Pain Assessment and Management

Amy McCrystal and Jessica Best

Learning Outcomes

In this chapter you will learn how to:

- Describe the four processes involved in nociception and how pain interventions can work during each process

- Differentiate types of pain

- Understand factors that may impact pain (eg/ lifespan, sociocultural, gender considerations, stressors, etc.)

- Accurately assess pain and utilise appropriate assessment methods.

Pain is a complex and subjective experience that varies greatly among individuals, making its assessment and management a critical component of nursing practice. Margo McCaffery, a highly recognised nurse and pioneer pain educator, defined pain as “… whatever the experiencing person says it is, existing whenever he/she says it does.” In other words, pain is personal. You, the person experiencing it, define it and translate it (McCaffery, 1968). This chapter provides an overview of the physiological and psychological aspects of pain, explores evidence-based approaches to pain assessment, and discusses strategies for effective pain management. By understanding the principles of pain management, nurses can deliver compassionate, patient-centred care that alleviates suffering and enhances quality of life.

Pain Classifications

Pain can be classified in many ways. Several classifications are presented below. It is important to recognise that these are not mutually exclusive, and a person may experience multiple classifications of pain at the same time.

Concepts Related to Pain

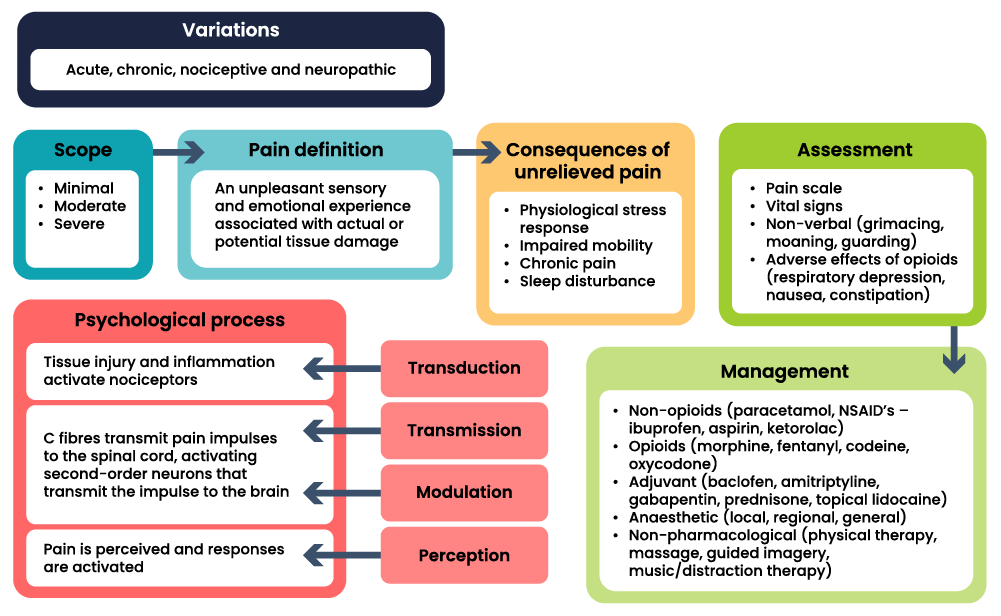

This section provides a basic introduction to the concept of pain as it relates to pharmacology. The concept of pain is defined as “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage”. The concept map below provides a summary of the key information necessary to understand pain informed by several resources.

Physiology of Pain

Before addressing the medications used to manage pain, it is essential to understand the physiology of pain. Pain is a complex experience that arises when tissue damage occurs within the body. This tissue damage activates pain receptors located in peripheral nerves, known as nociceptors. These specialised nerve endings are distributed throughout various tissues, including arterial walls, joint surfaces, muscle fascia, periosteum, skin, and soft tissue; however, they are relatively sparse in most internal organs.

Tissue damage can result from a variety of causes, which can be classified as either physical or chemical. Physical factors include heat, cold, pressure, stretching, spasms, and ischaemia, while chemical factors involve the release of pain-producing substances into the extracellular fluid surrounding the nerve fibres that transmit pain signals. These substances not only activate pain receptors but also heighten their sensitivity and stimulate the release of inflammatory mediators such as prostaglandins. Additionally, pain can trigger the physiological stress response.

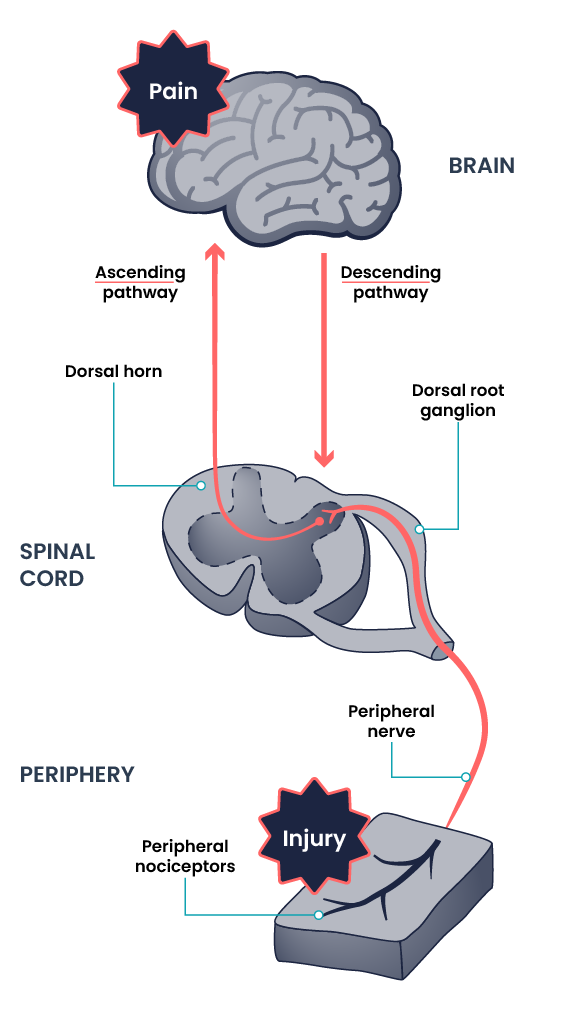

For an individual to experience pain, the signal generated by nociceptors in peripheral tissues must be effectively transmitted to the spinal cord and subsequently to the hypothalamus and cerebral cortex of the brain. This transmission is facilitated by two primary types of nerve fibres: A-delta fibres, which are responsible for sharp, immediate pain, and C fibres, which convey dull, persistent pain. The dorsal horn of the spinal cord serves as a relay station for information from these nerve fibres.

Within the brain, the thalamus acts as a critical relay station for incoming sensory stimuli, including pain. Once the signals reach the thalamus, they are transmitted to the cerebral cortex, where they are consciously perceived. This process involves four key stages of nociception:

- Transduction: This initial stage occurs when nociceptors are activated by a noxious stimulus such as heat, pressure, or chemical irritation. The painful stimuli are converted to electrical impulses (action potential) that signify the possibility of actual or potential tissue damage (Lee & Neumeister, 2020).

- Transmission: The electrical signals generated during transduction are transmitted along the A-delta and C fibres to the spinal cord. Here, the signals are relayed to the brain via the dorsal horn (Lee & Neumeister, 2020).

- Perception: This stage occurs in the cerebral cortex, where the brain interprets and consciously perceives the pain. This stage is influenced by a range of factors, including emotional and psychological components (Lee & Neumeister, 2020).

- Modulation: Throughout this pathway, pain transmission can be modified via various factors. Inhibitory interneurons in the spinal cord can dampen pain signals, and the brain can also send descending signals that modulate the perception of pain through neurotransmitters like serotonin and norepinephrine (Lee & Neumeister, 2020). These neurotransmitters can either amplify or inhibit the pain signals, influencing the overall perception of pain.

The four processes of nociception; transduction, transmission, perception and modulation are demonstrated in Figure 2 below.

Pain Assessment Methods

Effective pain assessment is essential for understanding a patient’s experience and guiding appropriate management strategies. Nurses use a variety of methods to evaluate pain, including self-reports, observational tools, and physical assessments. These methods help identify the type, intensity, and impact of pain on a patient’s daily life. A thorough assessment ensures that pain management interventions are tailored to the individual’s needs, promoting better outcomes and improved quality of care.

Subjective Pain Assessment Methods

The numeric rating scale (NRS) is a pain screening tool commonly used to assess pain severity at that moment in time. The nurse will ask a patient to rate the severity of their pain on a scale from 0 to 10, with “0” being no pain and “10” being the worst pain imaginable is a common question used to screen patients for pain. This question can be used to initially screen a patient for pain, but a thorough pain assessment is required. Additionally, the patient’s comfort-function goal must be assessed and documented. This individualised comfort-function goal provides the basis for the patient’s pain treatment plan and is used to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions and make changes as needed.

OPQRSTUV

The OPQRSTUV mnemonic is a systematic approach used to collect key information required for a comprehensive pain assessment. The framework guides the nurse through the key aspects of a pain evaluation by considering the following:

- Onset: When was the beginning of the pain?

- Provocative/palliative factors: Factors that bring the pain on, or make it worse and factors that reduce or alleviate the pain.

- Quality/quantity: Characteristics and nature of the pain.

- Region/radiation: Location and spread of pain.

- Severity: Intensity level of the pain.

- Timing: Duration of the pain.

- Understanding: Patient’s interpretation of the pain.

- Values: Impact on pain on the person’s values.

When assessing the person, nurses should apply a holistic approach and use open-ended questions from this framework to gather detailed information, if responses seem inconsistent, they then employ follow-up questions to validate the data. For example, if a patient states that “the pain is tolerable” but rates the pain as a “7” on a 0 to 10 pain scale, further questioning may reveal the pain varies with activity, such as being higher during physiotherapy but is manageable during rest. This additional information allows the nurse to customise pain management strategies to the patient’s needs and therefore provide more effective interventions. Sample questions when using the OPQRSTUV assessment are included below.

FACES Scale

The FACES scale is a visual tool for assessing pain in children and others who cannot quantify the severity of their pain on a scale of 0 to 10. See Figure 4 for the FACES Pain Rating Scale. To use this scale, use the following evidence-based instructions. Explain to the patient that each face represents a person who has no pain (hurt), some pain, or a lot of pain. “Face 0 doesn’t hurt at all. Face 2 hurts just a little. Face 4 hurts a little more. Face 6 hurts even more. Face 8 hurts a whole lot. Face 10 hurts as much as you can imagine, although you don’t have to be crying to have this worst pain.” Ask the person to choose the face that best represents the pain they are feeling. Note that the person reports which face best represents how they are feeling, and the nurse does not select a face based on how the person appears to feel.

FLACC Scale

The FLACC scale (i.e., the Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, Consolability scale) is a measurement used to assess pain for children between the ages of two months and seven years or individuals who are unable to verbally communicate their pain. The scale has five criteria, which are each assigned a score of 0, 1, or 2. The scale is scored in a range of 0 to 10 with “0” representing no pain. See Table 2 for the FLACC scale. Like all behavioural tools, the FLACC cannot distinguish between pain and other forms of distress. Think critically when interpreting behaviours that may be pain-related and when making treatment decisions based on the FLACC total score. You should observe the patient for at least two to five minutes before assigning a score.

|

Criteria |

Score 0 |

Score 1 |

Score 2 |

|

Face |

No particular expression or smile |

Occasional grimace or frown, withdrawn, or uninterested |

Frequent to constant quivering chin; clenched jaw |

|

Legs |

Normal position or relaxed |

Uneasy, restless, or tense |

Kicking or legs drawn up |

|

Activity |

Lying quietly, normal position, and moves easily |

Squirming, shifting, back and forth, or tense |

Arched, rigid, or jerking |

|

Cry |

No cry (awake or asleep) |

Moans or whimpers or occasional complaint |

Crying steadily, screams or sobs, or frequent complaints |

|

Consolability |

Content and relaxed |

Reassured by occasional touching, hugging, or being talked to; distractible |

Difficult to console or comfort |

Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia (PAINAD) Scale

The Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia (PAINAD) Scale is a simple, valid, and reliable instrument for assessing pain in noncommunicative patients with advanced dementia. See Table 3 for the items included on the scale. Each item is scored from 0 to 2, and when totalled, the score can range from 0 (no pain) to 10 (severe pain).

|

Item |

0 |

1 |

2 |

|

Breathing independent of vocalisation |

Normal |

Occasional laboured breathing. Short period of hyperventilation. |

Noisy laboured breathing. Long period of hyperventilation. Cheyne-Stokes respirations. |

|

Negative vocalisation |

None |

Occasional moan or groan. Low-level speech with a negative or disapproving quality. |

Repeated troubled calling out. Loud moaning or groaning. Crying. |

|

Facial Expression |

Smiling or inexpressive |

Sad. Frightened. Frown. |

Facial grimacing. |

|

Body language |

Relaxed |

Tense. Distressed pacing. Fidgeting. |

Rigid. Fists clenched. Knees pulled up. Pulling or pushing away. Striking out. |

|

Consolability |

No need to console |

Distracted or reassured by voice or touch. |

Unable to console, distract, or reassure. |

Download the full PAINAD scale from The Hartford Institute for Geriatric Nursing.

Pain Assessment in Patients with Impaired Cognition (PAIC15)

The PAIC15 Scale is a recently developed tool for use with individuals who are cognitively impaired, particularly those with dementia. It was developed through a large multidisciplinary collaboration of clinical, research, and methodological experts, including nurses, from several European countries. The team of experts developed this new meta-tool over a period of seven years, during which team members empirically evaluated items from all existing pain-related observational tools and reached a consensus on the 15 most promising items, based on validity and reliability.

As shown in the tool, the PAIC15 includes 15 descriptors with five items each for:

- Facial expression

- Body movements

- Vocalisation.

The PAIC15 is helpful when you have limited time with the patient, as you can quickly assess pain either at rest or with movement. Download the full PAIC15 scale.

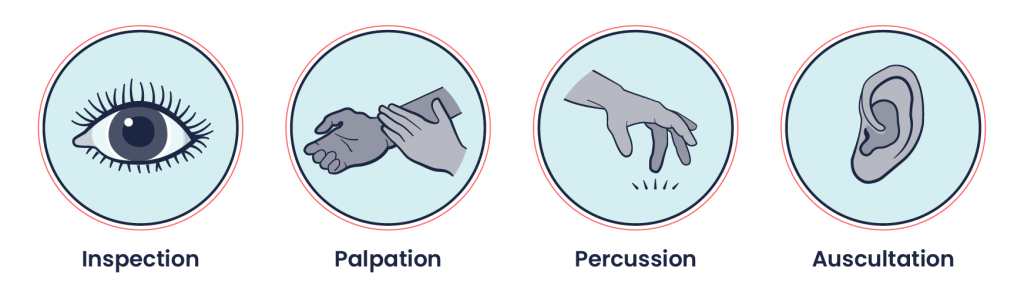

Objective Pain Assessment Methods

It is always important to perform an objective assessment following a subjective assessment, but this is particularly the case for infants, young children, and non-verbal patients who may have difficulties with self-reporting.

The type of objective assessment used will depend on the location of the pain, the related body systems, and the acuity of the situation. Focused assessments of the body system may be necessary. For example, if a person describes knee pain, you should do a focused assessment of the musculoskeletal system. If a patient describes chest pain, you should do a focused assessment of the cardiovascular system, the respiratory system, and possibly the musculoskeletal system.

The objective assessment does not follow a specific order; it depends on the acuity of the situation and the stability of the patient. Common components of an objective assessment of pain include the following.

Full Set of Vital Signs

Vital signs can be affected by pain, particularly acute pain. Collection and assessment of vital sign data may provide important information related to the patient’s stability and the potential for clinical deterioration. Vital signs are also an important component of pain tools that include physiological measures; these can be particularly helpful in patients who are pre-verbal or non-verbal such as newborns, young children, patients that may have a developmental challenge, and unconscious patients. However, vital sign changes cannot help you differentiate between pain and other forms of distress such as fear and anxiety. You should always consider the context when interpreting vital signs because they can be affected by the level of consciousness, medications, and sedation. Therefore, your clinical judgement will be based on a comprehensive subjective and objective assessment, along with critical thinking.

|

Inspection of the area: Typically, you will inspect the area on the body where a patient indicates they are having pain. Inspection is performed bilaterally in which you compare the left side to the right side. For example, if a patient is having eye pain, you should compare the left eye to the right eye. Inspect for and note any abnormalities such as discolouration (e.g., redness), bruising, swelling, scarring, incisions, masses, deformities, asymmetry, lesions, non-intact skin, and pressure injuries. |

|

Palpation of the area: After conducting a subjective assessment, you should palpate the area (and related areas) in which the patient is having pain. Palpation is performed bilaterally: compare the left side to the right side. For example, if a patient is having left shoulder pain, you should palpate the right shoulder first and then the painful left shoulder. You should also observe any signs of pain during palpation, such as a change in respiration (e.g., holding their breath), facial grimacing, withdrawing their body/limb, and guarding. |

|

Perform auscultation and percussion when a patient is describing chest or abdominal pain. For example, with chest pain, you should auscultate the lungs and the apical pulse and cardiac valves. |

Priorities of Care

Some of the main priorities of care related to pain assessment include:

Spiritual, Mental and Behavioural (including Gendered) Considerations of Pain

When we first see a patient, we tend to make assumptions about the presence and even the severity of pain based on readily available cues (e.g., facial expression, body positioning, vocalisations). These assumptions are rooted in our biases regarding what pain looks and even sounds like. These biases may emerge from our own experiences. Our initial impressions of a patient’s pain can form what is called an “anchor” or have an “anchor effect” in which all additional assessments of the patient’s pain are influenced by these initial impressions (Rivi et al., 2011). These assumptions can also be based on ageist ideas, for example, that older people or newborns do not feel pain. Another biased assumption is that people living with cognitive impairment (such as dementia) do not feel pain in the same way as others because they may have difficulty articulating that pain.

Patients with mental health disorders may be seen as behavioural as opposed to being in pain. These assumptions can mean that pain is under-assessed and undertreated in certain populations. It is also very important to be aware that some people may openly talk about their pain and cry out in agony, while others may be stoic and hide their pain. Some people may stay home in bed when they are in pain while others may continue with their daily life and go to work. A patient’s spiritual beliefs may also influence how they communicate their pain.

Gender is a sociocultural construct, related to, but not interchangeable with biological sex, that has significant implications on how individuals experience pain. Studies have shown that sociocultural influences, such as gender roles, expectations, and social learning, contribute to gender differences in the pain experience (Pedulla et al., 2024). According to some studies, Females tend to experience pain more intensely and have lower pain tolerances and thresholds than males (Pedulla et al., 2024). Additionally, differences in pain outcomes between men and women have been attributed to psychological differences such as decreased self-efficacy, differing pain coping strategies, and higher pain-catastrophising levels in women than men. The proposed mechanisms for these sex differences in the experience of pain have been widely researched and are attributed to several biopsychosocial factors. Understanding the gender roles can enhance person-centred interaction and care-plans.

Comfort-Function Goals

Comfort-function goals encourage the patient to establish the level of comfort needed to achieve functional goals based on their current health status. For example, one patient may be comfortable ambulating after surgery and their pain level is 3 on a 0-to-10 pain intensity rating scale. In contrast, another patient desires a pain level of 0 on a 0-to-10 scale to feel comfortable ambulating. To properly establish a patient’s comfort-function goal, nurses must first describe the essential activities of recovery and explain the link between pain control and positive outcomes. If a patient’s pain score exceeds their comfort-function goal, nurses must implement an intervention and follow up within 1 hour to ensure the intervention was successful. Using the previous example, if a patient had established a comfort-function goal of 3 to ambulate and the current pain rating was 6, the nurse would provide appropriate interventions, such as medication, application of cold packs, or relaxation measures. The nurse would then perform a follow-up assessment within an hour to evaluate the effectiveness of these interventions. Documentation of the comfort-function goal, pain level, interventions, and follow-up are key to effective, individualised pain management.

Pain Management Strategies

Pain can be challenging for patients, and understanding how to manage it is crucial. Holistic Nursing is defined as “all nursing practice that has healing the whole person as its goal” (Thornton, 2019). As pain can impact a patient not just physically, but affect mental health, sleep, social life, etc., a holistic approach to nursing care plays a major role in enabling positive outcomes for patients experiencing pain. It is also important to include a patient in their care, for example, in the planning and evaluating of pain management strategies along with setting goals. The following section will look at various pain management strategies that are important to providing effective nursing care. Two main strategies will be explored; this includes pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapies. Effective pain management will often use a combination of these strategies.

Pharmacological Therapy

Pharmacological therapy can be very effective in treating pain. Pharmacological therapy is the use of medication to treat a disease, illness, or medical condition. The type of medication depends on the type, duration, and severity of the pain (Ford, 2019). There are three main types of pain medications: opioid analgesics, non-opioid analgesics, and adjuvants. An analgesic is a medication used to relieve pain. When administering pain medications, the nurse must consider the patient’s goals for pain relief and determine if past medications have been effective. The nurse must also consider if the patient is experiencing any side effects that may impact the patient and be aware of contraindications. Patients should be involved and engaged in their pain management plan. Research has shown improved patient outcomes when patients work together with the healthcare team to manage their pain.

In 1986, the World Health Organisation (WHO) proposed the WHO analgesic ladder to provide adequate pain relief for cancer patients (Aabha et al., 2023). The ladder mainly consists of three steps:

- First Step – Mild pain: non-opioid analgesics such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or acetaminophen with or without adjuvants

- Second Step – Moderate pain: weak opioids (hydrocodone, codeine, tramadol) with or without non-opioid analgesics and with or without adjuvants

- Third Step – Severe and persistent pain: potent opioids (morphine, methadone, fentanyl, oxycodone, buprenorphine, tapentadol, hydromorphone, oxymorphone) with or without non-opioid analgesics, and with or without adjuvants

This analgesic path, developed following the recommendations of an international group of experts, has undergone several modifications over the years and is currently applied for managing cancer pain but also acute and chronic non-cancer painful conditions due to a broader spectrum of diseases such as degenerative disorders, musculoskeletal diseases, neuropathic pain disorders, and other types of chronic pain (Aabha et al., 2023). The fundamental concept of the ladder is that it is essential to have adequate knowledge about pain, to assess its degree in a patient through proper evaluation, and to prescribe and administer appropriate medications.

Opioid Analgesics

An opioid analgesic is a powerful prescription medication that helps reduce pain by blocking pain signals. Common opioids include codeine, morphine, fentanyl, oxycodone, and tramadol. Different opioids have different amounts of analgesia, ranging from codeine used to treat mild to moderate pain, to morphine used to treat severe pain. Opioids are commonly administered orally or intravenously, but can also be administered rectally, subcutaneously, intramuscularly, or through the skin. The following are some common opioid analgesics.

Opioid Risks

Opioids have a high risk of addiction and overdose, so it is important to consider other forms of pain management before prescribing opioids (National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, 2022). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends avoiding opioids for pain management in patients younger than 18 years old, and avoiding opioids as first-line therapy for chronic pain (Dowell et al., 2022). First-line therapy is medical treatment that is recommended as the best option for the initial treatment of a disease or medical condition.

|

It is important that patients are informed about the side effects and risks of opioids. Side effects of opioids include the following:

|

Constipation, nausea, and vomiting are common side effects of opioids. Opioids slow peristalsis and cause increased reabsorption of fluid into the large intestine, resulting in slow-moving, hard stools. Nurses should educate patients on preventing constipation with a bowel management program including stool softeners, fluids, a well-balanced diet, and physical activity (as allowed with pain/postsurgical restrictions) to aid in preventing constipation. Because opioids slow gastrointestinal mobility, nausea and vomiting can also occur when taking opioids. Typically, patients will build enough tolerance against nausea and vomiting after taking opioids for a few days. Respiratory depression is one of the most serious potential side effects of opioids. Nurses must closely monitor patients receiving opioids for respiratory depression and administer naloxone to reverse the opioid effects if needed.

As important as pain management is, it is also crucial that healthcare providers are mindful of prescribing opioids to treat pain due to the high risk of addiction and overdose. Addiction is a chronic disease of the brain pursuing reward and/or relief by substance use. Patients who have an addiction have trouble stopping the use of opioids and often struggle with addiction for the rest of their lives. Patients can also struggle with tolerance and physical dependence on opioid misuse. Tolerance is when the body builds up resistance to a medication. Physical dependence is when the patient experiences physical symptoms of withdrawal, such as anxiety, diaphoresis, and muscle cramps when stopping a medication (National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, 2022). Opioids can be very effective in pain management when used appropriately, but healthcare providers must monitor for serious side effects (ANA Center for Ethics and Human Rights, 2018).

Nursing Considerations for Opioids

The nurse should do the following for patients who are taking an opioid:

- Assess the patient’s pain before and after administering an opioid to determine its efficacy in treating the patient’s pain.

- Watch for adverse effects, including sedation, ataxia (a term for a group of disorders that affect coordination, balance and speech), slurred speech, and shallow breathing, which could require the use of antidotal therapy or respiratory support.

- With chronic use of opioids, ask about the patient’s bowel movements because constipation is very common with these medications and could be a source of abdominal pain.

- Ensure that naloxone is readily available in the event of opioid toxicity or overdose.

- Provide patient teaching regarding the drug and when to call the healthcare provider.

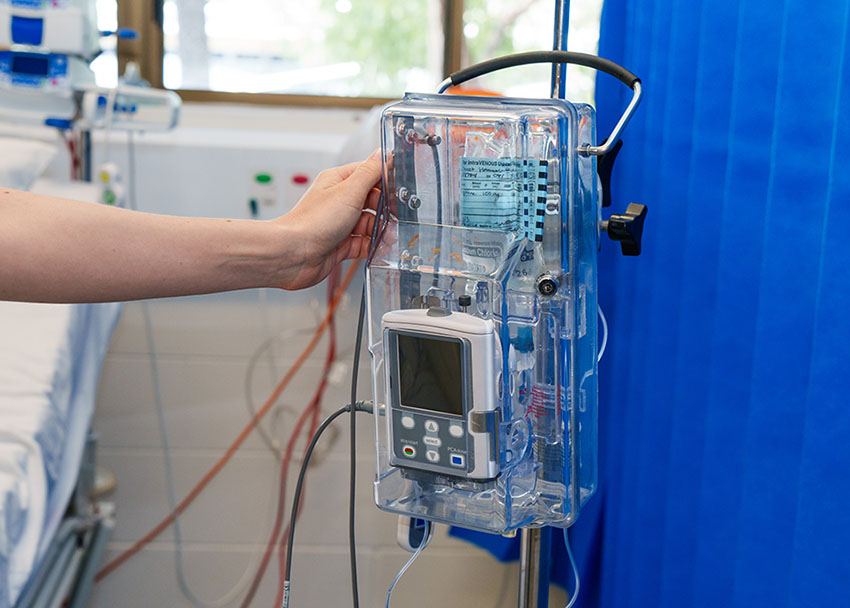

Patient-Controlled Analgesia

Hospitalised patients with severe pain may receive patient-controlled analgesia (PCA), which allows the patients to safely self-administer opioid medications using a programmed pump. PCA is used to treat acute, chronic, labour, and postoperative pain. A computerised pump contains an opioid analgesic that is connected directly to a patient’s intravenous (IV) line. Doses of medication can be self-administered as needed by the patient by pressing a button. However, the pump is programmed to only allow the administration of medication every set number of minutes with a dose of medication every hour. These pump settings, and the design of the system requiring the patient to be alert enough to press the button, are safety measures to prevent overmedication that can cause sedation and respiratory depression. For this reason, no one but the patient should press the button for administration of medication (not even the nurse). In other cases, the PCA pump delivers a small, continuous flow of pain medication intravenously with the patient self-delivering additional medication as needed, according to the limits set on the pump. PCA is useful for patients who have acute pain due to conditions such as trauma, burns, or pancreatitis (Pastino & Lakra, 2023).

The ability of the patient to self-administer pain medication has been shown to increase patient satisfaction and deliver timely pain interventions (Pastino & Lakra, 2023). It also alleviates the burden on both the nurse and the patient of adhering to a strict dosing schedule for PRN analgesics, which may not always provide sufficient pain relief. PCA may be appropriate for patients who are unable to tolerate oral pain medications or for patients who have breakthrough pain and need frequent dosing. The patient can time their medication according to the pain severity for better pain reduction and control.

Nursing Considerations for a PCA

PCA pumps must have certain orders relating to the bolus dose, basal rate, and lockout time. The bolus dose is the dose the patient receives each time they press the button on the PCA pump and is used for breakthrough pain. The basal rate is the continuous rate of the medication that maintains effective pain management. The lockout time is the amount of time after a bolus dose that the pump will not administer medication to the patient, even if they press the button, to prevent overdose. The PCA doses may be dependent on the type of medication, IV site, patient’s weight, current research, and facility guidelines (Pastino & Lakra, 2023). It is important to review your facility’s guidelines when programming PCA dosing.

There are contraindications for PCA. If the patient cannot understand how the PCA works and follow directions, such as understanding how and when to press the button, they would not be good candidates for PCA. Allergies, infection, increased intracranial pressure, disability, chronic kidney failure, and bleeding disorders are also contraindications for PCA (Pastino & Lakra, 2023).

Side effects of PCA use are the same as opioids and include constipation, nausea and vomiting, urinary retention, and pruritus (itching). The most serious potential adverse effect of opioids is respiratory depression. Respiratory depression is usually preceded by sedation. The nurse must carefully monitor patients receiving opioids for oversedation, which results in a decreased respiratory rate. Patients at greatest risk are those who have never received an opioid and are receiving their first dose, those receiving an increased dose of opioids, or those taking benzodiazepines or other sedatives concurrently with opioids. If a patient develops opioid-induced respiratory depression, the opioid is reversed with naloxone (Narcan) which immediately reverses all analgesic effects.

Nurses must follow facility guidelines when administering PCA and ensure that the pump is set up correctly. Many facilities have safeguards in place such as a dual nurse sign-off, scanning medications into the electronic medication administration record (eMAR), and guardrails on the pumps to prevent medication errors. To document the amount and frequency of pain medication the patient is receiving, as well as to prevent drug diversion, the settings on the pump are checked at the end of every shift by the nurse as part of the bedside report. The incoming and outgoing nurses double-check and document the pump settings, the amount of medication administered during the previous shift, and the amount of medication left in the syringe.

Non-Opioid Analgesics

A non-opioid analgesic refers to any pharmacologic agent that treats the symptoms of pain and does not involve the activation of opioid receptors. These agents generally work by inhibiting cyclooxygenase (COX), a major pro-inflammatory enzyme that causes many signs and symptoms of inflammation, including redness, swelling, and sensitisation of nociceptors, thereby increasing the transmission of painful signals to the brain. COX causes this increase in inflammation and pain by increasing the production of cytokines such as prostaglandins, prostacyclin, and thromboxane. It is also partly responsible for the pyrexia that occurs with infection, which is why many non-opioid analgesics that block the activity of COX also work as antipyretics to reduce fever.

Cyclooxygenase has two major isoforms: COX-1 and COX-2. COX-1 helps with normal homeostatic functions in the body, including maintaining normal platelet and renal functions. It also is important for producing prostaglandins that stimulate production of the mucosal barrier that protects the stomach from its acids. If COX-1 is inhibited through the actions of medications such as glucocorticoids or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), this protective barrier can erode, which is a major cause of peptic ulcers. COX-2 is responsible for much of the inflammation and pain brought about by tissue injury. Other non-opioid analgesics may serve as adjunctive agents for treating neuropathic sources of pain. These include antidepressant drugs (e.g., duloxetine, amitriptyline), antiseizure drugs (e.g., carbamazepine, pregabalin), and local anaesthetics (e.g., lidocaine and bupivacaine). These are useful because they target the abnormal neuronal function that is the source of neuropathic pain.

Adjuvant Analgesics

An adjuvant analgesic is a type of medication that is not classified as an analgesic but has been found to have an analgesic effect along with opioids. Adjuvant medications include antidepressants and anticonvulsants such as gabapentin and amitriptyline. Adjuvant analgesics can be very effective for neuropathic pain but may not be as effective for somatic or visceral pain (Jacques, 2022). Antidepressants can help control how pain signals are delivered to and processed by the brain. Amitriptyline is a tricyclic antidepressant that can help treat neuropathic pain. Amitriptyline can cause sedative effects, so it is usually administered at bedtime. Anticonvulsants can block certain types of pain signals and help decrease neuropathic pain (Jacques, 2022). Gabapentin is an anticonvulsant that can also treat neuropathic pain and restless leg syndrome. Side effects of gabapentin include mental health changes, drowsiness, and weakness. Other medications such as corticosteroids, muscle relaxants, and topical agents can also help reduce pain. Corticosteroids decrease inflammation and topical agents can be directly applied to the skin to decrease pain (Jacques, 2022). Adjuvant analgesics can help reduce pain in a variety of ways but are not always effective on their own.

Non-Pharmacological Therapy

A type of therapy called non-pharmacological therapy can be very effective when used in conjunction with pharmacological therapy. Non-pharmacological therapy is any intervention that helps reduce pain without using medication. Non-pharmacological therapy can include psychological, emotional, and environmental therapies. Psychological and emotional therapies can be incorporated into the daily lives of patients and can be especially useful in treating chronic pain. Psychological and emotional therapy can include relaxation techniques, music, breathing, art therapy, distraction, meditation, or cognitive behavioural therapy. Changing the environment can also help patients manage their pain. Adjusting lighting, sounds, and temperature to a more relaxing environment has been shown to reduce pain (Ford, 2019). Exercise and physical therapy can also help reduce pain without the side effects of pharmacological therapy. Patients can easily incorporate non-pharmacological therapy such as physical therapy into their daily lives without risks.

Key Takeaways

In this chapter, we covered:

- How pain can be classified in many ways including acute pain, chronic pain, nociceptive pain, neuropathic pain, nociplastic pain, idiopathic pain and referred pain

- How nurses can use a variety of assessment methods to evaluate pain. These include subjective pain assessment methods such as 0-10 rating, OPQRSTUV, FACES scale, FLACC scale, PAINAD scale and the PAIC15 scale. Objective pain assessment methods such as inspection, palpation, percussion and auscultation as well as vital signs

- Priorities of care related to pain assessment include chest pain, a significant increase in pain, inadequately managed postoperative pain, pain unrelieved by opioid analgesia in limb injury and back pain

- The physiology of pain and the four key stages of nociception: transduction, transmission, perception, and modulation

- Pain management strategies such as pharmacological therapy. This includes opioid analgesics and the risks around these medications; patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) and nursing considerations; non-opioid analgesics and adjuvant analgesics.

- How non-pharmacological therapy can be effective when used in conjunction with pharmacological therapy. Some examples are: cold and heat, physical therapy, massage, guided imagery and distraction.

References

Anekar, A. A., Joseph Maxwell Hendrix, J. M., Cascella, M. (2023). WHO Analgesic Ladder. In W. B. Ackley, T. S. Adolphe, T. C. Aeby, N. R. Aeddula, S. Agadi, P. Agasthi, S. Ahmad, A. Ahmed, F. W. Ahmed, I. Ahmed, R. A. Ahmed, S. W. Ahmed, A. M. Akanmode, R. Akella, S. M. Akram, Y. Al Khalili, E. Al Zaabi, M. H. Alahmadi, G. Alexander, … H. Zulfiqar (Eds). StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved March 13, 2025 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554435/

Bonezzi, C., Fornasari, D., Cricelli, C., Magni, A., & Ventriglia, G. (2020). Not all pain is created equal: Basic definitions and diagnostic work-up. Pain and Therapy, 9(Suppl. 1), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40122-020-00217-w

Chu, B., Marwaha, K., Sanvictores, T., Awosika, A. O, Ayers, D. (2024). Physiology, stress reaction. In W. B. Ackley, T. S. Adolphe, T. C. Aeby, N. R. Aeddula, S. Agadi, P. Agasthi, S. Ahmad, A. Ahmed, F. W. Ahmed, I. Ahmed, R. A. Ahmed, S. W. Ahmed, A. M. Akanmode, R. Akella, S. M. Akram, Y. Al Khalili, E. Al Zaabi, M. H. Alahmadi, G. Alexander, … H. Zulfiqar (Eds). StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved March 12, 2025 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK541120/

Dowell, D., Ragan, K. R., Jones, C. M., Baldwin, G. T., Chou, R. (2022). CDC clinical practice guideline for prescribing opioids for pain – United States 2022. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 71(3), 1–95. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/71/rr/pdfs/rr7103a1-h.pdf

Fitzcharles, M., Cohen, S., Clauw, D., Littlejohn, G., Usui, C., & Häuser, W. (2021). Nociplastic pain: Towards an understanding of prevalent pain conditions. The Lancet, 397(10289), 2098-2110. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00392-5

Ford. C. (2019). Adult pain assessment and management. British Journal of Nursing, 28(7). https://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/id/eprint/39125/1/Ford%20-%20Adult%20pain%20assessment%20and%20management%20AAM.pdf

Ibitoye, B. M., Oyewale, T. M., Olubiyi, K. S., Onasoga, O. A. (2019). The use of distraction as a pain management technique among nurses in a north-central city in Nigeria. International Journal of Africa Nursing Sciences, 11. Article 100158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijans.2019.100158

International Association for the Study of Pain. (2021). Terminology. https://www.iasp-pain.org/resources/terminology/#pain

Jacques, E. (2022). How adjuvant analgesics are used to treat chronic pain. Verywell Health. https://www.verywellhealth.com/what-are-adjuvant-analgesics-2564529

Kosek, E., Cohen, M., Baron, R., Gebhart, G., Mico, J., Rice, A., Rief, W., & Sluka, K. (2016). Do we need a third mechanistic descriptor for chronic pain states? Pain: The Journal of the International Association for the Study of Pain, 157(7), 1382-1386. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000507

Lee, G. I., & Neumeister, M. W. (2020). Pain: Pathways and physiology. Clinics in Plastic Surgery, 47(2), 173–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cps.2019.11.001

McCaffery M. (1968). Nursing practice theories related to cognition, bodily pain, and man-environment interactions. UCLA Students Store.

Nall, R. (2021). Pain relief basics. Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health/pain-relief#exercise

National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. (2022). Opioid therapy and different types of pain. Centers for Disease Control. and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/overdose-prevention/manage-treat-pain/

National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2023, July 10). Drug overdose death rates. National Institutes of Health. https://nida.nih.gov/research-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates#Fig4

Parker, C., & Kaim, K. (2021). Optimising skin integrity and wound care. In Crisp, J., Douglas, C., Rebeiro, G., Waters, D. Potter & Perry’s Fundamentals of Nursing Australia and New Zealand 6th edition. Elsevier.

Pastino, A. & Lakra, A. (2023). Patient-controlled analgesia. In W. B. Ackley, T. S. Adolphe, T. C. Aeby, N. R. Aeddula, S. Agadi, P. Agasthi, S. Ahmad, A. Ahmed, F. W. Ahmed, I. Ahmed, R. A. Ahmed, S. W. Ahmed, A. M. Akanmode, R. Akella, S. M. Akram, Y. Al Khalili, E. Al Zaabi, M. H. Alahmadi, G. Alexander, … H. Zulfiqar (Eds). StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved January 8, 2025 from www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK551610/

Pedulla, R., Glugosh, J., Jeyaseelan, N., Prevost, B., Velez, E., Winnitoy, B., Churchill, L., Raghava Neelapala, Y. V., & Carlesso, L. C. (2024). Associations of gender role and pain in musculoskeletal disorders: A mixed-methods systematic review. The Journal of Pain, 25(12), Article 104644. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2024.104644

Riva, P., Rusconi, P., & Montali, L. (2011). The influence of anchoring on pain judgment. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 42(2), 265-277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.10.264

Thornton L. (2019). A brief history and overview of holistic nursing. Integrative Medicine, 18(4), 32–33. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7219452/

Torlincasi, A.M., Lopez, R. A., Waseem, M. (2023). Acute Compartment Syndrome. In W. B. Ackley, T. S. Adolphe, T. C. Aeby, N. R. Aeddula, S. Agadi, P. Agasthi, S. Ahmad, A. Ahmed, F. W. Ahmed, I. Ahmed, R. A. Ahmed, S. W. Ahmed, A. M. Akanmode, R. Akella, S. M. Akram, Y. Al Khalili, E. Al Zaabi, M. H. Alahmadi, G. Alexander, … H. Zulfiqar (Eds). StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved February 3, 2025 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448124/

Treede, R., Rief, W., Barke, A., Azia, Q., Bennett, M., Benoliel, R., Cohen, M., Evers, S., Finnerup, N., First, M., Giamberardino, M., Kaasa, S., Korwisi, B., Kosek, E., Lavand’homme, P., Nicholas, M., Perrot, S., Scholz, J., Schug, S., Smith, B., Svensson, P., Vlaeyen, J., & Wang, S. (2019). Chronic pain as a symptom or a disease: The IASP Classification of Chronic Pain for the International Classification of Disease (IDC-11). Pain: The Journal of the International Association for the Study of Pain, 160(1), 19-27. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001384

Trottier, E. D., Doré-Bergeron, M. J., Chauvin-Kimoff, L., Baerg, K., & Ali, S. (2019). Managing pain and distress in children undergoing brief diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. Paediatrics & Child Health, 24(8), 509–535. https://doi.org/10.1093/pch/pxz026

West, M. (2022). What to know about guided imagery. Medical News Today. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/guided-imagery

Chapter Attributions

This chapter has been adapted in parts from:

Fundamentals of nursing (2024) edited by Christy Bowen, Lindsay Draper and Heather Moore, OpenStax, is used under a CC BY licence.

Fundamentals of nursing pharmacology: A conceptual approach (1st Canadian ed. 2023) by Chippewa Valley Technical College, Amanda Egert, Kimberly Lee and Manu Gill, BCcampus, is used under a CC BY licence.

Introduction to health assessment for the nursing professional (2024) edited by Dr. Jennifer L. Lapum and Michelle Hughes, Toronto Metropolitan University, is used under a CC BY-NC licence.

Nursing fundamentals 2e (n.d.) by Open Resources for Nursing, Chippewa Valley Technical College, is used under a CC BY licence.

Pharmacology for nurses (2024) by Tina Barbour-Taylor, Leah Mueller (Sabato), Donna Paris, and Dorie Weaver, OpenStax, is used under a CC BY licence.

Media Attributions

- Pain Concept Map © Chippewa Valley Technical College, Amanda Egert, Kimberly Lee & Manu Gill adapted by Jessica Best and Eileen Siddins is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Processes of Nociception © Dr Wayne Morriss, Dr Roger Goucke, Dr Linda Huggins & Dr Michael O’Connor adapted by Eileen Siddins is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Ch5-OPQRSTUV © Eileen Siddins is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Wong–Baker Pain Rating Scale © Belbury adapted by Eileen Siddins is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Objective Assessment Techniques © Eileen Siddins is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- PCA Pump © Ben Green is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license