Introduction to Wound Care Principles

Kate Hurley and Sandra Dash

Learning Outcomes

In this chapter you will learn how to:

- Identify common wound types and recognise the different phases of wound healing

- Recognise common wound complications and the factors that can affect wound healing

- Complete a wound assessment and document findings to manage external and internal factors that can compromise wound healing

- Identify and apply wound care dressings commonly used in practice.

Introduction

Wound healing is a complex physiological process that restores function to skin and tissue that have been injured. The healing process is affected by several external and internal factors that either promote or inhibit healing. When providing wound care to patients, nurses, in collaboration with other members of the health care team, assess and manage external and internal factors to provide an optimal healing environment.

Complex wounds often require care by specialists. Certified wound care nurses assess, treat, and create care plans for patients with complex wounds, ostomies, and incontinence conditions. They act as educators and consultants to staff nurses and other healthcare professionals. This chapter will discuss wound care basics for entry-level nurses.

Basic Concepts Related to Wounds

Phases of Wound Healing

When skin is injured, there are four phases of wound healing that take place: haemostasis, inflammatory, proliferative, and maturation. The phases of wound healing are described below.

When performing dressing changes, it is essential for the nurse to protect this granulation tissue and the associated new capillaries. Healthy granulation tissue appears pink, moist, and is painless to the touch due to the new capillary formation. Unhealthy granulation tissue is dark red and painful. It bleeds easily with minimal contact and may be covered by shiny white or yellow fibrous tissue referred to as biofilm that must be removed because it impedes healing.

Complications in Wound Healing

Haematoma

A haematoma is an area of blood that collects outside of the larger blood vessels. A haematoma is more severe than ecchymosis (bruising) that occurs when small veins and capillaries under the skin break. The development of a haematoma at a surgical site can lead to infection and wound dehiscence.

Infection

A break in the skin allows bacteria to enter and begin to multiply. Microbial contamination of wounds can progress from localised infection to systemic infection, sepsis, and subsequent life- and limb-threatening infection. Signs of a localised wound infection include redness, warmth, increased drainage and tenderness around the wound. Signs that a systemic infection is developing and requires urgent medical management include the following:

- Fever over 38° C

- Overall malaise (lack of energy and not feeling well)

- Change in level of consciousness/increased confusion

- Increasing or continual pain in the wound

- Expanding redness or swelling around the wound

- Loss of movement or function of the wounded area.

Dehiscence

Dehiscence refers to the separation of the edges of a surgical wound. To prevent wound dehiscence, surgical patients must follow all post-op instructions carefully. The patient must move carefully and protect the skin from being pulled around the wound site. A dehisced wound can appear fully open where the tissue underneath is visible, or it can be partial where just a portion of the wound has opened. Wound dehiscence is always a risk in a surgical wound, but the risk increases if the patient is obese, smokes, or has other health conditions, such as diabetes, that impact wound healing. Additionally, the location of the wound and the amount of physical activity in that area can also increase the chances of wound dehiscence. See Figure 2 for an image of dehiscence in an abdominal surgical wound in a 50-year-old obese female with a history of smoking and malnutrition.

Wound dehiscence can occur suddenly, especially in abdominal wounds when the patient is coughing or straining. Evisceration is a rare but severe surgical complication when dehiscence occurs, and the abdominal organs protrude out of the incision. Signs of impending dehiscence include redness around the wound margins and increasing drainage from the incision. Suture breakage can be a sign that the wound has minor dehiscence or is about to dehisce and the wound will also likely become increasingly painful.

Assessing Wounds

Wounds should be assessed and documented at every dressing change. Wound assessment should include the following components:

- Anatomic location

- Type of wound (if known)

- Degree of tissue damage

- Wound bed

- Wound size

- Wound edges and surrounding skin

- Signs of infection

- Amount and type of exudate

- Pain.

These components are further discussed in the following sections.

Anatomic Location and Type of Wound

The location of the wound should be documented using correct anatomical terms and numbering. In practice, a wound care assessment document will be used to chart the appearance of the wound and the required dressing regime. The wound care assessment document would record information such as a description of the wound, a description of the surrounding skin, the position of the wound, and the type and amount of exudate. Clear and concise documentation of a wound and relevant features, means the wound is consistently monitored and treated appropriately.

The location of a wound also provides information about the cause and type of a wound. For example, a wound over the sacral area of an immobile patient is likely a pressure injury, and a wound near the ankle of a patient with venous insufficiency is likely a venous ulcer. For successful healing, different types of wounds require different treatments based on the cause of the wound.

Wound Base

Assess the colour of the wound base. Healthy granulation tissue appears pink due to the new capillary formation, and it is moist, and painless to the touch. Conversely, unhealthy granulation tissue is dark red and painful. It bleeds easily with minimal contact and may be covered with biofilm. The appearance of slough (yellow) or eschar (black) in the wound base should be documented and communicated to the health care provider because it likely will need to be removed for healing.

Type and Amount of Exudate

The colour, consistency, and amount of exudate should be assessed and documented at every dressing change. The amount of drainage from wounds is categorised as scant, minimal, moderate, or large. Use the following descriptions to select the appropriate terms:

The type of wound drainage should be described using medical terms such as serosanguinous, sanguineous, serous, or purulent.

If a moderate to large amount of exudate is expected, a surgical drain will be placed into the wound bed during a procedure. These drains allow the exudate to drain away from the wound, allowing wound healing to take place. There are many different types of wound drains in practice, and these are generally removed a few days after a surgical procedure.

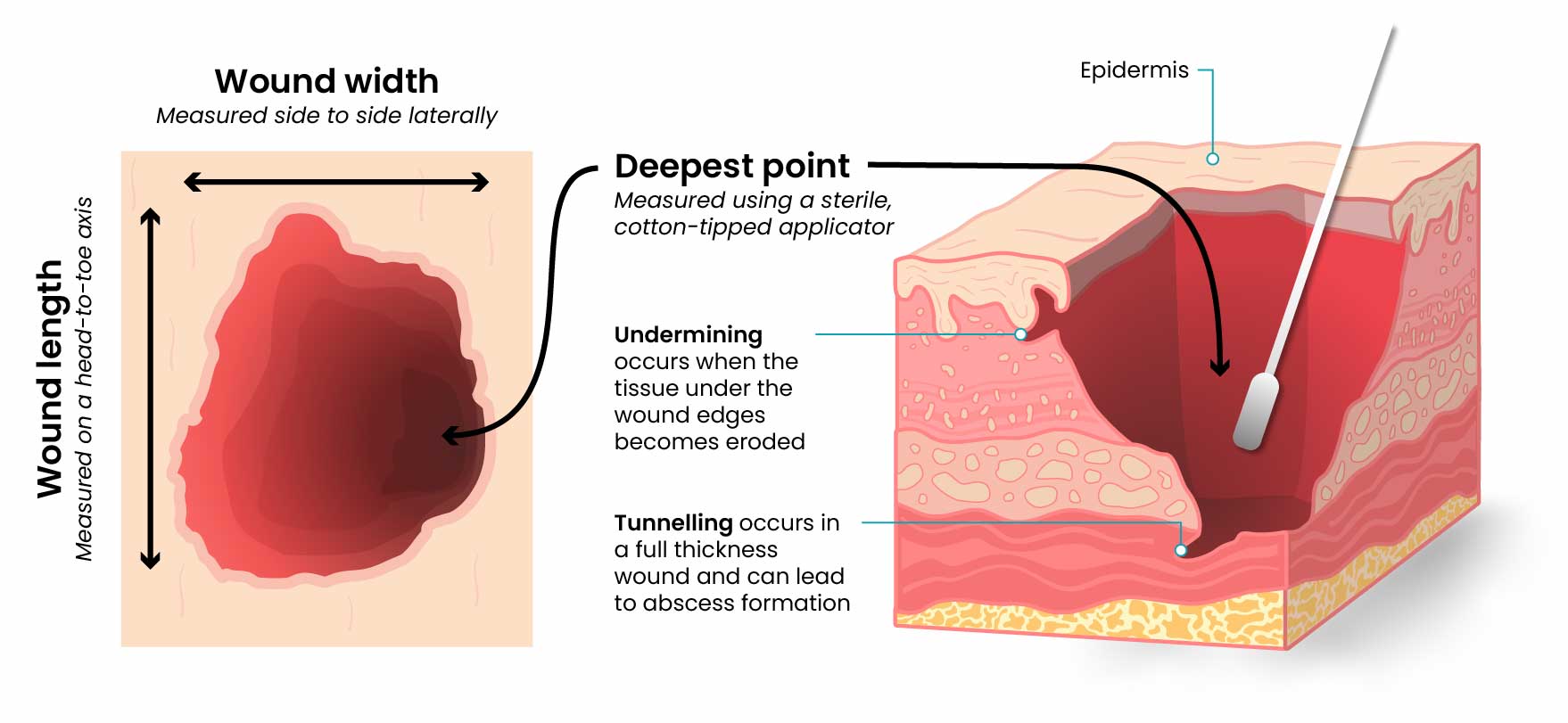

Wound Size

Wounds should be measured on admission and during every dressing change to evaluate for signs of healing. Accurate wound measurements are vital for monitoring wound healing. Measurements should be taken in the same manner by all clinicians to maintain consistent and accurate documentation of wound progress. This can be difficult to accomplish with oddly shaped wounds because there can be confusion about how to consistently measure them. Wounds should be described by length by width, with the length of the wound based on the head-to-toe axis. The width of a wound should be measured from side to side laterally. If a wound is deep, the deepest point of the wound should be measured to the wound surface using a sterile, cotton-tipped applicator.

Tunnelling

Tunnelling can occur in a full thickness wound that can lead to abscess formation. The depth of tunnelling can be measured by gently probing the tunnelled area with a sterile, cotton-tipped applicator from the wound base to the end of the tract. When probing a tunnel, it is imperative to not force the swab but only insert it until resistance is felt to prevent further damage to the area. The location of the tunnel in the wound should be documented using the analogy of a clock face, with 12:00 pointing toward the patient’s head.

Undermining

Undermining occurs when the tissue under the wound edges becomes eroded, resulting in a pocket beneath the skin at the wound’s edge. Undermining is measured by inserting a probe under the wound edge directed almost parallel to the wound surface until resistance is felt. The amount of undermining is the distance from the probe tip to the point at which the probe is level with the wound edge. The analogy of a clock face, with 12:00 pointing toward the patient’s head, is used to identify the area of undermining.

Wound Edges and Periwound Skin

If the wound is healing by primary intention, it should be documented if the wound edges are well-approximated (closed together) or if there are any signs of dehiscence. The skin outside the outer edges of the wound called the periwound skin, provides information related to wound development or healing. For example, when a wound has excess exudate, it can macerate the periwound skin, giving it a waterlogged appearance that is light grey in colour. See Figure 4 for an image of erythematous periwound with partial dehiscence.

Signs of Infection

Wounds should be continually monitored for signs of infection. Signs of localised wound infection include erythema, induration, pain, oedema, purulent , exudate (yellow or green drainage), and wound odour. Signs of infection should be reported to the medical team and a swab of the wound site should be conducted.

Pain

The intensity of pain that a patient is experiencing with a wound should be assessed and documented. If a patient experiences pain during dressing changes, it should be managed with the administration of pain medication before scheduled dressing changes. Be aware that the degree of pain may not correlate to the extent of tissue damage. For example, skin tears are often painful because the nerve endings are exposed in the dermal layer, whereas patients with severe diabetic ulcers on their feet may experience little or no pain because of existing neuropathic damage.

Types of Wound Healing

Primary Intention

There are three types of wound healing: primary intention, secondary intention, and tertiary intention. Healing by primary intention means that the wound is sutured, stapled, glued, or otherwise closed so the wound heals beneath the closure. This type of healing occurs with clean-edged lacerations or surgical incisions, and the closed edges are referred to as approximated. See Figure 5 for an image of a surgical wound healing by primary intention.

Secondary Intention

Secondary intention occurs when the edges of a wound cannot be approximated (brought together), so the wound fills in from the bottom up by the production of granulation tissue (e.g. pressure injuries). Wounds that heal by secondary intention are at higher risk for infection and must be protected from contamination. See Figure 6 for an image of a wound healing by secondary intention.

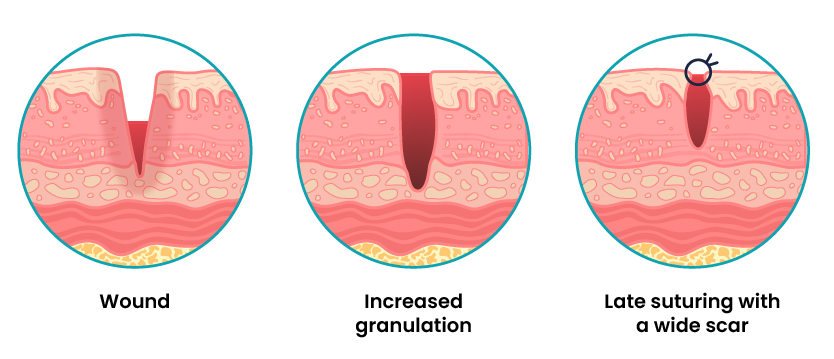

Tertiary Intention

Tertiary intention wound healing occurs when there is a delay to primary wound healing or primary wound healing has not been successful. The treatment team make the decision to stop or skip secondary intention, as the wound often requires cleaning, remodelling and/or debridement before being mechanically closed. See Figure 7 for an image of a wound healing by tertiary intention.

Wound Closures

Lacerations and surgical wounds are typically closed with sutures or staples. See Figure 8 for an image of sutures and Figure 9 for an image of staples. Sutures and staples generally stay in place until the wound has healed underneath and can be removed with an order provided by the medical team.

Common Types of Wounds

It is important to understand different types of wounds when providing wound care because each type of wound has different characteristics and treatments. Treatments that may be helpful for some wounds, can be harmful for other types of wounds. The most common types of wounds include skin tears, venous ulcers, arterial ulcers, diabetic foot wounds, and pressure injuries.

Skin Tears

Skin tears are wounds caused by mechanical forces such as shear, friction, or blunt force. They typically occur in the fragile, nonelastic skin of older adults or in patients undergoing long-term corticosteroid therapy. Skin tears can be caused by the simple mechanical force used to remove an adhesive bandage or from friction as the skin brushes against a surface. Skin tears occur in the epidermis and dermis but do not extend through the subcutaneous layer. The wound bases of skin tears are typically fragile and bleed easily.

Venous Ulcers

Venous ulcers are caused by insufficient circulation, or a lack of blood return to the heart causing the pooling of fluid in the veins of the lower legs. The resulting elevated hydrostatic pressure in the veins causes fluid to seep out, macerate the skin, and cause venous ulcerations.

Venous ulcers typically occur on the medial lower leg and have irregular edges due to the maceration. There is often discolouration of the lower legs, due to blood pooling and leakage of iron into the skin called hemosiderin staining. For venous ulcers to heal, compression dressings must be used, along with multilayer bandage systems, to control oedema and absorb large drainage. See Figure 10 for an image of a venous ulcer.

Arterial Ulcers

Arterial ulcers are caused by a lack of blood flow and decreased oxygenation to tissues. They typically occur in the distal areas of the body such as the feet, heels, and toes. Arterial ulcers have well-defined borders with a “punched out” appearance where there is a localised lack of blood flow. They are typically painful due to the lack of oxygenation in the area. The wound base may become necrotic due to tissue death from ischemia. Wound dressings must maintain a moist environment, and treatment must include the removal of necrotic tissue. In severe arterial ulcers, vascular surgery may be required to reestablish blood supply to the area. See Figure 11 for an image of an arterial ulcer on a foot.

Diabetic Ulcers

Diabetic ulcers are also called neuropathic ulcers because peripheral neuropathy is commonly present in patients with diabetes. Peripheral neuropathy is a medical condition that causes decreased sensation of pain and pressure, especially in the lower extremities. Diabetic ulcers typically develop on the plantar aspect of the feet and toes of a patient with diabetes due to a lack of sensation of pressure or injury. Wound healing is compromised in patients with diabetes due to the disease process. In addition, there is a higher risk of developing an infection that can reach the bone requiring amputation of the area. To prevent diabetic ulcers from occurring, individuals need to care for their feet, including well-fitting shoes. See Figure 12 for an image of a diabetic ulcer.

Factors Affecting Wound Healing

Multiple factors affect a wound’s ability to heal and are referred to as local and systemic factors. Local factors refer to factors that directly affect the wound, whereas systemic factors refer to the overall health of the patient and their ability to heal. Local factors include localised blood flow and oxygenation of the tissue, the presence of infection or a foreign body, and venous sufficiency. Venous insufficiency is a medical condition where the veins in the legs do not adequately send blood back to the heart, resulting in a pooling of fluids in the legs. Systemic factors that affect a patient’s ability to heal include nutrition, mobility, stress, diabetes, age, obesity, medications, alcohol use, and smoking. When a nurse is caring for a patient with a wound that is not healing as anticipated, it is important to assess the wound for potential impact of these factors:

Wound Therapy

Wound therapy is often prescribed by a multidisciplinary team that can include the provider, a wound care nurse, a dietician, and the bedside nurse who performs dressing changes. Topical dressings should be selected that create an environment conducive to healing the specific type of wound and its causes. It is important to perform the following actions when providing wound care. Each of these objectives is further discussed below.

Wound Dressings

Common Wound Dressings

Wound dressings should be selected based on the type of the wound, the cause of the wound, and the characteristics of the wound. A specialised wound care nurse should be consulted, when possible, for appropriate selection of dressings for chronic wounds. Common wound care dressings are films, sterile gauze, foam, and alginate/hydrofibers.

Films: an adherent dressing that is permeable to gas, but impermeable to bacteria and fluid. This type of dressing is useful for superficial wounds with minimum exudate. This dressing can stay in situ for 1–4 days.

Sterile gauze: a nonadherent dressing used on moderate to highly exudative wounds. This dressing type is generally nontraumatic to the wound bed and promotes a moist wound environment for healing. This dressing can stay in situ for 1–4 days.

Foam: a nonadherent dressing used on moderate to high exudative wounds. Foam dressings are nontraumatic to the wound bed and promote a moist wound environment for healing. This dressing can stay in situ for up to 7 days.

Alginate/hydrofibers: a nonadherent dressing used on highly exudative wounds. Alginate and hydrofibers are nontraumatic to the wound bed and highly absorptive, meaning they can be used to pack a wound if required. This dressing can stay in situ for up to 2 days.

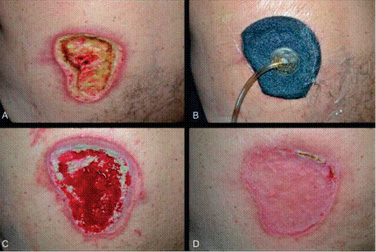

Negative Pressure Wound Therapy

Negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT), is commonly used to treat complex wounds which are non-healing or at risk of non-healing (Zaver & Kankanalu, 2023). NPWT is a broad term to describe a system that optimises healing by applying pressure to help reduce inflammatory exudate and promote the growth of granulation tissue (Zaver & Kankanalu, 2023). There are numerous different NPWT appliances available. In Australia, a wound vacuum is commonly used for acute, complex wounds.

Wound Vacuum

A common NPWT appliance utilised in Australia is a wound vacuum. The term wound vacuum refers to a device used with special foam dressings and suctioning to remove fluid and decrease air pressure around a wound to assist in healing. The foam is placed into an open wound and sealed with a thin film. The film has an opening that rubber tubing fits through to connect to a vacuum pump. Once connected, the vacuum pump removes fluid from the wound while also helping to pull the edges of the wound together. This dressing is typically insitu 24 hours a day while the wound is healing. See Figure 14 Wound healing using a wound vacuum system.

Key Takeaways

In this chapter, we covered:

- Four key phases to wound healing occur over a period of days to weeks – haemostasis, inflammation, proliferation and maturation.

- A wound assessment should be completed and documented at each dressing change, checking components such as location of the wound, type of wound, degree of tissue damage, wound bed, size of the wound, health of the wound edges and surrounding skin, signs of infection, amount and type of exudate and pain.

- The level of type of exudate from a wound can vary, and the colour, consistency and amount of exudate should be assessed and documented at every dressing change.

- There are three main types of wound healing – primary intention (simple suture line), secondary intention (lower leg ulcer) and tertiary intention (medical closure).

- Many factors can affect or delay wound healing, including smoking, stress, nutritional status, obesity and alcohol consumption.

References

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. (2018). Pressure injury. safetyandquality.gov.au/sites/default/files/2019-05/saq7730_hac_factsheet_pressureinjury_longv2.pdf

Barakat-Johnson, M., Ryan, H., Brooks, M. et al. (2023). A quick guide to pressure injury management. Wounds International. https://woundsinternational.com/supplements/a-quick-guide-to-pressure-injury-management/

Jans, C. (2018). Skin integrity and wound care. In A. Berman, S. Snyder, T. Levett-Jones, T. Dwyer, M. Hales, N. Harvey, L. Moxham, T. Langtree, B. Parker, K. Reid-Searl, & D. Stanley. Kozier and Erb’s Fundamentals of Nursing: Concepts, process and practice. Volume 2 (4th ed., Vol 2, pp. 926–962). Pearson.

Latimer, S., Shaw, J., Hunt, T., Mackrell, K., & Gillespie, B. (2019). Kennedy terminal ulcers: A scoping review. Journal of Hospice and Palliative Nursing 21(4): 257–263. https://doi.org/10.10997/NJH.0000000000000563

Shank, J. E. (2018). The Kennedy terminal ulcer: Alive and well. The Journal of the American College of Clinical Wound Specialist, 8(1–3), 54–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jccw.2018.02.002

Zaver, V., & Kankanalu, P. (2023). Negative pressure wound therapy. In W. B. Ackley, T. S. Adolphe, T. C. Aeby, N. R. Aeddula, S. Agadi, P. Agasthi, S. Ahmad, A. Ahmed, F. W. Ahmed, I. Ahmed, R. A. Ahmed, S. W. Ahmed, A. M. Akanmode, R. Akella, S. M. Akram, Y. Al Khalili, E. Al Zaabi, M. H. Alahmadi, G. Alexander, … H. Zulfiqar (Eds). StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved November 4, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK576388/

Chapter Attributions

This chapter has been adapted in parts from:

Nursing Fundamentals 2e (n.d.) by Open Resources for Nursing, Chippewa Valley Technical College, is used under a CC BY licence.

Nursing Skills 2e (2023) by Open Resources for Nursing, Chippewa Valley Technical College, is used under a CC BY licence.

Media Attributions

- Haematoma © Glen Bowman is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Bogota Bag © Suarez-Grau, J. M., Guadalajara Jurado, J. F., Gómez Menchero, J., Bellido Luque, J. A. is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Measuring Wounds © Eileen Siddins is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Post-Operative Wound (Periwound) © Open Resources for Nursing is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Primary Intention Wound Healing © SteinsplitterBot is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Secondary Intention Wound Healing © Sansea2 is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Tertiary Intention Wound Healing © Eileen Siddins is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Sutures © Wikip2011 is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Staples © Llywrch is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Venous Ulcer © DocElisa is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Arterial Ulcer © Stevenfruitsmaak is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Diabetic Ulcer © John Campbell is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Wound Debridement © Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN) is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Wound Vacuum © WisTech Open is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

A condition that occurs when skin has been exposed to moisture for too long causing it to appear soggy, wrinkled, or whiter than usual

A red colour of the skin

A thickening or hardening of the soft tissue in the skin

Swelling

Fluid that oozes from a wound

Dead tissue that is black

A reduction or restriction in blood flow to a part of the body