Assessment of the Integumentary System

Kate Hurley and Sandra Dash

Learning Outcomes

In this chapter, you will learn how to:

- Describe the integumentary system and its function

- Define the layers of the skin and examine their unique function

- Describe the changes that occur in the integumentary system during the ageing process

- Describe the process of skin assessment and identify factors that impact skin integrity

- Recognise several common diseases, disorders, and injuries that affect the integumentary system.

The integumentary system is the largest and most visible body organ and is composed of the skin, hair, nails, sebaceous glands, eccrine and apocrine sweat glands. In the adult human body, the skin makes up about 15% of body weight and covers an area of 1.5 to 2 square metres (Carville, 2024). In fact, the skin and accessory structures are the largest organ systems in the human body. As such, the skin protects your inner organs, and it needs daily care and protection to maintain its health.

Conducting a routine head-to-toe assessment requires the nurse to assess the skin, hair, and nails. During inpatient care, a comprehensive skin assessment on admission establishes a baseline for the condition of a patient’s skin and is essential for developing a care plan for the prevention and treatment of skin injuries.

This chapter will introduce the structure and functions of the integumentary system, as well as some of the diseases, disorders, and injuries that can affect this system.

The Skin Layers

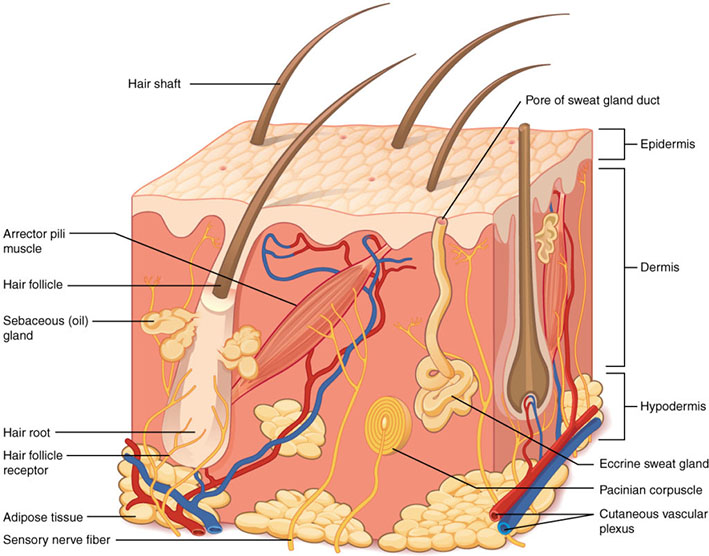

The skin and its accessory structures make up the integumentary system, which provides the body with overall protection. The skin is made of multiple layers of cells and tissues, which are held to underlying structures by connective tissue (Figure 1). The deeper layer of skin is well vascularised (has numerous blood vessels). It also has numerous sensory, and autonomic and sympathetic nerve fibres ensuring communication to and from the brain.

Epidermis

The epidermis is composed of keratinised, stratified squamous epithelium. It is made of four or five layers of epithelial cells, depending on its location in the body. It does not have any blood vessels within it (i.e., it is avascular). Skin that has four layers of cells is referred to as “thin skin.” From deep to superficial, these layers are the stratum basale, stratum spinosum, stratum granulosum, and stratum corneum. Most of the skin can be classified as thin skin. “Thick skin” is found only on the palms of the hands and the soles of the feet. It has a fifth layer, called the stratum lucidum, located between the stratum corneum and the stratum granulosum.

Dermis

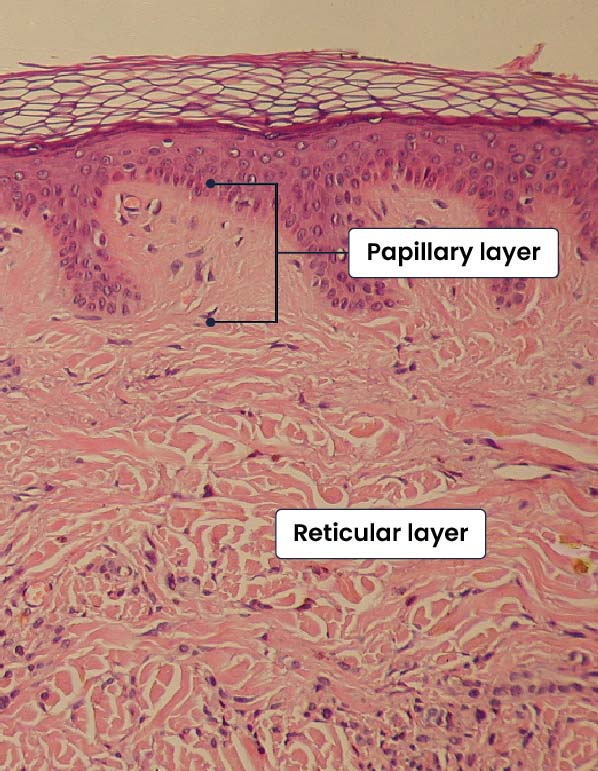

The dermis might be considered the “core” of the integumentary system (derma- = “skin”), as distinct from the epidermis (epi- = “upon” or “over”) and hypodermis (hypo- = “below”). It contains blood and lymph vessels, nerves, and other structures, such as hair follicles and sweat glands. The dermis is made of two layers of connective tissue that compose an interconnected mesh of elastin and collagenous fibres, produced by fibroblasts (see Figure 2).

Hypodermis

The hypodermis (also called the subcutaneous layer or superficial fascia) is a layer directly below the dermis and serves to connect the skin to the underlying fascia (fibrous tissue) of the bones and muscles. It is not strictly a part of the skin, although the border between the hypodermis and dermis can be difficult to distinguish. The hypodermis consists of well-vascularised, loose, areolar connective tissue and adipose tissue, which functions as a mode of fat storage and provides insulation and cushioning for the integument.

Pigmentation

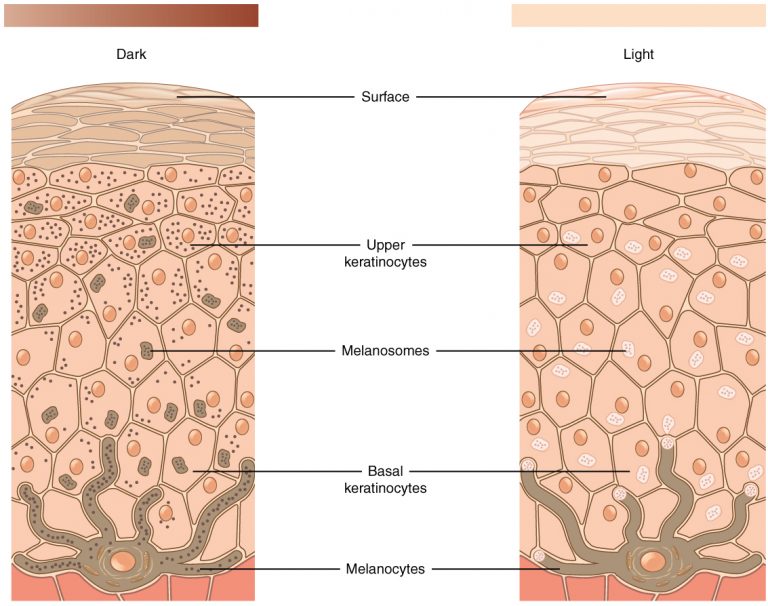

The colour of skin is influenced by a number of pigments, including melanin, carotene, and haemoglobin. Melanin is produced by cells called melanocytes, which are found scattered throughout the stratum basale of the epidermis. The melanin is transferred into the keratinocytes via a cellular vesicle called a melanosome (see Figure 3).

Melanin occurs in two primary forms. Eumelanin exists as black and brown, whereas pheomelanin provides a red colour. Dark-skinned individuals produce more melanin than those with pale skin. Exposure to the UV rays of the sun or a tanning salon causes melanin to be manufactured and built up in keratinocytes, as sun exposure stimulates keratinocytes to secrete chemicals that stimulate melanocytes. The accumulation of melanin in keratinocytes results in the darkening of the skin, or a tan. This increased melanin accumulation protects the DNA of epidermal cells from UV ray damage and the breakdown of folic acid, a nutrient necessary for our health and well-being. In contrast, too much melanin can interfere with the production of vitamin D, an important nutrient involved in calcium absorption. Thus, the amount of melanin present in our skin is dependent on a balance between available sunlight and folic acid destruction, and protection from UV radiation and vitamin D production.

Too much sun exposure can eventually lead to wrinkling due to the destruction of the cellular structure of the skin, and in severe cases, can cause sufficient DNA damage to result in skin cancer. When there is an irregular accumulation of melanocytes in the skin, freckles appear. Moles are larger masses of melanocytes, and although most are benign, they should be monitored for changes that might indicate the presence of cancer.

Accessory Structures

Accessory structures of the skin include hair, nails, sweat glands, and sebaceous glands. These structures embryologically originate from the epidermis and can extend down through the dermis into the hypodermis.

Hair

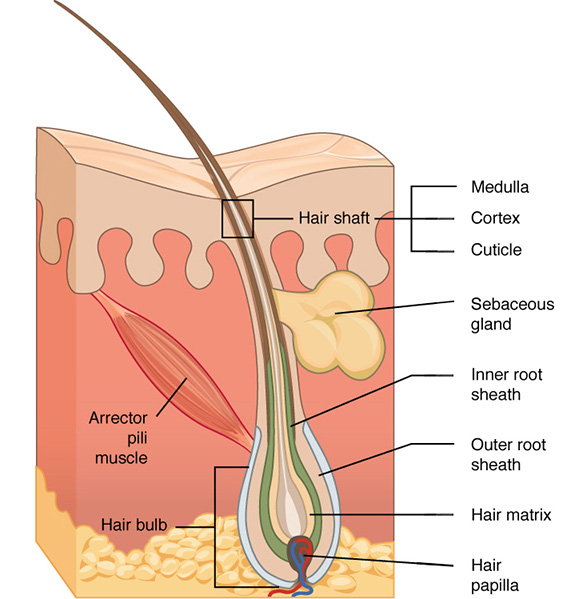

Hair is a keratinous filament growing out of the epidermis. It is primarily made of dead, keratinised cells. Strands of hair originate in an epidermal penetration of the dermis called the hair follicle. The hair shaft is the part of the hair not anchored to the follicle, and much of this is exposed at the skin’s surface. The rest of the hair, which is anchored in the follicle, lies below the surface of the skin and is referred to as the hair root. The hair root ends deep in the dermis at the hair bulb and includes a layer of mitotically active basal cells called the hair matrix. The hair bulb surrounds the hair papilla, which is made of connective tissue and contains blood capillaries and nerve endings from the dermis (see Figure 4).

Hair serves a variety of functions, including protection, sensory input, thermoregulation, and communication. For example, hair on the head protects the skull from the sun. The hair in the nose and ears, and around the eyes (eyelashes) defends the body by trapping and excluding dust particles that may contain allergens and microbes. The hair of the eyebrows prevents sweat and other particles from irritating the eyes. Hair also has a sensory function due to sensory innervation by a hair root plexus surrounding the base of each hair follicle. Hair is extremely sensitive to air movement or other disturbances in the environment, much more so than the skin surface. This feature is also useful for the detection of the presence of insects or other potentially damaging substances on the skin surface.

Nails

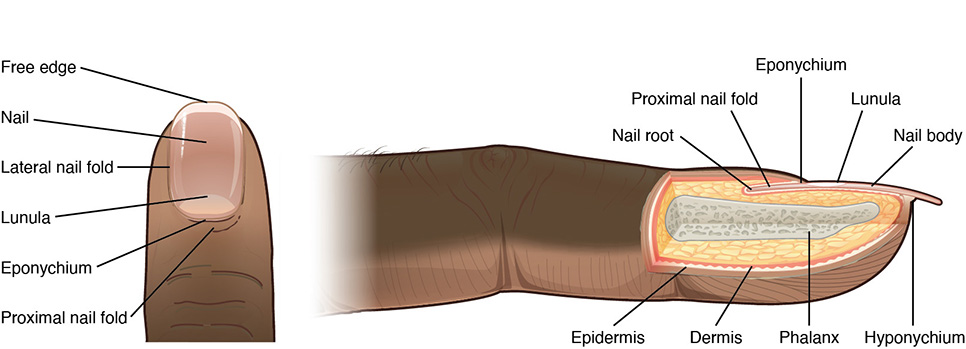

The nail bed is a specialised structure of the epidermis that is found at the tips of our fingers and toes. The nail body is formed on the nail bed and protects the tips of our fingers and toes as they are the farthest extremities and the parts of the body that experience the maximum mechanical stress (Figure 5). In addition, the nail body forms a back-support for picking up small objects with the fingers. The nail body is composed of densely packed dead keratinocytes. The epidermis in this part of the body has evolved a specialised structure upon which nails can form.

Sweat Glands

Sweat glands develop from epidermal projections into the dermis and are classified as merocrine glands; that is, the secretions are excreted by exocytosis through a duct without affecting the cells of the gland. There are two types of sweat glands, each secreting slightly different products.

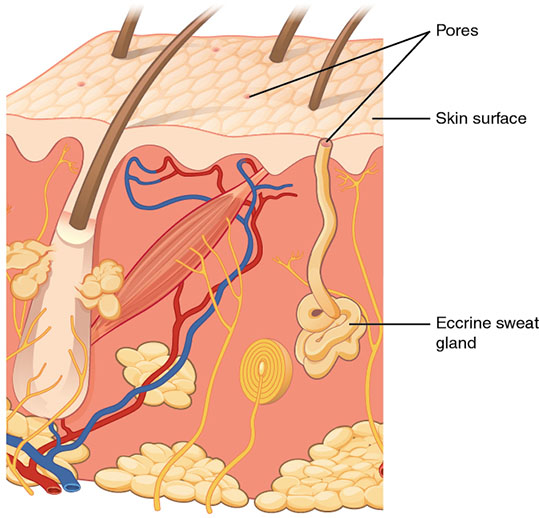

An eccrine sweat gland is a type of gland that produces a hypotonic sweat for thermoregulation (Figure 6). These glands are found all over the skin’s surface but are especially abundant on the palms of the hand, the soles of the feet, and the forehead. An apocrine sweat gland is usually associated with hair follicles in densely hairy areas, such as armpits and genital regions. Apocrine sweat glands are larger than eccrine sweat glands and lie deeper in the dermis, sometimes even reaching the hypodermis, with the duct normally emptying into the hair follicle.

Sebaceous Glands

A sebaceous gland is a type of oil gland that is found all over the body and helps to lubricate and waterproof the skin and hair. Most sebaceous glands are associated with hair follicles. They generate and excrete sebum, a mixture of lipids, onto the skin surface, thereby naturally lubricating the dry and dead layer of keratinised cells of the stratum corneum, keeping it pliable.

Diseases, Disorders and Injuries

The integumentary system is susceptible to a variety of diseases, disorders, and injuries. These range from annoying but relatively benign bacterial or fungal infections that are categorised as disorders, to skin cancer and severe burns, which can be fatal. In this section, you will learn about several of the most common skin conditions.

Diseases

One of the most talked about diseases is skin cancer. Cancer is a broad term that describes diseases caused by abnormal cells in the body dividing uncontrollably. Most cancers are identified by the organ or tissue in which the cancer originates. One common form of cancer is skin cancer. According to The Cancer Council, Australia has one of the highest instances of skin cancer worldwide and diagnosis of skin cancer accounts for around 80% of newly diagnosed cancers each year (Cancer Council, 2024). The degradation of the ozone layer in the atmosphere and the resulting increase in exposure to UV radiation has contributed to its rise. Overexposure to UV radiation damages DNA, which can lead to the formation of cancerous lesions. Although melanin offers some protection against DNA damage from the sun, often it is not enough. The fact that cancers can also occur on areas of the body that are normally not exposed to UV radiation suggests that there are additional factors that can lead to cancerous lesions.

In general, cancers result from an accumulation of DNA mutations. These mutations can result in cell populations that do not die when they should and uncontrolled cell proliferation that leads to tumours. Although many tumours are benign (harmless), some produce cells that can mobilise and establish tumours in other organs of the body; this process is referred to as metastasis. Cancers are characterised by their ability to metastasise.

Cancer Affecting the Skin

|

Basal cell carcinoma is a form of cancer that affects the mitotically active stem cells in the stratum basale of the epidermis. It is the most common of all cancers that occur in Australia and is frequently found on the head, neck, arms, and back, which are areas that are most susceptible to long-term sun exposure. Between 95% and 99% of skin cancers in Australia are caused by exposure to the sun (Cancer Council, 2024). UV rays and exposure to other agents, such as radiation and arsenic, can also lead to this type of cancer. Wounds on the skin due to open sores, tattoos, burns, etc. may be predisposing factors as well. Basal cell carcinomas start in the stratum basale and usually spread along this boundary. Basal cell carcinoma generally has no symptoms and tends to grow slowly without spreading to other parts of the body. It can often be distinguished as a pearly lump or a dry, scaly area that is shiny or pale in colour (Cancer Council, 2024). A biopsy is used to diagnose a basal cell carcinoma and like most cancers, basal cell carcinomas respond best to treatment when caught early. Treatment options include surgery, freezing (cryosurgery), and non-surgical management such as radiotherapy (Cancer Council, 2024).

|

|

Squamous cell carcinoma is a cancer that affects the keratinocytes of the stratum spinosum and is usually found on skin that has had sun exposure, such as the scalp, ears, and hands. Squamous cell carcinoma accounts for about 30% of non-melanoma skin cancers diagnosed in Australia annually (Cancer Council, 2024). These types of cancer are generally more aggressive than basal cell carcinoma and grow over a period of weeks to months (Cancer Council, 2024). If not removed, these carcinomas can metastasise. Surgery and radiation are used to cure squamous cell carcinoma.

|

|

A melanoma is a cancer characterised by the uncontrolled growth of melanocytes, the pigment-producing cells in the epidermis. Melanoma is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer in Australia with the average age of diagnosis at 65 years of age (Cancer Council, 2024). The risk of melanoma increases with exposure to UV radiation, having a high amount of moles on the body, a high number of unusual moles on the body, a decreased immune system, or a family history of melanoma (Cancer Council, 2024). Often melanoma has no symptoms, however, the first sign is generally a change in the appearance of an existing mole or the appearance of a new mole or freckle. The changes observed in an existing mole can be a change in colour, size, shape or elevation. The site may also become irritated and itch or bleed (Cancer Council, 2024). Melanomas usually appear as asymmetrical brown and black patches with uneven borders and a raised surface. Treatment typically involves surgical excision and immunotherapy. The factors to observe when diagnosing a potential melanoma include:

(Cancer Council, 2024). |

Disorders of the Skin

There are many common skin disorders that affect individuals. Three common conditions are eczema, acne and scabies. Eczema is an inflammatory condition that occurs in individuals of all ages. Acne involves the clogging of pores, which can lead to infection and inflammation and is often seen in adolescents. Scabies is a parasitic skin infestation, that is highly contagious. Other disorders, not discussed here, include seborrheic dermatitis, psoriasis, cold sores, impetigo, hives, and warts.

Eczema

Eczema is an allergic reaction that manifests as dry, itchy patches of skin that resemble rashes (Australian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy [ASCIA], 2024; see Figure 7). It may be accompanied by swelling of the skin, flaking, and in severe cases, bleeding. Eczema is more likely to develop in people who have allergies or a family history of allergy and studies have shown that infants with eczema, with a family history of allergies, will develop a food allergy as they develop, with a further 40% of these infants developing asthma and/or allergic rhinitis (hayfever; ASCIA, 2024). “Flares” or a worsening of eczema symptoms usually occur due to skin becoming increasingly dry, exposing the skin to allergens or irritants that can exacerbate itchiness. Symptoms are usually managed with good skin hygiene including avoiding soaps or body wash that dry the skin, avoiding excessive swimming in chlorinated pools, using non-fragranced moisturises and bathing in lukewarm water (ASCIA, 2024).

Acne

Acne is a skin disturbance that typically occurs on areas of the skin that are rich in sebaceous glands (face and back; see Figure 8). It is most common along with the onset of puberty due to associated hormonal changes but can also occur in infants and continue into adulthood. Hormones, such as androgens, stimulate the release of sebum. An overproduction and accumulation of sebum along with keratin can block hair follicles. This plug is initially white. The sebum, when oxidised by exposure to air, turns black. Acne results from infection by acne-causing bacteria (Propionibacterium and Staphylococcus), which can lead to redness and potential scarring due to the natural wound healing process.

Scabies

Scabies is a parasitic skin infection that is highly contagious. It is primarily transferred between humans by touch (skin-to-skin contact) and caused by small mites (Sarcoptes scabiei), that are barely visible to the naked eye. The incubation period can vary, and those who have had scabies before have a shorter incubation period (1–4 days) compared with those who have not previously been infected (2–6 weeks; Department of Health, 2024). The infection presents on the skin as elevated, whitish brown tunnels that generally contain mites and eggs, usually affecting spaces between the fingers, wrists, axillae, and abdomen. Itching varies but can be severe and scratching itchy areas can lead to secondary bacterial infections (Department of Health, 2024). Over time, the areas usually become inflamed, making the burrows less visible. Infestations that turn severe may cause areas of crusted, thickened skin that does not itch.

Injuries

The skin is vulnerable to injury as it protects the body from external sources, including sharp objects, heat, excessive pressure or friction. Skin injuries set off a healing process that occurs in several overlapping stages. The first step to repairing damaged skin is the formation of a blood clot that helps stop the flow of blood and scabs over time. Many different types of cells are involved in wound repair, especially if the surface area that needs repair is extensive. Before the basal stem cells of the stratum basale can recreate the epidermis, fibroblasts mobilise and divide rapidly to repair the damaged tissue by collagen deposition, forming granulation tissue. Blood capillaries follow the fibroblasts and help increase blood circulation and oxygen supply to the area. Immune cells, such as macrophages, roam the area and engulf any foreign matter to reduce the chance of infection.

Burns

A burn results when the skin is damaged by intense heat, radiation, electricity, or chemicals (World Health Organisation, 2024). The damage results in the death of skin cells, which can lead to a large loss of fluid. Dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, and renal and circulatory failure follow, which can be fatal. Burn patients are treated with intravenous fluids to offset dehydration, as well as intravenous nutrients that enable the body to repair tissues and replace lost proteins. Another serious threat to the lives of burn patients is infection. Burned skin is extremely susceptible to bacteria and other pathogens, due to the loss of protection by intact layers of skin.

Types of Burns

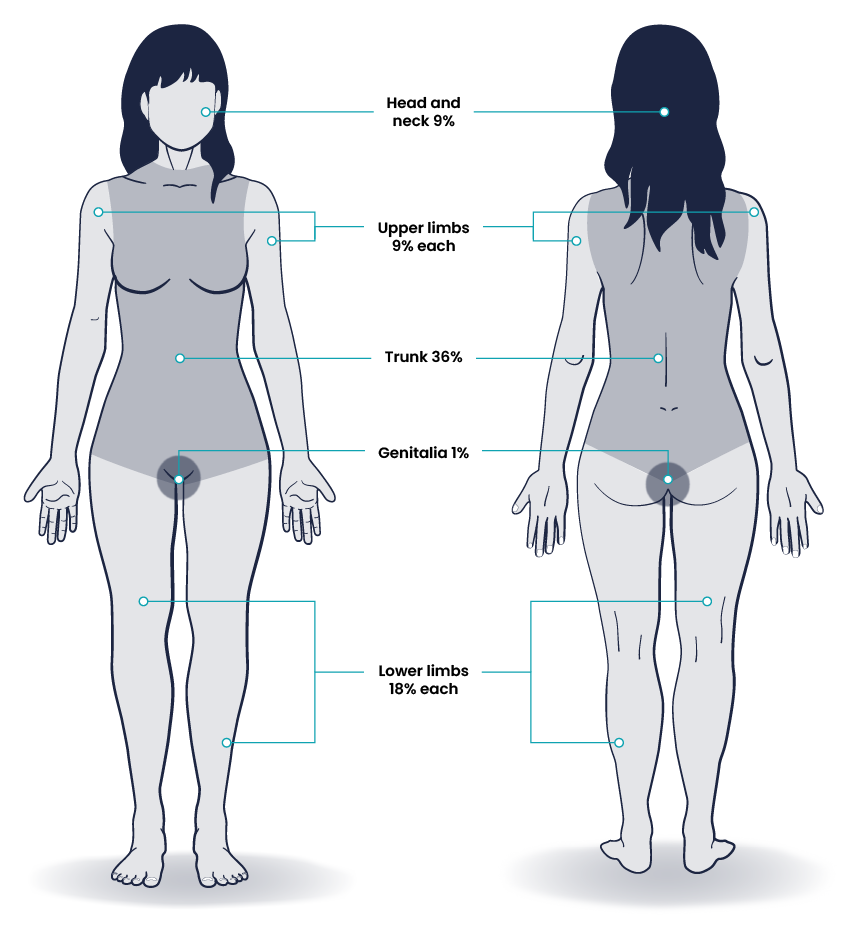

Burns are sometimes measured in terms of the size of the total surface area affected. This is referred to as the “rule of nines,” which associates specific anatomical areas with a percentage that is a factor of nine (see Figure 9). Burns are also classified by the degree of their severity.

Scars and Keloids

Most cuts or wounds, apart from ones that only scratch the surface (the epidermis), lead to scar formation. A scar is collagen-rich skin formed after the process of wound healing that differs from normal skin. Scarring occurs in cases in which there is repair of skin damage, but the skin fails to regenerate the original skin structure. Fibroblasts generate scar tissue in the form of collagen, and the bulk of repair is due to the basket-weave pattern generated by collagen fibres and does not result in regeneration of the typical cellular structure of skin. Instead, the tissue is fibrous in nature and does not allow for the regeneration of accessory structures, such as hair follicles, sweat glands, or sebaceous glands. Sometimes, there is an overproduction of scar tissue, because the process of collagen formation does not stop when the wound is healed; this results in the formation of a raised or hypertrophic scar called a keloid (National Health Service [NHS], 2023). In contrast, scars that result from acne and chickenpox have a sunken appearance and are called atrophic scars.

Scarring of skin after wound healing is a natural process and does not need to be treated further. The application of mineral oil and lotions may reduce the formation of scar tissue. However, modern cosmetic procedures, such as dermabrasion, laser treatments, and filler injections have been invented as remedies for severe scarring. All of these procedures try to reorganise the structure of the epidermis and underlying collagen tissue to make it look more natural.

Stretch Marks

The skin can be affected by pressure associated with rapid growth. A stretch mark results when the dermis is stretched beyond its limits of elasticity, as the skin stretches to accommodate the excess pressure (American Academy of Dermatology Association, 2025). Stretch marks usually accompany rapid weight gain during puberty and pregnancy. They initially have a reddish hue but lighten over time. Other than for cosmetic reasons, treatment of stretch marks is not required. They occur most commonly over the hips and abdomen.

Corns and Calluses

Corns and calluses are hard or thick areas of skin that can be painful but are usually not serious (NHS, 2022). Corns generally present as small lumps of hard skin, while calluses present as larger patches of rough, thick skin forming most commonly on the feet, toes, and hands (NHS, 2022). For example, constant abrasion on toes, usually experienced if shoes do not fit correctly, can form a callus at the point of contact. This occurs because the basal stem cells in the stratum basale are triggered to divide more often to increase the thickness of the skin at the point of abrasion to protect the rest of the body from further damage. This is an example of a minor or local injury, and the skin manages to react and treat the problem independently of the rest of the body. Calluses can also form on your fingers if they are subject to constant mechanical stress, such as long periods of writing, playing string instruments, or video games (NHS, 2022). A corn is a specialised form of callus. Corns form from abrasions on the skin that result from an elliptical-type motion.

Skin Assessment

A routine integumentary assessment by a registered nurse in an inpatient care setting typically includes inspecting overall skin colour, inspecting for skin lesions and wounds, and palpating extremities for oedema, temperature, and capillary refill. The standard for documentation of skin assessment is within 24 hours of admission to inpatient care. Skin assessment should also be ongoing in inpatient and long-term care.

Palpation

Palpation of the skin includes assessing temperature, moisture, texture, skin turgor, capillary refill, and oedema. If erythema or rashes are present, it is helpful to apply pressure with a gloved finger to further assess for blanching (whitening with pressure). See Figure 10 for an example of palpation of an oedematous leg.

Capillary Refill

The capillary refill test is a test done on the nail beds to monitor perfusion, or the amount of blood flow to tissue. Pressure is applied to a fingernail or toenail until it turns white, indicating that the blood has been forced from the tissue under the nail. This whiteness is called blanching. Capillary refill is defined as the time it takes for colour to return to the tissue after pressure has been removed that caused blanching. If there is sufficient blood flow to the area, a pink colour should return within 2 seconds after the pressure is removed.

Subjective Assessment

Table 1. Focused interview questions regarding the integumentary system.

| Questions | Follow-up |

|

Are you currently experiencing any skin symptoms such as itching, rashes, or an unusual mole, lump, bump, or nodule? |

Use the PQRSTU method to gain additional information about current symptoms. |

| Have you ever been diagnosed with a condition such as acne, eczema, skin cancer, pressure injuries, jaundice, oedema, or lymphedema? | Please describe. |

| Are you currently using any prescription or over-the-counter medications, creams, vitamins, or supplements to treat a skin, hair, or nail condition?

|

Please describe. |

Objective Assessment

Several factors place a patient at risk of experiencing skin breakdown or developing a pressure injury. Certain body areas require observation because they are more prone to pressure injuries, such as bony prominences, skin folds, perineum, between digits of the hands and feet, and under any medical device that can be removed during routine daily care. Most pressure injuries and skin tears can be prevented by maintaining good skin hygiene, mobility, and nutrition (Department of Health, 2024).

Key Inspection Areas

There are four key areas to note during a focused integumentary assessment:

- Colour

- Temperature, moisture, and texture

- Skin turgor

- Lesions or breakdown. (Department of Health, 2024)

Colour

The skin colour is a predominant feature and is largely determined by race. Skin colour can change in relation to anatomical location (sun-exposed versus sun-protected), genetics, perfusion, hepatic obstruction or respiratory conditions (Carville, 2024). The combination of haemoglobin, oxyhaemoglobin, melanin, and carotenoids influences the colour of the skin. For example, pink-toned Caucasian skin is due to the levels of haemoglobin and oxyhaemoglobin, creating red tones due to the absorption of certain light (Carville, 2024). When assessing the skin, a healthcare provider must inspect the colour of the patient’s skin and compare findings to what has been previously recorded for the patient and what is expected for their skin tone.

Temperature, Moisture, and Texture

Fever, decreased perfusion of the extremities, and local inflammation in tissues can cause changes in skin temperature. For example, a fever can cause a patient’s skin to feel warm and sweaty (diaphoretic). Decreased perfusion of the extremities can cause the patient’s hands and feet to feel cool, whereas local tissue infection or inflammation can make the localised area feel warmer than the surrounding skin. While assessing skin temperature, also assess if the skin feels dry or moist and the texture of the skin. Skin that appears or feels sweaty is referred to as being diaphoretic.

Skin Turgor

Skin turgor is the skin’s elasticity. Its ability to change shape and return to normal may be decreased when the patient is dehydrated. To check for skin turgor, gently grasp skin on the patient’s lower arm between two fingers so that it is tented upwards, and then release. Skin with normal turgor snaps rapidly back to its normal position, but skin with poor turgor takes additional time to return to its normal position.

Lesions and Skin Breakdown

Note any lesions, skin breakdown, or unusual findings, such as rashes, petechiae, unusual moles, or burns. Be aware that unusual patterns of bruising or burns can be signs of abuse that warrant further investigation and reporting according to agency policy and state regulations.

Lifespan Considerations

|

Neonates Neonatal skin is thinner and has less sweat and fewer sebaceous glands compared with more mature skin. A neonate skin will commonly comprise of:

|

|

|

Child and Adolescent Over the course of a lifespan, the colour of an individual’s skin can regularly change. During childhood, skin will change as a result of sun exposure, trauma or infectious diseases, such as measles. As an individual enters pubescence, they will experience changes in their integumentary system including enlargement of breasts, changes to genitalia, increased sweat production and changes in the odour of body sweat, increased hair growth and increased sebaceous gland activity, particularly on the face, which can contribute to an individual developing acne (Carville, 2024). Beyond pubescent changes, other changes to the skin as an adult are generally related to lifestyle choices such as sun exposure, diet and medication use.

|

|

Older Adults Older adults have several changes associated with ageing that are apparent during assessment of the integumentary system. They often have cardiac and circulatory system conditions that cause decreased perfusion, resulting in cool hands and feet. They have decreased elasticity and fragile skin that often tears more easily. The blood vessels of the dermis become more fragile, leading to bruising and bleeding under the skin. The subcutaneous fat layer thins, so it has less insulation and padding and reduced ability to maintain body temperature. Growths such as skin tags, rough patches (keratoses), skin cancers, and other lesions are more common. Other factors that can impact skin integrity in older adults are poor nutrition, dehydration, swallowing or dental problems, balance or mobility problems, cognitive impairment, dexterity problems and medications (Department of Health, 2024).

|

Risk Factors Affecting Skin Health

Several risk factors place a patient at increased risk for altered skin health and delayed wound healing. Risk factors include impaired circulation and oxygenation, impaired immune function, diabetes, inadequate nutrition, obesity, exposure to moisture, smoking, and age. Each of these risk factors is discussed in more detail in the following subsections.

Impaired Circulation and Oxygenation

Skin, like every other organ in the body, depends on good blood perfusion to keep it healthy and functioning correctly. Cardiovascular circulation delivers important oxygen, nutrients, infection-fighting cells, and clotting factors to tissues. These elements are needed by skin, tissues, and nerves to properly grow, function, and repair damage. Without good cardiovascular circulation, skin becomes damaged. Damage can occur from poor blood perfusion from the arteries, as well as from poor return of blood through the veins to the heart. Common medical conditions that decrease cardiovascular circulation include cardiac disease, diabetes, and peripheral vascular disease (PVD). PVD includes two medical conditions arterial insufficiency and venous insufficiency.

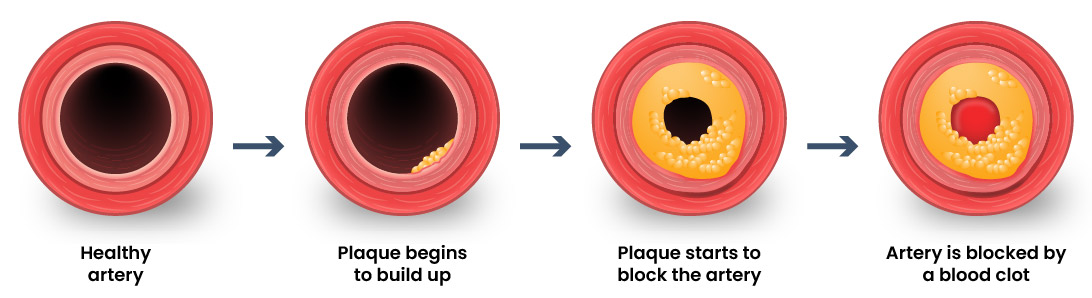

Arterial Insufficiency

Arterial insufficiency refers to a lack of adequately oxygenated blood movement in arteries to specific tissues (Zemaitis et al., 2023). Arterial insufficiency can be a sudden, acute lack of oxygenated blood, such as when a blood clot in an artery blocks blood flow to a specific area. Arterial insufficiency can also be a chronic condition caused by peripheral vascular disease (PVD). As a person’s arteries become blocked with plaque due to atherosclerosis, there is decreased blood flow to the tissues. Signs of arterial insufficiency are cool skin temperature, pale skin colour, pain that increases with exercise, and possible arterial ulcers.

When oxygenated blood flow to tissues becomes inadequate, the tissue dies. This is called necrosis. Tissue death causes the skin and tissue to become necrotic (black). Necrotic tissue does not heal, so surgical debridement or amputation of the extremity becomes necessary for healing. See Figure 11 for the different stages of arterial insufficiency.

Venous Insufficiency

Venous insufficiency occurs when the cardiovascular system cannot adequately return blood and fluid from the extremities to the heart. Venous insufficiency can cause stasis dermatitis when blood pools in the lower legs and leaks out into the skin and other tissues. Signs of venous insufficiency are oedema, a brownish-leathery appearance to skin in the lower extremities, and venous ulcers that weep fluid. Causes of venous insufficiency are hypertension, obesity, lack of exercise, family history of the condition, blood clots, and swelling of the veins (phlebitis; John Hopkins Medicine, 2025). See Figure 12 for venous insufficiency in the lower extremities.

Impaired Immune Function

Skin contributes to the body’s immune function and is also affected by the immune system. Intact skin provides an excellent first line of defence against microorganisms entering the body. This is why it is essential to keep skin intact. If skin does break down, the next line of defence is a strong immune system that attacks harmful invading organisms. However, if the immune system is not working well, the body is much more susceptible to infections. This is why maintaining intact skin, especially in the presence of an impaired immune system, is imperative to decrease the risk of infections.

Stress can cause an impaired immune response that results in delayed wound healing. Being hospitalised or undergoing surgery triggers the stress response in many patients. Medications, such as corticosteroids, also affect a patient’s immune function and can impair wound healing. When assessing a chronic wound that is not healing as expected, it is important to consider the potential effects of stress and medications.

Diabetes

Diabetes can cause wounds to develop, as well as delayed healing of wounds. This is due to elevated blood glucose causing stiffening of arterial walls, resulting in decreased circulation and tissue hypoxia. Elevated blood glucose also reduces leukocyte function, directly affecting wound healing and risk for infection (Joseph, 2019). Additionally, if patients with diabetes also have diabetic neuropathy, they do not feel pain associated with skin injuries, resulting in delayed treatment and further risk of infection. The instances of diabetes are expected to rise in conjunction with the ageing population and increased incidences of obesity, with a projected global prevalence of 4.4% by 2036 (Joseph, 2019).

Inadequate Nutrition

A healthy diet is essential for maintaining healthy skin, as well as maintaining an appropriate weight. Nutrients that are particularly important for skin health include protein; vitamins A, C, D, and E; and minerals such as selenium, copper, and zinc.

Nutritional deficiencies can have a profound impact on wound healing and must be addressed for chronic wounds to heal. Protein is one of the most important nutritional factors affecting wound healing. For example, in patients with pressure injuries, 30 to 35 kcal/kg of calorie intake with 1.25 to 1.5g/kg of protein and micronutrient supplementation are recommended daily. In addition, vitamin C and zinc have many roles in wound healing. It is important to collaborate with a dietician to identify and manage nutritional deficiencies when a patient is experiencing poor wound healing.

Obesity

Obesity has become more prevalent in the global population and is associated with diseases, such as diabetes, heart disease and metabolic syndrome. Obesity can affect wound healing due to changes in the vasculature, decreased production of growth factors, and poor-quality granulation tissue (Cotterell et al., 2024). In the same way, a balanced diet is vital for healthy skin, a healthy weight is also imperative. Obesity can change the pressure in the tissues and obese individuals usually have increased tissue pressure, due to excess adipose tissue in cutaneous skin (Cotterell et al., 2024). Obese individuals are at increased risk for fungal and yeast infections in skin folds caused by increased moisture and friction. See Figure 13 for an image of a fungal infection in the groin. Symptoms of yeast and fungal infection include redness and scaliness of the skin associated with itching.

Obese patients also are at higher risk for wound complications due to a decreased supply of oxygenated blood flow to adipose tissue. Potential complications include infection, dehiscence (separation of the edges of a surgical wound), haematoma formation, pressure injuries, and venous ulcers. Evisceration is a rare but severe complication when an abdominal surgical incision separates, and the abdominal organs protrude or come out of the incision. Nurses can educate patients about making healthy lifestyle choices to reduce obesity and the risk of dehiscence. More information on dehiscence is provided in the Introduction to Wound Care Principles chapter.

Exposure to Moisture

Healthy skin needs good moisture balance. If too much moisture (i.e., sweat, urine, or water) is left on the skin for extended periods of time, the skin will become soggy, wrinkly, and turn whiter than usual and is called maceration. A simple example of maceration is when you spend too much time in a bathtub and your fingers and toes turn white and get “pruney.” If healthy skin is exposed to moisture for an extended period of time, such as when a moist wound dressing is incorrectly applied to healthy skin, the skin will break down. This type of skin breakdown is called excoriation. Excoriation refers to the removal of the topmost surface of the skin, which results in redness and abrasions. See Figure 14 for an image of maceration.

The opposite occurs when skin lacks proper moisture. Skin becomes flaky, itchy, and cracked when it becomes too dry. Conditions such as decreased moisture in the air during cold winter months or bathing in hot water can worsen skin dryness. Dry skin, especially when accompanied by cracking, breaks the protective barrier and increases the risk of infection. It is important for nurses to apply emollient cream to patients’ areas of dry skin to maintain the protective skin barrier.

Smoking

Tobacco smoking contains numerous harmful substances, such as mutagens and carcinogens. Smoking can cause short-term and long-term issues, including yellowing of the fingers and nails, discolouration of the teeth, dry skin, baggy eyes, and deeper facial wrinkles (American Osteopathic College of Dermatology [AOCD], n.d.).

Smoking has been associated with health complications, including cancer as well as premature ageing of the skin and delayed wound healing (AOCD, n.d.). Smoking impacts the inflammatory phase of the wound healing process, which can result in poor wound healing and an increased risk of infection, wound dehiscence, and necrosis (AOCD, n.d.). This is likely due to tissue hypoxia caused by toxins in tobacco smoke such as carbon monoxide and hydrogen cyanide, as well as vasoconstriction caused by nicotine.

Age

Older adults have thin, less elastic skin that puts them at increased risk for injury. They also have an altered inflammatory response that can impair wound healing. Additionally, the elderly are at risk for poor nutrition which contributes to poor wound healing. Nurses can educate older patients about the importance of exercise for skin health and improved wound healing as appropriate.

Key Takeaways

In this chapter, we covered:

- The integumentary system is the largest and most visible organ in the body, comprised of the skin and accessory structures.

- The integumentary system has three main layers – the epidermis, the dermis and the hypodermis.

- The colour of the skin can change based on environmental factors, such as UV exposure, but skin colour is largely a result of different pigments in the cells.

- Skin cancer accounts for around 80% of newly diagnosed cases annually, and Australia has one of the highest instances of skin cancer in the world.

- A routine skin assessment by a registered practitioner typically includes inspecting overall skin colour, checking for skin lesions or wounds, and palpating extremities for oedema, temperature, and capillary refill.

- The integumentary system experiences significant changes throughout a lifetime, and the skin of a neonate differs from that of an older adult.

- Risk factors such as diabetes, impaired nutrition and smoking can place a patient at increased risk for altered skin health and delayed wound healing.

References

American Academy of Dermatology Association. (2025). Stretch marks: Why they appear and how to get rid of them. https://www.aad.org/public/cosmetic/scars-stretch-marks/stretch-marks-why-appear

American Osteopathic College of Dermatology. (n.d.). Smoking and its effects on skin. https://www.aocd.org/page/Smoking#

Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy. (2024). Eczema (Atopic Dermatitis). https://www.allergy.org.au/patients/skin-allergy/eczema

Cancer Council. (2024). Types of cancer: Skin cancer. https://www.cancer.org.au/cancer-information/types-of-cancer/skin-cancer

Carville, K. (2024). Changes in the integument across the lifespan. Wound Practice and Research, 32(1), 11-16. https://doi.org/10.33235/wpr.32.1.11-16

Cotterell, A., Griffin, M., Downer, M. A., Parker, J. B., Wan, D., Longaker, M. T. (2024). Understanding wound healing in obesity. World Journal of Experimental Medicine, 14(1). https://doi.org/10.5493/wjem.v14.i1.86898

Department of Health. (2024). Scabies. Victorian Government. https://www.health.vic.gov.au/infectious-diseases/scabies

John Hopkins Medicine. (2025). Chronic venous insufficiency. The John Hopkins University. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/chronic-venous-insufficiency

Joseph, A. (2019). Nutrition in wound healing for adults with diabetes. Australian Diabetes Educator, 22(3). https://ade.adea.com.au/nutrition-in-wound-healing-for-adults-with-diabetes-a-practice-update/

National Health Service. (2022). Corns and calluses. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/corns-and-calluses/

National Health Service. (2023). Keloid scars. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/keloid-scars/

Smith, V., & Walton, S. (2011). Treatment of facial basal cell carcinoma: A review. Journal of Skin Cancer, 2011, 380371. https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/380371

World Health Organization. (2024). Burns. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/burns

Zemaitis, M. R., Boll, J. M., & Dreyer, M. A. (2023). Peripheral arterial disease. In W. B. Ackley, T. S. Adolphe, T. C Aeby, N. R. Aeddula, S. Agadi, P. Agasthi, S. Ahmad, A. Ahmed, F. W. Ahmed, I. Ahmed, R. A Ahmed, S. W. Ahmed, A. M Akanmode, R. Akella, S. M. Akram, Y. Al Khalili, E. Al Zaabi, M. H. Alahmadi, G. Alexander, … H. Zulfiqar (Eds). StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved February 19, 2025 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430745

Chapter Attribution

This chapter has been adapted in parts from:

Anatomy and physiology 2e (2022) by J. Gordon Betts, Kelly A. Young, James A. Wise, Eddie Johnson, Brandon Poe, Dean H. Kruse, Oksana Korol, Jody E. Johnson, Mark Womble and Peter DeSaix, OpenStax, is used under a CC BY licence.

Basic integumentary concepts in Nursing skills 2e (2023) by Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN), Chippewa Valley Technical College, is used under a CC BY 4.0 licence.

Common integumentary conditions in Nursing skills 2e (2023) by Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN), Chippewa Valley Technical College, is used under a CC BY 4.0 licence.

Integumentary assessment in Nursing skills 2e (2023) by Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN), Chippewa Valley Technical College, is used under a CC BY 4.0 licence.

Integumentary basic concepts in Nursing skills 2e (2023) by Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN), Chippewa Valley Technical College, is used under a CC BY 4.0 licence.

Media Attributions

- Layers of the Skin © OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Layers of the Dermis © OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Skin Pigmentation © OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Hair Follicles is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Nail Structure © OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Eccrine Gland © OpenStax College is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Basal Cell Carcinoma © National Cancer Institute is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Squamous Cell Carcinoma © Bruce Blaus is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Melanoma © OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Eczema on Arms © Jambula is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Acne © Roshu Bangal is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Burns Rule Of Nines © J. Gordon Betts, Kelly A. Young, James A. Wise, Eddie Johnson, Brandon Poe, Dean H. Kruse, Oksana Korol, Jody E. Johnson, Mark Womble & Peter DeSaix adapted by Eileen Siddins is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Oedema Example © James Heilman is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Artery Blockage © Eileen Siddins is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Chronic Venous Insufficiency © James Heilman is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Tinea Cruris Fungal Infection © Robertgascoin is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Trench Foot (Macerated Skin) © Mehmet Karatay is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

The thin, uppermost layer of skin

The inner layer of skin with connective tissue, blood vessels, sweat glands, nerves, hair follicles, and other structures

The layer of skin beneath the dermis composed of connective tissue and used for fat storage

Skin pigment produced by melanocytes scattered throughout the epidermis

An allergic reaction to the skin, causing a dry and itchy rash

A skin disturbance that typically occurs on areas of the skin that are rich in sebaceous glands, such as the face and back

A parasitic skin infection caused by mites, that is highly contagious

The rubbing of skin against a hard object, such as the bed or the arm of a wheelchair. This rubbing causes heat that can remove the top layer of skin and often results in skin damage

New connective tissue in a healing wound with new, fragile, thin-walled capillaries

Swelling

A red colour of the skin

To make white or pale by applying pressure

A yellowing of the skin or sclera caused by underlying medical conditions

A type of swelling that occurs when lymph fluid builds up in the body’s soft tissues due to damage to the lymph system

Excessive, abnormal sweating

An area of abnormal tissue

Tissue death

The separation of a surgical incision

A condition that occurs when skin has been exposed to moisture for too long causing it to appear soggy, wrinkled, or whiter than usual

Redness and removal of the surface of the topmost layer of skin, often due to maceration or itching

The second stage of healing when vasodilation occurs to move white blood cells into the wound to start cleaning the wound bed