Recognising and Responding to the Deteriorating Patient

Tracey Gooding and Jessica Best

Learning Outcomes

In this chapter, you will learn how to:

- Conduct comprehensive safety checks and identify potential hazards to ensure readiness for patient deterioration

- Predict potential complications and develop strategies to prevent or prepare for patient deterioration

- Recognise and escalate patient deterioration, including physiological and psychological acute deterioration

- Perform emergency assessments on the deteriorating patient, including a primary and secondary survey

- Apply effective communication techniques such as ISBAR to escalate and hand over care of the deteriorating patient, PACE for graded assertiveness and closed-loop communication

- Perform Basic Life Support (BLS) procedures, including the steps of DRSABCD, to provide immediate and effective care in emergency situations for adult and paediatric patients

- Discuss the importance of Advanced Resuscitation Plans and transitioning to end-of-life care when appropriate for the deteriorating patient.

Introduction

In the often unpredictable healthcare environment, a nurse’s ability to recognise and respond to a deteriorating patient is a crucial skill. Early recognition and timely interventions can significantly improve patient outcomes, reduce length of stay, and prevent adverse events. This chapter aims to equip nurses with the knowledge and skills to prevent and predict deterioration, identify early signs of patient deterioration, effectively respond and escalate care of the deteriorating patient, and implement appropriate assessment and management strategies in emergency situations, including end-of-life care.

Why Early Intervention Matters

In 2023, 28,112 deaths in Australia were classified as potentially avoidable (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2024). Enhancing the early detection of patient deterioration and ensuring timely interventions are important strategies for addressing this issue. Research highlights that many adverse outcomes could be mitigated if early warning signs were more effectively identified and acted upon (Massey et al., 2017), underscoring the need for continued focus on proactive patient care to predict, recognise and respond appropriately to patient deterioration and system improvements.

Links to Learning

These insights contributed to establishing a national standard in Australia: Standard 8 – Recognising and Responding to Acute Deterioration Standard, the Australian National Consensus Statement: Essential elements for recognising and responding to acute physiological deterioration and the Australian National Consensus Statement: Essential elements for recognising and responding to deterioration in a person’s mental state.

These documents highlight the importance of promptly recognising physical and cognitive deterioration signs and provide a guide to identifying deterioration and instigating an effective clinical response. The objective is to ensure that these warning signs are detected early and that qualified healthcare professionals carry out timely, effective interventions to improve patient outcomes.

Factors Influencing Early Intervention

Research by Anstey et al. (2019) revealed that a significant number of nursing staff believed that the Recognising and Responding to Acute Deterioration standard has improved the recognition and response to deteriorating patients in their health service with the most cited benefits being enhanced vital signs monitoring, increased escalation of care and improved ward management of the deteriorating patient. A large Australian focus group study identified that a standardised approach, workplace culture and teamwork, confidence and experience and communication were considered vital to responding and escalating care of the deteriorating patient (Newman et al., 2023).

The implementation of Rapid Response Systems(RRSs) was another response to the statistics on deteriorating patients as they were adopted throughout Australia and continue to provide a safety net to identify deteriorating patients and ensure they receive appropriate care (Clinical Excellence Commission, n.d.). RRSs provide a structured approach to responding to patients experiencing acute clinical deterioration. Its primary goal is to prevent adverse events, such as cardiac arrest, unplanned intensive care unit (ICU) admissions, or death, by intervening early when warning signs of deterioration are identified. Knowing when and how to escalate care through this standardised system is an important factor in its success.

A trigger mechanism such as an Early Warning Score (EWS), may be used to detect deterioration first, and then escalation of care occurs through a standardised communication platform such as a number to call or a paging system, to a team of multi-disciplinary practitioners experienced in recognising and responding to deterioration. These teams are usually known as Rapid Response Teams (RRT) or Medical Emergency Teams (MET). Research has shown a correlation between implementing RRSs and reductions in in-hospital mortality and cardiac arrest rates. These findings highlight the effectiveness of RRSs in improving patient safety and outcomes within hospital settings (Jones, 2023).

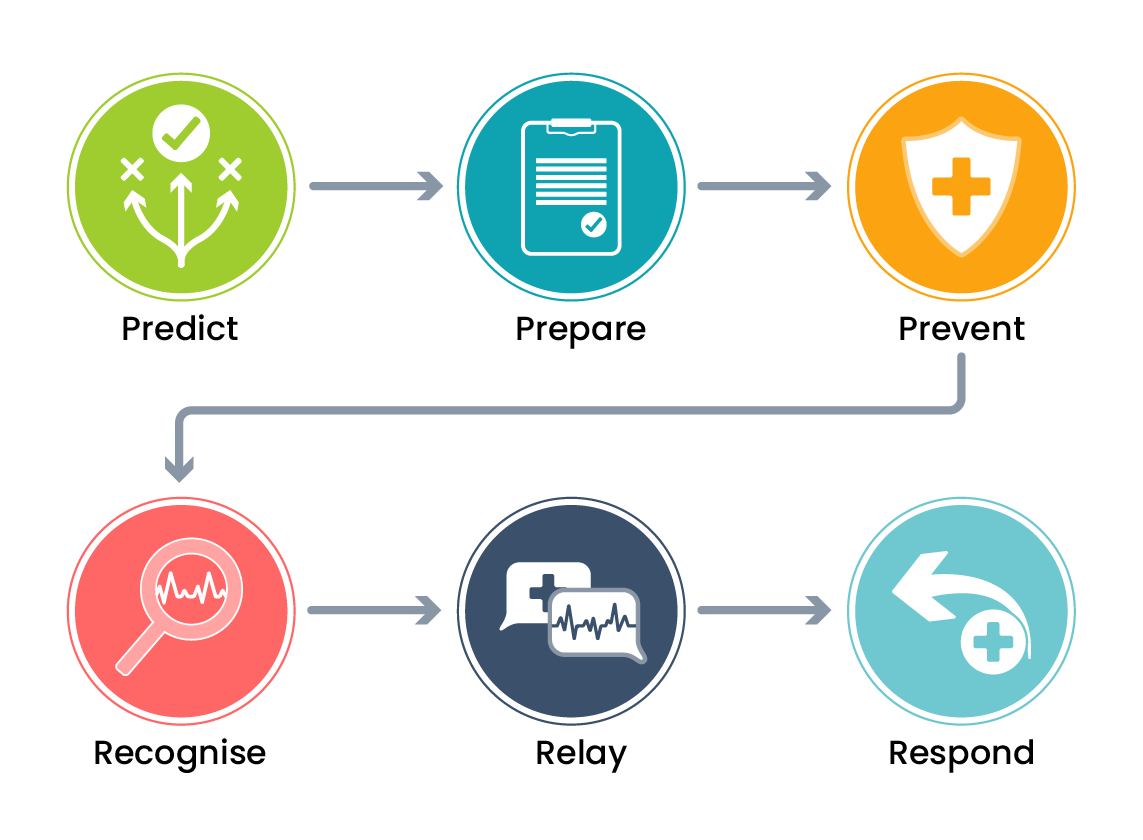

Since nurses are the healthcare professionals most frequently responsible for assessing vital signs, the effectiveness of hospital rapid response systems (RRSs) largely relies on their ability to perform accurate patient assessments, interpret data correctly, and escalate care when signs of deterioration are detected (Chua et al., 2019; Considine & Currey, 2015; Padilla & Mayo, 2018). Although vital signs are heavily relied upon to identify clinical deterioration and trigger a response for deteriorating patients in hospital settings, nurses’ documentation of vital signs and their use in activating rapid response systems remain poorly understood (Considine et al., 2024). This highlights the vital role that education and training for ward staff have in ensuring early detection of the deteriorating patient and triggering escalation of care. Understanding the steps and strategies that can prevent a failure to recognise and respond to acute deterioration, is crucial for improving patient outcomes, enhancing quality of care, and reducing preventable deaths in healthcare settings. These steps can be summarised as the 3Ps and 3Rs: predict, prepare, prevent, recognise, relay and respond.

The 3Ps and 3Rs

Predict

|

|

In the presence of known problems, nurses must predict the most common and dangerous complications associated with each problem and proactively prepare for potential worst-case scenarios. By analysing patterns and trends in vital signs, laboratory results, and other data, clinicians can identify patients at risk of deterioration before it occurs. Prediction requires healthcare professionals to anticipate potential complications or risks based on patient history, current condition, and clinical trends. The nurse must always be thinking two steps ahead. While it sounds daunting, most people use this thinking in daily life without realising it.

|

For novice nurses, developing this foresight begins with building a strong foundation of clinical knowledge and critical thinking skills. It involves learning to recognise patterns, understanding the progression of various conditions, and familiarising oneself with evidence-based practices. Moreover, fostering effective communication and collaboration with the healthcare team ensures that potential issues are addressed collaboratively and efficiently. Over time, with experience and reflection, this proactive approach becomes second nature, enabling nurses to provide high-quality, responsive care that prioritises patient safety.

Prepare

|

Being prepared for emergencies is a critical aspect of nursing care, especially when managing deteriorating patients. Preparation involves ensuring that you have the necessary resources, training, and systems to identify and respond effectively to patient deterioration.

|

Safety Checks

Before assessing a patient, it is crucial to ensure that you are fully prepared for any potential emergencies or deterioration. This involves conducting pre-emptive safety checks and ensuring that all necessary equipment and resources are readily available and in working condition. Preparedness can make a significant difference in the speed and effectiveness of your response to a deteriorating patient.

Pre-emptive safety checks are essential to create a safe environment for both patients and healthcare providers. These checks help identify and mitigate potential hazards, ensuring that the care team is ready to respond to any emergencies. Key steps in conducting pre-emptive safety checks include:

Resource Management

Resource management focuses on the efficient allocation, availability and maintenance of both medical and non-medical resources that may be needed in an emergency. Having the right equipment and resources readily available is vital for managing emergencies effectively. Key considerations include:

Prevent

|

In the previous step, nurses must consider the many possible scenarios that occur as a result of patient deterioration. Prevention involves carefully implementing measures to prevent further deterioration and adverse events from occurring. Early detection and appropriate interventions can prevent or significantly reduce the risk of adverse outcomes in deteriorating patients. Studies have long revealed that in many instances these events were preceded by objective signs of clinical deterioration prior to the event (Hodgetts et al., 2002; McQuillan et al., 1998).

|

Many strategies have been implemented Australia-wide to reduce the risk of missing signs of deterioration and/or not escalating care for a deteriorating patient. The national standard designed to improve the recognition of, and response to deteriorating patients in acute health care facilities requires that all hospitals have a Rapid Response System (RRS), and provide initiatives that improve the detection of clinical deterioration in the period prior to Rapid Response Team (RRT)/Medical Emergency Team (MET) activation (Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care [ACSQHC], 2024b).

Key strategies for preventing further deterioration and adverse events include utilising Early Warning Scores (EWS), utilising relevant algorithms, following protocols and clinical pathways, having knowledge of the escalation protocols, and implementing rapid response systems when indicated.

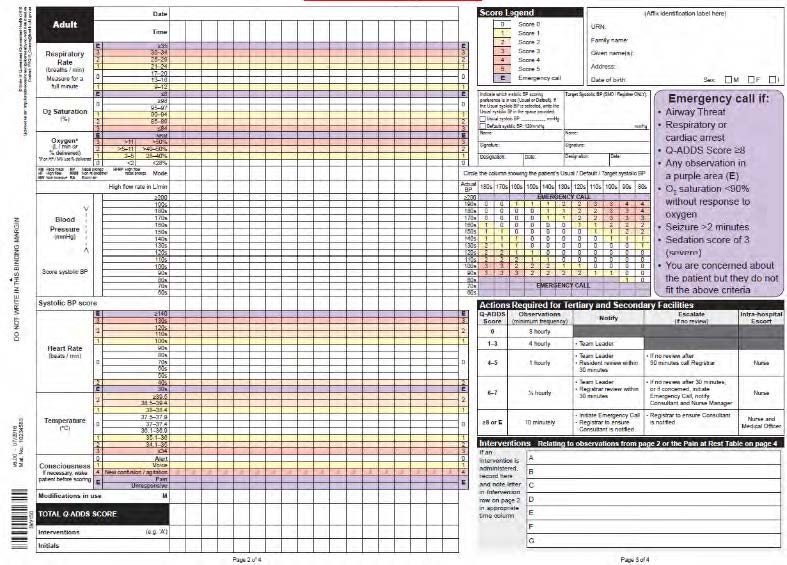

Early Warning Scores (EWS)

Studies have demonstrated that utilising EWSs can effectively prevent unrecognised deterioration (Crowe et al., 2018; Warren et al., 2021). EWSs equip nurses with a tool to identify patient deterioration trends earlier for more timely interventions (Ashbeck et al., 2021). Utilising EWSs, such as the Queensland Adult Deterioration Detection System (Q-ADDS), Queensland Maternity Early Warning Tool (Q-MEWT), Children’s Early Warning Tool (CEWT), Modified Early Warning Score (MEWS) or National Early Warning Score (NEWS), helps identify patients at risk of deterioration. The observation chart includes graphical information which is helpful in tracking trends over time. The scoring systems use vital signs and clinical parameters to generate an overall score that triggers specific actions based on the level of risk and clearly indicates when escalation should occur (ACSQHC, 2021; Ashbeck et al., 2021; Le Lagadec & Dwyer, 2017). Scores are colour-coded to clearly indicate different levels of escalation. See Figure 3 for an example of a MEWS chart.

|

Yellow zone

|

|

Red zone

|

|

Purple zone

|

It is worth noting that while research indicates that early warning systems can assist clinicians in making decisions about escalating care, experts warn that due to the influence of human factors in the decision-making process, EWS charts should not be relied upon as a substitute for sound clinical judgment (Le Lagadec & Dwyer, 2017).

Algorithms, Protocols and Clinical Pathways

In order to prevent further deterioration in a patient, consideration needs to be given to the underlying cause. By applying algorithms, protocols, and clinical pathways that correspond to specific diagnoses such as sepsis, stroke, delirium, anaphylaxis, cardiac arrhythmias and myocardial infarction, response systems can be customised to fit the individual patient’s situation and can ensure the involvement of specialists with skills and expertise in managing that particular condition (ACSQHC, 2021).

Escalation Protocols

Knowing the escalation protocols within the organisation and triggering these escalation pathways when appropriate helps ensure that any signs of deterioration are treated with the appropriate nursing intervention and/or promptly communicated to the appropriate healthcare providers. This might be recommended as per the EWS or particular algorithm, protocol or clinical pathway you may be following. EWS charts will offer recommendations to escalate care as indicated for each score. This might include increased monitoring, notifying the nurse in charge, notifying or escalating review by a medical officer, or calling for an emergency response. This may also include transferring the patient to a higher level of care within or external to your facility. Despite the use of pathways and EWS recommendations, clinicians can also escalate care anytime, based on their own clinical judgement or the concerns of the family or carer. Each organisation will have their own formal, organisation-wide escalation protocol that can be triggered for all patients at any time (ACSQHC, 2021). Knowing how this is done is paramount to the safety of the deteriorating patient.

Rapid Response Systems (RRS)

Implementing RRS, such as Medical Emergency Teams (MET) or Rapid Response Teams (RRT), ensures that trained and experienced clinicians can quickly assess and manage patients showing signs of deterioration. These teams are trained to provide immediate and advanced life-saving care, stabilise patients, and prevent further decline.

Ryan’s Rule

Families and caregivers often notice subtle signs of deterioration before healthcare staff do, which is why Ryan’s Rule was introduced in Queensland to empower them to escalate concerns and ensure timely medical intervention when a patient’s condition worsens. Other Australian states have similar escalation systems, but they may have different names. This rule allows patients, families, and caregivers to escalate concerns about a patient’s condition if they feel their concerns are not being taken seriously by healthcare staff.

|

Why Ryan’s Rule was created It was introduced after the death of Ryan Saunders, a two-year-old boy who passed away from an undiagnosed streptococcal infection in 2007. His parents had concerns about his condition, but their concerns were not escalated appropriately. Ryan’s Rule was implemented to ensure that similar situations do not happen again. How Ryan’s Rule works If a patient’s condition is worsening and concerns are not being addressed, they can take the following steps:

An independent senior clinician will then conduct a Ryan’s Rule Clinical Review to assess the situation. You can learn more about Ryan’s Rule on this web page. (Queensland Government, 2024)

|

Recognise

|

Recognition involves identifying early signs of patient deterioration through vigilant monitoring and assessment. Nurses play a vital role in this recognition of subtle changes in vital signs, behaviour, or clinical conditions. Rapid recognition of these warning signs is essential to initiate timely interventions and improve patient outcomes. Understanding the key physiological indicators and clinical symptoms that nurses should be vigilant about when assessing patients can significantly enhance early detection of deterioration.

|

Physiological indicators are objective measurements that can signal a patient’s deterioration. These indicators often involve changes in vital signs and other measurable parameters. Key physiological indicators include vital signs. In Australia, a complete set of vital signs comprises the following (ACSQHC, 2021):

New Onset Confusion or Behaviour Change

According to the ACSQHC (2017), new onset confusion is characterised by a sudden shift in a person’s mental state, often signalling the presence of delirium. This condition develops rapidly, typically over a matter of hours or days, and is distinct from any pre-existing cognitive impairment. Patients experiencing new onset confusion may exhibit (ACSQHC, 2017):

- Impaired attention, making it difficult for the patient to focus or follow conversations

- Altered consciousness, which can range from increased drowsiness to heightened agitation

- Disorganised thinking, leading to incoherent speech, difficult reasoning, or unpredictable behaviour.

Because delirium can be caused by various underlying condition, such as infection, metabolic imbalances, medication effects, or organ dysfunction, it is essential to conduct a prompt and thorough evaluation to determine the cause and initiate appropriate treatment.

Relay

|

Effective communication or “relaying” information ensures that critical information about a patient’s condition is accurately and promptly shared among healthcare team members and escalated in a timely manner. Communication plays a crucial role in coordinating resources to the bedside when a patient begins to deteriorate (Manojlovich & Krein, 2022; Newman et al., 2023). Inadequate escalation efforts due to poor communication techniques expose patients to serious harm, highlighting the need for interventions to enhance communication efforts (Burke et al., 2022). Relaying information about patient deterioration can take various forms. There are many communication tools and techniques used in healthcare to assist with effective communication.

|

ISBAR

Structured tools such as ISBAR (Identification, Situation, Background, Assessment and Recommendations) can help improve the nurse’s confidence, clarity and urgency of messages when escalating care (Burgess et al., 2020). Click or tap through each stage of the ISBAR handover below to understand each element of this structured approach.

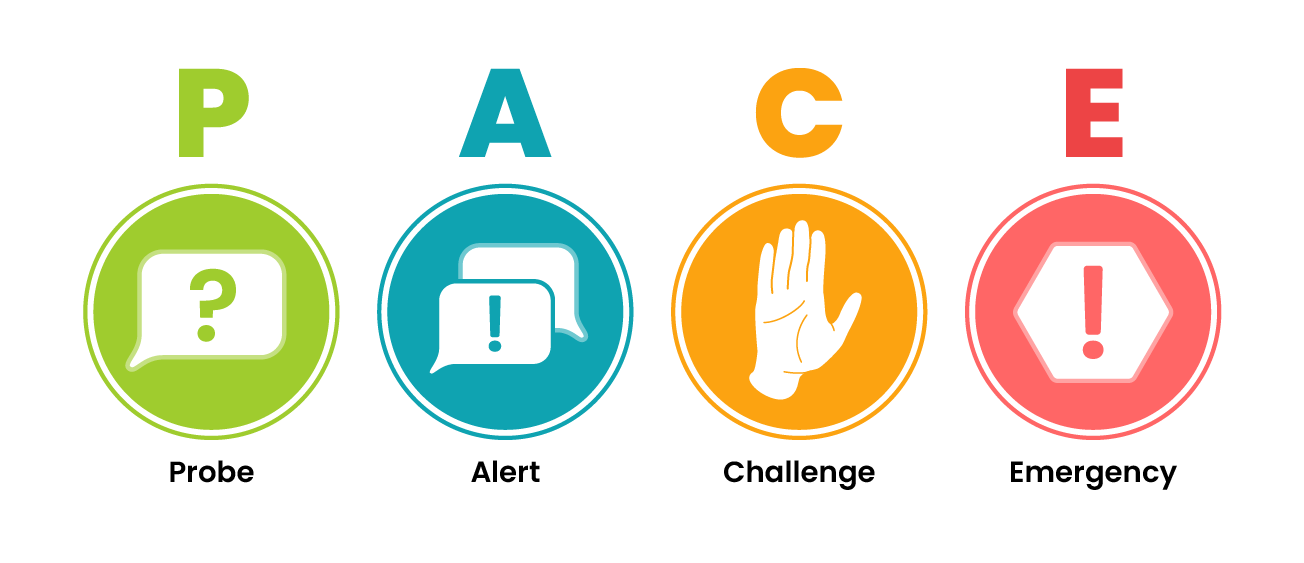

PACE

PACE (Probe, Alert, Challenge and Emergency) is a communication tool often used for graded assertiveness in healthcare. Fear of criticism or reprimand can prevent nursing staff from voicing concerns, especially in a culture that is hierarchical and discourages open communication, collaboration, or the empowerment of junior staff. This environment can contribute to failure to recognise and respond to deterioration (Burke et al., 2022).

|

Probe This is the least confrontational step, used to prompt the individual to reconsider their actions or decisions gently. It is often phrased as a question to encourage discussion and reflection. Example: “Do you know that the patient’s blood pressure has dropped significantly?”

|

|

|

Alert If the initial probe does not lead to a resolution, the next step is to alert the team by suggesting a reassessment. This step signals concern without directly opposing the action. Example: “Can we re-assess the medication dose before proceeding?”

|

|

|

Challenge A more direct challenge is required if the concern remains unaddressed. This step explicitly asks the person to stop their action to ensure safety. Example: “Please stop what you are doing while we double-check the patient’s identity before administering the medication.”

|

|

|

Emergency The final and most assertive step is used in critical situations where immediate action is necessary to prevent harm. It is a direct command that prioritises patient safety above all else. Example: “STOP what you are doing! That is the wrong medication!”

|

Closed Loop Communication

Closed loop communication is a communication technique designed to ensure clarity, prevent errors, and verify understanding, especially in high-stress or high-risk environments like healthcare. Research has shown that using closed-loop communication during a crisis can significantly reduce the time-to-task completion and decrease adverse events (Diaz & Dawson, 2020; Doorey et al., 2020; El-Shafy et al., 2017; Yemada et al., 2016). This process involves multiple steps to confirm that the message has been correctly received, interpreted, and acted upon.

|

Sender communicates a message Example: “John, give 1mg adrenaline IV followed by a 20 mL normal saline flush.”

|

|

Receiver interprets the message, acknowledges receipt, and communicates it back to the sender Example: “OK Mike, I am going to give 1mg adrenaline IV followed by a 20 mL normal saline flush.”

|

|

Sender confirms that the intended message is received Example: “That’s correct, John.”

|

|

Receiver reports back when the message has been acted upon Example: “Mike, 1mg adrenaline IV with a 20 mL normal saline flush has been given.”

|

Documentation

Effective documentation is a critical aspect of communication in healthcare, ensuring that accurate, relevant, and up-to-date information about a patient’s care is readily accessible to support safe and high-quality clinical decisions (ACSQHC, 2024a).

According to the ACSQHC (2024a), effective documentation should meet several key standards:

In addition to these core principles, documentation should include critical elements such as:

- Assessments: Details about the patient’s condition at the time of each assessment, including physical examinations, laboratory results, and diagnostic findings.

- Actions taken: Clear records of interventions or treatments administered, such as medications, procedures, and care provided.

- Outcomes: Information on the effectiveness of treatments, including patient responses, improvements, or any setbacks.

- Changes: Any significant changes in the patient’s condition, treatment plan, or response to care.

- Follow-up processes: Plans for ongoing care, referrals, or follow-ups, ensuring continuity in the patient’s treatment.

Finally, healthcare documentation must adhere to medico-legal standards, ensuring that records are accurate, complete, and maintained in a manner that ensures quick access to accurate documentation to drive decisions in a crisis. Healthcare documentation protects both the patient’s privacy and the healthcare provider’s legal responsibilities. Proper documentation is not only essential for patient care but also serves as a legal record of the actions taken, which may be referenced in case of disputes, audits, or regulatory investigations (ACSQHC, 2024a).

Respond

|

Respond refers to the timely and appropriate actions taken to address patient deterioration once recognised. A rapid and coordinated response is crucial in preventing complications from escalating to a life-threatening state. Equipping healthcare providers with the skills and confidence to act decisively can mean the difference between recovery and preventable loss of life. Patient deterioration requiring immediate attention fall into two categories: physiological and psychological.

|

Acute Physiological Deterioration

An acute physiological deterioration occurs when a patient’s vital functions are compromised, posing a threat to life or health. In these situations, nurses must respond swiftly and decisively to stabilise the patient and prevent further deterioration. Utilising primary and secondary survey mnemonics helps ensure a structured and focused approach to assessment and intervention.

Primary Survey: ABCDE Assessment

The primary survey, or ABCDE assessment, is a structured, systematic approach used in healthcare settings to assess and manage patients. The goal is to swiftly identify and address immediate threats to the patient’s life or health, initiating appropriate interventions to optimise outcomes and promote patient survival. This type of assessment is rapid and focused and aims to identify and address critical health issues promptly. It prioritises immediate life-threatening conditions and ensures timely intervention. This method is particularly useful in an emergency where quick decision-making is essential.

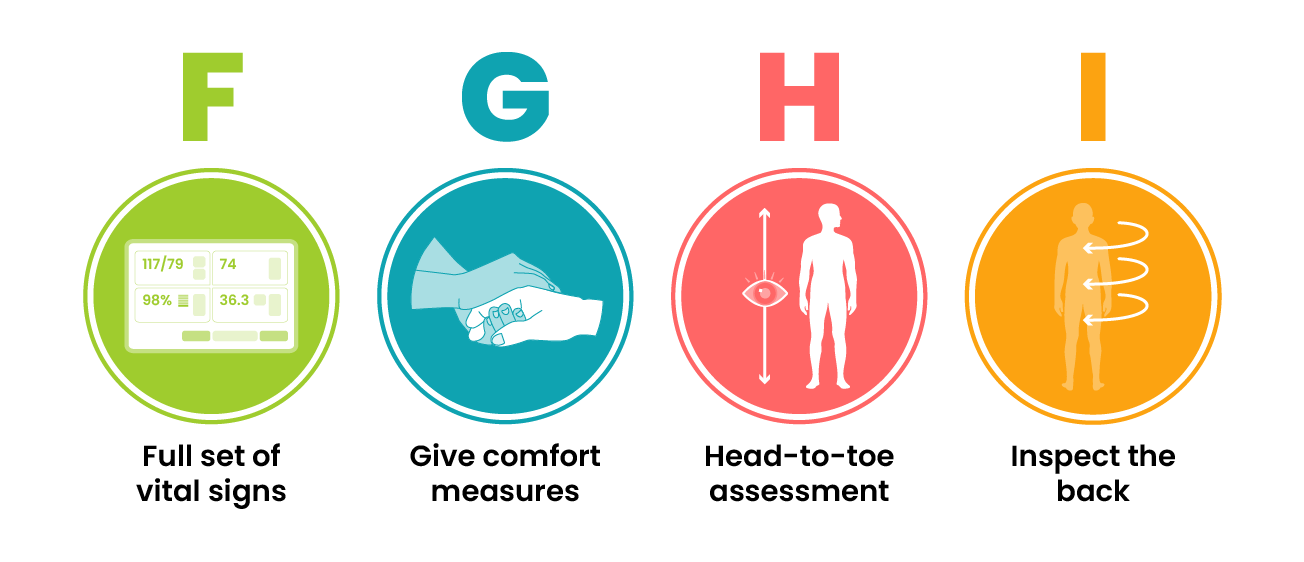

Secondary Survey: FGHI Assessment

After completing the primary survey and implementing necessary interventions, the secondary survey (FGHI assessment) is conducted to obtain a more detailed assessment of the patient’s condition and medical history and refine treatment strategies.

|

Full set of vital signs and further investigations (F) A comprehensive set of vital signs is recorded, including blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate, temperature, and oxygen saturation. Further investigations such as arterial blood gas (ABG) analysis, chest X-rays, ECGs, and laboratory tests may be conducted to guide further treatment.

|

|

Give comfort measures (G)

Pain assessment and management are prioritised. This includes both pharmacological (analgesics, sedatives) and non-pharmacological (repositioning, reassurance) interventions. Emotional and psychological support for the patient and their family is also considered.

|

| History and head-to-toe assessment (H)

A detailed history is obtained using the SAMPLE method (Signs/Symptoms, Allergies, Medications, Past medical history, Last meal, Events leading to the illness/injury). A systematic head-to-toe physical examination follows, identifying any additional injuries, abnormalities, or ongoing concerns.

|

|

|

Inspect the back (I)

The final step involves inspecting the patient’s back, often by log-rolling them carefully to check for hidden injuries, pressure injury, or other complications. This is particularly important in trauma cases where spinal injuries or unnoticed wounds can be life-threatening.

|

The goal during an acute physiological deterioration is to stabilise the patient’s condition, restore physiological function, and initiate appropriate interventions to prevent further harm. During a physiological crisis, nurses must communicate clearly with other healthcare team members and prioritise interventions based on the patient’s condition and available resources. Multidisciplinary collaboration is crucial for timely and effective care.

Acute Psychological Deterioration

Mental health nursing is a specialised field, and nurses are not expected to be experts in managing psychological crises without proper training. However, psychological crises can occur in any healthcare environment, and recognising the early signs of acute psychological deterioration is crucial in ensuring timely escalation of care to specialised mental health professionals, which can significantly improve patient outcomes.

An acute psychological deterioration refers to a state of acute emotional or mental distress that significantly impairs an individual’s ability to cope with their current circumstances. Recognising deterioration in a person’s mental state relies on identifying noticeable changes in their behaviour, cognitive abilities, perception or emotional well-being (ACSQHC, 2017).

Acute psychological deterioration may arise due to various factors such as trauma, acute stress, psychiatric disorders, substance abuse, or suicidal ideation. In such cases, the primary assessment evaluates the patient’s mental status, ensures their safety, and identifies immediate psychological needs. Key components include assessing the patient’s level of consciousness, cognition, thought processes, mood, and affect. While structured tools do not replace the need for clinical judgement, the use of screening tools can assist in assessing a person’s mental state (ACSQHC, 2017).

The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) is a brief cognitive screening tool used to assess orientation, memory, attention, language, and visuospatial skills. Click on each section to learn more about each assessment component in the MMSE:

While useful for detecting dementia or delirium, the MMSE is not a diagnostic tool and may be influenced by education, language, and cultural factors.

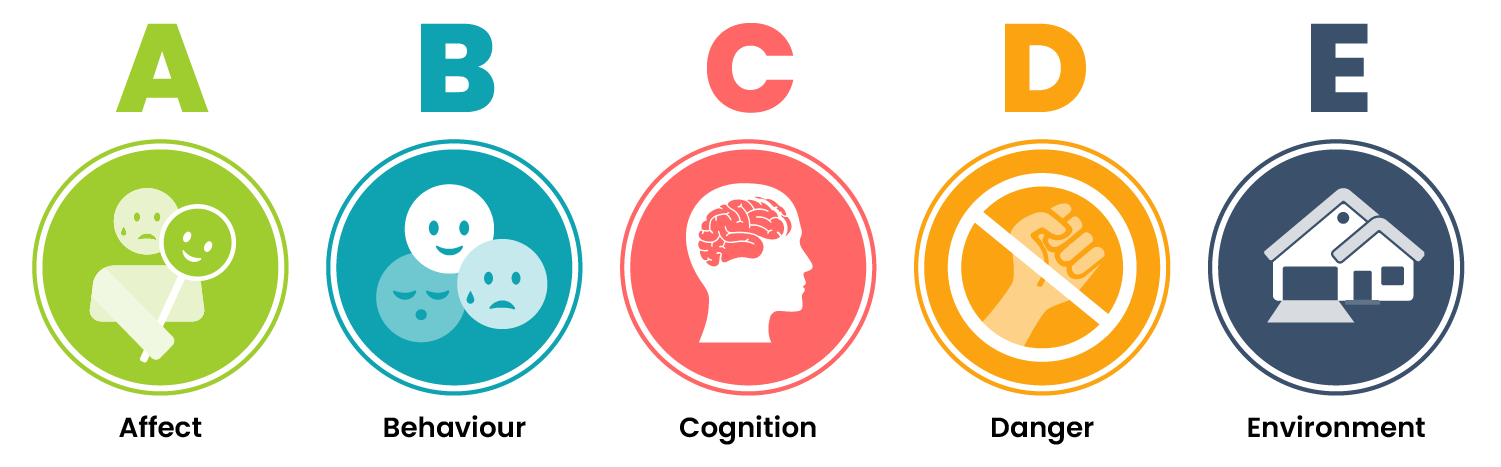

Another structured approach to assessing psychological state is the ABCDE assessment, but from a mental health perspective. This quick assessment provides a straightforward framework for mental health assessment during an acute crisis:

|

Affect Assess the patient’s emotional expression and mood. Does it match their stated mood? Is it appropriate for the situation? |

|

Behaviour Evaluate the patient’s actions. Are they agitated, calm, withdrawn, or erratic? Is there a risk to themselves or others? |

|

|

Cognition Assess orientation, memory, and attention. Check if the patient is confused, disoriented, or experiencing hallucinations or delusions. |

|

Danger to self or others This is the critical component, determining the patient’s risk of self-harm or harm to others. |

|

Environment Ensure the environment is safe for both the patient and the staff. This includes removing harmful objects and securing a calm space. |

When encountering a psychological crisis, nurses must employ compassionate and effective assessment techniques to ensure the safety and well-being of the patient. Nurses utilise active listening skills to allow patients to express their feelings and concerns openly. To ensure a safe environment, the nurse may need to implement measures like constant observation if the patient poses a risk to themselves or others. Recommending a referral to mental health specialists and initiating crisis intervention protocols are often part of the response in such situations.

Basic Life Support

When patients deteriorate to the point of cardiopulmonary arrest, immediate intervention is critical. Basic Life Support (BLS) provides the foundation for sustaining life until advanced life support (ALS) can be administered. Recognising the signs of cardiac arrest early and responding swiftly with BLS techniques can significantly improve the chances of survival, making it an essential skill for nurses in any setting.

While the principles of BLS, including early recognition of arrest, effective chest compressions, and timely defibrillation, remain consistent across both adult and paediatric basic life support, the specific techniques and considerations for adult and paediatric patients differ to ensure the best possible outcome for each. Understanding these distinctions is crucial for providing effective care during a cardiac arrest situation.

Adult Basic Life Support

The mnemonic DRsABCD is used to easily recall the steps required. Click on each step below to revise the step-by-step BLS process for adults.

Link to Learning

Follow the link to access the ANZCOR adult basic life support guidelines.

Paediatric Basic Life Support

ANZCOR suggests that health professionals working in healthcare settings where they are responsible for the care of infants and children should be trained in Paediatric BLS (PBLS). Lay persons and other health professionals should be trained in general BLS (ANZCOR, 2021b). While the mnemonic DRsABCD still guides the basic life support (BLS) process, in PBLS, several key modifications are made. By modifying certain aspects of the BLS process, PBLS addresses the unique physiological needs of children and maximises the likelihood of a successful outcome. The following modifications are made during PBLS:

- Opening the airway: Because a child’s airway differs anatomically from an adult’s, using a neutral position for infants or a sniffing position for older children is essential. Overextending the head can obstruct the airway rather than open it.

- Delivering two rescue breaths before starting chest compressions: This adjustment ensures increased oxygen delivery, addressing the primary cause of cardiac arrest in children—hypoxia.

- Compression-to-ventilation ratio: In paediatric CPR, the compression-to-ventilation ratio is also modified to 15 compressions followed by 2 breaths. It is important to provide more frequent rescue breaths in PBLS because hypoxia (a lack of oxygen) is the most common cause of cardiac arrest in children. Unlike adults, where cardiac arrest is often caused by underlying heart conditions, paediatric cardiac arrests are typically respiratory in origin.

- Compressions: The two-finger or two-thumb method is used for babies and the one-hand method or the normal two-hand method for children, depending on the size of the child and the rescuer. The depth of compressions will be about 4cm for an infant and 5cm for an older child.

Let’s take a closer look at the DRsABCD algorithm for paediatric patients.

Link to Learning

Follow the link to access the ANZCOR Paediatric Basic Life Support (PBLS) for health professionals guidelines.

Post-Resuscitation Care

Once the patient has return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) and has been stabilised, it is essential to provide comprehensive post-resuscitation care. This includes performing a structured ABCDE assessment and closely monitoring vital signs.

Following a cardiac arrest, the healthcare team will typically initiate diagnostic investigations to identify and treat the underlying cause. These may include blood tests, arterial blood gas (ABG) analysis, chest X-rays, and other relevant investigations or procedures.

In a ward setting, patients recovering from cardiac arrest often require transfer to high-acuity areas, such as an intensive care unit (ICU) or a tertiary facility with advanced monitoring and treatment capabilities. Preparing the patient for transfer, documenting the events and preparing for handover of care will be important.

Effective communication during the handover of care is critical. Utilising the ISBAR (Introduction, Situation, Background, Assessment, Recommendation) framework facilitates a clear and structured exchange of information, supporting continuity of care and improving patient outcomes.

When to Stop CPR

|

The rescuer should continue performing CPR until one of the following situations occurs (ANZCOR, 2021a):

|

Importance of Continuous Training and Practice

Continuous training and practice are essential for maintaining proficiency in BLS. Regular training sessions, simulation exercises, and refresher courses help ensure that healthcare providers are prepared to respond effectively in emergency situations. Staying updated with the latest guidelines and protocols from organisations such as the Australian and New Zealand Committee on Resuscitation (ANZCOR) is crucial.

Link to Learning

Follow the link to access numerous ANZCOR educational resources and guidelines available on first-aid management, basic life support and advanced life support.

Acute Resuscitation Plans

A key challenge in managing deteriorating patients is establishing appropriate care goals and determining the limitations of medical treatment (Jones, 2023). An Acute Resuscitation Plan (ARP) is a medical order documenting a patient’s wishes regarding resuscitation and life-sustaining measures in the event of a critical situation, essentially outlining what treatments should be provided or withheld if their health rapidly declines (Queensland Health, 2020). The form is authorised by the most senior medical practitioner available and contains important information regarding:

- The patient’s current health condition

- Medically appropriate resuscitation plans in the event of an emergency

- Recommended treatments and available options

- Substitute decision-maker(s) in the event the patient is unable to make healthcare decisions

- Patient preferences concerning life-sustaining measures, including the appropriateness of administering cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).

Changing Course: End-of-Life Care

The ACSQHC (2023) has recognised that care of the deteriorating patient may not always be appropriate because they are at the end of their lives.

While ARPs can assist in the decision to go down the end-of-life care pathway, advocating for the patient and knowing what to do to care for the patient with life-limiting illness can be challenging. Having a basic understanding of the principles of end-of-life care can assist with caring for the deteriorating patient on an end-of-life care pathway. We will only briefly touch on this topic in this chapter as there is a chapter dedicated to end-of-life care later in this book.

Link to Learning

To help support quality end-of-life care, the ACSQHC has developed the following resources. Click on the links below to access and explore these resources:

- The Comprehensive Care Standard from the NSQHS standards(2nd ed.), which includes comprehensive care at end-of-life

- National Consensus Statement: Essential elements for safe and high-quality end-of-life care

- National Consensus Statement: Essential elements for safe and high-quality paediatric end-of-life care

- End-of-Life Care Audit Toolkit.

According to the National Consensus Statement, end of life is defined as “The period when a person is living with, and impaired by, a fatal condition, even if the trajectory is ambiguous or unknown” (ACSQHC, 2023, p. 27). The national consensus statement outlines 10 crucial elements for delivering safe, high-quality end-of-life care. Essential elements 1–5 describe how end-of-life care should be approached and these essential elements include: Recognising end-of-life, patient-centred communication and shared decision-making, multidisciplinary collaboration and coordination of care, providing comprehensive care and responding to concerns (ACSQHC, 2023). Included in this document are important considerations and recommendations for caring for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples at end of life. For more information on these considerations, access the National Consensus Statement: Essential elements for safe and high-quality end-of-life care via the link above.

Management at End-of-Life Care

Although a patient may be on an end-of-life care pathway, they are still included in being recognised for deterioration, especially in the areas of pain and symptom management. End of life is associated with physical manifestations of discomfort, and can include symptoms such as dyspnoea, nausea and vomiting, cough, seizures, pain, and delirium. The focus of care shifts from curative or resuscitative efforts to ensuring comfort and dignity by managing distressing symptoms.

End-of-life deterioration often presents with physical manifestations of discomfort, including:

By managing the pain and symptoms of end-of-life deterioration, the patient and their family can be supported to experience a dignified death of their loved one.

Key Takeaways

In this chapter, we covered:

- Early recognition and timely interventions can significantly improve patient outcomes, reduce length of stay, and prevent adverse events.

- The 3Ps and 3Rs: predict, prepare, prevent, recognise, relay and respond are strategies that can prevent a failure to recognise and respond to acute deterioration.

- Predict: By analysing patterns and trends in vital signs, laboratory results, and other data, clinicians can identify patients at risk of deterioration before it occurs.

- Prepare: Preparation involves ensuring that you have the necessary resources, training, and systems to identify and respond effectively to patient deterioration. This can be done through pre-emptive safety checks of the patient, environment and resources, and participating in training.

- Prevent: Prevention involves carefully implementing measures to prevent further deterioration and significantly reduce the risk of adverse outcomes in deteriorating patients. This can be done by utilising Early Warning Scores (EWS), algorithms, protocols and pathways, escalation protocols and rapid response systems.

- Recognise: Recognition involves identifying early signs of patient deterioration through vigilant vital signs monitoring and assessments, and understanding the key physiological indicators and clinical symptoms that can signal a patient’s deterioration.

- Relay: Effective communication or “relaying” information ensures that critical information about a patient’s condition is accurately and promptly shared among healthcare team members and escalated in a timely manner. Tools and strategies like ISBAR, PACE and closed-loop communication can enhance the effectiveness of this communication.

- Respond: Respond refers to the timely and appropriate actions taken to address patient deterioration once recognised. A rapid and coordinated response is crucial in preventing complications from escalating to a life-threatening state.

- Patient deterioration requiring immediate attention falls into two categories: physiological and psychological.

- Acute physiological deterioration occurs when a patient’s vital functions are compromised, posing a threat to life or health. Primary (ABCDE) and secondary (FGHI) surveys with appropriate interventions at each stage should be performed to swiftly assess, stabilise, and prevent further deterioration.

- Acute psychological deterioration refers to a state of acute emotional or mental distress that significantly impairs an individual’s ability to cope with their current circumstances and can occur due to various reasons including trauma, acute stress, psychiatric disorders, substance abuse, or suicidal ideation. The primary goal in this situation is to evaluate the patient’s mental status, ensure their safety, and identify immediate psychological needs.

- Basic life support (BLS) may need to be performed if the deteriorating patient goes into cardiac arrest. BLS is performed using the Danger, Response, send for Help, Airway, Breathing, Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Defibrillator (DRsABCD) algorithm.

- While the principles of BLS, including early recognition of arrest, effective chest compressions, and timely defibrillation, remain consistent across both adult and paediatric basic life support, the specific techniques and considerations for adult and paediatric patients differ to ensure the best possible outcome for each.

- An Acute Resuscitation Plan (ARP) is a medical order documenting a patient’s wishes regarding resuscitation and life-sustaining measures in the event of a critical situation, essentially outlining what treatments should be provided or withheld if their health rapidly declines.

- When caring for the deteriorating patient, the decision may be made to go down the end-of-life pathway where the focus of care shifts from curative or resuscitative efforts to ensuring comfort and dignity by managing distressing symptoms.

References

Anstey, M. H., Bhasale, A., Dunbar, N. J., & Buchan, H. (2019). Recognising and responding to deteriorating patients: What difference do national standards make? BMC Health Services Research, 19(1), Article 639. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4339-z

Ashbeck, R., Stellpflug, C., Ihrke, E., Marsh, S., Fraune, M., Brummel, A., & Holst, C. (2021). Development of a standardized system to detect and treat early patient deterioration. Journal of Nursing Care Quality, 36(1), 32-37. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCQ.0000000000000484

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2023, October 10). Causes of death, Australia (No. 3303.0). https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/causes-death/causes-death-australia/latest-release

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. (2017, July). National consensus statement: Essential elements for recognising and responding to deterioration in a person’s mental state. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/sites/default/files/2019-06/national-consensus-statement-essential-elements-for-recognising-and-responding-to-deterioration-in-a-persons-mental-state-july-2017.pdf

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. (2021, November). National consensus statement: Essential elements for recognising and responding to acute physiological deterioration (3rd ed.). https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/sites/default/files/2021-12/essential_elements_for_recognising_and_responding_to_acute_physiological_deterioration.pdf

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. (2023). Essential elements for safe and high-quality end-of-life care: National consensus statement. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-12/national_consensus_statement_-_essential_elements_for_safe_and_high-quality_end-of-life_care.pdf

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. (2024a). Documentation of information. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/standards/nsqhs-standards/communicating-safety-standard/documentation-information

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. (2024b). Recognising and responding to acute deterioration standard. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/standards/nsqhs-standards/recognising-and-responding-acute-deterioration-standard

Australian and New Zealand Committee on Resuscitation. (2021a). Guideline 12.1 – Paediatric Basic Life Support (PBLS) for health professionals. https://www.anzcor.org/assets/anzcor-guidelines/guideline-12-1-paediatric-basic-life-support-pbls-for-health-professionals-254.pdf

Australian and New Zealand Committee on Resuscitation. (2021b). Guideline 8 – Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation. https://www.anzcor.org/home/basic-life-support/guideline-8-cardiopulmonary-resuscitation-cpr/

Burgess, A., van Diggele, C., Roberts, C., & Mellis, C. (2020). Teaching clinical handover with ISBAR. BMC Medical Education, 20(Suppl 2). Article 459. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02285-0

Burke, J. R., Downey, C., & Almoudaris, A. M. (2022). Failure to rescue deteriorating patients: A systematic review of root causes and improvement strategies. Journal of Patient Safety, 18(1), e140–e155. https://doi.org/10.1097/PTS.0000000000000720

Chua, W. L., Legido-Quigley, H., Ng, P. Y., McKenna, L., Hassan, N. B., & Liaw, S. Y. (2019). Seeing the whole picture in enrolled and registered nurses’ experiences in recognizing clinical deterioration in general ward patients: A qualitative study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 95, 56–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.04.012

Clinical Excellence Commission. (n.d.). Between the flags. NSW Government. https://www.cec.health.nsw.gov.au/keep-patients-safe/between-the-flags

Considine, J., Casey, P., Omonaiye, O., van Gulik, N., Allen, J., & Currey, J. (2024). Importance of specific vital signs in nurses’ recognition and response to deteriorating patients: A scoping review. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 33(7), 2544–2561. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.17099

Considine, J., & Currey, J. (2015). Ensuring a proactive, evidence-based, patient safety approach to patient assessment. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 24(1–2), 300–307. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12641

Della Ratta, C. (2016). Challenging graduate nurses’ transition: Care of the deteriorating patient. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 25(19–20), 3036–3048. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.13358

Diaz, M. C. G., & Dawson, K. (2020). Impact of simulation-based closed-loop communication training on medical errors in a pediatric emergency department. American Journal of Medical Quality, 35(6), 474–478. https://doi.org/10.1177/1062860620912480

Doorey, A. J., Turi, Z. G., Lazzara, E. H., Mendoza, E. G., Garratt, K. N., & Weintraub, W. S. (2020). Safety gaps in medical team communication: Results of quality improvement efforts in a cardiac catheterization laboratory. Catheterization and Cardiovascular Interventions, 95(1), 136–144. https://doi.org/10.1002/ccd.28298

Duff, B., El Haddad, M., & Gooch, R. (2020). Evaluation of nurses’ experiences of a post education program promoting recognition and response to patient deterioration: Phase 2, clinical coach support in practice. Nurse Education in Practice, 46. Article 102835. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2020.102835

El-Shafy, I. A., Delgado, J., Akerman, M., Bullaro, F., Christopherson, N. A. M., & Prince, J. M. (2018). Closed-loop communication improves task completion in pediatric trauma resuscitation. Journal of Surgical Education, 75(1), 58–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2017.06.025

Goldsworthy, S., Muir, N., Baron, S., Button, D., Goodhand, K., Hunter, S., McNeill, L., Perez, G., McParland, T., Fasken, L., & Peachey, L. (2022). The impact of virtual simulation on the recognition and response to the rapidly deteriorating patient among undergraduate nursing students. Nurse Education Today, 110. Article 105264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2021.105264

Hodgetts, T. J., Kenward, G., Vlackonikolis, I., Payne, S., Castle, N., Crouch, R., Ineson, N., & Shaikh, L. (2002). Incidence, location and reasons for avoidable in-hospital cardiac arrest in a district general hospital. Resuscitation, 54(2), 115–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0300-9572(02)00098-9

Jones, D. (2023). Deteriorating patients in Australian hospitals: Current issues and future opportunities. Australian Critical Care, 36(6), 928–930. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aucc.2023.07.004

Le Lagadec, M. D., & Dwyer, T. (2017). Scoping review: The use of early warning systems for the identification of in-hospital patients at risk of deterioration. Australian Critical Care, 30(4), 211–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aucc.2016.10.003

Manojlovich, M., & Krein, S. L. (2022). We don’t talk about communication: Why technology alone cannot save clinically deteriorating patients. BMJ Quality & Safety, 31(10), 698–700. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2022-014798

Massey, D., Chaboyer, W., & Anderson, V. (2017). What factors influence ward nurses’ recognition of and response to patient deterioration? An integrative review of the literature. Nursing Open, 4(1), 6–23. https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.53

McQuillan, P., Pilkington, S., Allan, A., Taylor, B., Short, A., Morgan, G., Nielsen, M., Barrett, D., & Smith, G. (1998). Confidential inquiry into quality of care before admission to intensive care. BMJ, 316, 1853–1858. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.316.7148.1853

Newman, D., Hofstee, F., Bowen, K., Massey, D., Penman, O., & Aggar, C. (2023). A qualitative study exploring clinicians’ attitudes toward responding to and escalating care of deteriorating patients. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 37(4), 541–548. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2022.2104231

Padilla, R. M., & Mayo, A. M. (2018). Clinical deterioration: A concept analysis. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 27(7–8), 1360–1368. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14238

Park, S. A. & Kellerman, T. (2022, April 14). Acute nursing care: Recognition and response to deteriorating patients. Australian Nursing & Midwifery Journal. https://anmj.org.au/acute-nursing-care-recognition-and-response-to-deteriorating-patients/

Queensland Government. (2024). Ryan’s Rule. https://www.qld.gov.au/health/support/shared-decision-making/ryans-rule

Queensland Health. (2020, April). Acute resuscitation plan: Queensland Health clinical guidelines. Queensland Government. https://clinicalexcellence.qld.gov.au/sites/default/files/docs/resourses/arp/arp-clinical-guidelines.pdf

Warren, T., Moore, L. C., Roberts, S., & Darby, L. (2021). Impact of a modified early warning score on nurses’ recognition and response to clinical deterioration. Journal of Nursing Management, 29(5), 1141-1148. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.13252

Yamada, N. K., Fuerch, J. H., & Halamek, L. P. (2016). Impact of standardized communication techniques on errors during simulated neonatal resuscitation. American Journal of Perinatology, 33(4), 385-392. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0035-1565997

Chapter Attribution

This chapter has been adapted in parts from:

Fundamentals of nursing (2024) edited by Christy Bowen, Lindsay Draper and Heather Moore, OpenStax, is used under a CC BY licence.

Nursing care at the end of life (2015) by Susan E. Lowey, Open SUNY Textbooks, is used under a CC BY-NC-SA licence.

Media Attributions

- Effective Intervention © Eileen Siddins is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- The 3Ps and 3Rs © Eileen Siddins is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Mews Chart © Clinical Excellence Queensland is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- The PACE Communication Tool © Eileen Siddins is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- FGHI Assessment © Eileen Siddins is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- ABCDE Mental Health © Eileen Siddins is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Caring Hands © Ben Green is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

A patient whose clinical condition is worsening, increasing their risk of serious adverse outcomes such as cardiac arrest, organ failure, or death

A healthcare system designed to quickly identify and respond to patients whose condition is deteriorating rapidly, aiming to intervene early and prevent further complications or critical situations by activating a dedicated team of healthcare professionals when specific clinical criteria are met

The complete loss of heart function, leading to an absence of blood circulation and oxygen delivery to vital organs

A clinical tool used in healthcare to identify patients at risk of deterioration

A dedicated team of healthcare professionals often consisting of both Doctors and Nurses with advanced life support skills who respond to patient deterioration when escalated

A specialised group of healthcare professionals, with advanced life support skills, trained to respond rapidly to deteriorating patients in a hospital setting

A step-by-step procedure designed to guide healthcare providers through clinical decision-making processes for certain conditions or diagnoses

A management tool used in healthcare to standardise and optimise patient care processes specific to certain conditions

A predefined set of procedures used to manage and respond to situations where a patient's condition is deteriorating

Number of breaths per minute (bpm). Normal is 12-20 bpm

A blood test taken from an artery that primarily measures the levels of oxygen and carbon dioxide and pH balance (acidity and alkalinity) and lactate in your blood

(Electrocardiogram): a medical test that records the electrical activity of the heart

A mnemonic utilised during a secondary survey to guide a thorough patient assessment and stands for Symptoms, Allergies, Medications, Past medical history, Last meal, and Events leading up to illness or injury

A technique used to move a patient while maintaining the alignment of their spine

Skin breakdown caused when a patient’s skin and soft tissue press against a hard surface for a prolonged period of time, causing reduced blood supply and resulting in damaged tissue

A set of medical interventions used to manage life-threatening emergencies, particularly cardiac arrest, severe respiratory distress, and shock. ALS builds upon Basic Life Support (BLS) by incorporating advanced airway management, drug administration, and cardiac monitoring.

An algorithm used in Basic Life Support (BLS) representing the steps of BLS: Danger, Response, send for help, Airway, Breathing, Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR) and Defibrillation.

The period when a person is living with, and impaired by, a fatal condition, even if the trajectory is ambiguous or unknown