Assessing and Supporting Nutrition

Amy McCrystal; Leisa Sanderson; and Jessica Best

Learning Outcomes

In this chapter you will learn how to:

- Describe the structure and function of the gastrointestinal/digestive system and identify the essential nutrients that are required for growth, energy and bodily processes

- Recognise various risk factors that can impact an individual’s nutritional status

- Develop the skills necessary to assess an individual’s nutritional status utilising the ABCDE (Anthropometric, Biochemical, Clinical, Dietary, and Environmental) approach, including the ability to calculate body mass index (BMI)

- Explain the different options available for nutritional support, including oral, enteral, and parenteral nutrition, and their indications and applications in clinical practice

- Identify and apply nursing interventions that can effectively improve an individual’s nutritional status, considering personalised care and patient education.

Introduction

|

Good nutrition is essential for a healthy life, providing the necessary substances to sustain life, support growth, and maintain bodily functions. Adequate nutrition plays a crucial role in overall health by preventing and treating diseases, promoting normal growth, maintaining a healthy weight, enhancing resistance to infection, and protecting against chronic diseases and premature death (National Health and Medical Research Council [NHMRC], 2013). According to the NHMRC (2013), diet is one of the most important modifiable risk factors for health. Nurses play a vital role in promoting healthy nutrition to prevent disease, assist recovery from illness and surgery, and manage chronic illnesses with healthy food choices. Healthy nutrition helps prevent obesity and chronic diseases like diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Nurses encourage healthy eating habits, knowing it is easier to maintain health than to regain it after disease onset. They also promote good nutrition during recovery, even when patients have poor appetites or nausea. For chronic diseases, nurses educate patients on prescribed diets, such as low carbohydrate for diabetes or low fat, salt, and cholesterol for cardiovascular disease. Nurses advocate for patients with nutritional deficits, identifying issues like difficulty swallowing and making appropriate referrals. They also administer alternative nutrition forms, such as enteral or parenteral feedings. This chapter will cover the nutritional requirements for good health, factors affecting nutritional status, and nutritional assessments and interventions. |

Nutrition

Digestive System

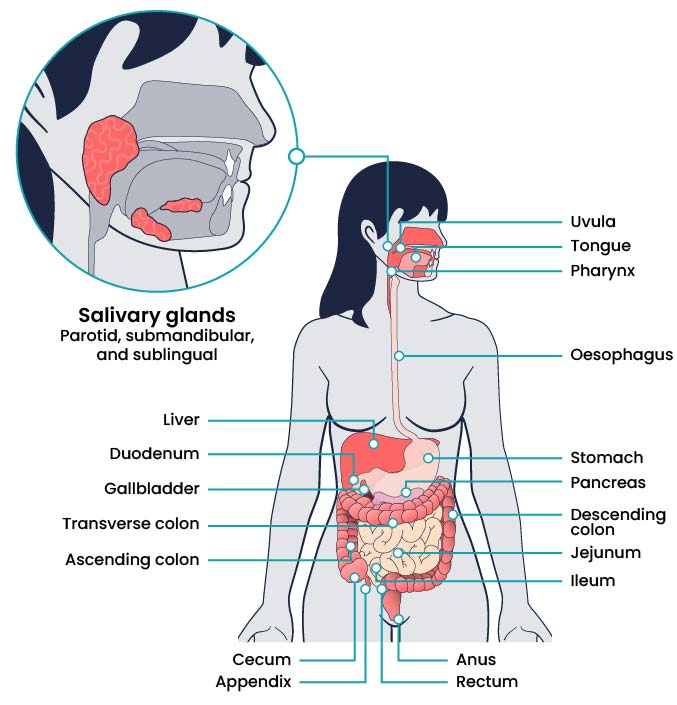

Before exploring good nutrition and discussing assessments and interventions, it is important to review the structure and function of the digestive system and the role it plays in breaking down food, absorbing nutrients, and eliminating waste.

The digestive system breaks down food and then absorbs nutrients into the bloodstream via the small intestine and large intestine. Good health depends on good nutrition, therefore any disorder affecting the functioning of the digestive system can significantly impact overall health and well-being and increase the risk of chronic health conditions.

Structure and Function

The gastrointestinal system (also referred to as the digestive system) is responsible for several functions, including digestion, absorption, and immune response. Digestion begins in the upper gastrointestinal tract at the mouth where chewing of food occurs. This is called mastication. Mastication results in mechanical digestion when food is broken down into small chunks and swallowed. Masticated food is formed into a bolus as it moves toward the pharynx in the back of the throat and then into the oesophagus. Coordinated muscle movements in the oesophagus called peristalsis move the food bolus into the stomach where it is mixed with acidic gastric juices and further broken down into chyme through a chemical digestion process. As chyme is moved out of the stomach and into the duodenum of the small intestine, it is mixed with bile from the gallbladder and pancreatic enzymes from the pancreas for further digestion (LibreTexts, 2024).

Absorption is a second gastrointestinal function. After chyme enters the small intestine, it comes into contact with tiny finger-like projections along the inside of the intestine called villi. Villi increase the surface area of the small intestine and allow nutrients, such as protein, carbohydrates, fat, vitamins, and minerals, to absorb through the intestinal wall and into the bloodstream. Absorption of nutrients is essential for metabolism to occur because nutrients fuel bodily functions and create energy. Peristalsis moves leftover liquid from the small intestine into the large intestine, where additional water and minerals are absorbed. Waste products are condensed into faeces and excreted from the body through the anus (LibreTexts, 2024). See Figure 1 for labelled parts of the gastrointestinal system.

In addition to digestion and absorption, the gastrointestinal system is also involved in immune function. Good bacteria in the stomach create a person’s gut biome. Gut biome contributes to a person’s immune response through antibody production in response to foreign materials, chemicals, bacteria, and other substances (Keeton & Hightower, 2025). For example, clients may develop Clostridium difficile (C-diff) after taking antibiotics that kill these beneficial bacteria in the gut.

Essential Nutrients

Nutrients from food and fluids are used by the body for growth, energy, and bodily processes. Essential nutrients refer to nutrients that are necessary for bodily functions but must come from dietary intake because the body is unable to synthesise them. Essential nutrients include vitamins, minerals, some amino acids, and some fatty acids (Youdim, 2019). Essential nutrients can be further divided into macronutrients and micronutrients.

Macronutrients

Macronutrients make up most of a person’s diet and provide energy, as well as essential nutrient intake. Macronutrients include carbohydrates, proteins, and fats. However, too many macronutrients without associated physical activity cause excess nutrition that can lead to obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, kidney disease, and other chronic diseases. Too few macronutrients result in undernutrition, which contributes to nutrient deficiencies and malnourishment (Youdim, 2019).

Carbohydrates

Carbohydrates are sugars and starches and are an important energy source that provides 17 kJ per gram of energy. Simple carbohydrates are small molecules (called monosaccharides or disaccharides) and break down quickly. As a result, simple carbohydrates are easily digested and absorbed into the bloodstream, so they raise blood glucose levels quickly. Examples of simple carbohydrates include table sugar, syrup, and fruit juice. Complex carbohydrates are larger molecules (called polysaccharides) that break down more slowly, which causes slower release into the bloodstream and a slower increase in blood sugar over a longer period of time. Examples of complex carbohydrates include whole grains, beans, and vegetables (Youdim, 2019).

Foods can also be categorised according to their glycemic index, a measure of how quickly glucose levels increase in the bloodstream after carbohydrates are consumed. The glycemic index was initially introduced as a way for people with diabetes mellitus to control their blood glucose levels. For example, processed foods, white bread, white rice, and white potatoes have a high glycemic index. They quickly raise blood glucose levels after being consumed and also cause the release of insulin, which can result in more hunger and overeating. However, foods such as fruit, green leafy vegetables, raw carrots, kidney beans, chickpeas, lentils, and bran breakfast cereals have a low glycemic index. These foods minimise blood sugar spikes and insulin release after eating, which leads to less hunger and overeating. Eating a diet of low glycemic foods has been linked to a decreased risk of obesity and diabetes mellitus (Youdim, 2019). See Figure 2 for an image of the glycemic index of various foods.

Proteins

Proteins are peptides and amino acids that provide 17kJ/g of energy. Proteins are necessary for tissue repair and function, growth, energy, fluid balance, clotting, and the production of white blood cells. Protein status is also referred to as nitrogen balance. Nitrogen is consumed in dietary intake and excreted in the urine and faeces. If the body excretes more nitrogen than it takes in through the diet, this is referred to as a negative nitrogen balance. Negative nitrogen balance is seen in clients with starvation or severe infection. Conversely, if the body takes in more nitrogen through the diet than what is excreted, this is referred to as a positive nitrogen balance (Youdim, 2019). During positive nitrogen balance, excess protein is converted to fat tissue for storage.

Proteins are classified as complete, incomplete, or partially complete. Complete proteins must be ingested in the diet. They have enough amino acids to perform necessary bodily functions, such as growth and tissue maintenance. Examples of foods containing complete proteins are soy, quinoa, eggs, fish, meat, and dairy products. Incomplete proteins do not contain enough amino acids to sustain life. Examples of incomplete proteins include most plants, such as beans, peanut butter, seeds, grains, and grain products. Incomplete proteins must be combined with other types of proteins to add to amino acids and form complete protein combinations (Brazier, 2020). For example, vegetarians must be careful to eat complementary proteins, such as grains and legumes, or nuts and seeds, to create complete protein combinations during their daily food intake. Partially complete proteins have enough amino acids to sustain life, but not enough for tissue growth and maintenance. Because of the similarities, most sources consider partially complete proteins to be in the same category as incomplete proteins. See Figure 3 for an image of protein-rich foods.

Fats

Fats consist of fatty acids and glycerol and are essential for tissue growth, insulation, energy, energy storage, and hormone production. Fats provide 38kJ/g of energy (Youdim, 2019). While some fat intake is necessary for energy and uptake of fat-soluble vitamins, excess fat intake contributes to heart disease and obesity.

Fats are classified as saturated, unsaturated, and trans fatty acids. Saturated fats come from animal products, such as butter and red meat (e.g., steak). Saturated fats are solid at room temperature. Recommended intake of saturated fats is less than 10% of daily calories because saturated fat raises cholesterol and contributes to heart disease (Healthwise, 2020).

Unsaturated fats come from oils and plants, although chicken and fish also contain some unsaturated fats. Unsaturated fats are healthier than saturated fats. Examples of unsaturated fats include olive oil, canola oil, avocados, almonds, and pumpkin seeds. Fats containing omega-3 fatty acids are considered polyunsaturated fats and help lower LDL cholesterol levels. Fish and other seafood are excellent sources of omega-3 fatty acids.

Trans fats are fats that have been altered through a hydrogenation process, so they are not in their natural state. During the hydrogenation process, fat is changed to make it harder at room temperature and have a longer shelf life. Trans fats are found in processed foods, such as chips, crackers, and cookies, as well as in some margarines and salad dressings. Minimal trans-fat intake is recommended because it increases cholesterol and contributes to heart disease (Healthwise, 2020).

Micronutrients

Micronutrients include vitamins and minerals.

Vitamins

Vitamins are necessary for many bodily functions, including growth, development, healing, vision, and reproduction. Most vitamins are considered essential because they are not manufactured by the body and must be ingested in the diet. Vitamin D is also manufactured through exposure to sunlight (Johnson, 2022).

Vitamin toxicity can be caused by overconsumption of certain vitamins, such as vitamins A, D, C, B6, and niacin. Conversely, vitamin deficiencies can be caused by various factors, including poor food intake due to poverty, malabsorption problems with the gastrointestinal tract, drug and alcohol abuse, proton pump inhibitors, and prolonged parenteral nutrition. Deficiencies can take years to develop, so it is often a long-term problem for people (Johnson, 2022).

Vitamins are classified as water soluble or fat soluble. Water-soluble vitamins are not stored in the body and include vitamin C and B-complex vitamins: B1 (thiamine), B2 (riboflavin), B3 (niacin), B6 (pyridoxine), B12 (cyanocobalamin), and B9 (folic acid). Additional water-soluble vitamins include biotin and pantothenic acid. Excess amounts of these vitamins are excreted through the kidneys in urine, so toxicity is rarely an issue, though excess intake of vitamin B6, C, or niacin can result in toxicity (Healthwise, 2020). See below for a list of selected water-soluble vitamins, their sources, and their function.

Fat-soluble vitamins are absorbed with fats in the diet and include vitamins A, D, E, and K. They are stored in fat tissue and can build up in the liver. They are not excreted easily by the kidneys due to storage in fatty tissue and the liver, so overconsumption can cause toxicity, especially with vitamins A and D (Healthwise, 2020). See below for a list of selected fat-soluble vitamins, their sources, their function, and manifestations of deficiencies and toxicities.

Minerals

Minerals are inorganic materials essential for hormone and enzyme production, as well as for bone, muscle, neurological, and cardiac function. Minerals are needed in varying amounts and are obtained from a well-rounded diet. In some cases of deficiencies, mineral supplements may be prescribed by a health care provider. Deficiencies can be caused by malnutrition, malabsorption, or certain medications, such as diuretics.

Minerals are classified as either macrominerals or trace minerals. Macrominerals are needed in larger amounts and are typically measured in milligrams, grams, or milliequivalents. Macrominerals include sodium, potassium, calcium, magnesium, chloride, and phosphorus.

Trace minerals are needed in tiny amounts. Trace minerals include zinc, iron, chromium, copper, fluorine, iodine, manganese, molybdenum, and selenium (US National Library of Medicine, 2024). See below for a list of selected macrominerals and trace minerals.

Dietary Guidelines

The Australian Dietary Guidelines produced by the NHMRC offer advice about the amount and kinds of foods required to eat for health and well-being and give several recommendations for adults to maintain good health. The guidelines emphasise enjoying a wide variety of nutritious foods from the five food groups daily. The groups include:

- Vegetables of different types and colours, and legumes/beans

- Fruit

- Grain (cereal) foods, mostly wholegrain and/or high cereal fibre varieties, such as breads, cereals, rice, pasta, noodles, polenta, couscous, oats, quinoa, and barley

- Lean meats and poultry, fish, eggs, tofu, nuts and seeds, and legumes/beans

- Milk, yoghurt, cheese and/or alternatives, mostly reduced fat.

Further advice is to drink plenty of water and limit the intake of foods containing saturated fat, added salt, added sugars, and alcohol.

To achieve and maintain a healthy weight, a person needs to be physically active and choose nutritious foods and drinks that meet energy needs. Maintaining a healthy weight requires a diet in which nutrient requirements are met and total energy intake does not often exceed total energy expenditure (NHMRC, 2013).

Link to Learning

Read the Eat For Health Australian Dietary Guidelines summary from the National Health and Medical Research Council (2013) for further insight into evidence-based advice on dietary requirements.

Factors Affecting Nutrition

Many factors can cause altered nutrition, such as physiological factors, cultural and religious beliefs, economic resources, drug and nutrient disorders, surgery, altered metabolic states, alcohol and drug abuse, and psychological states.

Lifespan Considerations

|

Newborns and Infants A crucial amount of growth and development happens between birth to age two. For proper growth, development, and brain function, this age group requires nutrient-dense food choices, primarily because they eat so little compared to adults, but also because of their rapid growth rate that is higher than any other time of development. Ideally, newborns through age six months should be fed exclusively human breast milk, if possible, to develop immunity. Vitamin D and iron supplementation may be needed. For the first two to three days after birth, human milk contains colostrum, a thick yellowish-white fluid rich in proteins and immunoglobulin A (IgA). There are many reasons infants may not be breastfed, including insufficient breast milk production, a personal choice not to breastfeed, or adoption of the newborn. If breastfeeding is not an option, an iron-fortified commercial infant formula should be used exclusively through at least six months of age. Infants fed 100% commercial infant formula will not need vitamin D supplementation. After about six months of age, infants should begin to be introduced to additional nutrient-dense complementary foods that are developmentally appropriate. Foods should be introduced one at a time to monitor for food sensitivities. Introducing food at this time is to provide a varied diet, additional nutrients, and an introduction to different flavours and textures of food. Research shows that introduction to certain allergy-risk foods, such as peanut butter prior to one year of age, helps decrease the risk of developing a peanut allergy later in life (Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy, 2024). It is important to strictly avoid honey and other unpasteurised food and drink before one year of age to prevent botulism and other bacteria due to immature gut immunity. Additionally, cow’s milk, fortified soy drinks, and fruit or vegetable juices should not be introduced before one year of age. |

|

Children and Adolescents Growth rate continues to be rapid from ages one through five, requiring adequate nutrition to meet these growth and metabolic demands. Kilojoule and nutritional intake requirements increase proportionately with age, but unfortunately, the quality of diet tends to decrease proportionately with age. This is in part due to younger children being dependent on adults for nutritional choices and intake while older children and adolescents begin to make their own food choices as they enter school. Healthy dietary habits formed in childhood through adolescence help prevent obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, and other chronic diseases later in life. It is important to provide children with a variety of different foods prepared in different ways to increase the likelihood of children accepting and growing accustomed to different foods. It is common for children to become picky in their food choices or decide to only eat one or a few different food items over a period of time. Allowing children to help select and prepare food can increase their acceptance of different food choices. |

|

|

Adults A major limiting factor to healthy nutrition in adults is the development of poor nutritional habits early in life. These unhealthy diet habits can be very difficult to change due to food preferences, as well as lack of knowledge about proper nutrition. Metabolic rate and kilojoule needs decrease with increasing age. Females tend to require less kilojoule intake than males, though kilojoule and nutritional needs increase with pregnancy and breastfeeding. Without appropriate dietary intake or activity, weight gain will occur that can lead to obesity and other chronic diseases. Education regarding a healthy diet, including appropriate kilojoules, saturated fat, sugar, and sodium intakes, helps improve health in adults. |

|

|

Pregnancy and Lactation A well-balanced, healthy diet is essential during pregnancy and lactation to prevent maternal, foetal, and newborn problems. Nutritional requirements, such as kilojoules, vitamins, and minerals, increase during pregnancy and lactation. Increased kilojoule needs should be met with nutrient-dense foods rather than kilojoule-dense foods that are higher in fats and sugars. Prenatal vitamins and mineral supplements are often prescribed during pregnancy and lactation, in addition to a nutrient-rich diet, to help ensure women meet requirements for folic acid, iron, iodine, choline, and vitamin D. Folic acid is necessary to prevent neural tube defects in the foetus during the first trimester of pregnancy. Iron requirements increase during pregnancy to support foetal development and prevent anaemia. Iodine requirements increase during pregnancy and lactation for foetal neurocognitive development. |

|

|

Older Adults Older adults are more likely to suffer from chronic illness and disease. Older adults have lower kilojoule needs than younger people, though they still need a diet full of nutrient-dense foods because their nutrient needs increase. Kilojoule needs decrease due to decreased activity, decreased metabolic rates, and decreased muscle mass. Chronic disease and medication can contribute to decreased nutrient absorption. Protein and vitamin B12 are commonly underconsumed in older adults. Protein is necessary to prevent loss of muscle mass. Vitamin B12 deficiency can be a problem for older adults because absorption of vitamin B12 decreases with age and with certain medications. Adequate hydration is also a concern for older adults because feelings of thirst decrease with age, leading to poor fluid intake. Additionally, older adults may be concerned with bladder dysfunction so they may consciously choose to limit fluid intake. Loneliness, ability to chew and swallow, and poverty can also decrease dietary intake in older adults.

|

Altered Nutrition

Malnutrition

Malnutrition is defined as a deficiency in nutrients such as energy, protein, vitamins, and minerals, leading to adverse impacts on body composition, function, or clinical outcomes (Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care [ACSQHC], 2018). It encompasses both undernutrition and overnutrition and can both cause and result from poor health (ACSQHC, 2018). Patients who are malnourished require more substantial care, rely more heavily on hospital resources, have higher healthcare costs, and face the possibility of longer hospital stays with increased risk of morbidity and mortality (Cass and Charlton, 2022). Consequently, Australian hospitals now incorporate nutrition screening into their admission protocols, focusing on identifying and managing undernourished patients and addressing malnutrition in those below a healthy weight (Elliot et al., 2023).

Malnutrition Screening

Malnutrition screening is a key component of nutritional care, particularly for older adults and hospitalised patients. Screening identifies individuals who are malnourished or at risk of malnutrition so that further assessment and intervention plans can be implemented (Dent et al., 2023). With malnutrition in acute hospitals estimated at approximately 40% (ACSQHC, 2018), it is recommended that hospitals have systems in place that identify, prevent and manage malnutrition.

Link to Learning

Read the ACSQHC factsheet, Hospital-Acquired Complication – 13. Malnutrition, about selected best practice and suggestions for improvement of hospital-acquired malnutrition to learn more about recommendations for malnutrition in hospitalised patients.

Screening Tools

|

Several screening tools exist, and their use will depend on the health facility. Nurses need to understand nutritional assessment and be able to perform a basic evaluation, identify those at risk, and refer them for further assessment by a dietitian. A valid tool should be used for screening; however, no one tool can be recommended over the other (Moola, 2022).

By incorporating these screening tools into the admission process, healthcare providers can ensure that patients receive the necessary nutritional care to support their overall health and recovery.

|

Dysphagia

Dysphagia, also known as difficulty swallowing, is common in a range of conditions such as stroke, dementia, Parkinson’s disease, and head and neck cancers (McIntosh, 2023). This condition puts the patient at risk of malnutrition, dehydration, aspiration pneumonia and airway obstruction (McIntosh, 2023; Heaton et al., 2020).

Detection and Management of Dysphagia

Nurses play a vital role in the detection and management of dysphagia.

Detection

Management

The main goal in the management of dysphagia includes reducing the risk of aspiration and ensuring adequate nutrition and hydration. Nurses’ responsibility is to provide oral and airway care, safe feeding practices and respiratory monitoring (Rose et al., 2025).

The nurse can implement the following interventions to reduce the risk of aspiration.

- Emergency suction equipment should be checked and nearby.

- Ensure appropriate oral hygiene and assist where required.

- Position the person at 30 to 45 degrees, especially if they are receiving tube feeds (Rose et al., 2025).

- Ensure the person is fully alert prior to commencing meals.

- Sit the person out of bed in a chair for meals when possible.

- Provide a quiet and distraction-free environment during meals.

- Ensure meals supplied meet prescribed diet requirements (IDDSI framework see below).

- Guide patient to take small mouthfuls, and to complete mouthful prior to the next.

- If choking or coughing occurs, remove food and reassess swallow.

- Check mouth for residual food after completion of meal.

- Keep person in upright position for approximately 20-30 minutes post eating to prevent regurgitation (McIntosh, 2023).

Modified Diet for Dysphagia

The International Dysphagia Diet Standardised initiative (IDDSI) framework was adopted in Australia in 2019 for the labelling and testing of modified texture of food and fluids. The framework is endorsed by Speech Pathology Australia and the Dieticians Association of Australia.

The IDDSI framework consists of eight levels (0–7) describing texture-modified foods and thickened liquids used for individuals with dysphagia. Click or tap on the “+” buttons below to read more about these levels.

Link to Learning

For a more detailed description of the levels please see the Complete IDDSI Framework Detailed Definitions 2.0.

Prescribed Special Diets

Patients may be prescribed a special diet to treat a disease process, to prepare for examination or surgery or to allow rest and recovery of organs. Diets may be modified in texture, energy, nutrients, seasoning or consistency. See Table 1 for variations in prescribed special diets.

| Diet | Description | Example | Indication |

|

NBM |

Nothing by mouth–no food or drink allowed |

Oral care only |

Before and after surgery or procedures. When peristalsis is absent, or during severe nausea or vomiting episodes.

|

|

Clear Fluids |

Fluids or solids that are liquid at room temperature, without residue, clear, or see-through

|

Water, apple juice, black tea or coffee, jelly, ice-blocks, and broth |

After surgery, when peristalsis is slow and diet is being advanced from NBM status |

|

Full Fluids |

Fluids with residue |

Creamed soups, milk, custard, ice-cream, orange juice, and creamed cereals

|

Next step after clear fluids, as diet is being advanced |

|

Lite diet |

Normal consistency foods with low residue containing low seasoning fats and salt

|

Reduced fat, reduced salt plain foods |

May be prescribed following full fluids before advancing to Full diet. |

| Full diet

|

There is no restriction on diet |

No restriction |

No indication requiring restriction |

| Minced diet

|

Chopped, ground, pureed foods that break apart easily without a knife |

Soft cheeses, cottage cheese, ground meat, broiled or baked fish, cooked vegetables, and fruit

|

Poor or absent dentition; dysphagia |

|

Pureed |

Spoon thick with consistency of baby food |

Applesauce, mashed potatoes, pureed meats, vegetables, and fruit

|

Dysphagia |

|

Restrictive |

Modified dependent on disease process |

Diabetic: controlled amount of carbohydrates |

Diabetes mellitus |

|

|

|

Cardiac: low fat and no added salt |

Heart disease |

|

|

|

Renal: low-sodium and low-potassium containing foods |

Renal failure or dialysis |

Assessing Nutrition

While a full nutritional assessment is often conducted by a dietitian, nurses are required to screen nutritional status and refer for further assessment if needed. Kesari and Noel (2023) indicate that a systematic approach to nutritional assessment should be undertaken, which includes clinical examination, diagnostic tests, and dietary assessments. One such approach is the ABCDE approach to nutritional assessment: anthropometric, biochemical, clinical, dietary, and environmental factors.

General Information – the Health Interview

Begin the health interview by collecting information on the patient’s age, sex, medication history, past medical, surgical history, current activity levels, and overall general health status.

ABCDE Approach to Nutritional Assessment

Height, Weight and BMI Measurements

Height and weight should be accurately measured and documented. Height should be measured with the patient standing whenever possible. Weight is most accurately assessed in the morning prior to any dietary input. It should be taken on the same scale with similar weight clothing and at the same time on each occasion. Weight of the patient is normally recorded on admission and weekly thereafter if considered for weight management. If weight is required for fluid management, then it is taken daily.

Height and weight in infants and children are plotted on a growth chart to give a percentile ranking. The infant or child should show a trend of consistent height and weight increase.

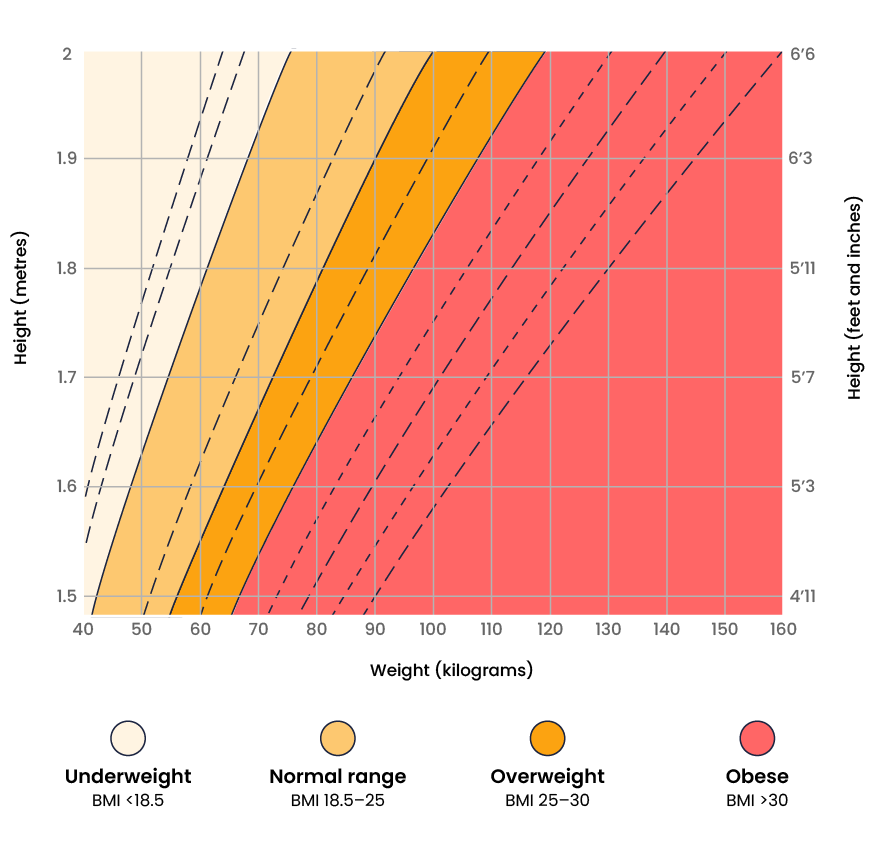

Height and weight in adults are used to calculate a patient’s Body Mass Index (BMI). BMI is a body composition measure comparing weight relative to height.

- BMI = weight (kg)/height (m2)

To calculate BMI using a BMI table, the person’s height is plotted on the horizontal axis and their weight is plotted on the perpendicular axis. The BMI is measured where the lines intersect. See Figure 6 for an image of a BMI table. BMI is interpreted using the following ranges:

- Less than 18.5: Underweight

- 18.5-24.9: Desirable range

- 25-29.9: Overweight

- Equal or greater than 30: Obese

Please note, although commonly used in healthcare settings, BMI is not indicative of an individual’s overall health status and can be inaccurate for certain populations.

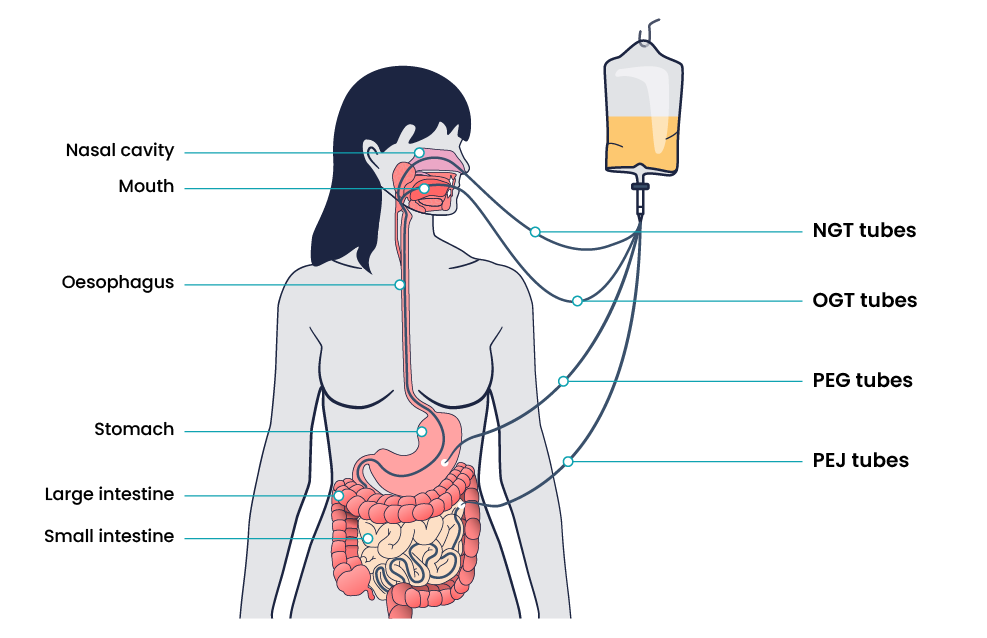

Enteral Nutrition

Enteral nutrition is administered directly to a patient’s gastrointestinal tract while bypassing chewing and swallowing. Enteral feedings are prescribed for patients when chewing and/or swallowing are impaired or when there is poor nutritional intake and/or malnutrition. Examples of enteral tube access are:

See Figure 7 for an illustration of common enteral tube placement.

Management and Monitoring of Enteral Feeding

There are several safety considerations for nurses to implement when enteral nutrition is being administered to prevent aspiration and dehydration. Tube placement must be verified after insertion, as well as before every medication or feeding is administered, to prevent inadvertent administration into the lungs if the tube has migrated out of position. Follow your organisational policy regarding checking placement. Generally, this is checked by measuring the visible tube length and comparing it to the length documented during X-ray verification. Older methods of checking tube placement included observing aspirated GI contents or the administration of air with a syringe while auscultating (commonly referred to as the “whoosh test”). However, research has determined these methods are unreliable and should no longer be used to verify placement.

In addition to verifying tube placement before administering feedings or medications, nurses perform additional interventions to prevent aspiration. The following guidelines help to reduce the risk of aspiration:

- Maintain the head of the bed at 30°–45° unless contraindicated

- Use sedatives as sparingly as possible

- Assess feeding tube placement at four‐hour intervals

- Observe for change in the amount of external length of the tube

- Assess for gastrointestinal intolerance at four‐hour intervals.

Gastric residual volume (GRV) monitoring is used in patients receiving enteral nutrition (EN) to assess feeding tolerance and absorption of feeds to reduce the risk of vomiting and possible aspiration. GRV is checked by aspirating all gastric contents of the stomach. The aspirated volume is measured and recorded. The number of millilitres of fluid aspirated from the stomach is noted and depending on the hospital policy, the GRV will either be returned (if acceptable volume) or discarded (if high volume) and the feed either ceased to rest the gut (if high volume), continued at current rate (if acceptable GRV), or increased if goal rate of feeds is not yet achieved. Determination of intolerance should be done in conjunction with other signs such as abdominal bloating, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, cramping, and constipation.

The nasogastric feed procedure is discussed below.

Total Parenteral Nutrition (TPN)

Parenteral nutrition is nutrition delivered through a central intravenous line, generally the subclavian or internal jugular vein, to patients who require nutritional supplementation but are not candidates for enteral nutrition. Parenteral nutrition is an intravenous solution containing glucose, amino acids, minerals, electrolytes, and vitamins. A lipid solution is typically given in a separate infusion in a hospital setting. This combination of solutions is called total parenteral nutrition because it supplies complete nutritional support. Parenteral nutrition is administered via an IV pump. Because parenteral nutrition consists of concentrated glucose, amino acids, and minerals, it is very irritating to the blood vessels. For this reason, a large central vein must be used for administration. The patient’s pathology results must also be closely monitored for signs of nutrient excesses.

Parental nutrition is generally made up of three compartments: one with glucose, one with amino acids, and one with lipids. The three compartments are kept separate to enable storage at room temperature but are mixed together before use. Parenteral nutrition is typically used when the patient’s intestines or stomach is not working properly and must be bypassed, such as during paralytic ileus where peristalsis has completely stopped, or after postoperative bowel surgeries, such as bowel resection. It may also be prescribed for severe malnutrition, severe burns, metastatic cancer, liver failure, or hyperemesis with pregnancy.

Nursing Interventions

|

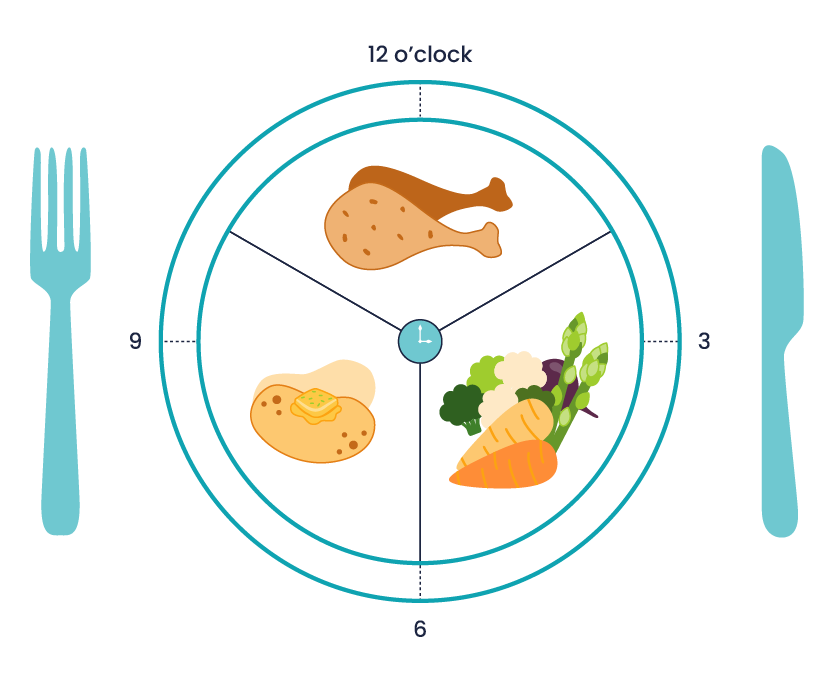

Promoting Appetite and Providing Meal AssistanceProvide foods that patient enjoys. If unavailable in the facility, suggest to the family to bring foods from home. (Be conscious of any diet restrictions.) Provide hygiene. Assist to wash hands. Provide oral hygiene to enhance the ability to taste. Ensure comfort during meals. Manage symptoms of pain or nausea prior to mealtimes. Offer to use the restroom if needed. Avoid procedures immediately prior to meals. Schedule wound dressing or invasive procedures that may impact appetite after meals when able. Remove any unpleasant odours or sights. Remove any urinals, bedpans, commodes from the area and ensure the area is free from clinical waste. Position the patient. Assist them to sit in a chair or sit in high Fowler’s position in bed. Set the meal tray on an overbed table and open containers as needed. Encourage independence. Utilise modified utensils to assist and maintain independence if required. Options include grip mats, plates with grip edges, cups with lids and easy grip, wide grip cutlery (See Figure 8 below). Assisting the patient. Ask the patient what food they would like and when. Do not rush the patient, allow them to eat at their own pace with time between bites for thorough chewing and swallowing. Vision impairment. Explain the location of the food using the clock method. For example, “Your vegetables are at 3 o’clock, your potatoes are at 9 o’clock, and your meat is at 12 o’clock.” (See Figure 9 below) Safety. Monitor for signs of difficulty swallowing, such as coughing or gagging. If it occurs, stop the meal and notify the medical staff of suspected swallowing difficulties.

|

Blood Glucose Monitoring

Key Takeaways

In this chapter, we covered:

- The importance of nutrition and how it plays a vital role in overall health and well-being by assisting in the prevention and treatment of disease

- The structure and function of the gastrointestinal/digestive system

- Essential nutrients and how they are used by the body for growth, energy and bodily processes. These include Macronutrients (carbohydrates, protein, fats) and Micronutrients (vitamins and minerals).

- Factors affecting nutrition such as growth and development, gender, health status, cultural and religious beliefs, socioeconomic status, medication, surgery, alcohol consumption and psychological factors

- Lifespan considerations of newborns and infants, children and adolescents, adults, pregnancy and lactation, and older adults for nutritional requirements

- Alteration in nutrition, such as malnutrition, and screening tools for this, as well as dysphagia and its detection and management

- Commonly prescribed diets such as NBM, clear fluids, full fluids, mechanical soft, pureed, restrictive and thickened fluids

- How to assess nutritional status with the ABCDE approach along with height, weight and BMI measurements

- Different ways to deliver nutrition, including enteral nutrition, nasogastric tubes (NGT), orogastric tubes, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tubes, as well as total parenteral nutrition

- Nursing interventions to promote good nutrition and assist patients with feeding to promote independence.

References

Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy. (2024). How to introduce solid foods to babies for allergy prevention. https://www.allergy.org.au/patients/allergy-prevention/ascia-how-to-introduce-solid-foods-to-babies

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. (2018). Hospital-acquired complication 13 malnutrition fact sheet. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/publications-and-resources/resource-library/hospital-acquired-complication-13-malnutrition-fact-sheet

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. (2022). National standard for user-applied labelling of injectable medicines, fluids and lines. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/publications-and-resources/resource-library/user-applied-labelling-standard-issues-register

Berman, A., Snyder, S., Levett-Jones, T., Burton, T., & Harvey, N. (2021). Skills in clinical nursing (2nd ed.). Pearson Australia.

Brazier, Y. (2020, December 10). Protein deficiency: How much protein does a person need? Medical News Today. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/196279

Cass, A. R., & Charlton, K. E. (2022). Prevalence of hospital‐acquired malnutrition and modifiable determinants of nutritional deterioration during inpatient admissions: A systematic review of the evidence. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics, 35(6), 1043–1058. https://doi.org/10.1111/jhn.13009

Christidis, R., Lock, M., Walker, T., Egan, M., & Browne, J. (2021). Concerns and priorities of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples regarding food and nutrition: A systematic review of qualitative evidence. International Journal for Equity in Health, 20(1), 220–19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-021-01551-x

Dent, E., Wright, O. R. L., Woo, J., & Hoogendijk, E. O. (2023). Malnutrition in older adults. The Lancet (British Edition), 401(10380), 951–966. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)02612-5

Janowski, M. (2023). Screening. In J. Doley, M. J. Marian (Eds.), Adult malnutrition: Diagnosis and treatment (Vol. 1). CRC Press. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781003177586

Elliott, A., Gibson, S., Bauer, J., Cardamis, A., & Davidson, Z. (2023). Exploring overnutrition, overweight, and obesity in the hospital setting—A point prevalence study. Nutrients, 15(10), Article 2315. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15102315

Fialkowski Revilla, M. K., Titchenal, A., Calabrese, A., Gibby, C., & Meinke, B. (2017). Human nutrition [deprecated]. University of Hawai’i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program. https://pressbooks-dev.oer.hawaii.edu/humannutrition/

Heaton, S., Farrell, A., & Bassett, L. (2020). Implementation of hospital wide dysphagia screening in a large acute tertiary teaching hospital. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 22(1), 95–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549507.2019.1597922

Johnson, L. E. (2024, August). Overview of vitamins. In Merck Manual Professional Version. Retrieved March 18, 2025, from https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/nutritional-disorders/vitamin-deficiency,-dependency,-and-toxicity/overview-of-vitamins?redirectid=43#v2089966

Keeton, W. T. & Hightower, N. C. (2025). The gastrointestinal tract as an organ of immunity. In Encyclopædia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/science/human-digestive-system/The-gastrointestinal-tract-as-an-organ-of-immunity

Kesari, A., Noel, J. Y. (2023). Nutritional assessment. In W. B. Ackley, T. S. Adolphe, T. C. Aeby, N. R. Aeddula, S. Agadi, P. Agasthi, S. Ahmad, A. Ahmed, F. W. Ahmed, I. Ahmed, R. A. Ahmed, S. W. Ahmed, A. M. Akanmode, R. Akella, S. M. Akram, Y. Al Khalili, E. Al Zaabi, M. H. Alahmadi, G. Alexander, … H. Zulfiqar (Eds). StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved March 17, 2025 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK580496/

Kris-Etherton, P. M., Petersen, K. S., Hibbeln, J. R., Hurley, D., Kolick, V., Peoples, S., Rodriguez, N., & Woodward-Lopez, G. (2021). Nutrition and behavioral health disorders: Depression and anxiety. Nutrition Reviews, 79(3), 247–260. https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuaa025

LibreTexts. (2024). Anatomy and physiology (boundless). https://med.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Anatomy_and_Physiology/Anatomy_and_Physiology_(Boundless)

Lizarondo, L & Queiroz, A. B. (2023). Dysphagia in acute care: Nurse-initiated screening [JBI Evidence Summaries]. http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=jbi&NEWS=N&AN=JBI121994

Mahboub, N., Rizk, R., Karavetian, M., & de Vries, N. (2021). Nutritional status and eating habits of people who use drugs and/or are undergoing treatment for recovery: A narrative review. Nutrition Reviews, 79(6), 627–635. https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuaa095

McIntosh, E. (2023). Dysphagia. Home Healthcare Now, 41(1), 36–41. https://doi.org/10.1097/NHH.0000000000001134

Moola, S. (2022). Nutritional screening tools: Hospitalized adults (non-specific conditions) [JBI Evidence Summaries]. http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=jbi&NEWS=N&AN=JBI13467

Morris, N. F., Stewart, S., Riley, M. D., & Maguire, G. P. (2016). The Indigenous Australian Malnutrition Project: The burden and impact of malnutrition in Aboriginal Australian and Torres Strait Islander hospital inpatients, and validation of a malnutrition screening tool for use in hospitals—study rationale and protocol. SpringerPlus, 5(1), Article 1296. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40064-016-2943-5

National Health and Medical Research Council. (2013). Australian dietary guidelines. Australian Government. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/australian-dietary-guidelines-2013.pdf

Palmer, M., Hill, J., Hosking, B., Naumann, F., Stoney, R., Ross, L., Woodward, T. & Josephson, C. (2021). Quality of nutritional care provided to patients who develop hospital acquired malnutrition: A study across five Australian public hospitals. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics, 34(4), 695-704. https://doi.org/10.1111/jhn.12876

Rose, L., Spronk, P., & Skoretz, S. (2025). The key role of intensive care nurses in critical illness dysphagia assessment, prevention, and management. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing, 87, Article 103935. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2024.103935

Scott, S., Muir, C., Stead, M., Fitzgerald, N., Kaner, E., Bradley, J., Wrieden, W., Power, C., & Adamson, A. (2020). Exploring the links between unhealthy eating behaviour and heavy alcohol use in the social, emotional and cultural lives of young adults (aged 18–25): A qualitative research study. Appetite, 144, Article 104449. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2019.104449

Singh M. (2014). Mood, food, and obesity. Frontiers in Psychology, 5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00925

Tamburri, L. M., Hollender, K. D., & Orzano, D. (2020). Protecting patient safety and preventing modifiable complications after acute ischemic stroke. Critical Care Nurse, 40(1), 56–65. https://doi.org/10.4037/ccn2020859

MedlinePlus. (2024). Minerals. US National Library of Medicine. https://medlineplus.gov/minerals.html

Williams, S. L., & Quinney, L. (2020). Nutrition. In A. Berman, G. Frandsen, S. Snyder, T. Levett-Jones, A. Burston, T. Dwyer, M. Hales, N. Harvey, T. Langtree, L. Moxham, K. Reid-Searl, F. Rolf, & D. Stanley (Eds.), Kozier and Erb’s fundamentals of nursing: Concepts, process and practice (5th Australian ed., pp. 2695-2833). Pearson Australia.

Youdim, A. (2019). Overview of nutrition. Merck Manual Professional Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/nutritional-disorders/nutrition-general-considerations/overview-of-nutrition

Chapter Attribution

This chapter has been adapted in parts from:

Nursing Fundamentals 2e (n.d.) by Open Resources for Nursing, Chippewa Valley Technical College is used under a CC BY licence.

Media Attributions

- Private:

- Gastrointestinal System © Eileen Siddins is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Glycemic Index © Eileen Siddins is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Protein-Rich Foods © Smastronardo is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Subjective Interviewing © Ben Green is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Measuring Height and Weight © Ben Green is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- BMI Chart © People: Staff activities in IITA adapted by Eileen Siddins is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Enteral Tube Access © Eileen Siddins is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Eating Utensils © Amy McCrystal is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Food Location on Plate © Eileen Siddins is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license