Assessing and Supporting Mobility

Leisa Sanderson

Learning Outcomes

In this chapter you will learn how to:

- Describe the impact of immobility on body systems

- Implement nursing interventions to prevent complications of immobility

- Assess a patient’s mobility status and level of assistance required when transferring or mobilising

- Select and utilise appropriate manual handling assistive devices

- Demonstrate safe technique during all manual handling procedures

- Explain key strategies related to falls prevention.

|

|

Mobility, which includes moving one’s extremities, changing positions, sitting, standing, and walking, helps avoid degradation of many body systems and prevents complications associated with immobility. A person may find themselves with impaired mobility due to illness, injury, surgery, or chronic musculoskeletal conditions. Nurses assist patients to be as mobile as possible based on their individual circumstances, to achieve their highest level of independence, prevent complications, and promote a feeling of well-being. This chapter will discuss nursing assessments and interventions related to promoting mobility. |

Mobility

As a nurse, it is important to understand the importance of mobility, how internal and external factors can affect patient mobility, and how immobility affects the body. Proper understanding and assessment of a patient’s mobility can help guide their plan of care and shape realistic outcome goals in treatment.

A person’s mobility is the ability of a patient to change and control their body position. Physical mobility requires sufficient muscle strength and energy, along with adequate skeletal stability, joint function, and neuromuscular synchronisation. Anything that disrupts this integrated process can lead to impaired mobility or immobility. Mobility exists on a continuum ranging from no impairment (the patient can make major and frequent changes in position without assistance) to being completely immobile (the patient is unable to make even slight changes in body or extremity position without assistance). Factors that affect a patient’s mobility status can be internal or external.

Internal Factors

An internal factor that affects mobility is a factor that influences the patient from within, such as a physiological, sociocultural, psychological, or spiritual factor that is specific to each individual. Examples include hearing and visual function, chronic disease, congenital abnormalities, fatigue, stress, balance issues and previous falls history, personal attitude toward self-care, and mental health. These factors can vary in the degree to which they affect each patient. One patient may be mildly affected, only requiring minor alterations to lifestyle, while another patient may be so affected they require total care to function.

Congenital Abnormalities

A patient can suffer from impaired mobility due to a congenital abnormality. Congenital abnormalities are impairments of body function or structure present at birth (Table 1).

| Congenital Abnormality | Effects on Mobility |

|

Cerebral palsy |

|

|

Club foot |

|

|

Congenital heart defects |

|

|

Muscular dystrophy |

|

|

Spina bifida |

|

Muscle, Bone, and Joint Development

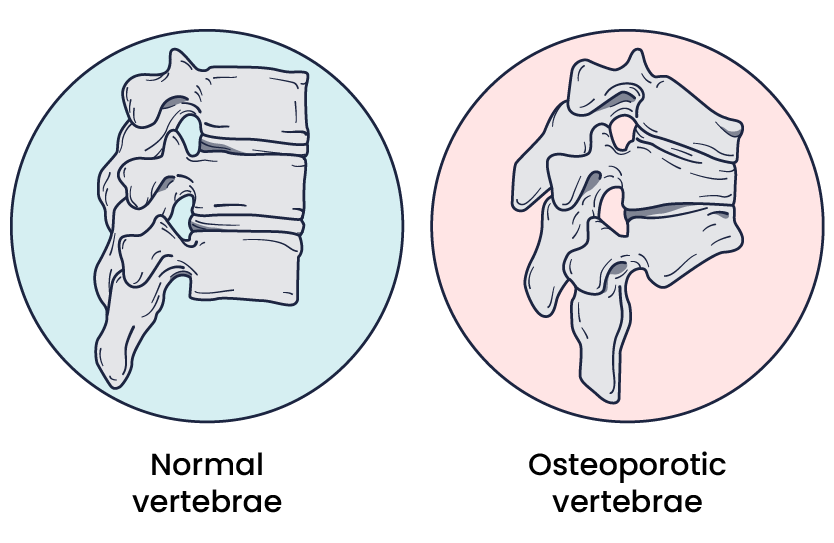

Joint structure, connective tissue, and changes in elasticity and flexibility of ligaments and tendons play a role in impaired mobility. As a patient ages, muscle is replaced with fibrous connective tissue and adipose tissue. Fibrous connective tissue protects, supports, and holds bones, muscles, organs, and other tissues within the body in place. Loss of bone mass begins to occur among individuals after the age of 40 (Campbell, 2021).

Osteoporosis is an age-related disorder that causes the gradual loss of bone density and strength. When the thoracic vertebrae are affected, there can be a gradual collapse of the vertebrae. This results in kyphosis, an excessive curvature of the thoracic region. Other factors that can impact mobility include excessive adipose bulk, which can impede range of motion (ROM); a lack of functional activities or exercises to promote flexibility and balance; and injury to muscle, joints, or connective tissues (Table 2).

| Muscle, Bone, Joint Disorders | Effects on Mobility |

| Osteoporosis | Progressive bone loss leads to decrease in bone strength. |

| Muscle loss | Ageing results in loss of muscle mass. |

| Increased fibrous connective tissue | Fibrous connective tissue protects, supports, and holds bones, muscles, organs, and other tissues. Ageing results in fibrous connective tissue replacing muscle mass. |

| Increased adipose tissue | Body fat begins to replace muscle mass in ageing. |

Fatigue and Stress

Fatigue often occurs secondary to physical or emotional stress from comorbidities, medication, poor nutrition, inactivity, or a substandard environment. A person experiencing fatigue for extended periods may see a decrease in normal activity patterns that results in decreased muscle strength and physical endurance. This physical decline in mobility impacts a person’s ability to carry out activities of daily living and therefore compromises their independence (Knoop et al, 2021).

External Factors

An external factor can also cause mobility issues. External factors are those that surround the patient and affect mobility, such as climate, terrain, housing design, neighbourhood safety, local laws, social attitudes, and support. Social determinants of health (SDOH) may also influence mobility. For example, a patient who lives on a street without sidewalks or with sidewalks that have been destroyed by tree roots and not maintained will not have the same access to walk as someone who lives on a street with maintained sidewalks. In assessing patients, nurses should ask questions about the patient’s social situations, their support systems, and access to resources that contribute to a healthy lifestyle.

Effects of Immobility

Immobility can pose a significant problem for all major body systems. Prolonged immobilisation can affect every organ system and result in complications, including increased morbidity and mortality, prolonged length of stay at facilities, and increased healthcare costs (Brennan, 2023). These complications can considerably affect a person’s quality of life and daily functioning. Immobility has negative effects on a patient’s psychological, cardiovascular, respiratory, gastrointestinal, metabolic, genitourinary, musculoskeletal, and integumentary functions.

Assessing Body Movement

When patients are unable to ambulate or have an injury to specific extremities, they are at risk of losing normal range of motion in joints. It is therefore important that assessment and movement of limbs/joints is performed to prevent complications such as contractures.

Assisting with Range of Motion

Range of motion (ROM) exercises are often prescribed through collaboration with the medical staff and physiotherapist. ROM exercises facilitate the movement of specific joints and promote mobility of the extremities. Because changes in joints can occur shortly after injury or periods of immobility, ROM exercises should be commenced as soon as possible.

A person’s range of motion (ROM) is the extent to which a part of the body can be moved around a joint or a fixed point. ROM is assessed during active ROM, active-assisted ROM, and passive ROM. Performing ROM exercises are undertaken in the same manner.

Active ROM is ROM that is done independently by the patient. Patients who can contract, control, and coordinate movement around a joint are able to participate in active ROM exercises. In active ROM exercise, the patient will demonstrate flexion, extension, hyperextension, or rotation of the associated joint independently without external assistance.

Active-assisted ROM is ROM performed with partial assistance from an external force; the patient is asked to perform ROM but additional assistance is provided if they encounter a point of difficulty, such as pain or weakness.

Passive range of motion ROM is movement to a joint or body part solely by another person or by a passive-motion machine. When the passive range of motion is applied, the joint of an individual receiving exercise is completely relaxed while the outside force moves the body part while they are lying in bed.

Things the nurse can assess while ROM exercises are performed include:

- Any onset of pain, including where or when the pain occurs

- Any restrictions to movement, and if there is a pattern

- If movement intensifies pain

- How the patient feels after ROM is complete.

With this assessment information, nurses can collaborate with the medical officer and physiotherapists to determine why any ROM deficits are occurring and create therapeutic interventions to support optimal ROM goals.

Posture and Gait

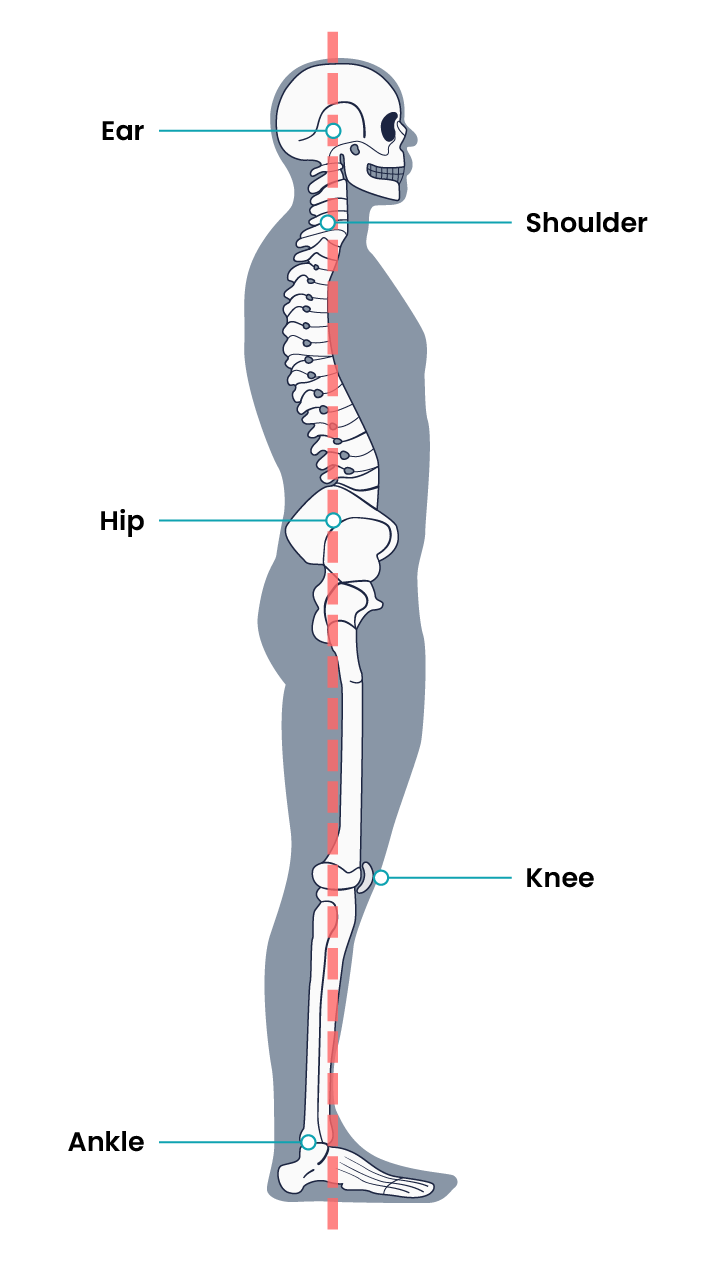

A person’s posture and the postural system are a fundamental mechanism to ensure balance against gravity, align the body, and assist in external environmental perception and action. Posture is not simply the act of “sitting up straight” but rather a central, dynamic process that relates to other physical processes such as sensory detection and coordination with the nervous system. A neutral posture is when a person’s upper trunk and head are at zero degrees in relation to the vertebral column. When a person stands the nurse should assess body alignment. This includes if the shoulders and hips are level: Do the toes point forward and is the spine straight or curved to either side? Take note if a slumped posture is present where the neck and/or shoulders are flexed forward, and the abdomen protrudes. If the patient’s posture deviates from a neutral position this could be due to deficiencies in postural control and postural orientation and can lead to damage and misalignment of vertebrae. Posture has a direct effect on the movements during gait.

The body’s gait is defined as a manner of walking or moving on foot. A person has a gait pattern – a series of rhythmical, alternating movements of the trunk and the limbs – that results in a forward progression. Generally, a person’s gait consists of a stance phase and a swing phase. Any pathological issue can affect this gait pattern, leading to abnormal gait patterns. Examples include joint deformities, muscle weakness, loss of motor function, and pain. Age and pregnancy can also affect gait with declines in walking speeds and changes in centres of gravity.

Assess gait by observing the patient’s stance phase and swing phase. When one leg is in the swing phase the other is in the stance phase. Through the stance phase, the heel should strike the ground and the ball of the foot takes the spread of body weight while the other heel pushes off and leaves the ground, this swing leg then moves forward in front of the body and the process continues. An example of this is provided in the video below. In these phases, different body positions help to propel a person forward. In observing the gait, take note of the patient’s posture, centre of gravity, and arm and leg movements. The patient’s posture should be neutral, with slight swaying in the standing position. A patient’s gait should be smooth and rhythmic, with their arms swinging at the sides.

Coordination and Balance

A person’s coordination is the organisation of different elements of the complex body, including muscular, skeletal, and sensory functions, that enable the elements to work together effectively. Evaluate coordination by having the patient rapidly touch each finger with the thumb, rapidly pat the hand on the thigh, and tap the foot on the floor (or against your hand, if the patient is supine). Repeat the sequence on the opposite limb. Normally, the movements would be coordinated. If the patient is unable to perform these movements, it may indicate disorder of the upper motor neurons or cerebellum.

The body’s balance is defined as a state of equilibrium. When a person’s centre of gravity falls outside its base of support (a stance with two feet evenly stable on the ground), they can become unstable. Proper coordination and balance are essential for gait stability and posture alignment. The Romberg test is commonly used to test balance. Ask the patient to stand with their feet together and eyes closed. Stand nearby and be prepared to assist if the patient begins to fall. It is expected that the patient will maintain balance and stand erect. A positive Romberg test occurs if the patient sways or is unable to maintain balance. The Romberg test is also a test of the body’s proprioception. Proprioception is the body’s ability to sense movement, action, and location of parts of the body. The sensations come from sensory receptors in the muscle, joints, and central nervous system signals to motor output. These sensory signals help patients perceive limb movements and positions, force, heaviness, and stiffness, and they help locate external objects relative to the body. A person’s vestibular function is their body’s ability to compensate in response to self and external forces and keep balance. If the vestibular system has any damage, it can affect balance, control of eye movements while the head is moving, and a sense of orientation to space. Finally, visual perception is a person’s ability to see and interpret the surrounding environment.

Strength

Posture, gait, coordination, and balance are all affected by strength, which is the quality or state of being strong. Strength is foundational for the body to dynamically adjust and compensate to achieve balance and stability, coordinate parts of the torso and limbs, enhance posture, and correct gait.

|

|

Lifespan consideration Adults lose muscle mass as they age and can be seen in even healthy adults from around the age of 30. By age 80 it can be expected up to 50% decrease in muscle strength (Marieb & Hoehn, 2023). Muscle mass declines because of a reduction in muscle fibres and fibre size. In addition, the ability of muscles to repair damage also decreases. This process occurs as someone ages because of fluctuations in hormones, including estrogen, testosterone, dehydroepiandrosterone, growth hormone, and insulin-like growth factor. Assessment of strength is important to establish a baseline for intervention evaluations.

|

Muscle strength should be equal bilaterally, and the patient should be able to fully resist an opposing force. Muscle strength varies among people depending on their activity level, genetic predisposition, lifestyle, and history. A common method of evaluating muscle strength is the Medical Research Council Manual Muscle Testing scale.

| Stage | Description |

| 0 | No muscle contraction |

| 1 | Trace muscle contraction, such as a twitch |

| 2 | Active movement only when gravity eliminated |

| 3 | Active movement against gravity but not against resistance |

| 4 | Active movement against gravity and some resistance |

| 5 | Active movement against gravity and examiner’s full resistance |

This method involves testing key muscles from the upper and lower extremities against gravity and the examiner’s resistance and grading the patient’s strength on a scale of 0 to 5. For example, to assess upper extremity strength, first begin by assessing bilateral hand grip strength. Extend your index and second fingers on each hand toward the patient and ask them to squeeze them as tightly as possible. Then, ask the patient to extend their arms with their palms up. As you provide resistance on their forearms, ask the patient to pull their arms toward them. Finally, ask the patient to place their palms against yours and press while you provide resistance.

Assessing Mobility Status and Need for Assistance

A patient’s mobility status and their need for assistance affect nursing care decisions, such as handling and transferring procedures, ambulation, and implementation of fall prevention activities. Initial mobility assessments are typically performed on admission to a facility and then updated if conditions change such as postoperatively. Initial assessments are generally undertaken by a physiotherapist (PT). As defined by the Clinical Excellence Commission, patients may be categorised into one of the following levels of assistance required:

In addition to the amount of assistance required, physiotherapists in consultation with medical staff may determine a patient’s weight-bearing status. For example, patients with lower extremity fractures or those recovering from knee or hip replacement often progress through stages of weight-bearing activity. Typical weight-bearing statuses are as follows.

Overall health status is considered in patients before mobilising to identify potential barriers to safe movement. Factors to consider include pain levels, cognitive function, vital signs, nutritional and hydration status. It is important to recognise that patients may have unrecognised physical deconditioning from the disease or injury that necessitated hospitalisation, or they may have developed new cognitive impairments related to the admitting diagnosis or their current medications. In addition to reviewing orders regarding weight-bearing status and required assistance, the nurse should perform an independent assessment of the patient’s abilities before undertaking any mobility or repositioning intervention.

Objective Mobility Screening Test

A Timed Up and Go Test begins by having the patient stand up from the chair or bed, walk three metres, turn around, walk back to the chair or bed, and sit down at their normal pace. The patient may use assistive devices if required. During the activity, the nurse takes note of the posture, gait, stride length, and balance. The activity is timed, patients taking longer than 12 seconds to complete are considered a high risk of falling. The assessment does not provide guidance on what the nurse should do if the patient cannot maintain seated balance, weight-bear, or stand and walk. Therefore, there are limitations on its use in the acute care setting.

Link to Learning

Watch a demonstration of the Timed up and go Test [1:29]:

The Banner Mobility Assessment Tool (BMAT) was developed to provide guidance regarding safe patient handling and mobility (SPHM). It is used as a nurse-driven bedside assessment of patient mobility and walks the patient through a four-step functional task list that identifies the mobility level the patient can achieve. It then provides guidance regarding the SPHM technology needed to safely transfer and mobilise the patient.

Links to Learning

- View the Banner Mobility Assessment Tool 2.0 for Nurses.

- Watch the instructional video on how to complete a mobility assessment using the BMAT [4:35]:

Assisting Mobility – Safe Patient Handling

Patient handling comes with risk to both patients and healthcare workers. Healthcare workers need to take precautions to reduce risk to themselves and patients through correct manual handling techniques. No lift policies are common in Australian healthcare facilities, these recommend no healthcare worker fully lifts a person, with the exception of small children, without the assistance of mechanical aids, devices, or other healthcare workers (Worksafe, 2017).

To reduce the risk of injury the healthcare worker should undertake the following before movement:

- Perform a risk assessment of the patient to be mobilised. Consider the patient’s weight, size, strength, balance, medical condition, level of consciousness, behaviour predictability, willingness to assist and ability to communicate/understand.

- Perform a risk assessment of the environment ensuring adequate lighting, non-slip floors, handrails and obstacle-free paths

- Have awareness of attached medical devices such as intravenous therapy, indwelling catheters and drains

- Maximise opportunity for the patient to assist in movement through education and supply of assistive devices

- Be well educated in the correct use of assistive devices

- Ensure ease of access to assistive devices

- Apply proper body mechanics throughout the procedure. (Worksafe, 2017)

Assistive Devices

There are several types of assistive devices that a nurse may incorporate during safe patient handling and mobility. An assistive device is an object or piece of equipment designed specifically to help a patient with activities of daily living. These can be broken into two categories:

- Ambulatory assistive devices: Walking cane/stick, wheeled walkers/frames, crutches, wheelchairs, electronic kneel scooters.

- Manual handling tools: Walk belts, slide boards, Slide sheets, mechanical lifting devices.

Ambulatory Assistive Devices

Crutches

Crutches are an aid used for standing, walking, and mobility for patients who cannot support the weight of their bodies with their leg, knee, or ankle. The patient’s weight-bearing status will determine how much pressure can be put on the affected limb. There are three types of crutches: axilla, forearm, and gutter. Sizing equipment accurately and educating in the correct usage is an important aspect of patient safety.

Axillary (underarm) crutch should be two fingers distant between the axilla and axilla pad of the crutch. The patient’s weight should be focused where their hands grip the crutch and not under their armpits. This is to prevent axillary nerve damage.

Forearm (Canadian) crutches have a forearm cuff and handgrip. These are often used long-term in patients with lower extremity disabilities.

Gutter crutches are modified forearm crutches and a modified hand grip for patients who may not have mobility and strength in their hands. This type of crutch can be recommended for patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Crutches should be tailored to the patient and fit according to their height.

Link to Learning

The following links to learning provide guides on using axillary, forearm, and gutter crutches:

- How to Walk with Crutches includes sizing and different gait techniques for axillary crutches [3:29]

- How to Use Forearm Crutches demonstrates how to safely and properly use forearm crutches [2:39]

- The gutter crutches demonstration below shows patients ambulating using gutter crutches [1:20]:

Knee walkers (knee scooters or mobility scooters) are used as well to help with lower limb mobility. This wheeled crutch alternative allows the injured foot and/or leg to be elevated on a padded platform. The patient can balance naturally on two legs and can move by pushing with the good leg and steering with the handlebar.

Link to Learning

This knee walker demonstration shows how to adjust and use a knee walker [1:29]:

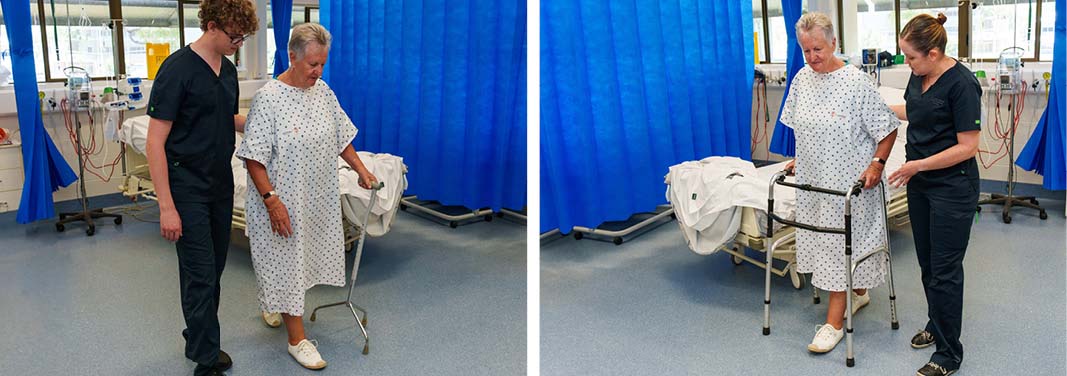

Walker and Walking Stick

A walker is an aide that has four points of contact with the ground. Walkers provide a greater base of support, assisting in stability for balance and mobility. There are many types of walkers including standard, two-wheeled, upright, and four-wheeled walkers. Standard four-point walkers (four-point or Zimmer frame) are used with the patient taking one step forward and then the patient moving into the walker. Two-wheeled walkers are used the same way except the walker can slide forward instead of the patient needing to pick it up because there are two front wheels. Four-wheeled walkers have handles to control brakes and may also have a seat, tray, or basket. The patient must remember to lock the brakes when stationary to avoid the risk of a fall. The gutter frame walkers are wheeled and adapted to patients who need more support. Forearm supports fix the elbows at 90 degrees.

A walking stick is a singular assistive device that assists in balance when walking or helps compensate for an injury or disability. A walking stick can either have a single tip or four points that touch the ground, called a four-pronged stick. The four-pronged stick provides a broader base of support. The grip on walking sticks can vary by size and material. Some may be made of foam or plastic, and sizes may vary for arthritic hands. The patient’s elbow bend and wrist height should be taken into consideration when fitting a walking stick for a patient. The elbow should bend at a comfortable angle, approximately 15 degrees, and the top of the walking stick should line up with the crease on the patient’s wrist. Patients should hold the walking stick in the opposite hand of the weak or painful limb. The walking stick should move with the affected leg.

Manual Handling Assistive Devices

Walk Belts

Walk belts should be used to ensure stability when assisting patients to stand, ambulate, or transfer from bed to chair. Walk belts will vary in appearance and come in various sizes to appropriately suit the patient. It may or may not have handles. It is placed around a patient’s waist and fastened with velcro or buckle. The walk belt should be applied on top of clothing or a gown to protect the patient’s skin.

Link to Learning

How to apply a walk belt [1:52]

How to hold a walk belt [1:47].

Patient Transfer Boards

A patient transfer board, commonly called a slide board, is used to transfer mobility-restricted patients from one surface to another. Slide boards are available in different sizes that are selected for the purpose of transfer. A small transfer board may be utilised to assist a patient slide from one seated position to another such as chair to wheelchair. A larger full-length board may be used to slide a patient from a laying position to another laying position such as a stretcher to bed.

Slide Sheets

Specifically designed sheets that will slide smoothly aiding the transfer of patients without the need to lift. The sheets are commonly used in conjunction with slide boards or used independently to reposition the patient in the bed.

Manual Handling – Mechanical Lifting Devices

Various lifting devices, (commonly referred to as a hoist), are available to assist patients who weigh more than 20 kgs and who cannot assist in moving or transferring themselves (Worksafe, 2017). Devices include: mobile floor-based lifting device, ceiling-mounted lifting device, sit-to-stand lifts and lifting frames. Air-assisted lifting devices are also available.

The lifting device will contain a main hoisting frame and often have several attachments that assist achieve the movement required. This may include hoisting slings to move the fully dependent person from one area to another such as bed to chair, or lifting frames (commonly referred to as a Jordan frame) to lift the patient in a lying position from a surface while specific care is carried out. There are many different brands and styles of devices. Healthcare workers should be fully trained in the use of the devices utilised in the facility where they are working and ensure they follow manufacturer instructions. Healthcare workers should ensure that they only use genuine attachments designed for the specific hoist they are using.

Hoisting Sling

A hoisting sling is used to move patients who cannot bear weight or have a medical condition that does not allow them to stand or assist with moving. The hoisting sling will attach to the lifting hoist which may be a portable device or permanently attached to the ceiling. The sling may be utilised to lift a patient from the floor, bed, or chair in either sitting or lying position.

Sit-to-Stand Lifts

Sit-to-stand lifts (commonly referred to as standing hoists) are mobility devices that assist weight-bearing patients who are unable to transition from a sitting position to a standing position using their own strength. They are used to safely transfer patients who have some muscular strength but not enough strength to safely change positions by themselves.

Patient Positioning

Repositioning an immobile patient maintains body alignment and prevents pressure injuries, foot drop, and contractures. Proper positioning also provides comfort for patients who have decreased mobility related to a medical condition or treatment. When repositioning a patient in bed, supportive devices such as pillows, rolls, and blankets can aid in providing comfort and safety. There are several potential positions that may be used based on the patient’s medical condition, preferences, or treatment related to an illness. It is important to reposition patient appropriately to prevent neurological injuries that can occur, such as if a patient is inadvertently positioned on their arm.

Patient Positions in Bed

|

When positioning the patient, careful consideration should be given to potential pressure injury development. Protective booties, a heel wedge or protective dressings on pressure points, such as the heels, elbows or sacrum, can be used to prevent pressure injuries in patients who have restricted movement or are immobile. |

Transfer Techniques

First, determine the level of assistance needed to provide optimal patient care. It is vital to prevent friction and shear when moving a patient up in bed to prevent pressure injuries. If a patient is unable to assist with repositioning in bed, follow agency policy regarding using lifting devices and mechanical lifts. If the patient can assist with repositioning and minimal lifting by carers is required, use the following guidelines.

Falls Prevention

Seventy-seven percent of hospitalisations related to injury are caused by falls (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [AIHW], 2022). Falls may occur for many reasons and in any age group however, the prevalence is higher in the older population. In Australia, the definition of ‘older person’ is 65+ for the non-indigenous population and 50+ for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples (Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care [ACSQHC], 2024). A fall in this age group is more likely to see hospitalisation or death as a result (AIHW, 2023). In response to these facts, the ACSQHC developed a series of fall guidelines for Australian hospitals, residential care facilities and community care titled Preventing falls and Harm from falls in older people: Best practice guidelines (ACSQHC, 2009).

Resulting in increased length of stay, loss of independence and sometimes death, falls are a major concern in hospitals (ACSQHC 2024). This chapter will look at falls prevention of the hospitalised patient. For further information on residential and community care refer to the guidelines mentioned above.

Best practice approach for preventing falls in hospitals includes four key components:

- Identification of falls risk

- Implementation of standard falls prevention strategies

- Implementation of interventions targeting these risks to prevent falls

- Prevention of injury to those people who do fall.

Identification of Falls Risk Factors

Understanding why an individual may be at risk of a fall allows the nurse to personalise care plans and implement appropriate targeted interventions. Risk factors for falls can be influenced by both intrinsic and extrinsic factors.

|

|

Intrinsic Factors Older people, people with a cognitive or mobility disability, and those with a history of previous falls are considered at risk. Other contributing factors that increase risk include: poor vision, cognitive impairment such as confusion, disorientation, impaired memory or judgement, postural instability or muscle weakness, postural hypotension, urinary frequency or incontinence, and current medication regime. |

|

Extrinsic Factors Extended periods of hospitalisation, the environment in which care is provided and the time of day can all contribute to increased falls risk (ACSQHC 2024). |

Implementing Standard Falls Prevention Strategies in the Acute Care Setting

Falls Prevention Strategies – Standard

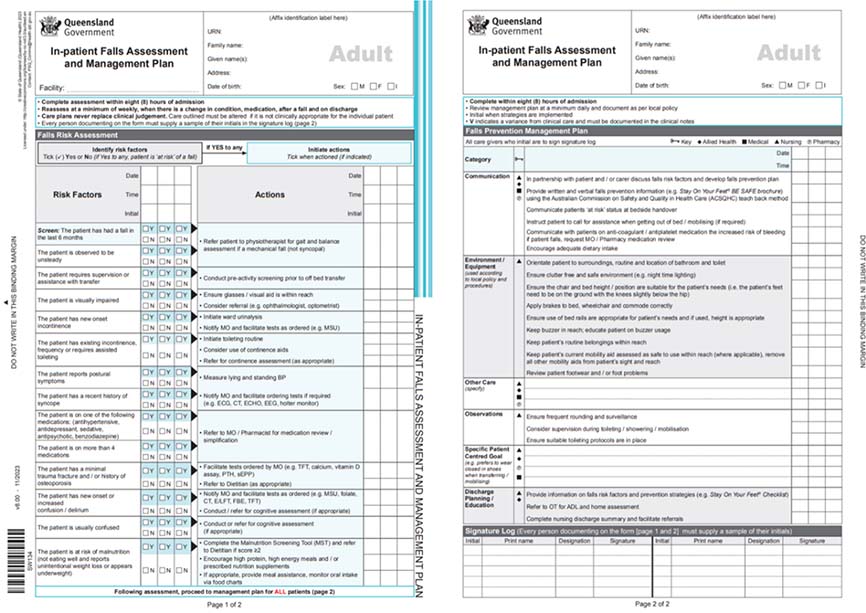

Standard practices should be applied to all persons at risk of falls. The first recommendation of standard falls prevention practices is that all patients are screened on admission to hospital and those considered at-risk groups have a falls assessment and management plan implemented. It is recommended that healthcare facilities utilise validated falls assessment and management plan tools to screen and assess patients (ACSQHC, 2009). These tools vary from state to state but overall the purpose remains the same. One such example is the In patient falls assessment and management plan developed by the Queensland Government for use in Queensland Health facilities.

In general, the frequency of screening will be dependent on the facility in which the patient is entering, and local policy should be followed. Typically, at a minimum, all patients considered at risk are assessed on entry and then repeated weekly or when there is a change in condition, medication, following a fall, and/or on discharge. Falls management plans should be reviewed daily at a minimum while a patient is receiving care in hospital. Other standard falls prevention strategies include:

- Communicate clearly at bedside handover a patient’s falls risk status

- Orientate patient and family to the environment, including bathroom and toilet

- Educate patient and family regarding falls risks and falls prevention strategies

- Inform patient and family of ward routines, mealtimes, and buzzers

- Ensure environment is clutter free, safe and has adequate lighting

- Ensure bed heights and chairs are suitable for the patients’ needs

- Apply brakes on beds, wheelchairs, and commodes

- Bed rails should be used with caution and at appropriate height according to the patient needs

- Ensure buzzer is within easy reach of patient

- Ensure patient can reach personal belongings with ease

- Mobility aids should be kept within reach

- Footwear should be well-fitting and non-slip

- Frequent rounding should be attended.

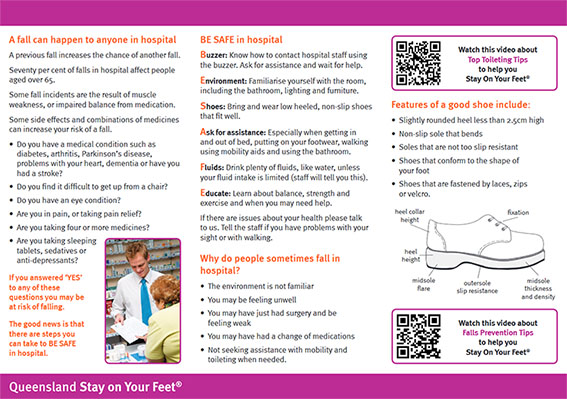

BE SAFE (Buzzer, Environment, Shoes, Ask, Fluids and Educate)

Educating and keeping patients well-informed about their care is a key strategy in falls prevention. As part of a Queensland Government initiative, ‘Stay on Your Feet QLD’, all at-risk patients should be provided a Stay on your feet BE SAFE patient brochure on entry to healthcare. BE SAFE advises the patient to BUZZ for assistance and wait for help. Ensure they familiarise themselves with the unit ENVIRONMENT in which they are admitted. Wear low-heeled, non-slip SHOES that fit well. ASK for assistance, especially when getting out of bed. Drink plenty of FLUIDS unless contraindicated, and EDUCATE yourself on balance, strength, and exercise.

Falls Prevention Strategies – Targeted

Targeted practices will be triggered by the person’s risk factors identified in the falls assessment. The following table identifies risk factors and suggests additional actions to take to reduce the likelihood of a fall occurring.

Prevention of Injury to those People who do Fall

Unfortunately, despite fall prevention strategies and programs in place, falls do, on occasion, still occur. The ACSQHC (2024) recommends practices be established that will assist in mitigating harm caused by falls in high-risk patients. The registered nurse should familiarise themselves with policy within their facility if a fall were to occur. Considerations for high-risk falls patients include:

Hip protector: Consider hip protectors for older patients who are known to have frequent falls, osteoporosis, or low body mass index.

Vitamin D and Calcium: Consider the use of Vitamin D and Calcium to increase muscle strength and maintain bone density.

Osteoporosis: Consider bone mineral density (BMD) in the likelihood of fractures occurring during falls. Refer for BMD testing. Incorporate strategies that strengthen and protect bone from injury. Review medicines associated with osteoporosis risk.

The Falling Patient

If you are witness to a patient fall while ambulating or while transferring a patient from one surface to another, it is recommended that you do not attempt to stop the fall or catch the patient because this risks injury to yourself. Instead, attempt to control the fall by lowering the patient to the floor. When the patient starts to fall, if able, move behind the patient and take one step back. Support the patient around the waist or hip area or grab the walk belt. Bend one leg and place it between the patient’s legs. Slowly slide the patient down your leg, lowering yourself to the floor at the same time. Always protect the head first. Once the patient is on the floor, utilise the steps below in post-fall management.

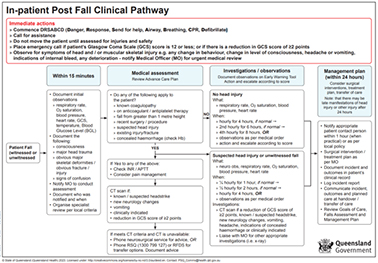

Post-Fall Management

Actions taken immediately following a fall should be aimed at reducing harm. Immediate action is to assess using DRABCD (Danger, Response, Airway, Breathing, CPR, Defibrillate). Call for the assistance of a second person if there is no indication for resuscitation. A medical emergency call should be activated if the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) is altered from previous assessments or resuscitation is required. It is recommended to not move the patient until injury assessment is complete. Observe closely for head injury and/or musculoskeletal injury and notify a medical officer for review.

The following In-patient post fall clinical pathway is an example of a procedure recommended post-fall.

Key Takeaways

- Mobility refers to the capacity to alter and manage body position. It necessitates muscle strength, energy, skeletal stability, joint function, and neuromuscular coordination.

- Mobility, including the movement of extremities, changing positions, sitting, standing, and walking, is essential for preventing the degradation of various body systems and avoiding complications associated with immobility.

- Immobility can adversely affect psychological, cardiovascular, respiratory, gastrointestinal, metabolic, genitourinary, musculoskeletal, and integumentary functions.

- Factors influencing mobility can be internal, such as physiological, psychological, or spiritual aspects, or external, including climate, terrain, and social attitudes.

- Proper patient positioning is essential for maintaining body alignment and preventing pressure injuries and contractures. Common positions include the supine, prone, lateral, Sims, Fowler’s, semi-Fowler’s, Trendelenburg, and tripod positions.

- Evaluating mobility status and the requirement for assistance is crucial for ensuring safe handling, transfers, ambulation, and fall prevention for both nurses and patients. Assessments encompass a range of motion, posture, gait, coordination, balance, and strength. Other factors to consider include pain levels, cognitive function, vital signs, nutritional and hydration status, use of assistive devices, and environmental safety.

- Nurses utilise various interventions to promote mobility and movement. These include range of motion exercises, assisting patients with walking or repositioning, and encouraging the use of assistive devices.

- The best practice approach for preventing falls in hospitals includes four key components: implementing standard falls prevention strategies, identifying fall risks, applying interventions targeting these risks to prevent falls, and preventing injury in individuals who do fall.

References

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. (2009). Preventing falls and harm from falls in older people: Best practice guidelines for Australian hospitals 2009. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/sites/default/files/migrated/30459-HOSP-Guidebook.pdf

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. (2024). Preventing falls and harm from falls in older people: Best practice guidelines for Australian hospitals [Draft]. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/sites/default/files/2024-10/falls-guidelines-hospitals-draft.pdf

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2022). Falls in older Australians aged 65 and over, 2019-20. Australian Government. https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/467fd7e8-bb5d-46b0-890d-c7235591804b/aihw-injcat-226-fact-sheet.pdf.aspx

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2023). Falls. Australian Government. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/injury/falls

Brennan, M. M. (2023). Movement is muscle in hospitalized adults. Geriatric Nursing, 55(Jan-Feb), 373-375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2023.11.015

Campbell, B. J. (2021). Healthy bones at every age. OrthoInfo. https://orthoinfo.aaos.org/en/staying-healthy/healthy-bones-at-every-age/

Clinical Excellence Commission. (2018). Standardised mobility terminology, a guide for use across NSW. https://www.cec.health.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/452809/Final-Standardised-Mobility-Terminology-Guide-for-Use-Across-NSW.pdf

Gyasi, R. M., Asante, F., Hambali, M. G., Odei, J., Jacob, L., Obeng, B., Peprah, P., Asamoah, E., Agyemang-Duah, W., Abass, K., Asiki, G., & Adam, A. M. (2023). Mobility limitations and emotional dysfunction in old age: The moderating effects of physical activity and social ties. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 38(7), e5969. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.5969

Knoop, V., Cloots, B., Costenoble, A., Debain, A., Vella Azzopardi, R., Vermeiren, S., Jansen, B., Scafoglieri, A., Bautmans, I., & Gerontopole Brussels Study group. (2021). Fatigue and the prediction of negative health outcomes: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Ageing Research Reviews, 67, 101261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2021.101261

Marieb, E.N., & Hoehn, K. (2023) Human anatomy & physiology, global edition (12th ed). Pearson.

Worksafe. (2017). People handling. https://www.worksafe.qld.gov.au/safety-and-prevention/hazards/hazardous-manual-tasks/guidance-for-high-risk-industries/people-handling

Chapter Attribution

This chapter has been adapted in parts from:

Clinical nursing skills (2024) by Christie Bowen et al., OpenStax, is used under a CC BY licence.

Nursing fundamentals 2e (n.d.) by Open Resources for Nursing, Chippewa Valley Technical College is used under a CC BY licence.

Media Attributions

- Osteoporotic Vertebrae © J. Gordon Betts, Kelly A. Young, James A. Wise, Eddie Johnson, Brandon Poe, Dean H. Kruse, Oksana Korol, Jody E. Johnson, Mark Womble & Peter DeSaix adapted by Eileen Siddins is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Neutral Spine Posture © Eileen Siddins is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Romberg Test © Ben Green is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Strength Tests © Ben Green is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Walker Examples © OpenStax (left) and DirkvdM (right) adapted by Christy Bowen (B) is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Walker Examples © Ben Green is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Walk Belt © Ben Green is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Transfer Using Sheet and Board © Ben Green is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Mechanical Lifting Device © Ben Green is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- In-Patient Falls Form © Queensland Health

- BE SAFE Brochure © State of Queensland (Department of Health) is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Hip Protector © Queensland Health is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- Lowering Patient © Ben Green is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- In-patient Fall Clinical Pathway Flowchart © State of Queensland (Queensland Health) is licensed under a CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution NonCommercial NoDerivatives) license

Connective tissue in which fat is stored

The extent to which a part of the body can be moved around a joint or a fixed point

Socioeconomic factor such as poverty, employment, and education that may impact on health outcomes, mobility, education, and environmental conditions. Individuals with health-related social needs may lack affordable housing, access to healthy foods, connections with social services, or adequate transportation

A belt, with or without handles, that is fastened around a patient’s waist used to ensure stability when assisting patients to stand, ambulate, or to transfer from bed to chair