Non-Parenteral Medication Administration

Leisa Sanderson; Penelope Coogan; and Tracey Gooding

Learning Outcomes

In this chapter, you will learn how to:

- Describe the nurse’s responsibilities in ensuring safe and effective medication administration

- Identify different routes of medication administration, including enteral, topical, and inhaled

- Recognise common medication formulations and their appropriate administration techniques

- Demonstrate safe practices for administering medications via oral, sublingual, buccal, gastric tube, topical, and inhalation routes.

Medication Administration

Medications are available in various forms and can be administered through multiple routes. The choice of route depends on the medication’s properties, the intended therapeutic effect, and the patient’s physical and cognitive condition. It is the responsibility of the registered nurse to assess these factors and ensure the medication is administered via the most appropriate route for the patient’s current needs.

Routes of administration can be categorised as enteral, topical, or parenteral. This chapter will outline common medication formulations, administration considerations and best practice procedures for safe and effective medication administration in relation to enteral and topical methods.

The Nurse’s Role in Medication Administration

Registered nurses who prescribe or administer medications are professionally accountable for ensuring safe and effective practice. This responsibility requires comprehensive knowledge of the medication, including its indications, therapeutic and adverse effects, and potential interactions (Frotjold & Bloomfield, 2021).

Prior to administration, the nurse must assess the patient’s condition and determine the clinical need for the medication. Safe medication practices must be followed throughout the process, including accurate preparation, correct administration, and adherence to legal and ethical standards. Following administration, the nurse must evaluate the patient’s response and document the outcome appropriately (Frotjold & Bloomfield, 2021).

Therapeutic Actions of Medications

Formulations of Oral Medication

Medications are supplied in a solid or liquid form. Within each form, there are several different formulation types, each with its own administration considerations. The nurse must be familiar with the various formulations and the techniques associated with each preparation to ensure that safe medication administration practices are followed.

Enteral Administration

Enteral administration pertains to medications administered via the gastrointestinal tract. Enteral administration includes oral, buccal, sublingual, and gastric administrations that enter directly into the stomach or intestines through feeding tubes.

Oral Medication Administration

Oral administration is the most common route for medication delivery due to its simplicity, convenience, and non-invasive nature. Medications taken orally (PO) are ingested by mouth and may be absorbed at various sites along the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. This route typically has a slower onset of action but provides a more prolonged effect compared to other routes. The typical onset is 30 to 60 minutes.

Before administering oral medications, the nurse must assess the patient for any contraindications, such as vomiting, gastric or intestinal suction, or an impaired level of consciousness that affects the ability to swallow. If dysphagia is present, consideration may be given to crushing tablets, ideally in consultation with a speech pathologist. Crushed tablets are often mixed with a soft food such as custard or stewed fruit, provided this aligns with the patient’s dietary requirements and the medication’s formulation.

However, not all medications are suitable for crushing. Enteric-coated and modified-release formulations must never be altered, as doing so can compromise their efficacy and safety. Suitability for crushing should be verified using a reliable source, such as the Don’t Rush to Crush handbook or through consultation with a pharmacist.

The absorption of oral medications can be influenced by several factors, including gastric pH, the presence of food, absorption through the small bowel, and metabolism by liver enzymes, also known as first-pass drug metabolism (Kim & De Jesus, 2023). These variables can affect the onset, intensity, and duration of the medication’s action and should be considered when evaluating the patient’s response.

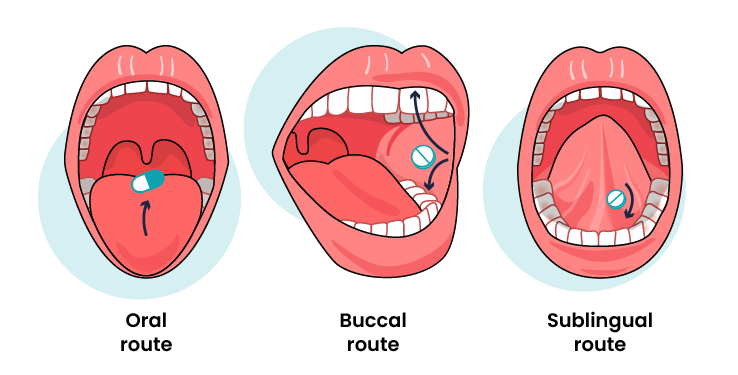

Sublingual Medication Administration

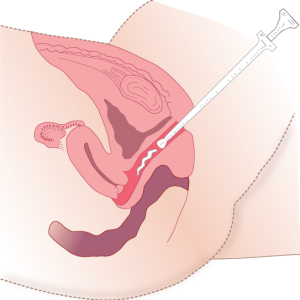

Medications ordered to be administered via the sublingual route are placed under the tongue and left to dissolve (Figure 1). These medications dissolve rapidly into the bloodstream for fast absorption and therefore are not affected by hepatic first-pass metabolism. Due to the rapid absorption, medications administered via this route are typically used to treat emergencies. Glyceryl trinitrate is one such medication that is commonly given via this route by tablet or spray to relieve those experiencing cardiac-related chest pain. It is important to educate the patient not to chew or swallow the medication and to let it completely dissolve under the tongue. Food and drink may also affect the absorption of sublingual medications; therefore, the patient should also be advised to refrain from eating or drinking until the tablet is completely dissolved.

Buccal Medication Administration

Medications ordered to be administered via the buccal route are placed between the gum and the cheek and left until it dissolves (Figure 1). These medications dissolve rapidly into the bloodstream for fast absorption and are not affected by hepatic first-pass metabolism. Like sublingual medications, the patient should be advised to not swallow, chew or take it with water, and should refrain from eating or drinking until the tablet is completely dissolved. To avoid mucosal irritation, the patient should be taught to alternate cheeks with each dose (Bullock & Manias, 2022).

Administering an Oral Medication

Solid medications are typically supplied in either blister packs or bottles. Blister packs are usually single-use and protect individual doses from contamination until they are opened at the patient’s bedside. Bottles, on the other hand, contain multiple doses and are considered multidose packaging.

When dispensing medications, tablets and capsules should be handled as little as possible to reduce the risk of contamination. To dispense from a bottle:

- Pour the required number of tablets or capsules into the bottle cap

- Transfer them from the cap into a clean medication cup

- Only break scored tablets and do so using a pill cutter or by snapping them with gloved fingers.

For blister packs:

- Hold the packaging directly over a clean medication cup

- Push the tablet or capsule through the foil into the cup, avoiding direct contact.

Typically, liquid and suspension medications are prepared using an oral syringe, dosing cup, medication dropper, or medication spoon. Household spoons, such as flatware, are not recommended for measuring medications because they are not uniform in size.

When administering liquid medications, take care to avoid contaminating the bottle cap. Follow these steps:

- Hold the medication cup at eye level

- Pour the liquid to the desired level, ensuring the measurement is taken at the base of the meniscus for accuracy

- For unit-dose liquids or when measuring volumes less than 10 mL, use an oral syringe (without a needle) for precise dosing.

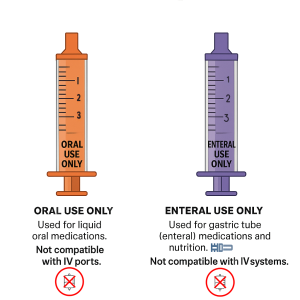

Safety Alert: Enteral Syringe Identification

|

To prevent accidental intravenous (IV) administration, colour-coded syringes are used for specific routes of medication delivery. Orange syringes are designated for oral liquid medications, while purple syringes are used for enteral (gastric tube) medications and nutrition; both are incompatible with IV systems. These visual and physical safeguards help ensure medications are administered safely and correctly |

Oral, Sublingual, Buccal Medication Administration Procedure

Medication Administration via Gastric Tubes

When a patient is unable to swallow safely, medications may be administered via a gastric tube, delivering the medication directly into the stomach or small intestine. This route is used only when oral administration is not feasible. A patient with a gastric tube who can swallow may still take the medication by mouth.

Gastric tubes include:

Nasogastric (NG) tube – inserted through the nose into the stomach

Gastrostomy (G) tube – inserted directly into the stomach through the abdominal wall

Jejunostomy (J) tube – inserted into the jejunum (part of the small intestine)

The location of the tube is a critical consideration, as it influences the absorption and effectiveness of the medication. For example, medications designed for gastric absorption may not be suitable for jejunal administration. In such cases, an alternative formulation or route may be required.

Additional factors to consider include the patient’s fasting status. Patients who are nil by mouth (NBM) due to fasting or medical orders still require the same precautions as those receiving oral medications, including assessment of the medication’s suitability and potential interactions.

Not all oral medications are intended to be administered via a gastric tube; therefore, careful consideration should be given to the compatibility of the medication to be administered via this method. Medications administered via a gastric tube need to be supplied in a liquid form, if available, or crushed and diluted if supplied in a solid form. It is also recommended that medications intended to be administered via a gastric tube be specifically ordered as such. The ordered route should state to administer the medication via the NG, PEG (Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy), NJ or PEJ (Percutaneous endoscopic jejunostomy) rather than PO.

Gastric Tube Medication Administration Procedure

Topical Administration

Topical medications are applied directly to a specific area of the body to produce a local or, in some cases, systemic effect. While commonly associated with the skin, topical administration also includes applications to mucous membranes and body cavities, such as the eyes, ears, nose, rectum, and vagina.

These medications are designed to act at or just beneath the site of application. For example, skin preparations may act locally within the dermis or be absorbed into the bloodstream for systemic effects. Similarly, topical treatments can be used in the gastrointestinal tract (e.g., oral gels) or during surgical procedures (e.g., antibiotics applied to body cavities) (Bullock & Manias, 2022).

Topical routes also include inhalation therapies, where medications are delivered directly to the respiratory mucosa for rapid local or systemic action.

Skin

Topical medications are applied directly to the skin or mucous membranes to produce local or systemic effects. They may be administered through various methods, including:

- Direct application (e.g., creams, ointments)

- Transdermal patches or discs

- Medicated baths or soaks

- Moist dressings.

These applications may remain in place for as little as 12 hours or up to seven days, depending on the medication and therapeutic goal.

Types of Topical Skin Preparations

Safety Considerations for Transdermal Patches

|

The following section outlines important safety aspects to be considered when using transdermal patches, including how to prevent overdose, avoid burns or injury from metal components, and to ensure correct disposal. |

Topical – Skin – Medication Administration Procedure

Eye (Ophthalmic) Administration

Ophthalmic medications are commonly used to treat a variety of eye conditions and are available in the form of drops or ointments. Eye drops are typically packaged in non-drip plastic containers, while ointments are supplied in small tubes. These medications must be isotonic to avoid causing discomfort or irritation upon application. Eye drops may be aqueous or oily solutions or suspensions and are instilled directly into the conjunctival sac (Bullock & Manias, 2022). Ointments are applied along the lower eyelid and provide longer contact time with the eye surface. In some cases, eye irrigation is used to flush out foreign bodies or chemical contaminants using large volumes of saline. The volume and duration of irrigation depend on the nature of the contaminant and the severity of exposure.

Ear (Otic) Administration

Ear medications are typically administered as oily solutions to ensure they coat the ear canal effectively (Bullock & Manias, 2022). These medications may include antibiotics, analgesics, wax softeners, or irrigation fluids used to remove debris or wax buildup. It is important that ear drops, and irrigation fluids are at room temperature before administration, as cold solutions can cause vertigo or nausea due to the sensitivity of the inner ear structures (Bullock & Manias, 2022). Medications are instilled into the outer ear canal, with the tympanic membrane acting as a barrier to the middle and inner ear. If the tympanic membrane is perforated, instillation should only be performed using aseptic non-touch technique to prevent infection or further damage.

Nasal Administration

Nasal medications are administered via sprays, drops, or medicated packing and are commonly used to treat conditions such as nasal congestion, allergies, and sinus infections. Decongestant sprays and drops are the most frequently used forms. These medications must be isotonic to avoid irritation of the nasal mucosa. Oil-based solutions are generally avoided, as they can impair the function of the nasal cilia (Bullock & Manias, 2022). Nasal medications are typically administered using a clean technique to prevent contamination of the nasal passages.

Topical Medication – Mucous Membranes – Ophthalmic, Otic and Nasal Administration Procedures

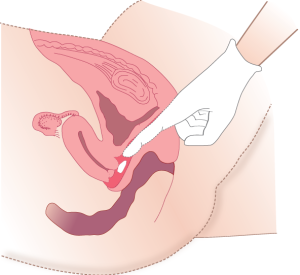

Vaginal Administration

Vaginal medications are used primarily for local treatment, such as hormone therapy or antifungal infections. These medications are available in various forms, including pessaries, foams, creams, jellies, and tablets. Pessaries are solid, oval-shaped preparations that melt at body temperature after insertion, allowing the medication to be absorbed by the vaginal mucosa. They are generally individually packaged and may require refrigeration to maintain their shape. Creams, foams, and jellies are administered using an applicator to ensure the medication is inserted high into the vaginal canal for maximum contact with the mucosal surface. Proper technique is essential to ensure even distribution and effectiveness of the treatment.

Vaginal Medication Administration Procedure

Rectal Administration

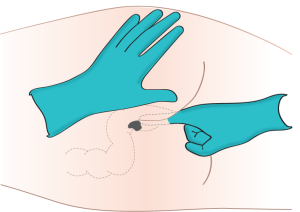

Rectal medications include suppositories and enemas, which may be used for both local and systemic effects. Suppositories are bullet-shaped and designed to melt at body temperature after insertion into the rectum. They are commonly used to relieve constipation, reduce fever, or manage nausea when oral administration is not possible. Suppositories often require refrigeration to maintain their form. Enemas are liquid preparations administered into the rectum, typically in disposable containers, and are used to relieve constipation or deliver medications such as corticosteroids. Rectal administration offers faster absorption and higher bioavailability than oral routes, as it bypasses the upper gastrointestinal tract and reduces gastrointestinal side effects.

Rectal Medication Administration Procedure

Inhalation Administration

Inhaled medications are delivered through the nasal or oral passages, or less commonly via endotracheal tubes, and are rapidly absorbed due to the large surface area and rich vascular supply of the pulmonary tissue. These medications are administered using devices such as nebulisers, metered-dose inhalers (MDIs), dry powder inhalers (DPIs) and soft-mist inhalers. Inhalation therapy is commonly used for respiratory conditions such as asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and allergic rhinitis. Medications delivered via inhalation may have local effects on the airways or systemic effects, such as with general anaesthetics or oxygen therapy. Proper technique is essential to ensure the medication reaches the alveoli, where absorption is most efficient.

Forms of Inhaled Medications

Inhaled medications may be administered by nebulisers or hand atomisers.

Nebuliser

A nebuliser is a process where oxygen or compressed air is used to convert medication to a fine mist for inhalation. The mist is inhaled into the lungs via a face mask or mouthpiece. Nebulisers are usually powered by a compressed air generator, or in the hospital setting, wall compressed air or oxygen may be used.

Inhaled Medication – Nebuliser – Medication Administration Procedure

Hand Atomiser

Hand atomisers (inhalers) are pocket-sized devices that deliver medications into the lungs with each activation. There are three main types of hand atomisers: metered-dose inhalers (MDI), dry powdered inhalers (DPI), and soft-mist inhalers (SMI).

Metered-Dose Inhaler (MDI)

A metered-dose inhaler (MDI), often referred to as a puffer, creates an aerosolised mist of medication that is inhaled through the mouth and into the lungs (Figure 12). The canister is attached to a mouthpiece, and the medication is administered into the lungs by pressing on the canister while coordinating breathing efforts. Hand-breath coordination is required to accurately administer the required dosage to the lungs and prevent wastage occurring in the oropharynx. According to the National Asthma Council Australia (2018), 10% of patients incorrectly administer inhaler medication, therefore, education is of vital importance.

Spacers

A spacer is a clear, hollow tube that attaches to an MDI, creating a chamber between the inhaler and the patient’s mouth or mask (Figure 13). Spacers are particularly useful because they reduce the need for precise coordination between inhaler actuation and inhalation, a common difficulty for many patients (Rigby, 2024). By holding the medication in suspension, spacers allow more time for the patient to inhale the dose effectively.

Spacers offer several clinical benefits. They improve medication delivery by reducing oropharyngeal deposition, which helps minimise local side effects such as hoarseness or oral thrush, especially important when using inhaled corticosteroids (Rigby, 2024). They may also enhance lung deposition by slowing the aerosol cloud and allowing more time for the medication to be inhaled. Spacers are recommended for a wide range of patients, including all children (with a mask for those under 4–5 years), adults using corticosteroid preventers, individuals who struggle with the ‘press and breathe’ technique, and anyone using a reliever during an asthma attack (National Asthma Council [NAC], 2022).

Spacers are available in various sizes and designs, with options for mouthpieces or masks, and may include features such as valves or feedback mechanisms to support correct use (Viken & Levy, 2018).

Dry Powder Inhalers (DPI)

A dry powder inhaler (DPI) provides dry powder medications that are inhaled through a device in the mouth and into the lungs (Figure 12). DPIs use an inward breath to move the medications into the lungs instead of a propellant. After the dose is activated, a quick inhale activates the medication and moves it into the lungs. Typically, DPIs are easy to use, do not require a spacer, and do not require the same coordinated efforts in breathing and operating the device as MDIs. DPIs do, however, require more forceful breaths and therefore, those with a lower forced expired volume (FEV1) may not be able to inspire the medication as adequately (Mondor, 2023). DPIs can also be affected by humidity, so careful storage is required.

Soft-Mist Inhaler

A soft-mist inhaler is a handheld device that turns liquid medications into a mist cloud that can then be inhaled without a propellant (Figure 12). The medication contains more particles and leaves the inhaler more slowly than with MDIs or DPIs; therefore, more of the medication enters the lungs and a lower dose of the medication may be used. This type of inhaler does not require coordinated breathing efforts or a spacer.

Inhaled Medications – Hand Atomisers, MDI, DPI, SMI -Administration Procedure

Life Span Considerations

|

|

Administering Inhaled Medication to Children When administering inhaled medications to children, it is important to choose a device that suits their age, developmental stage, and physical ability (National Asthma Council Australia [NACA], 2018). For children under five, MDIs used with spacers are recommended. Spacers allow the medication to remain suspended, enabling the child to take multiple breaths to inhale the full dose, while also reducing medication build-up in the mouth and minimising local side effects (Viken & Levy, 2018). For younger children, spacers with facemasks are often used to ensure a proper seal. Correct inhaler technique can be challenging for young children. To support learning and reduce anxiety, caregivers can demonstrate the process using a doll or toy and allow the child to explore the equipment beforehand. Having the child sit on a parent’s lap during administration can also help them feel more secure.

|

Key Takeaways

In this chapter, we covered:

- Nurses are responsible for ensuring safe and effective medication administration, which includes assessing the patient, understanding the medication, and evaluating outcomes post-administration.

- Medications can be administered via enteral, topical, or inhaled routes. The choice of route depends on the medication’s properties, therapeutic goals, and the patient’s condition.

- Enteral administration includes oral, sublingual, buccal, and gastric tube routes. Each has specific considerations, such as the impact of first-pass metabolism and the suitability of medication formulations for crushing or tube delivery.

- Topical medications are applied to the skin or mucous membranes and may have local or systemic effects. These include creams, ointments, patches, and preparations for the eyes, ears, nose, rectum, and vagina.

- Inhaled medications are delivered directly to the respiratory tract using devices such as metered-dose inhalers (MDIs), dry powder inhalers (DPIs), soft-mist inhalers, and nebulisers. Proper technique and device selection are essential for effective delivery.

- Nurses must be familiar with different medication formulations (e.g., tablets, syrups, patches) and understand how to administer each safely, including the use of tools like spacers and oral syringes.

- Patient education is a critical component of medication administration. Nurses must teach patients how to use medications correctly and adapt techniques to suit individual needs, especially in vulnerable populations like children or those with swallowing difficulties.

References

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. (2024). Recommendations for safe use of medicines terminology. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/sites/default/files/2024-12/recommendations-for-safe-use-of-medicines-terminology.pdf

Bullock, S., & Manias, B. (2022). Fundamentals of pharmacology (9th ed.). Pearson Education Australia.

Durand, C., Alhammad, A., & Willett, K. C. (2012). Practical considerations for optimal transdermal drug delivery. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy, 69(2), 116–124. https://doi.org/10.2146/AJHP110158

Frotjold, A., & Bloomfield, J. (2021). Ensuring medication safety. In J. Crisp, C. Douglas, G. Reberio, & D. Waters (Eds). Potter & Perry’s fundamentals of nursing (6th ed., Australian & New Zealand ed., pp. 547-637). Elsevier Australia.

Khan S., Sharman T. (2024). Transdermal Medications. In W. B. Ackley, T. S. Adolphe, T. C. Aeby, N. R. Aeddula, S. Agadi, P. Agasthi, S. Ahmad, A. Ahmed, F. W. Ahmed, I. Ahmed, R. A. Ahmed, S. W. Ahmed, A. M. Akanmode, R. Akella, S. M. Akram, Y. Al Khalili, E. Al Zaabi, M. H. Alahmadi, G. Alexander, … H. Zulfiqar (Eds). StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved June 10, 2025 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK556035/

Kim, J., & De Jesus, O. (2023, February 12). Medication routes of administration. In W. B. Ackley, T. S. Adolphe, T. C. Aeby, N. R. Aeddula, S. Agadi, P. Agasthi, S. Ahmad, A. Ahmed, F. W. Ahmed, I. Ahmed, R. A. Ahmed, S. W. Ahmed, A. M. Akanmode, R. Akella, S. M. Akram, Y. Al Khalili, E. Al Zaabi, M. H. Alahmadi, G. Alexander, … H. Zulfiqar (Eds). StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved June 10, 2025 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK568677

Mondor, E. E. (Writer), & Williams, E. (Adaptor). (2023). Nursing management: Obstructive pulmonary diseases. In D. Brown, T. Buckley, R. Aitken, & H. Edwards (Eds). Lewis’s medical-surgical nursing: Assessment and management of clinical problems (6th ed., Australian and New Zealand ed., pp 659-679). Elsevier.

National Asthma Council. (2022). The Australian Asthma Handbook (Version 2.2). https://www.asthmahandbook.org.au/

National Asthma Council Australia. (2018). Inhaler technique for people with asthma or COPD. https://www.nationalasthma.org.au/living-with-asthma/resources/health-professionals/information-paper/hp-inhaler-technique-for-people-with-asthma-or-copd

Rigby D. (2024). Inhaler device selection for people with asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Australian Prescriber 2024(47), 140-147. https://doi.org/10.18773/austprescr.2024.046

Rolf, F. (2021). Medications. In A. Berman, G. Frandsen, S. Snyder, T. Levett-Jones, A. Burston, T. Dwyer, M. Hales, N. Harvey, T. Langtree, L. Moxham, K. Reid-Searl, F. Rolf, D. Stanley, B. Kozier, & G. Erb, (2021). Kozier and Erb’s fundamentals of nursing: Concepts, process and practice (5th Australian ed., Vol 2, pp. 840-915). Pearson Australia.

Vincken, W., Levy, M. L., Scullion, J., Usmani, O. S., Dekhuijzen, P. N. R., Corrigan, C. J. (2018). Spacer devices for inhaled therapy: Why use them, and how? ERJ Open Research 4(2). https://doi.org/10.1183/23120541.00065-2018

Chapter Attribution

This chapter has been adapted in parts from:

Nursing skills 2e (2023) by Open Resources for Nursing, Chippewa Valley Technical College, is used under a CC BY licence.

Clinical nursing skills (2024) by Christie Bowen, OpenStax, is used under a CC BY licence.

Media Attributions

- Oral, buccal and sublingual routes © Eileen Siddins is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Solid medications © a: Victor byckttor b: Thomas Wilson Pratt Slatin is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Liquid measuring devices © Rice University and Open Stax adapted by Leisa Sanderson is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Oral and enteral syringe © Leisa Sanderson (using Copilot) is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Transdermal patch © DanielTahar is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Transdermal patch © Glynda Rees Doyle & Jodie Anita McCutcheon is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Eye Drops © George Coogan is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Administering medication vaginally without an applicator © Glynda Rees Doyle & Jodie Anita McCutcheon is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Administering medication vaginally using an applicator © Glynda Rees Doyle & Jodie Anita McCutcheon is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Administration of enema © Glynda Rees Doyle & Jodie Anita McCutcheon is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Nurse administering Nebuliser © George Coogan is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Metred dose inhaler, dry powder inhaler and soft mist inhaler © Eileen Siddins is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Patient using MDI with spacer © George Coogan is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license