive skin (McNichol et al., 2021). Evidence also suggests that using emollient products, such as moisturising products and lotions, may improve clinical measures of skin dryness which can increase risk of skin breakdown, compared to no intervention or standard care (Cowdell et al., 2020).

Hair

Hair is a large part of the integumentary system and has several functions. First, hair has a protective function. By trapping bacteria, debris, and harmful particles, the hair does not allow these offensive agents to enter the skin. Hair also blocks sunlight from the scalp, protecting against excess exposure to ultraviolet radiation. Hair provides warmth by trapping air close to the skin. Hair grows from the skin and when the skin produces sebum, it can build up on the hair shaft. An overabundance of sebum can build up if the hair or body is not regularly washed.

A common skin condition is folliculitis, which happens when hair follicles become inflamed; it can occur when the hair follicles become infected due to the buildup of sebum. When the scalp of the head is not regularly washed, dead skin, product residue, sweat, and dirt may also build, which results in an increased risk for infection, and unpleasant and greasy hair. In addition, prolonged periods of not washing the hair on the head can damage hair and impede its ability to grow. When the body is not regularly washed, the overproduction of sebum found on the skin can lead to oily skin or acne. Proper hair hygiene supports reducing those risks and aids in reducing bacterial and fungal growth. Bacteria and fungus can cause conditions such as ringworm, which is a common fungal infection of the skin, hair, or nails.

Nails

Proper nail hygiene prevents the spread of infection through bacteria hidden under the fingernails. Additional benefits of nail hygiene include preventing fungal infections under the nails, reduced risk of ingrown nails, and promoting proper nail growth. Therefore, proper cleaning under the fingernails and keeping the nails trimmed using clean tools are essential practices. Another benefit of properly trimmed nails is the minimised risk of lacerations that can result from a patient using unkept nails to scratch themselves or others. While assessing finger and toenails helps detect infections and issues with nail and skin integrity, in hospital settings, nail care is typically provided by specialist practitioners trained in foot and nail care (McNichol et al., 2021). Timely reporting of any concerns, such as discolouration, thickening, swelling, or signs of infection, is essential for ensuring prompt referral and appropriate intervention, helping to prevent further complications.

Oral Cavity

Good oral hygiene aids in maintaining the mouth, gums, lips, and teeth. A thorough oral hygiene assessment involves evaluating the patient’s mouth, teeth, gums, and overall oral health. This helps identify potential issues such as mouth dryness, infections such as candida albicans, ulcers, or plaque buildup, ensuring appropriate care is provided.

In Australia, the Oral Health Assessment Tool (OHAT) is a commonly used clinical tool for evaluating oral health, particularly in aged care facilities. It assesses eight key areas: lips, tongue, gums, saliva, natural teeth, dentures, oral cleanliness, and dental pain (Chalmers et al., 2005; Lewis & Fricker, 2008). While this tool was first validated in 2005 (Chalmers et al., 2005), OHAT is still frequently used in residential care settings, particularly for older adults, to identify and manage oral health concerns for non-dental professionals such as nurses and other healthcare workers (Pritchard et al., 2025).

When assessing oral hygiene, it is important to check for, document and report signs of oral health issues, including mouth soreness, inflammation, bad breath, dry oral tissues, thick saliva, bleeding gums, loose or broken teeth, oral pain, difficulty eating or speaking, and poor oral cleanliness. If dentures are used, assess for damage, missing parts, or identification markings (SA Dental, n.d). For guidance on how to perform an oral health assessment, watch the following video [6:32].

Assessing and providing oral health care can be particularly challenging when additional obstacles, such as cognitive decline, are prevalent. SA Health (Lewis & Fricker, 2008) has provided a publicly available resource that explains the OHAT and how to deal with the challenges of assessing and providing oral health care. You can access Oral Health Assessment Toolkit for Older People here.

Poor oral health can have many effects on an individual. For example, studies have shown the impact of oral health on the quality of life and well-being of individuals, including interference with eating, chewing and swallowing, resulting in nutritional issues and concerns with appearance, leading to embarrassment and social withdrawal (Pritchard et al., 2025). Good oral hygiene can give a patient a sense of well-being and positive self-esteem, resulting in improved mental health (Rasmussen et al., 2023). There is also an emerging body of evidence linking the effectiveness of oral care in clinical care settings to hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP), ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP), and other systemic health problems, highlighting the importance of oral care in reducing the incidence of these infections, improving patient outcomes, and decreasing healthcare costs through preventative oral hygiene practices. (Gallione et al., 2024; Hua et al., 2020; Tehan et al., 2024).

Despite the obvious importance of oral health, studies have shown that oral care is a commonly missed care which is a risk to patient safety, with one study finding oral care the third highest missed nursing care in an acute care setting after pressure area care and mobilising (Dagnew et al., 2020; Gallione et al., 2024). Additionally, ensuring the patient is involved in assessing oral care and their oral care needs, including allowing them to do as much as possible, has also been considered necessary in the literature (Koistinen et al., 2021; Rasmussen et al., 2023). Oral health assessment and care planning should consider patients’ perceptions and existing routines, and collecting oral health histories can support this person-centred approach (Murray et al., 2024). A recent study revealed the main barriers to providing oral care included patient uncooperativeness, inadequate staffing, and lack of oral hygiene resources. The most helpful strategies considered to facilitate improvement in oral care included patient reminders, prompts, and providing toothbrushes (Tehan et al., 2024).

Regular teeth brushing removes plaque, bacteria, and food particles to prevent tooth decay. These measures also massage the gums, help break up tissue or bacteria, increase blood flow, and relieve discomfort caused by unpleasant odours and tastes. Patients who are nil by mouth (NBM) or on a ventilator require frequent oral care every 2–4 hours to maintain oral hygiene and reduce infection risk. While mouth swabs can help with regular oral care, brushing the teeth with a toothbrush remains essential and should be performed at least twice daily to ensure thorough cleaning.

Perineum

The perineum includes the genital and rectal areas of the body, including the area in between. Because the perineal area is warm, dark, and moist, these areas become an optimal breeding ground for bacteria. Good perineal hygiene prevents infections such as urinary tract infections, removes discharges, eliminates bad odour, promotes comfort, alleviates itching, and reduces the risk of chafing and skin rashes. When assessing the perineum, it is important to check the skin’s condition in this area, looking for redness, swelling, rashes, irritation and any skin breakdown or pressure injuries, particularly for immobile patients. Also, observe for any signs of infection, discharge, odour, unusual colouring, excess moisture or dryness. Ask the patient if they are experiencing any pain, itching, burning or tenderness. Document any abnormalities thoroughly, as this information is crucial for developing an appropriate care plan. Based on the assessment, interventions such as increasing the frequency of perineal care or using lotions, barrier creams, specialised wipes, or medications as prescribed, can be implemented to address discomfort and prevent complications.

Mental Health

Poor hygiene can be a sign of self-neglect and may be affected by mental health (Ghassemi et al., 2023). Personal hygiene and grooming issues have been shown to negatively impact mood, motivation, social and work engagement, self-worth and self-esteem and engagement with treatment and subsequent recovery (Stewart et al., 2022). Those with obsessive-compulsive disorder may overindulge in hygiene practices, which can take up much of their time as well as lead to skin breakdown or pain, depending on their compulsions. As previously discussed, poor oral hygiene can lead to tooth decay or bad breath. This can have a negative impact on self-esteem as one may be embarrassed to smile or socialise with others. Research supports the effectiveness of person-centred approaches in assessing, engaging with, and intervening when a decline in personal hygiene and grooming is observed (Stewart et al., 2022). Good hygiene and self-care practices can improve mood, decrease stress levels, provide a sense of well-being, and prevent or limit anxiety while boosting an individual’s self-esteem and confidence. Regular assessment of hygiene practices allows healthcare providers to identify challenges early, offer appropriate support, and implement person-centred interventions that promote dignity, independence, and overall well-being (Stewart et al., 2022).

Factors Affecting Hygienic Practices

|

Hygiene measures and practices can promote health and prevent disease. These measures and practices may differ among various groups and people. It is important to remain culturally sensitive when encountering preferences that may differ from your own. Respecting patient differences and preferences in hygiene practices while remaining unbiased is essential to nursing practice. Nurses must also remember to provide care and education to patients in a nonjudgmental manner.

|

Psychological Factors Affecting Personal Hygiene

|

Psychological factors that may affect personal hygiene include cognitive diseases as well as an individual’s mental health status. The psychological factors will impact a person’s ability to perform hygiene as well as the patient’s motivation for or memory of these practices. It is imperative the nurse assesses any psychological factors that might inhibit a person’s personal hygiene habits.

|

The Nurses’ Role in Hygiene

Nurses play a critical role in assessing a patient’s preferences, physical limitations, and cognitive status to develop and implement an individualised hygiene and health care plan. When planning hygiene care, it is essential to consider the patient’s level of independence, which may range from complete independence to requiring partial or full assistance from a nurse or nursing assistant. Ensuring patient safety is a primary concern when scheduling and providing hygiene care.

This section will examine the key steps for assisting patients with hygiene, with considerations specific to older adults, and strategies for promoting healthy hygiene practices through patient education.

Assisting with Patient Hygiene

When assisting the patient with hygiene, the nurse must integrate the individual’s preferences into the plan of care. The nurse performs a physical assessment to determine the adequacy of the patient’s hygiene practices. For the recognised practices to be deemed inadequate, a distinct health threat must exist. For example, upon examining the oral cavity, if gingivitis or periodontitis is visible, the patient may be at a higher risk for conditions such as heart disease, stroke, arthritis, and diabetes if left untreated.

For patients with intravenous (IV) access, the bag of IV fluids and IV tubing may be threaded through the sleeve of the gown to keep the system intact. There are covers available to keep the site dry during bathing. Dressing changes for the IV must follow facility protocols. Finally, the nurse must try to preserve the patient’s privacy throughout the bathing process. To accomplish such privacy, a nurse should reveal only the areas about to be cleaned and keep the rest of the body covered, ensuring the door and/or curtains remain closed. The nurse needs to encourage the individual to perform all tasks as independently as appropriate. Using the bath or various hygienic procedures is an excellent opportunity for the nurse to assess the person’s skin, cognition, and mobility status. These simple tasks can reveal subtle changes in the patient’s status and allow for early intervention.

In addition, whether the individual is conscious or not, the nurse must introduce themselves and always inform the patient of what is about to happen and why. This will obtain consent and complement the nurse’s professional demeanour. Research suggests that unconscious patients may hear what others are saying. Nurses who continue to introduce themselves and explain procedures before proceeding will decrease the stress on the individual through their journey to consciousness in a strange and foreign environment.

When a patient requires assistance with showering, the nurse must ensure a safe and comfortable experience while respecting the individual’s dignity and preferences. The following step-by-step process outlines key considerations for preparing the environment, providing support, and maintaining patient safety throughout the showering process.

Procedure For Assisting with a Shower

There are several reasons why a patient may be unable to wash themselves and require a bed bath. Patients who are critically ill or have severe physical limitations, such as those recovering from surgery, experiencing significant pain, or suffering from conditions like stroke or paralysis, may lack the strength or mobility to perform self-care tasks. Additionally, patients with cognitive impairments, such as dementia or delirium, may be unable to understand or remember how to bathe themselves. Bed baths are also necessary for patients who are on strict bed rest due to medical conditions like severe heart failure or respiratory distress, where movement could exacerbate their condition. Providing a bed bath not only ensures the patient’s hygiene but also offers an opportunity for nurses to assess the patient’s skin condition, promote comfort, and maintain their dignity.

When a patient is unable to wash themselves independently, the nurse must follow a structured approach to ensure thorough hygiene while maintaining the patient’s comfort, dignity, and safety. The following step-by-step process outlines best practices for providing a bed bath, including preparation, technique, and considerations for patient privacy and skin integrity.

Procedure for Bed Bathing a Dependent Person

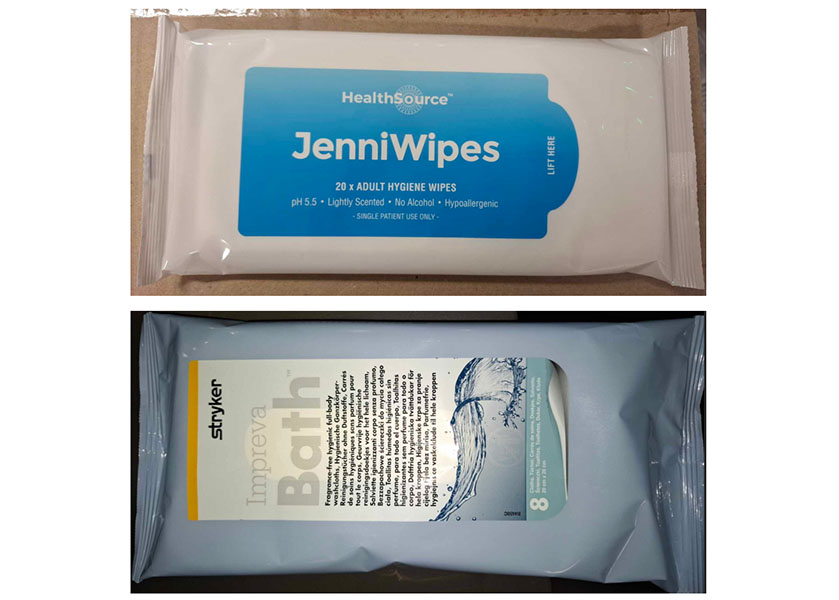

When a full bed bath is not practical on a daily basis, or when a quick cleanse is needed, such as after surgery, heated bed bath wipes offer a convenient and effective solution (Sharp & Campbell, 2022).

To use heated bed bath wipes, follow these steps:

- Warm the wipes according to the manufacturer’s instructions, typically using a microwave or a specialised warmer.

- Ensure the wipes are at a safe and comfortable temperature before applying them to the patient’s skin.

- Gently clean the patient’s body, starting from the face and moving downwards, using a new wipe for each area to prevent cross-contamination.

- Pay special attention to skin folds and areas prone to moisture buildup, such as under the armpits, breasts and in the groin area.

- After cleaning, allow the skin to air dry.

In some cases, a shower bed can be used to take a patient to the shower. This approach allows patients who have limited mobility but are still able to be transported, to experience the benefits of a full shower. Using a shower bed can help improve the patient’s overall hygiene, boost their morale, and provide a sense of normalcy and dignity. It also allows for a more thorough cleaning compared to a bed bath, which can be particularly beneficial for patients with skin conditions or those who are prone to infections. Additionally, the warm water and the act of showering can have therapeutic effects, promoting relaxation and comfort.

Maintaining a clean and hygienic environment in a hospital is paramount for preventing the spread of infections and ensuring patient comfort. As a nurse, it is essential to change bed sheets at least daily or whenever they become soiled. The following sections outline the procedures for making an unoccupied bed and for making an occupied bed when patients cannot easily be moved out of the bed. These tasks are fundamental responsibilities for nurses, ensuring that patients receive the highest standard of care and hygiene.

Procedure for Making an Unoccupied Bed

Procedure for Making an Occupied Bed

Oral Care

Care of the oral cavity, oral hygiene, helps preserve a healthy state of the lips, gums, teeth, and mouth. Brushing the teeth removes plaque, food particles, and bacteria as well as massages the gums and alleviates any discomfort that may be caused by tastes or unpleasant odours. Patients should be encouraged to brush their own teeth when possible. Independent individuals should be offered supplies to also carry out personal hygiene needs as appropriate. If the patient is unable to do so independently, the nurse or appropriate delegate (i.e., the person who is delegated a responsibility by the nurse) will need to assist with or perform the oral care for this individual. Patients who are unable to perform their own oral care may require care every one to two hours, if and as necessary. Individuals who are either unable to breathe through the nose or are mouth breathers will need more frequent oral care. More frequent care will ensure that the integrity of the oral mucous is maintained. The nurse must ensure that suction equipment is available to prevent aspiration, raise the head of the bed to 30–45 degrees, use suction to remove excess fluid/secretions, routinely moisten the mouth, and apply lip balm to prevent lips from cracking.

Teeth should be brushed twice daily, and the mouth should be rinsed with water after meals. The toothbrush should be soft-bristled and reach all the teeth. Automatic toothbrushes may be adequate substitutes for patients with arthritis or other conditions that impair their ability to brush adequately. Because the toothbrush cannot reach the areas between the teeth, flossing is recommended once a day to remove food particles and plaque. Water picks, pressured water spray units, and cone-shaped brushes may be used when patients are unable to use floss or perform their own oral hygiene. Toothpaste and other powders aid in the brushing process. Mouthwashes may also be used to reduce bacteria, plaque, tartar, and gingivitis. Many mouthwashes also freshen breath and can protect tooth enamel.

The following step-by-step process outlines how to safely and effectively support a patient with oral care, ensuring comfort, preventing complications, and promoting good hygiene practices.

Procedure for Assisting a Person with Oral Care

Denture Care

Artificial teeth not permanently implanted, called dentures, are the patient’s personal property and must be handled with care. Dentures should soak in a labelled, enclosed cup to be stored when not being worn. Many patients do not wear dentures when sleeping, and dentures must be removed for surgeries or other diagnostic procedures. Many patients also prefer to wear dentures as soon as they wake up or come out of a procedure to avoid embarrassment due to feeling self-conscious without them. If the patient goes for long periods of time without wearing the dentures, the gum line may change and affect the fit of the dentures. It is also recommended that dentures not be worn twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week. Patients are usually familiar with the necessary care of dentures to prevent infection and irritation and prefer to perform denture care according to standard practice at home.

Procedure for Providing Denture Care

Eyes, Ears, and Nose

Special attention is given to care of the eyes, ears, and nose due to the sensitivity of these areas, and taking exceptional care to avoid injury is important. The nurse should ask the patient about any specific care the patient normally performs in relation to the eyes, ears, and nose. For example, some people prefer using cotton swabs to clean the outer parts of the ears. The nurse should also be aware of any use of hearing or visual aids, such as eyeglasses, hearing aids, or contacts. The nurse should also ask the patient about any history or treatments of eye, ear, or nose problems. The circular areas around the eyes are usually cleaned during the bath with the use of a clean washcloth, moistened with warm water. Soap may cause burning or irritation, so avoiding soap around the eyes is advisable.

The eye should be cleaned from the inner to outer canthus. A separate section of the washcloth should be used each time to avoid the risk of spreading infection. If the patient has dried exudate (dried or crusty fluid) that is not easily loosened, try placing a damp gauze or cotton ball on the lid margins to loosen secretions. Avoid applying direct pressure over the eyeball as this may cause injury. Remove any exudate from the eyes carefully and as often as needed to keep the eye clean. Unconscious patients may require more frequent eye care due to the buildup of secretions from the absence of the blink reflex. eye care is essential for patients who are unconscious or dependent, such as those in a coma, under sedation, or with severe physical or cognitive impairments. These patients are unable to blink or close their eyes effectively, which can lead to dryness, irritation, and potential infections. Proper eye care helps maintain eye health and prevent complications in these vulnerable individuals. Click or press on the steps below to understand the process of providing eye care for a dependent patient.

Procedure for Providing Eye Care for an Unconscious or Dependent Person

The ears are also cleansed during a shower or bed bath. The ear canal should be cleaned with a gentle rotation using a moistened washcloth. A cotton swab is useful for cleaning the pinna or outer aspects of the external ear. Educating patients to never use toothpicks, cotton swabs, or any other device to clean the internal auditory canal is important, as the tympanic membrane can easily be damaged through this action.

Care of the nose includes clearing secretions. Most patients can gently blow into a disposable paper tissue. The individual should avoid harsh blowing as this can cause pressure capable of injuring the nasal mucosa, sensitive eye structures, and the tympanic membrane. The patient should blow with both nostrils open to avoid forcing debris into the eustachian tubes. If the external nares are crusted, a warm, moist compress may be used to help soften and remove any exudate. A moist washcloth or cotton swab may be used to clean the opening of the nares but should never exceed past the nares to avoid injury.

Contacts and Glasses

Eyeglasses are often expensive and are the patient’s personal property. Therefore, eyeglasses should be stored in a case or bedside drawer when not in use to prevent damage or loss. Eyeglasses may require special cleaning with the use of cloths made of soft microfiber, cleansing solutions, or lens wipes. Washcloths, paper towels, and tissue paper should be avoided because they can scratch the lenses. Various types of contact lenses are available, ranging from daily, weekly, or even monthly use. Some patients may sleep in contact lenses, while others cannot or prefer not to leave these lenses in the eyes overnight. The nurse must assess the type of contacts the person wears and any preferred special care measures.

Several products are available for lens care, such as saline solutions and hydrogen peroxide solutions. Most patients will prefer to care for their own lenses but should not wear these contacts if unable to independently insert and remove the lenses. Contacts should remain clean and sterile. Reusable lenses should soak in a solution of the owner’s choosing when not in use to keep the lens from drying out. Hand hygiene when inserting or removing contacts is essential to prevent infection. A towel may be placed in the sink to prevent a dropped contact from accidentally falling into the drain.

Hearing Aids

Hearing loss is a common health problem. The ability to hear impacts a person’s ability to communicate and react appropriately to things in their environment, and many patients have hearing aids. The care of hearing aids includes battery care, proper insertion, and routine cleanings. The nurse should determine the patient’s normal method of cleaning the hearing aids. In addition, the nurse should assess the quality of the patient’s hearing with the use of the devices to ensure effectiveness and functionality. Hearing aids should not be used when water exposure is a risk to avoid damage to the devices. When hearing aids are not in use, the devices should be labelled and stored in a case or a safe place to avoid damage or loss. The battery should also be removed or turned off when not in use to preserve battery life. The hearing aids may be cleaned with a dry, soft cloth.

Hair

Hair care will depend greatly on the patient’s preferences, culture, and physical and cognitive limitations. Hair should be shampooed as often as necessary or per individual preference. The brush and comb should be washed each time the hair is washed, or as appropriate. Prior to shampooing the hair, brush or comb the hair to stimulate the scalp and untangle the hair. Whenever possible, encourage the patient to brush and wash their own hair. In the event regular shampooing is contraindicated for various conditions, bedside products such as foams, dry powders, or concentrates that do not require rinsing may be used.

Shampoo caps are also available and should be warmed in the microwave if they are not stored in a warmer. Once the cap is on the patient’s head, massage the hair and scalp to lather the shampoo according to the manufacturer’s directions, and discard after use. Towel dry the hair after each type of cleansing, followed by combing and styling to the patient’s preference. If a hair dryer is not appropriate or available, the hair should be covered with a towel until dry to minimise the individual becoming chilled. Some healthcare facilities may have beauticians or barbers to assist with hair care, but this does not dismiss the nurse’s obligation.

Hair type should also be considered with hair care. For tightly curled hair, a wide-toothed comb is best to untangle the hair, working from the neckline to the forehead. This hair type may also prefer small braids that do not need to be undone for shampooing. Application of a lubricant oil should be applied to the braids to prevent hair breakage. Those individuals with alopecia and/or baldness should still cleanse and moisturise the scalp to prevent dryness. Dandruff may also be present and is not considered contagious or infectious. Dandruff and hair loss may be embarrassing for a patient, so the nurse must remain professional and preserve the person’s dignity.

If a patient is unable to wash their hair independently or cannot get out of bed, the nurse may need to assist with washing their hair. The following step-by-step process outlines how to properly wash a patient’s hair in bed.

Procedure for Washing a Person’s Hair in Bed

While washing a patient’s hair in bed may be therapeutic and comforting for a patient, this process can be quite time-consuming and not always practical. Shampoo caps are a convenient and effective solution for maintaining hair hygiene in hospital settings, especially for patients who are bedridden or have limited mobility. These caps allow for a thorough hair wash without the need for water or rinsing, making the process quick and comfortable for the patient.

To wash a patient’s hair using a shampoo cap is extremely easy. You can watch an instructional video here [1:29], or follow the simple instructions below:

-

- Place the cap over the patient’s head, ensuring all hair is tucked inside.

- Gently massage the cap, distributing the cleansing solution evenly through the hair.

- Continue massaging for 1–3 minutes to ensure thorough cleaning.

- Carefully remove the cap, wiping away excess moisture if needed.

- Use a towel to pat hair dry or allow it to air dry.

Nails

Nails may harbour bacteria, so maintaining nail care to prevent the risk of infection or injury from scratching is crucial. Nurses must follow the agency’s policy related to nail care, as some facilities do not allow nail trimming by clippers. If allowed, nails should be trimmed straight across and then rounded at the tips in a gentle curve. The nails should not be trimmed too short as the skin and cuticles may become injured. Hangnails, which are broken pieces of cuticle, should be cut off with cuticle scissors and not torn or ripped off. Cuticles should be gently pushed back, after softening by washing with warm water, using a cloth or blunt instrument. A moisturiser or emollient may be applied to the nails and cuticle to prevent hangnails. The underside of the nails should be cleaned with a blunt instrument or nail brush. Damaging the area where the underlying tissue and nail are attached by being forceful is discouraged. Once the care is completed, a massage of the hands using lotion may increase blood flow and provide comfort.

Feet

Feet also require special attention to prevent odours, injury, and infection. Poor care of the feet may result in conditions such as calluses, neuropathy, pain, ingrown toenails, or deformities. Feet may be cleaned in the shower or using a basin with tepid water and mild soap for bedside baths. The feet should not be soaked. Feet should be dried immediately after being washed. Lotion may be applied and massaged on the feet to promote circulation and provide comfort. Toenails should also be kept short to minimise bacteria underneath the nail. Care of the toenails is very similar to the care of fingernails.

Patients with diabetes may have reduced sensation in their feet and must be taught how to examine and care for their feet daily. Some patients may need to see a podiatrist for treatment of corns, calluses, or bunions. The nurse should also educate the individual or ensure the use of cotton socks for warmth and perspiration absorption, as well as the importance of properly fitting footwear to avoid complications.

Perineal Care

Perineal care, also known as peri-care, includes hygiene care of the genital and rectal areas of the body, including the area in between. Perineal care is a vital aspect of personal hygiene, especially for individuals who are bedridden, incontinent or have limited mobility. It involves cleansing and maintaining the skin around the genital and anal areas to prevent infection, discomfort, and skin breakdown. Since this area is prone to infection, it should be cleaned at least once daily and more frequently if the individual experiences incontinence. Regular perineal care has been shown to reduce the risk of catheter-associated Urinary Tract Infections (CAUTI) and incontinence-associated dermatitis (IAD) (Crowson et al., 2023; McNichol et al., 2021; Queensland Health, 2023).

Perineal care is typically provided during daily bathing, after bedpan use, and after incontinence episodes to maintain hygiene and prevent infection. Patients who can perform hygiene independently may prefer to cleanse on their own, however, may need prompting. Patients unable to perform this practice independently may request someone of the same gender to assist with perineal care or a bath in general. This request must be communicated and followed as best as possible. Patients who require help may include those who have physical or cognitive limitations. Individuals who are postpartum, recovering from rectal or genital surgery, suffer from incontinence or have an indwelling catheter require meticulous care to avoid infection (Crowson et al., 2023; Girsang & Elfirae, 2023; McNichol et al., 2021).

Other instances that may also cause vaginal or perineal problems include douching, some sexually transmitted infections (STI), diabetes mellitus, and urinary or faecal incontinence. Maintaining a professional attitude, preserving the patient’s dignity, ensuring privacy, and gaining permission to touch the patient is important when aiding in perineal care regardless of consciousness. The nurse needs to remember to always clean from the least contaminated areas to the most contaminated areas to prevent infection.

Click or press on the following steps detailing the procedure for providing perineal care in a hospital setting for individuals unable to manage their own hygiene.

Procedure for Providing Perineal Care

The buttocks, groin and any skin folds may need extra protection against moisture and potential skin breakdown. Barrier wipes can provide a protective layer on the skin to prevent irritation and breakdown. Multifunction products such as these can be used to cleanse and protect the skin by utilisation of a moisture barrier skin protectant and are particularly beneficial for patients who are incontinent, bedridden, or have sensitive skin, as these individuals are more prone to developing pressure injuries, incontinent-associated dermatitis and skin infections (McNichol et al., 2021). Additionally, research has shown that barrier wipes can significantly reduce IAD prevalence compared to the standard practice of water and pH-neutral soap (Beekman et al., 2011). The wipes effectively create a barrier that shields the skin from moisture and other irritants, helping to maintain skin integrity and promote healing.

Sitz baths may also be used after childbirth, rectal surgery, or vaginal surgery. This treatment may also be used to relieve discomfort from fissures or haemorrhoids. A sitz bath is most often performed on the toilet with a tub lining the bowl. The tub is filled with three to four inches of warm, not hot, water. The patient will submerge the pelvic area for twenty to thirty minutes to reduce inflammation. Other options for cleansing the perineal and vaginal areas of a patient who is postpartum include either a shower or sitting on a stool using a perineal irrigation bottle.

Catheter Care

Indwelling catheters (IDCs) are associated with urinary tract infection (UTI) and therefore require particular hygiene care to prevent complications. When a catheter is considered the cause of a UTI, this is called catheter-associated UTI (CAUTI). Catheter care is usually performed after perineal care and is generally ordered twice daily. Prior to performing routine catheter care, practitioners should always pay close attention to how long the catheter has been inserted, consider whether the catheter is needed, and request confirmation from the medical officer as to whether it is still required or if it can be removed. Prompt removal and precise cleaning can help to avoid an associated infection (ACSQHC, 2021).

According to the Australian Guidelines for the Prevention and Control of Infection in Healthcare, nurses and other healthcare workers should be familiar with the policies and procedures for the safe insertion, maintenance and removal of IDCs (ACSQHC, 2019). When maintaining the care of an IDC, the following should be performed (ACSQHC, 2019):

- Conduct a daily review to assess the need for the urinary catheter

- Ensure the catheter remains continuously connected to the drainage system

- Educate patients on their role in preventing urinary tract infections; if not possible, perform daily perineal hygiene and catheter care

- Empty urinary drainage bags frequently to maintain urine flow and prevent reflux

- When emptying catheter bags, use a separate urine collection container for each patient, preventing contact between the drainage bag and the container

- Before catheter care, perform hand hygiene and wear gloves, an apron, and goggles; remove the gloves and apron and perform hand hygiene afterwards.

Click or press on the steps below for a detailed guide on providing catheter care.

Procedure for Providing Catheter Care

Lifespan Considerations

|

Older Adults Lifespan considerations for the older adult include age-related changes that require special focus and nursing strategies. Age-related changes include impaired physical mobility, impaired oral mucous membranes, and an increased risk for impaired skin integrity. Older adults are also more likely to become chilled when left uncovered during bathing. The room should be maintained at a warmer temperature, and drapes should be used during care to provide modesty and avoid chilling. Older adults also may experience neurologic changes or impaired circulation that impede the ability to sense temperature changes in water. Using caution to prevent burns or injury to the skin is also important to remember. In addition, frequent bathing and use of soaps may have harmful effects on the skin. Impaired physical mobility related to ageing includes decreased dexterity and muscle strength, compromised functional mobility, and decreased range of motion. Examples of chronic conditions that compromise functional ability include heart disease, diabetes mellitus, rheumatoid arthritis (RA), coronary heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and osteoarthritis. Patients with deficits after a stroke, Parkinson’s disease, or other neurologic disorders may also experience physical limitations. Part of the ageing process also includes a loss of elasticity, reduced blood supply to connective tissue, and degeneration of epithelial cells that lead to impaired mucous membranes. Older patients are also likely to have impaired oral mucous membranes due to the decreased production of saliva and medications that cause dry mouth. For example, decongestants, antidepressants, antihistamines, blood pressure medications, Alzheimer’s disease medications, analgesics, and diuretics may cause dry mouth. Older adults are also at risk for impaired skin integrity due to the loss of elasticity, thinning of the epidermis and subcutaneous fat, and dryness caused by decreased activity of oil and sweat glands. The older adult’s nails may become opaque, brittle, scaly, tough, or hypertrophied. These skin-related changes may also be visible in the feet. Older adults are at an increased risk of friction shear and pressure ulcers due to age-related skin changes and impaired mobility.

|

|

Infants and Children

When providing hygiene care for infants and children, it is essential to consider their unique developmental needs and ensure a compassionate and supportive approach. Effective communication, comfort, safety, privacy, and parental involvement are crucial elements in delivering high-quality care. Tailoring hygiene practices to the child’s age and developmental stage not only enhances their comfort and cooperation but also fosters a positive and trusting relationship between the child, their caregivers, and healthcare professionals. The following considerations outline key strategies for addressing these aspects during hygiene care procedures.

|

Promoting Hygiene Health Education

One of the most essential roles nurses have in disease prevention and health promotion is through education. The nurse should assess a patient’s knowledge about hygiene as well as individual cultural and personal preferences. The nurse should educate people on the importance of good hygiene practices. In addition, good hygiene can aid in preventing the spread of diseases to others, promote self-esteem, and boost mood. Once the nurse assesses the patient’s knowledge and ensures understanding, the nurse should educate the person on the steps needed to perform hygiene to avoid infection or injury. The nurse should also assess a patient’s ability to perform care independently by performing a head-to-toe assessment. The nurse should reinforce proper steps as needed while educating and giving instructions on the importance of diet and nutrition to promote healthy skin and mobility.

Consolidating your Knowledge

This clinical scenario is designed to help you apply your knowledge of hygiene care in a practical, patient-centred context. As you read through the case of Mr George Reynolds, consider the importance of comprehensive hygiene assessment and individualised care planning in maintaining patient comfort, dignity, and health.

Clinical Scenario: Addressing the hygiene needs of Mr George Reynolds

Name: Mr George Reynolds

Age: 78

Medical history: Type 2 diabetes, mild cognitive impairment, and limited mobility due to a recent stroke.

Current status: Admitted to the medical ward for management of a urinary tract infection (UTI) and ongoing rehabilitation.

Scenario:

During your morning round, Mr Reynolds appeared uncomfortable and restless. He expressed itching and tenderness in his perineal area and mentioned he hadn’t had his oral care attended to since the previous evening. On assessment, his skin was dry and flaky, and his perineal area showed signs of redness and irritation. His oral cavity was dry, and food residue was present, suggesting inadequate oral hygiene.

You recognise that Mr Reynolds’ hygiene needs require immediate attention to prevent further skin breakdown and infection. You develop a personalised hygiene plan.

Questions for reflection:

Create a care plan for Mr Reynolds’ hygiene needs. To prioritise his hygiene needs you should:

- Identify any further assessments you would undertake

- Identify problems and potential problems

- Formulate care goals for Mr Reynolds and expected outcomes

- Identify the interventions you would implement.

NB: You might like to follow the nursing care planning process from the Developing Person-Centred Care Plans through Clinical Reasoning chapter to assist in formulating Mr Reynolds’s hygiene care plan.

- What steps would you take to address Mr Reynold’s hygiene needs while maintaining his dignity and comfort?

- How would you assess and document his skin, perineal area, and oral health?

- What interventions would you implement to manage his dry skin and prevent infection?

- How would you involve Mr Reynolds in his hygiene care plan to promote independence and person-centred care?

Key Takeaways

In this chapter, we covered:

- What hygiene is and the various factors that impact a person’s ability to maintain personal hygiene independently such as cultural preferences, socioeconomic status, developmental level, personal preference and impaired mobility

- How to assess personal hygiene including observing: skin, hair, nails, oral cavity and perineum

- Psychological factors that affect personal hygiene including cognitive diseases, mental health and body image

- The nurses role in hygiene such as procedures for assisting with a shower, bed bathing a dependent person, making an occupied and unoccupied bed, assisting with oral care and denture care, eye care, washing a person’s hair in bed, providing perineal care, and catheter care.

- Considerations for different lifespans such as the older adult and age related changes that can affect hygiene practices and approaches for assisting infants and children

- Promoting hygiene health education to ensure understanding of the importance of good hygiene practices.

References

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. (2019). Australian guidelines for the prevention and control of infection in healthcare. Australian Government. www.safetyandquality.gov.au/sites/default/files/2024-08/australian-guidelines-for-the-prevention-and-control-of-infection-in-healthcare.pdf

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. (2020). Preventing pressure injuries and wound management. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/publications-and-resources/resource-library/nsqhs-standards-preventing-pressure-injuries-and-wound-management

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. (2021). National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards (2nd ed.). https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/sites/default/files/2021-05/national_safety_and_quality_health_service_nsqhs_standards_second_edition_-_updated_may_2021.pdf

Berman, A., Snyder, S., Levett-Jones, T., Burton, T., & Harvey, N. (2021). Skills in clinical nursing (2nd ed.). Pearson Australia.

Bonifant, H., & Holloway, S. (2019). A review of the effects of ageing on skin integrity and wound healing. British Journal of Community Nursing, 24(Sup3), S28–S33

Chalmers, J. M., King, P. L., Spencer, A. J., Wright, F. A. C., & Carter, K. D. (2005). The oral health assessment tool: Validity and reliability. Australian Dental Journal, 50(3), 191-199. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1834-7819.2005.tb00360.x

Cowdell, F., Heague, M., & Dyson, J. (2023). Barriers and facilitators to skin hygiene care and emollient use in residential care homes: Instrument design and survey. International Journal of Older People Nursing, 18(4), e12550. https://doi.org/10.1111/opn.12550

Cowdell, F., Jadotte, Y. T., Ersser, S. J., Danby, S., Lawton, S., Roberts, A., & Dyson, J. (2020). Hygiene and emollient interventions for maintaining skin integrity in older people in hospital and residential care settings. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2020(1), CD011377. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011377.pub2

Cremer, S., Vluggen, S., Man-Van-Ginkel, J. M., de Metzelthin, S. F., Zwakhalen, S. M., & Bleijlevens, M. H. C. (2023). Effective nursing interventions in ADL care affecting independence and comfort: A systematic review. Geriatric Nursing, 52, 73–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2023.04.015

Dagnew, Z. A., Abraham, I. A., Beraki, G. G., Tesfamariam, E. H., Mittler, S., & Tesfamichael, Y. Z. (2020). Nurses’ attitude towards oral care and their practicing level for hospitalized patients in Orotta National Referral Hospital, Asmara-Eritrea: A cross-sectional study. BMC Nursing, 19(1), 63–63. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-020-00457-3

Gallione, C., Bassi, E., Basso, I., Airoldi, C., Barisone, M., Molon, A., Di Nardo, G., Torgano, C., & Dal Molin, A. (2024). Missing fundamental nursing care: What’s the extent of missed oral care? A cross-sectional study. Nursing Reports, 14(4), 4193–4206. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14040305

Ghassemi, E. Y., Thorseth, A. H., Le Roch, K., Heath, T., & White, S. (2023). Mapping the association between mental health and people’s perceived and actual ability to practice hygiene-related behaviours in humanitarian and pandemic crises: A scoping review. PloS One, 18(12), e0286494. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0286494

Giuliano, K. K., Penoyer, D., Middleton, A., & Baker, D. (2021). Original research: Oral care as prevention for nonventilator hospital-acquired pneumonia: A four-unit cluster randomized study. The American Journal of Nursing, 121(6), 24–33. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NAJ.0000753468.99321.93

Goldenhart, A. L., & Nagy, H. (2022). Assisting patients with personal hygiene. In W. B. Ackley, T. S. Adolphe, T. C. Aeby, N. R. Aeddula, S. Agadi, P. Agasthi, S. Ahmad, A. Ahmed, F. W. Ahmed, I. Ahmed, R. A. Ahmed, S. W. Ahmed, A. M. Akanmode, R. Akella, S. M. Akram, Y. Al Khalili, E. Al Zaabi, M. H. Alahmadi, G. Alexander, … H. Zulfiqar (Eds).StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved March 3, 2025 fromhttps://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK563155/

Hua, F., Zhao, T., Wu, X., Zhang, Q., Li, C., & Worthington, H. V. (2020). Oral hygiene care for critically ill patients to prevent ventilator‐associated pneumonia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2020(12), CD008367-. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD008367.pub4

Koistinen, S., Ståhlnacke, K., Olai, L., Ehrenberg, A., & Carlsson, E. (2021). Older people’s experiences of oral health and assisted daily oral care in short-term facilities. BMC Geriatrics, 21(1), 1–388. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02281-z

Konno, R., Kanzaki, H., Stern, C., & Lizarondo, L. (2021). Assisted bathing of older people with dementia: A mixed methods systematic review protocol. JBI Evidence Synthesis, 19(2), 513–520. https://doi.org/10.11124/JBIES-20-00160

Lewis, A. & Fricker, A. (2008). Better oral health in residential care: Oral health assessment toolkit for older people. SA Health. https://www.dental.sa.gov.au/assets/downloads/Care-for-older-people-toolkit/Acute-settings/OHAT-Toolkit-for-older-people.pdf

McNichol, L., Wound, O., Ratliff, C., & Yates, S. (2021). Wound, ostomy, and continence nurses society core curriculum : Wound management (2nd ed.). Wolters Kluwer Health.

Mitchell, A. (2022). Skin assessment in adults. British Journal of Nursing, 31(5), 274–278. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2022.31.5.274

Murray, J., Paunovic, J., & Hunter, S. C. (2024). More than a mouth to clean: Case studies of oral health care in an Australian hospital. Gerodontology, 41(4), 486–498. https://doi.org/10.1111/ger.12736

Pritchard, L., Burden, K.-J., Carlson-Jones, W., Stormon, N., & Do, L. (2025). Implementation and acceptance of oral health assessment tools in residential aged care facilities: A scoping review. Gerodontology. https://doi.org/10.1111/ger.12811

Rasmussen, I. L., Halberg, N., & Jensen, P. S. (2023). “Why doesn’t anyone ask me”? Patients’ experiences of receiving, performing and practices of oral care in an acute orthopaedic department. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 37(4), 1079–1090. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.13182

SA Dental (n.d.). Oral health assessment. Government of South Australia. https://www.dental.sa.gov.au/professionals/oral-health-resources/care-for-older-people-toolkit/acute-settings/oral-health-assessment#:~:text=Assessment%20tools-,Oral%20health%20assessment%20tool%20(OHAT),dental%20pain

Sharp, C., & Campbell, J. (2022). Reducing skin tears, workload, and costs in the frail aged: Replacing showers with bath cloths. Asian Journal of Medical Sciences, 13(2), 181–184. https://doi.org/10.71152/ajms.v13i2.3830

Somrongthong, R., Wongchalee, S., Ramakrishnan, C., Hongthong, D., Yodmai, K., & Wongtongkam, N. (2017). Influence of socioeconomic factors on daily life activities and quality of life of Thai elderly. Journal of Public Health Research, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.4081/jphr.2017.862

Stewart, V., Judd, C., & Wheeler, A. J. (2022). Practitioners’ experiences of deteriorating personal hygiene standards in people living with depression in Australia: A qualitative study. Health & Social Care in the Community, 30(4), 1589–1598. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.13491

Tehan, P. E., Browne, K., Matterson, G., Cheng, A. C., Dawson, S., Graves, N., Johnson, D., Kiernan, M., Madhuvu, A., Marshall, C., McDonagh, J., Northcote, M., O’Connor, J., Orr, L., Rawson, H., Russo, P., Sim, J., Stewardson, A. J., Wallace, J., … Mitchell, B. G. (2024). Oral care practices and hospital-acquired pneumonia prevention: A national survey of Australian nurses. Infection, Disease & Health, 29(4), 212–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.idh.2024.04.006

Verstraten, C. C. J. M. M., Metzelthin, S. F., Schoonhoven, L., Schuurmans, M. J., & Man‐van Ginkel, J. M. (2020). Optimizing patients’ functional status during daily nursing care interventions: A systematic review. Research in Nursing & Health, 43(5), 478–488. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.22063

Chapter Attribution

This chapter has been adapted in parts from:

Fundamentals of nursing (2024) edited by Christy Bowen, Lindsay Draper and Heather Moore, OpenStax, is used under a CC BY licence.

Media Attributions

- Handwashing © Ben Green is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Incontinence-Associated Dermatitis © Maria Magdelena, Linda Andreyani & Suriadi, used with permission, as outlined in the Terms and Conditions is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- Child Brushing Their Teeth © Ben Green is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Bath Wipes © Tracey Gooding is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Shower Bed © Tracey Gooding is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Shower Cap © Tracey Gooding is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Barrier Wipes © Tracey Gooding is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Catheter Care © Ben Green is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license