Promoting Sleep

Penelope Coogan and Kate Hurley

Learning Outcomes

In this chapter you will learn how to:

- Identify factors putting people at risk for sleep and rest problems across the lifespan

- Identify cues related to sleep and rest problems

- Identify nonpharmacological interventions to promote sleep and rest

- Contribute to a plan of care for people with sleep and rest alterations

- Recognise the physiological considerations affecting sleep and the influence this can have on one’s health and wellbeing

- Understand the importance of sleep hygiene and recognise the influence common sleep disorders can have on one’s health and wellbeing.

|

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs indicates sleep as one of our physiological requirements. Getting enough quality sleep at the right times according to our circadian rhythms can protect mental and physical health, safety, and quality of life. Conversely, chronic sleep deficiency increases the risk of heart disease, kidney disease, high blood pressure, diabetes, and stroke, as well as weakening the immune system. This chapter will review the physiology of sleep and common sleep disorders, as well as interventions to promote good sleep.

|

What Causes Sleep?

There are two internal biological mechanisms that work together to regulate wakefulness and sleep referred to as circadian rhythms and sleep-wake homeostasis.

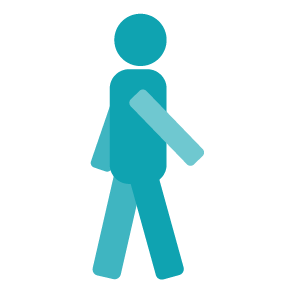

Circadian rhythms direct a wide variety of body functions, including wakefulness, core temperature, metabolism, and the release of hormones. The control of circadian rhythms is initiated within the hypothalamus, where there are centres for sleep and wakefulness. These are set to respond to light and darkness through messages from the retinas. The results include feeling sleepy, physiologically welcoming the onset of sleep two or three hours after dark, and naturally awakening shortly before, or at sunrise.

Sleep-wake homeostasis keeps track of a person’s need for sleep. The pressure to sleep builds with every hour that a person is awake, reaching a peak in the evening when most people fall asleep.

Sleep Phases and Stages

A full sleep cycle takes 80 to 100 minutes to complete, and most people typically cycle through four to six cycles per night. When sleeping, individuals cycle through two phases of sleep:

- Rapid eye movement (REM)

- Non-REM sleep.

Non-REM Sleep

Restoration takes place mostly during slow-wave non-REM sleep, during which the body’s temperature, heart rate, and brain oxygen consumption decrease. Brain activity decreases, so this stage is also referred to as slow-wave sleep and is observed during sleep studies. Non-REM sleep has these three stages:

REM Sleep

During REM sleep, a person’s heart rate and respiratory rate increase. Eyes twitch as they rapidly move back and forth, and the brain is active. Brain activity measured during REM sleep is similar to activity during waking hours. Dreaming occurs during this phase, and muscles normally become limp to prevent acting out one’s dreams. People typically experience more REM sleep as the night progresses. However, hot and cold environments can affect a person’s REM sleep because the body does not regulate temperature well during REM sleep.

Shift Work and Circadian Rhythms

Night shift workers often have trouble falling asleep when they go to bed and may have trouble staying awake at work because their natural circadian rhythm and sleep-wake cycle are disrupted. Jet lag also disrupts circadian rhythms. When flying to a different time zone, a mismatch is created between a person’s internal clock and the actual time of day.

Why Is Sleep Important?

Sleep plays a vital role in good health and well-being. Getting enough quality sleep at the right times protects mental health and physical health. Lack of sleep affects daytime performance, quality of life, and safety. The way a person feels while awake depends on what happens while they are sleeping. During sleep, the body is working to support healthy brain function and maintain physical health.

|

Healthy Brain Function and Emotional Well-Being Sleep helps the brain work properly. While sleeping, the brain is forming new pathways to help a person learn and remember information. Sleep helps a person pay attention, make decisions, and be creative. Conversely, sleep deficiency alters activity in some parts of the brain, causing difficulty in making decisions, solving problems, controlling emotions and behaviour, and coping with change. Sleep deficiency has also been linked to depression, suicide, and risk-taking behaviour.

|

Physical Health

Sleep also plays an important role in physical health. Ongoing sleep deficiency is linked to an increased risk of heart disease, kidney disease, high blood pressure, diabetes, and stroke. Sleep helps maintain a healthy balance of the hormones that cause hunger (ghrelin) or a feeling of fullness (leptin). When a person doesn’t get enough sleep, the level of ghrelin increases and the level of leptin decreases, causing a person to feel hungry when sleep deprived. The way the body responds to insulin is also affected, causing increased blood sugar.

Sleep Patterns Across the Lifespan

Individuals need more sleep early in life when they’re growing and developing. For example, newborns may sleep more than 16 hours a day, and preschool-aged children need to take naps and tend to sleep more in the early evening.

During growth and development phases, sleep patterns change. For example, teenagers fall asleep later at night than younger children and adults because melatonin is released and peaks later in the 24-hour cycle for teens. As a result, it’s natural for many teens to prefer later bedtimes at night and sleep later in the morning than adults. With advancing age, the need for sleep tends to lessen to some extent, from the majority of a twenty-four-hour period to about eight hours. Older adults will tend to go to bed earlier and wake up earlier.

Gender also has some general differences, with men in Stage 1 sleep and waking more times overnight than women. Women tend to take longer entering sleep and spend longer in SWS. Pregnancy and the postpartum period bring their own challenges, with more sleepiness during the day and struggles to find comfortable positions in the advanced stages of pregnancy.

For people in healthcare facilities, sleep and rest patterns may alter due to the effects of their illness/injury, the unfamiliar environment and the disruption of monitoring by healthcare providers.

The different sleep cycles experienced over a lifetime are outlined below.

|

Neonate (0–2 months)

|

|

|

Infant (2–12 months)

|

|

|

|

Toddler (1–3 years)

|

|

Child (3–9 years)

|

|

|

Adolescent (10–18 years)

|

|

|

Young or Middle-Aged Adult (18–65 years)

|

|

Older Adult (65+ years)

|

Physiological Considerations Affecting Sleep

There are various physiological considerations when it comes to sleep. This section explores influences on sleep, including developmental sources, illness, medications, and culture.

Illness

Chronic illness or episodes of acute illness are frequent contributors to disruptions of normal sleep patterns. Some of these circumstances increase sleep, such as when the immune system is combatting an infection or recovering from surgery or trauma. Other circumstances involve less sleep or poor-quality sleep, which does not achieve the rejuvenation and restful state normally associated with sleep. If a person is unable to sleep adequately, sleep is not restorative. Table 2 outlines the way different disorders or conditions can affect an individual’s ability to sleep.

| Disorder | More Sleep | Less Sleep | Notes |

| Bipolar disorder | X | X | Changes in sleep pattern often occurs prior to cycling of manic or depressive episode (especially mania). Depression is associated with an increase or decrease of sleep; mania is associated with decreased sleep. |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) | X | Especially in advanced stages, COPD affects sleep position; it may cause air hunger and frequent awakenings. | |

| Depression | X | X | Depression is commonly accompanied by sleep disorder, with either more or less sleep. |

| Diabetes mellitus (DM) | X | Episodes of poor control (hyperglycaemia) are characterised by polyuria, polydipsia, and polyphagia, which can all disrupt sleep patterns. | |

| Heart failure (HF) | X | Like COPD, in advanced stages, HF affects sleep position, and it may cause air hunger and frequent awakenings. Treatment may cause frequent urination. | |

| Infection | X | X | Infection and related symptoms (e.g., fever, pain, mental status change) may increase or decrease sleep. Sleep may be disrupted and of poor quality. |

| Narcolepsy | X | Narcolepsy is associated with unexpected and sudden sleep episodes during the day. Sleep quality is not necessarily restful or restorative. | |

| Pain | X | Pain often causes sleep disruptions and an inability to sleep deeply. Treatment may cause drowsiness but sleep quality may still be hindered. | |

| Restless leg syndrome (RLS) | X | RLS tends to hinder falling asleep but can also wake a person from sleep. | |

| Sleep apnoea | X | Episodes of apnoea cause frequent awakenings and inhibit achieving deep levels of sleep; restorative rest is reduced. |

Medications

There are some medications designed to assist with sleep and others designed to maintain alertness and stay awake. Medications for sleep work with the central nervous system (CNS) in some capacity, to improve entry to sleep, to help maintain sleep or both. Nurses should engage patients in a discussion about the use of available choices, as a combination of natural supplements or other medications of any sort, should be approved by the healthcare prescriber.

Lifestyle, Habit, and Cultural Considerations

Sleep is an essential component of physical and emotional wellbeing (Gardiner et al., 2023). Certain habits, lifestyle choices, and different cultures can influence sleep, including factors such as physical exercise, age, and lifestyle choices. Sleep quality and quantity change across the lifespan in complex ways due to the ageing process. The need for sleep is continuous throughout a lifetime, but the ability to achieve adequate sleep decreases as a result of the ageing process (Dzierzewski et al., 2021). The ability to fall asleep and stay asleep for long periods can be impacted by lifestyle choices such as the consumption of certain substances and electronic use or physical activity and increased stress. Some of these factors are discussed below.

|

|

Electronic Use Electronics have become a universal part of most lives. For many, electronic connectivity has become such a central part of life they are viewing their screens right before bed and perhaps responding to message alerts when they would previously have been entering deep sleep cycles. Research demonstrates that reading from an electronic device, rather than a printed book, can decrease the feeling of sleepiness and make it more difficult to fall asleep (Dzierzewski et al., 2021). Using an electronic device can impact sleep onset and potentially impact sleep quality due to a reduction of melatonin production due to the additional light exposure (AlShareef, 2022; Casiraghi et al., 2021).

|

Physical Activity

Enhanced sleep quality can lower the risk of developing sleep disorders such as insomnia and can naturally improve sleep health (Alnawwar et al., 2023). Exercise tends to have general health benefits and promote psychophysiological homeostasis. Physical activity contributes to a body’s normal functioning by maintaining flexibility, improving oxygenation and perfusion, and fostering other metabolic actions and reactions. Exercise aids sleep by increasing the production of melatonin, reducing stress and improving mood (Alnawwar et al., 2023). Although an appropriate amount of physical activity is usually associated with positive results, excessive activity may lead to strained muscles or injuries that may cause pain, which can disrupt sleep patterns.

Substances Affecting Sleep

Hospitalisation and Sleep

Since the days of Florence Nightingale, sleep has been recognised as beneficial to health and of great importance during nursing care due to its restorative function. It is common for sleep disturbances and changes in sleep patterns to occur in connection with hospitalisation. Patients in medical and surgical units often report disrupted sleep, not feeling refreshed by sleep, wakeful periods during the night, and increased sleepiness during the day. Illness and the stress of being hospitalised are causative factors, but other reasons for insufficient sleep in hospitals may be due to an uncomfortable bed, being too warm or too cold, environmental noise such as IV pump alarms, disturbance from healthcare personnel and other patients, and pain. The presence of intravenous catheters, a urinary catheter, and drainage tubes can also impair sleep. Increased daytime sleepiness, a consequence of poor-quality sleep at night, can cause decreased mobility and slower recovery from surgery.

Effects of Sleep Deficiency

Insufficient sleep caused by either a total lack of sleep or a lack of quality sleep can affect people in many ways. For children, sleep insufficiency may influence growth and development, and, for both children and adults, sleep inadequacy can have behavioural, psychological, and physiological implications.

Insufficient Sleep in Children

|

Problems sleeping affect 25 to 50 per cent of young children, and approximately 40 percent of adolescents (Pacheco, 2023). If left unmanaged, results of insufficient sleep start to become apparent in growth and development, mental health, behaviour, and performance issues. It also places these children at higher risk for obesity and related health concerns.

|

Growth and Development

Inadequate sleep has direct effects on cognitive operations, alertness, the ability to focus and pay attention, the acquisition of vocabulary, and memory (Liu et al., 2024; Pacheco, 2023). Growth hormone has a relationship to circadian rhythms, with typical release during sleep. In infancy, if sleep is not adequate, it can result in the secretion of insufficient amounts of growth hormone, therefore potentially impacting normal growth at such a critical time (Pacheco, 2023). Chronic lack of growth hormone results in reduced growth, impaired focus and alertness, and inability to regulate moods or positively adapt and develop resiliency. For toddlers, napping is needed to consolidate memories and develop motor skills and high-level attention.

The impact of insufficient sleep on adolescents is seen physically through the development of risk factors for, or diagnosis of, cardiovascular, metabolic, and inflammatory disorders. Hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes mellitus (especially Type 2) are becoming more commonplace in adolescence and even childhood, and insufficient sleep is one major factor (Liu et al., 2024; Pacheco, 2023). Behavioural, mental health, and performance issues in this age group are also associated with sleep insufficiency.

Behavioural and Mental Health Concerns

Insufficient sleep can impact the behaviour and mental health of children in many ways. It has the potential to influence the ability to:

- Pay attention

- Focus

- Plan

- Tolerate frustrating circumstances

- Regulate moods

- Adapt

- Develop resilience.

Depression, anxiety, mood disorders, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) are examples of psychological disorders commonly impacted by lack of sleep (Suni, 2024). Physiological issues that may have a connection to sleep deprivation include cardiovascular, respiratory, gastrointestinal, and metabolic disorders.

Psychological and Cognitive Concerns

Sleep insufficiency is associated with anxiety, depression, concentration, memory, and mood (Suni, 2024). This relationship sometimes occurs in a bidirectional manner, whereby lack of sleep can be both a contributor to and the effect of a mental disorder (Columbia Psychiatry, 2022; Suni, 2024). Even patients who have no history of a mental health disorder might experience issues after episodes of insomnia, especially if the sleep problems become chronic. Psychological distress and insomnia can then become a self-perpetuating problem. Treating a sleep disorder can sometimes improve the mental health problem (Suni, 2024).

Physiological Concerns

Insufficient sleep also affects the body’s physiologic responses or maintenance of homeostasis. Various neurohormonal responses occur during sleep cycles, including healing and restoring actions, as well as the secretion of hormones that sustain normal physiological functions. Sustaining the normal function of the human body involves complex, coordinated activities between the brain and the different organ systems. Sleep is necessary for these systems to perform their necessary tasks and sustain a homeostatic state.

Gastrointestinal

The gastrointestinal system is affected by quantity and quality of sleep, in a bidirectional fashion. Therefore, insufficient or poor sleep can contribute to gastrointestinal disorders, and gastrointestinal problems can result in ineffective sleep (Orr et al. 2020; Vernia et al., 2021). Gastrointestinal distress often leads to fragmented sleep which subsequently, contributes to actual and perceived gastrointestinal symptoms, such as reflux, pain, and bloating. Some of the gastrointestinal disorders commonly exacerbated by lack of sleep include:

- Gastroesophageal reflex disease (GERD)

- Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)

- Irritable bowel disease (IBD)

- Colon cancer

- Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).

There is a pathophysiological relationship observed between obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) and NAFLD.

|

Nutrition is also potentially contributory to gastrointestinal health or illness. Vernia et al., (2021) noted the psychophysiological relationship between a healthy diet, lifestyle and good sleep. Dietary habits such as the following can disrupt sleep:

|

Cardiovascular

The cardiovascular system is particularly sensitive to insufficient sleep and the implications of poor sleep can be seen in:

- Inflammatory responses

- The development of atherosclerosis

- Hypertension

- Hyperlipidaemia

- Hyperglycaemia/diabetes mellitus (DM)

- Obesity

- Myocardial infarction (MI)

- Stroke. (Cleveland Clinic, 2020; Suni, 2023)

More specifically, lack of sleep can result in excess calcium deposited in the coronary arteries and together with hyperlipidaemia and inflammation, contributes to plaque formation which increases the risk of MI and stroke. Chronic hypertension causes stress on the heart and can contribute to MI and heart failure (HF). Depending on the stage of HF, symptoms may include fluid retention and subsequent difficulty breathing. The kidneys and brain are also prone to damage secondary to poor perfusion (Suni, 2023).

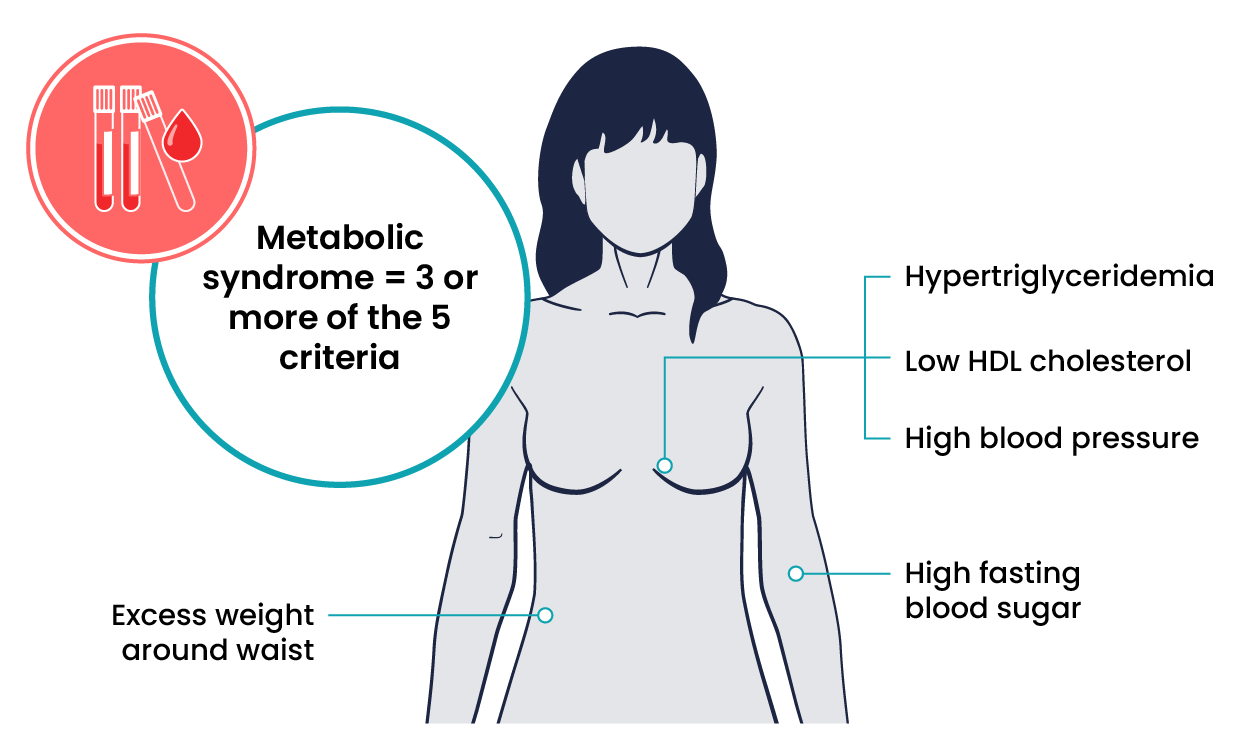

Metabolic Syndrome

Metabolism is influenced by sleep and insufficient sleep in a few ways. The intermittent hypoxia involved in OSA is related to such metabolic disorders as insulin resistance and hyperlipidaemia (Orr et al., 2020).

Diet is also influenced by sleep as the lower levels of the hormones ghrelin and leptin result in not feeling full and food cravings for choices high in fats and carbohydrates.

Lipid abnormalities associated with metabolic syndrome and diabetes mellitus include:

- Combination of high triglycerides and low high-density lipoprotein (HDL)

- Insulin resistance

- Hyperglycaemia

- Hypertension

- Weight gain. (Chasens et al., 2021)

Those who sleep less than five hours, or more than nine hours per day, are at elevated risk of developing metabolic syndrome.

Immunity

Sleep fosters normal immune function, and insufficient sleep is related to both adaptive and innate immune function alterations (Garbarino et al., 2021). Sleep supports the body’s immunological memory. Immune cells are among those produced primarily during sleep (Heid, 2023). Adequate sleep is necessary for the maintenance of normal immune function, homeostasis, the ability to fight microbial invasions, and/or to mount a normal and effective inflammatory response. Patients who do not receive the sleep they need are more susceptible to infections, autoimmune reactions, and exaggerated inflammatory responses, resulting in infections and chronic inflammatory responses. These may include pathological changes in the cardiovascular and metabolic systems, autoimmune and neurodegenerative diseases, and cancers, especially colorectal, prostate, and breast cancers (Garbarino et al., 2021).

Autoimmune disorders, such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and rheumatoid arthritis (RA), are also more common in those who experience chronic sleep loss. Due to chronic illness, the normal immune response becomes unregulated and intensified, causing a more drastic inflammatory response and continuation of chronicity (Garbarino et al. 2021).

Behavioural Effects of Insufficient Sleep

Decision-making can become impaired by lack of sleep, resulting in behaviour changes, including impulsive actions. Misuse of substances and risky, dangerous driving are two potentially damaging behaviours that can be associated with inadequate sleep. Additionally, hypersomnia can negatively affect all different types of behaviours.

Increased Risk for Substance Misuse

Insufficient sleep can have various psychological results, which can then impact behaviour because inadequate sleep can have deleterious effects on clear thinking, coping, and decision-making. Many people self-medicate with substances, such as alcohol, over-the-counter medications, marijuana, and other illicit drugs, to stay awake, fall asleep, and cope with feelings of anxiety, mood changes, frustration, and insecurity. Some look for ways to feel happier, and some search for methods to calm down, even when such relief is temporary and may even result in worsening long-term effects.

Motor Vehicle Accidents

According to the Sleep Health Foundation ([SHF], 2024), driving while drowsy can impair driving performance to a similar level as having a blood alcohol concentration of 0.05%. The SHF statistics suggest that 20-30% of fatal motor vehicle crashes can be attributed to drowsy driving, and up to 1 in 4 single-vehicle accidents on country roads are due to the driver falling asleep. In a 2016 study, it was found that 29% of Australians have driven while drowsy, and 20% reported having fallen asleep while driving (SHF, 2024).

Driving while drowsy is preventable but requires the necessary recognition and respect for its influence on safe driving. The SHF (2024) states that most crashes occur when:

- The driver has had less than 6 hours of sleep

- Has been awake for longer than 17 hours

- Has had less than 3–5 hours of sleep within a 24-hour period.

Common Sleep Disorders

Insomnia

Insomnia is an inability to fall asleep, to stay asleep, or to achieve good quality sleep. Lack of sleep results in feeling fatigued and sleepy, often throughout the day, and can hinder the ability to complete activities and obligations. Insomnia often affects concentration, moods, and energy levels (Roddick & Cherney, 2024). Sleep disruptions are also associated with some cognitive disorders, including Alzheimer’s disease and the risk of developing certain disorders, such as hypertension, coronary artery disease, diabetes mellitus, cancer, depression, and anxiety, is higher for those who experience chronic insomnia. Sleep problems can occur at any age but most commonly start in young adulthood (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2024).

Insomnia can be acute or chronic. Acute or short-term insomnia is temporary and may occur in response to a stressful situation or a change to a person’s sleep schedule, such as a later night than usual or having to get up earlier than expected. Chronic insomnia lasts longer than three months and/or occurs more than three nights per week.

Symptoms of Insomnia

- Lying awake for a long time before falling asleep.

- Sleeping for only short periods due to waking up often during the night or being awake for most of the night.

- Waking up too early in the morning and not being able to get back to sleep.

- Experiencing poor quality of sleep that causes one to wake up feeling unrested.

Diagnosis

To be diagnosed with insomnia, a comprehensive assessment must be completed, including a physical exam, a sleep diary and clinical testing. For a sleep assessment to take place, sleep difficulties must occur at least three nights a week for at least three months and cause significant distress or problems at work, school or other important areas of a person’s daily functioning (APA, 2024).

Management and Treatment

|

Lifestyle changes often help improve the quality of sleep due to short-term insomnia. Good sleep hygiene is recommended for those suffering from insomnia, including:

|

Link to Learning

Parasomnia

Parasomnias are abnormal behaviours while a person is asleep, such as dreams, movement and vocalisation while the person is falling asleep or sleeping. With many of the parasomnia behaviours, the person does not remember the activities. Associated dreams may be recalled immediately upon waking, but most are not remembered long-term. There is an almost cyclical relationship between insomnia and parasomnias, as lack of sleep can contribute to the occurrence of parasomnias, and parasomnias may result in a lack of sleep.

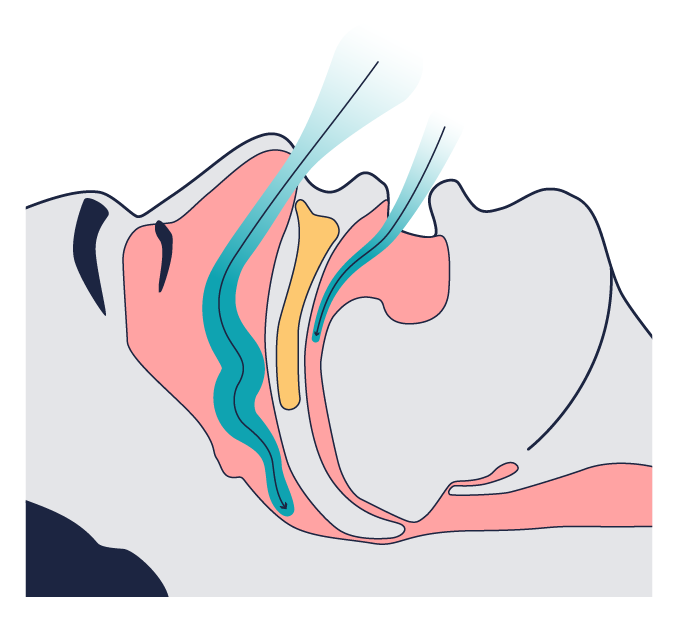

Obstructive Sleep Apnoea (OSA)

OSA is common and involves the relaxation of the muscles of the posterior pharynx (back of the throat; see Figure 5.) and presents as repeated episodes of snoring, snorting, gasping or breathing pauses (APA, 2024). If these muscles relax excessively, they do not support structures within the mouth and throat, including the soft palate, tongue, and sides of the throat, which can compromise airflow. The impaired breathing causes an accumulation of carbon dioxide (CO2), which, upon reaching a certain level, causes the brain to wake the individual, open the airway, and take a deep breath. Depending on the level of CO2 and oxygen (O2), it may take a few deep breaths to normalise the blood gases. Many people have no recollection of the frequent awakenings as they return to sleep quickly. Nonetheless, if their sleep is disrupted several times each hour, it fragments their sleep, and they may be very drowsy during the day, have mood swings, and find it difficult to concentrate on tasks and thoughts.

Symptoms of OSA

- Reduced or absent breathing, known as apnoea events

- Frequent loud snoring

- Gasping for air during sleep

- Excessive daytime sleepiness and fatigue

- Decreases in attention, vigilance, concentration, motor skills, and verbal and visuospatial memory

- Dry mouth or headaches when waking

- Sexual dysfunction or decreased libido

- Waking up often during the night to urinate.

|

Management and Treatment

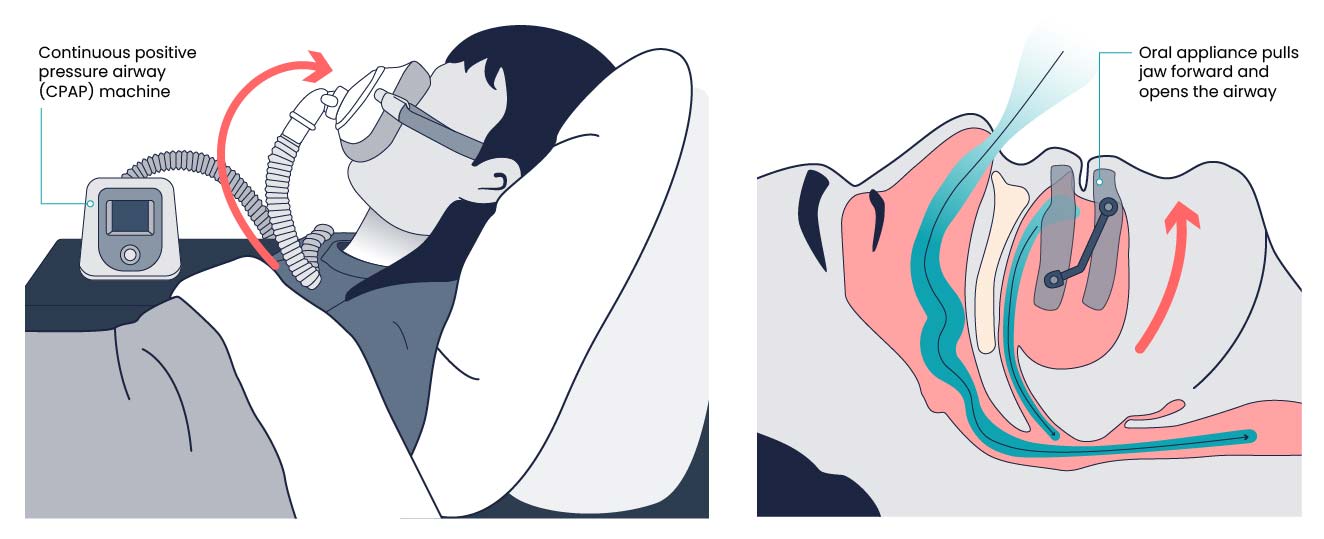

Continuous positive pressure airway (CPAP) is a breathing device commonly prescribed to treat OSA. This device uses mild pressure to keep the airways open while the person is sleeping. Figure 6 below depicts a CPAP machine and how it attaches to a patient. A mouthpiece and oral appliance (Figure 6) are devices that are prescribed to assist individuals with mild OSA. The oral appliance is custom-fit to prevent the jaw or tongue from occluding the airway while a person is sleeping. gives examples of common mouth or oral appliances used for patients with mild OSA.

|

Central Sleep Apnoea (CSA)

CSA is less common than OSA. It involves a lack of communication between the brain stem and the muscles involved in breathing as the airway remains open, but the impaired messaging causes frequent apnoeic episodes throughout a sleep cycle (APA, 2024). Patients with CSA tend to experience the same fragmented sleep as those with OSA, but they also may notice nighttime discomfort in the chest, headaches in the morning, and insomnia.

Narcolepsy

Narcolepsy is an uncommon sleep disorder that causes periods of extreme daytime sleepiness and sudden, brief episodes of deep sleep during the day. People with narcolepsy have episodes of cataplexy, a brief, sudden loss of muscle tone triggered by laughter or joking. This can result in head bobbing, jaw-dropping, or falls. Individuals are awake and aware during cataplexy (APA, 2024).

Narcolepsy is rare, affecting less than 1% of the adult general population. It typically begins in childhood, adolescence or young adulthood (APA, 2024). Narcolepsy is diagnosed based on medical history, family history, a physical exam, and a sleep study. The sleep study looks at daytime naps to identify disturbed sleep or a quick onset of rapid eye movement (REM) sleep.

Symptoms of Narcolepsy

- Extreme daytime sleepiness

- Falling asleep without warning

- Difficulty focusing or staying awake during the day

- Frequent night waking

- Hallucinations

- Sleep paralysis (lying awake and unable to move for several minutes).

|

Management and Treatment

|

Other Sleep Disorders

There are several other breathing disorders associated with sleep as well. Sleep-related hypoventilation means shallow and unusually slow respirations while asleep. Such inadequate breathing allows for the patient to develop hypercapnia, or elevated blood CO2. Sleep-related hypoxaemia (low level of O2 in the blood) is typically not a primary disorder but the result of another condition, usually respiratory, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Diagnostic Testing for Sleep Disorders

Sleep Study

A sleep study may be ordered for an individual suspected of having a sleep disorder and can be performed at a specialist centre or in the patient’s home. Polysomnography simultaneously records physiologic monitoring, including EEG for recording brain waves, ECG for the electrical cardiac cycle, EOG for recording eye movements, EMG for recording muscle movements, and SaO2. Monitoring leads for this recording are placed at locations on the scalp, face, eyelids, chest, and limbs, and a pulse oximeter is placed on a finger. Results display on a hypnogram and contribute to diagnosis of insomnia, sleep apnoea, narcolepsy, somnambulism, and RLS. See Figure 7 for an image of a patient with sensors in place for a sleep study.

Assessment for Sleep Disturbances

Initial Data Collection

Nurses play an important role in caring for patients with sleep disturbances. Through the data collection (assessment) phase, patient education to improve sleep, and medication administration and education, nurses are involved directly in engaging with patients. Nursing assessment should also include inquiry as to any changes the patient has noticed—psychologically or physiologically—that could be a result of the lack of sleep. The patient may have made the connection or may not have considered sleep as the root of the changes. The nurse may be the first to recognise the link, particularly if already familiar with disorders that are often related to sleep disturbances.

Assessment and Education

Nurses can gather vital information about a patient’s personal and family history, advise about keeping a sleep log, and provide information about sleep studies for those who are prescribed such diagnostic testing. The role of the nurse often includes educating patients about issues they are experiencing and ideally helping identify methods to improve problems.

Nursing care begins with the assessment—gathering necessary and helpful information upon which to build care planning—and continues with prioritising patient problems, identifying ways to approach them, implementing the identified actions, and evaluating the outcome(s). In the case of sleep disturbances, data collection begins with a detailed family and personal history focused on particular factors that may influence rest and sleep.

Patient Assessment

Patients who have been experiencing insufficient sleep are often asked to keep a sleep log, and the nurse is able to analyse this diary of events, providing important information to the prescriber. Some patients are prescribed a sleep study, and nurses can educate the patient prior to such a study and assist with post-study follow-up with the patient and family if indicated.

|

Collect a Detailed History Family and patient history, including diagnoses, surgeries, and medications, is a starting point for assessment. The nurse should perform a focused assessment, exploring sleep patterns, hours of sleep, and whether the patient or significant other reports loud snoring or apnoeic periods followed by episodes of gasping as the body works to recover from the apnoea-related hypoxia. For those who work nights, times for sleep may need to be adjusted, or follow-up questions may be added about time at work versus time off. It is also helpful to determine the effects of caffeine intake and medications on a patient’s sleep pattern. If a patient provides information causing concern for impaired sleep patterns or a sleep disorder, it is helpful to encourage them to create a sleep diary to share with a healthcare provider. Nurses also perform objective assessments of a patient’s sleep patterns during inpatient care. The number of hours slept, wakefulness during the night, and episodes of loud snoring or apnoea should be documented. Note physical (e.g., sleep apnoea, pain, and urinary frequency) or psychological (e.g., fear or anxiety) circumstances that interrupt sleep, as well as sleepiness and napping during the day.

|

The table below includes guiding questions and can be modified to fit the practice needs of individual nurses.

| Questions | Normal Findings |

| How many hours do you sleep on an average night? | 7–8 hours for adults |

| During the past month, how would you rate your sleep quality overall? | Very good or fairly good |

| Do you go to bed and wake up at the same time every day, even on weekends? | Yes, they generally maintain a consistent sleep schedule |

| How likely is it for you to fall asleep during the daytime without intending to? Do you struggle to stay awake while you are doing things? | Unlikely |

| How often do you have trouble going to sleep or staying asleep? | Never, rarely, or sometimes |

| During the past two weeks, how many times did you have loud snoring while sleeping?

Note: It is helpful to ask the patient’s sleep partner this question. |

Never |

Good Sleep Hygiene

Sleeping whilst unwell or receiving medical treatment in a healthcare setting is difficult. As healthcare practitioners, there are some interventions we can put in place to improve sleep hygiene for those in our care.

- Close window curtains if external light shines through

- Close curtains between people to create a feeling of privacy

- Reduce or eliminate overhead lighting and provide a night light if light overnight is necessary

- Use a torch to check on patients, including checking drainage bags to limit disruptions

- Ensure a clear pathway around the bed to avoid bumping into personal belongings or hospital equipment to avoid disrupting sleep

- Close the door to the room if possible

- Be mindful of noise made in communal staff areas, such as ringing phones, paging systems, and communication between staff

- Perform only essential tasks during sleeping hours or while patients are resting.

Sleep cycles are a complex process managed by specialised areas in the brain stem and are influenced by an individual’s circadian rhythm. Regular, sufficient sleep is needed for optimal physiological and psychological functioning. Insufficient sleep can disrupt functional ability, adversely impacting overall health.

Key Takeaways

In this chapter, we covered:

- Circadian rhythms and sleep-wake homeostasis are the two internal biological mechanisms that work together to regulate sleep and wakefulness.

- A full sleep cycle takes between 80-100 minutes to complete, and most people typically cycle through four to six cycles per night. When sleeping, individuals cycle through two phases of sleep – REM and non-REM sleep.

- While sleeping, the brain is forming new pathways to allow a person to learn and remember, helping a person to be attentive, make decisions and be creative while awake.

- Many factors can affect the quality and quantity of sleep, including illness, physical activity, mental status, substance use, stress and culture.

- Insufficient sleep can affect growth and development, behavioural and mental health, psychological and cognitive functioning, anxiety, depression, concentration and mood. It can also negatively affect the gastrointestinal system, cardiovascular system, and immunity.

References

AlShareef, S. M. (2022). The impact of bedtime technology use on sleep quality and excessive daytime sleepiness in adults. Sleep Science, 15(2), 318–327. https://doi.org/10.5935/1984-0063.20200128

Alnawwar, M. A., Alraddadi, M. I., Algethmi, R. A., Salem, G. A., Salem, M. A., Alharbi, A. A. (2023). The effect of physical activity on sleep quality and sleep disorder: A systematic review. Cureus, 16(15), Article e43595. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.43595

American Psychiatric Association. (2024). What are sleep disorders? https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/sleep-disorders/what-are-sleep-disorders

Casiraghi, L., Spiousas, I., Dunster, G. P., McGlothlen, K., Fernández-Duque, E., Valeggia, C., & de la Iglesia, H. O. (2021). Moonstruck sleep: Synchronization of human sleep with the moon cycle under field conditions. Science Advances, 7(5), Article eabe0465. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abe0465

Chasens, E. R., Imes, C. C., Kariuki, J. K., Luyster, F. S., Morris, J. L., DiNardo, M. M., Godzik, C. M., Jeon, B., & Yang, K. (2021). Sleep and metabolic syndrome. The Nursing Clinics of North America, 56(2), 203–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cnur.2020.10.012

Cherry, K. (2023). Effects of lack of sleep on mental health. Verywell Mind. https://www.verywellmind.com/how-sleep-affects-mental-health-4783067

Cleveland Clinic. (2020). Why you need to get enough sleep for a healthy heart. https://health.clevelandclinic.org/for-a-healthy-heart-get-enough-sleep

Columbia Psychiatry. (2022). How sleep deprivation impacts mental health. https://www.columbiapsychiatry.org/news/how-sleep-deprivation-affects-your-mental-health

Dzierzewski, J. M., Sabet, S. M., Ghose, S. M., Perez, E., Soto, P., Ravyts, S. G., Dautovich, N. D. (2021). Lifestyle factors and sleep health across a lifespan. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(12). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126626

Garbarino, S., Lanteri, P., Bragazzi, N. L., Magnavita, N., & Scoditti, E. (2021). Role of sleep deprivation in immune-related disease risk and outcomes. Communications Biology, 4(1), 1304. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-021-02825-4

Gardiner, C., Weakley, J., Burke, L.M., Roach, G. D., Sargent, C., Maniar, N., Townshend, A., & Halson, S. L. (2023). The effect of caffeine on subsequent sleep: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Medicines Review, 69, Article 101764. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2023.101764

HealthMatch. (2022). Hallucinations caused by insomnia: What you need to know. https://healthmatch.io/insomnia/hallucinations-caused-by-insomnia

Heid, M. (2023). Why sleep is so important for a healthy immune system. Everyday Health. https://www.everydayhealth.com/sleep/why-sleep-is-so-important-for-a-healthy-immune-system/

Johnson, N. (2024). Baby sleep cycles by age chart. The Baby Sleep Site. https://www.babysleepsite.com/baby-sleep-patterns/baby-sleep-cycles-by-age-chart/

Krans, B. (2019). Why alcohol, nicotine disrupt your sleep more than coffee. Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health-news/it-might-not-be-the-coffee-that-causes-you-to-wake-up-during-the-night

Liu, J., Ji, X., Pitt, S., Wang, G., Rovit, E., Lipman, T., & Jiang, F. (2024). Childhood sleep: Physical, cognitive, and behavioral consequences and implications. World Journal of Pediatrics, 20(2), 122–132. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12519-022-00647-w

Lockett, E. (2023). Everything to know about the stages of sleep. Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health/healthy-sleep/stages-of-sleep

Nunez, K. & Lamoreux, K. (2023). What is the purpose of sleep? Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health/why-do-we-sleep#restoration

Orr, W. C., Fass, R., Sundaram, S. S., & Scheimann, A. O. (2020). The effect of sleep on gastrointestinal functioning in common digestive diseases. The Lancet Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 5(6), 616–624. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30412-1

Patel, A. K., Reddy, V., Shumway, K. R., & Araujo, J. F. (2024). Physiology, sleep stages. In W. B. Ackley, T. S. Adolphe, T. C. Aeby, N. R. Aeddula, S. Agadi, P. Agasthi, S. Ahmad, A. Ahmed, F. W. Ahmed, I. Ahmed, R. A. Ahmed, S. W. Ahmed, A. M. Akanmode, R. Akella, S. M. Akram, Y. Al Khalili, E. Al Zaabi, M. H. Alahmadi, G. Alexander, … H. Zulfiqar (Eds). StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved March 18, 2025 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526132/

Pacheco, D. (2023). Children and sleep. Sleep Foundation. https://www.sleepfoundation.org/children-and-sleep

Peters, B. (2023). Tips for staying awake when you’re tired. Verywell Health. https://www.verywellhealth.com/tips-for-staying-awake-3015057

Roddick, J. & Cherney, K. (2024). Sleep disorders. Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health/sleep/disorders

Sleep Health Foundation. (2024). Caffeine and sleep. https://www.sleephealthfoundation.org.au/sleep-topics/caffeine-and-sleep

Spadola, C. E., Guo, N., Johnson, D. A., Sofer, T., Bertisch, S. M., Jackson, C. L., Rueschman, M., Mittleman, M. A., Wilson, J. G., & Redline, S. (2019). Evening intake of alcohol, caffeine, and nicotine: Night-to-night associations with sleep duration and continuity among African Americans in the Jackson Heart Sleep Study. Sleep 42(11):zsz136. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsz136

Suni, E. (2024). Mental health and sleep. Sleep Foundation. https://www.sleepfoundation.org/mental-health

Vernia, F., Di Ruscio, M., Ciccone, A., Viscido, A., Frieri, G., Stefanelli, G., & Latella, G. (2021). Sleep disorders related to nutrition and digestive diseases: A neglected clinical condition. International Journal of Medical Sciences, 18(3), 593–603. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijms.45512

Chapter Attribution

This chapter has been adapted in parts from:

Fundamentals of nursing (2024) edited by Christy Bowen, Lindsay Draper and Heather Moore, OpenStax, is used under a CC BY licence.

Media Attributions

- Master Circadian Clock © I. B. Hickie, S. L. Naismith, R. Robillard, E. M. Scott & D. F. Hermens is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Hospitalisation and Sleep © Ben Green is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Metabolic Syndrome © Eileen Siddins is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Sleep and Immune Functioning © Ben Green is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Patient With OSA © Habib Mhenni adapted by Eileen Siddins is licensed under a Public Domain license

- CPAP Maching and Oral Appliance © Eileen Siddins is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Sleep Study Patient © Joe Mabel is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Sleep Hygiene © Ben Green is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license