1.4 Smoking Cessation

Introduction to Smoking Cessation

|

|

|

🎞️ Video 1: Introduction to Smoking Cessation ⏲️3:19 mins

Tobacco is the main component of cigarettes and nicotine is the main chemical in tobacco. Nicotine is toxic, highly addictive and a stimulant. When a person inhales smoke from a cigarette, nicotine is distilled from the tobacco, carried to the lungs and absorbed into the pulmonary venous circulation. It then enters arterial circulation and moves quickly to the brain (nicotine reaches the brain within 10 to 20 seconds of inhaling smoke) and diffuses into the brain tissue. Nicotine binds to nicotinic cholinergic receptors which are ligand gated ion channels. When an agonist like nicotine binds to the outside of the channel, the channel opens allowing for the entry of cations like sodium and calcium.

The stimulation of central nicotinic receptors by nicotine results in the release of a variety of neurotransmitters, most notably dopamine. This leads to a drug induced reward. The dopamine release leads to a pleasurable experience which is critical to the reinforcing effects of nicotine. Drug dependence normally comprises of both physical and a psychological dependence. Watch the following YouTube video from Quitline for a short example of how nicotine promotes dependence by activating the dopaminergic system, the reward system in the brain:

But it’s not just nicotine in the tobacco cigarettes that is harmful. Australian cigarettes also contain other ‘additives’ which often contribute to the toxicity, addictiveness and attractiveness of tobacco products. And many new chemicals are formed when components of cigarettes (the tobacco, the chemicals added to it and the paper wrapper) undergo chemical reactions during burning. Over 7,000 different chemicals can be detected in the emissions of combusted tobacco products such as cigarettes. Some of these include tar-based products which have carcinogenic properties, carbon monoxide which reduces the oxygen carrying capacity of red blood cells, hydrogen cyanide, ammonia and toxic metals.

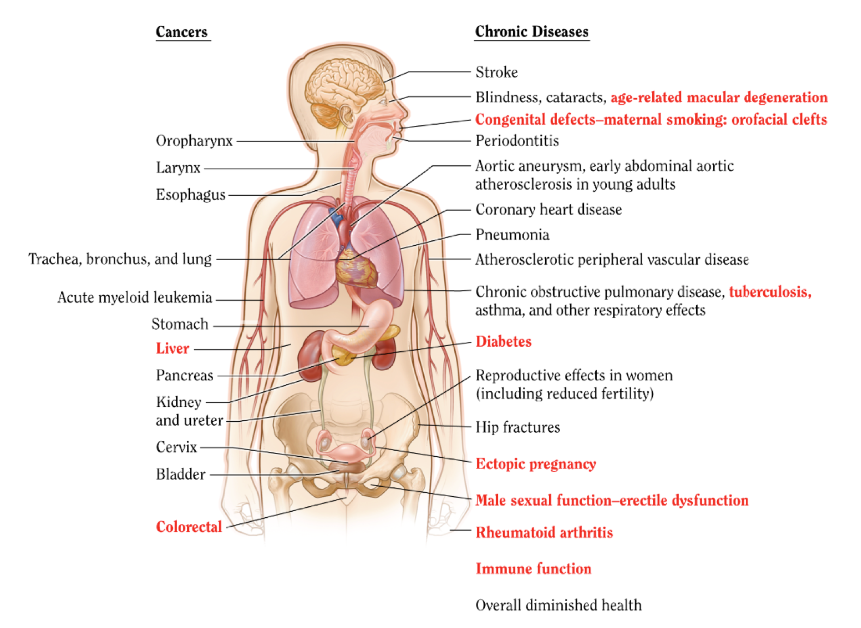

Cigarette smoking is the leading cause of preventable disease and death in Australia. It contributes to cardiovascular disease, cancer, lung disease, diabetes, dental problems, hearing loss, vision loss, fertility problems, osteoporosis and mental health issues. In 2018, smoking was associated with 20,500 deaths (13% of all deaths) and was responsible for 8.6% of the total burden of disease in Australia. Second-hand smoke is also serious health threat. Non-smokers who live with a smoker have a 25-30% greater risk of developing heart disease and a 20-30% increased risk of developing lung cancer. Exposure to environmental tobacco smoke is especially harmful to a developing fetus, babies and children. In 2022, 12.2% of Australian adults were reported to be current smokers and the smoking rate for men was higher than their female counterparts. People who lived in the areas of most socioeconomic disadvantage were the most likely to smoke daily, with 13.4% doing so in 2022–2023. In general, areas with higher socioeconomic advantage had lower proportions of people smoking daily, with the lowest level of smoking prevalence (4.1%) occurring in the areas of most socioeconomic advantage. People living in remote and very remote areas were 2.9 times as likely to smoke daily (20%) as people living in major cities (7.0%). Furthermore, 1 in 5 First Nations people smoked daily in 2022–2023, and after adjusting for differences in age, First Nations people were 2.6 times as likely as non‑Indigenous people to smoke daily in 2022–2023.

In 2022, 12.2% of Australian adults were reported to be current smokers and the smoking rate for men was higher than their female counterparts. People who lived in the areas of most socioeconomic disadvantage were the most likely to smoke daily, with 13.4% doing so in 2022–2023. In general, areas with higher socioeconomic advantage had lower proportions of people smoking daily, with the lowest level of smoking prevalence (4.1%) occurring in the areas of most socioeconomic advantage. People living in remote and very remote areas were 2.9 times as likely to smoke daily (20%) as people living in major cities (7.0%). Furthermore, 1 in 5 First Nations people smoked daily in 2022–2023, and after adjusting for differences in age, First Nations people were 2.6 times as likely as non‑Indigenous people to smoke daily in 2022–2023.

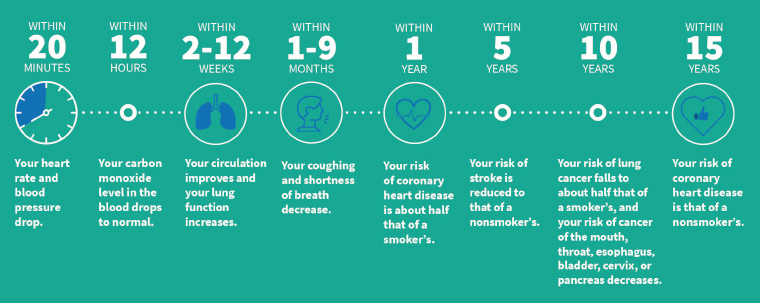

There is strong evidence that any advice from a healthcare professional is effective in encouraging smoking cessation. Healthcare professionals can encourage those who smoke to quit with minimal (<3 minutes) intervention. It has been shown that 1 in every 33 such conversations will lead to a patient successfully quitting smoking. By advocating and assisting in smoking cessation, pharmacists can reduce patients’ risk of premature death, smoking-related disease, financial burden and contribution to environmental tobacco smoke. The image below shows the immediate and long term health benefits to an individual who ceases to smoke cigarettes.

In this module you will learn how community pharmacists can support smoking cessation. You will reinforce your knowledge of motivational interviewing to assess patients’ readiness to quit and tailor information to the individual’s stage of change. You will also learn how to assist patients and advise on behavioural modification. Furthermore, you will learn about the efficacy, safety profile, regimens, practice points and counselling points of Nicotine Replacement Therapy (NRT) and other pharmacotherapy to support smoking cessation. Lastly, you will learn about e-cigarettes, or vapes, and what pharmacists need to know in relation to vapes for smoking cessation or the management of nicotine dependence.

In this module you will learn how community pharmacists can support smoking cessation. You will reinforce your knowledge of motivational interviewing to assess patients’ readiness to quit and tailor information to the individual’s stage of change. You will also learn how to assist patients and advise on behavioural modification. Furthermore, you will learn about the efficacy, safety profile, regimens, practice points and counselling points of Nicotine Replacement Therapy (NRT) and other pharmacotherapy to support smoking cessation. Lastly, you will learn about e-cigarettes, or vapes, and what pharmacists need to know in relation to vapes for smoking cessation or the management of nicotine dependence.

We are going to explore the following topics regarding smoking cessation:

- Motivational Interviewing

- Behavioural Modification

- Nicotine Replacement Therapy

- Other Pharmacotherapy for Smoking Cessation

- E-cigarettes and Vaping for Smoking Cessation and Nicotine Dependence.

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this module, you should be able to:

- Understand the pathophysiology of nicotine dependence and health implications of cigarette smoking and passive smoking.

- Demonstrate and apply knowledge of motivational interviewing techniques related to smoking cessation.

- Demonstrate and apply knowledge of behavioural modification to aid in smoking cessation.

- Understand and apply knowledge of the efficacy, safety profile, drug regimes, practice and counselling points of nicotine replacement therapy and other pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation.

Motivational Interviewing

|

|

|

🎞️ Video 2: Motivational Interviewing for Smoking Cessation ⏲️4:36 mins

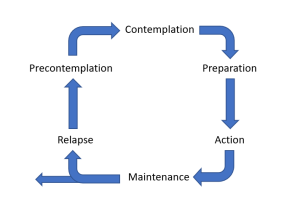

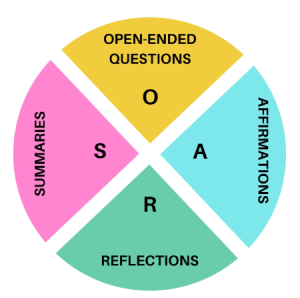

Motivational interviewing is an evidence-based counselling technique and an effective way to talk to patients about change. Through motivational interviewing, pharmacists can acknowledge and explore a patient’s ambivalence about their smoking behaviour. It also allows patients who smoke to clarify what goals are important to them and organise their reasons in a way that supports action. Pharmacists should utilize OARS (open-ended questions, affirmations, reflections and summaries), the 5A’s (ask, advise, assess, assist and arrange) and the Transtheoretical Model (pre-contemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, maintenance and lapse/relapse) when using motivational interviewing to support smoking cessation.

📺 The following clip gives an idea as to how we talk to our patients trying to quit smoking, and how we motivate use both the 5A’s and transtheoretical model within that process.

If you want to learn more, have a look at an excellent article on motivational interviewing techniques written by Dan Lubman, Kate Hall and Tania Gibbie in 2012. (Lubman, d., Hall, K., and Biggie, T. 2012. Motivational interviewing techniques. Facilitating behaviour change in the general practice setting. Volume 41: Issue 9. 2012. Available at [RACGP – Motivational interviewing techniques – facilitating behaviour change in the general practice setting].

Futhermore, AFP-Sep-2012-Motivational-interviewing-techniques can be accessed here.

Behavioural Modification

|

|

|

🎞️ Video 3: Behavioural Modification for Smoking Cessation ⏲️2:38 mins

The strongest evidence base for smoking cessation uses a combination of behavioural interventions and drug therapy. Behavioural strategies may aim to maximise self-regulatory capacity and skills (e.g., strategies for reducing exposure to smoking cues) or encourage social support. When pharmacists advise patients on behavioural modification to support smoking cessation it should always be tailored to the individual.

Nicotine Replacement Therapy (NRT)

|

|

|

🎞️ Video 4: NRT ⏲️9:00 mins

NRT is the most widely available (unscheduled) and best tolerated form of pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation. NRT aims to reduce unpleasant nicotine withdrawal effects (craving, anxiety, irritability, hunger) by temporarily replacing low doses of nicotine from tobacco. Thus, NRT eases the transition from cigarette smoking to complete abstinence. It is safer than smoking and has low addictive potential. The choice of NRT depends on the level of nicotine dependence, patients’ preference and the suitability of individual formulations. Pharmacists must be able to discern and counsel on the safest, most efficacious and appropriate NRT regimen for a patient. They must also be able to recognise when a referral to a medical practitioner is warranted, such as when NRT is contraindicated.

Even though NRT is available in various formulations, all forms of NRT (at equivalent doses) have similar effectiveness in achieving smoking cessation. The transdermal patch is a long acting form of NRT and maintains steady-state nicotine levels to reduce withdrawal symptoms. Faster acting NRT formulations, such as gum, inhalers, lozenges and oral sprays are intended to be absorbed via the sublingual or buccal route. These formulations offer flexible dosing that can be adjusted to reduce breakthrough cravings.

Combination NRT involves using a long-acting patch plus a faster-acting formulation and it is safe and more effective than NRT monotherapy. NRT is usually well tolerated and some adverse effects such as sleep disturbance, dizziness, weight gain, and headache may also be related to stopping smoking. Other adverse effects may be related to the NRT dosage form, such as application site reactions from the transdermal patch and throat or mouth irritation from the gum, lozenge, inhaler and oral spray. Learn more about the different forms of NRT available below:

Australian guidelines recommend the following initial NRT doses:

- Smokes within 30 minutes of waking and smokes >10 cigarettes a day

- Highest-strength patch + highest-strength gum OR highest-strength lozenge OR 1 mg oral spray OR 15 mg inhaler

- Smokes within 30 minutes of waking and smokes ≤10 cigarettes a day OR smokes more than 30 minutes after waking and smokes >10 cigarettes a day

- Highest-strength patch + lowest-strength gum OR lowest-strength lozenge OR 1 mg oral spray OR 15 mg inhaler

- Smokes more than 30 minutes after waking and smokes ≤10 cigarettes a day

- Lowest-strength gum OR lowest-strength lozenge OR 1 mg oral spray OR 15 mg inhaler.

Titrate the dose according to the patient’s withdrawal symptoms. Underdosing can undermine a patient’s confidence in treatment. Patients with high nicotine dependence may benefit from use of two patches at the same time, however, the evidence supporting the use of two patches is inconclusive. Tapering the dose of NRT at the completion of a course of treatment does not influence successful long-term smoking cessation. Patients who have successfully stopped smoking after an initial 8-week course of NRT may consider a follow-up course. The optimal duration of NRT has not been established.

Planned follow-up increases cessation rates. Suggest that patients return for follow-up within 1 week of the stop smoking date and for additional planned follow-up visits to review progress. Invite the patient to contact the pharmacy if they have any questions or concerns about NRT or the advice provided. If relapse occurs, offer support and encourage further attempts. Acknowledge that it often takes numerous attempts to stop smoking.

Patients are unsuitable for NRT and should be referred to a medical practitioner instead in the following situations:

- Age <12 years.

- Pregnancy.

- Patient wishes to use a prescription medicine for smoking cessation.

- A medicine the patient uses may require a dose change when they stop smoking because tobacco smoking affects the metabolism of caffeine and many drugs, including antipsychotics, antidepressants and some antithrombotic drugs (e.g., warfarin).

NRT should be supplied to patients and concurrently referred in the following circumstances:

- Co-morbidities such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes or mental illness.

- Age 12-18 years.

- Breastfeeding

The following table from eTG summaries different forms of NRT: AMG2-Nicotine-replacement-v4 (1) (1)

Other Pharmacotherapy for Smoking Cessation

|

|

🎞️ Video 5: Other Pharmacotherapy for Smoking Cessation ⏲️5:15 mins

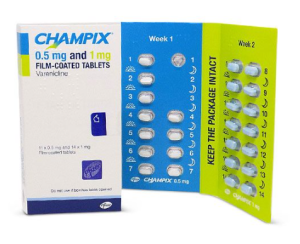

Varenicline is the most effective drug therapy for smoking cessation, closely followed by combination NRT. Each of these is more effective than NRT monotherapy or bupropion. Bupropion is an option when combination NRT and varenicline are not suitable, though it is less effective. Nortriptyline is an option when first-line drug therapies (NRT, varenicline and bupropion) are not suitable or were not effective after an adequate trial. Nortriptyline is a second-line choice and is not approved by the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) for the management of tobacco smoking.

E-cigarettes and Vaping for Smoking Cessation and Nicotine Dependence

|

|

|

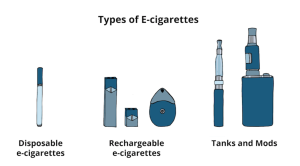

Nicotine vaping devices are also known as e-cigarettes and vapes. These products are liquids used in devices that allow people to inhale aerosolised liquid nicotine. Nicotine vaping products are an alternative for use when first-line drug therapies (NRT, varenicline and bupropion) are not suitable or were not effective after an adequate trial. However, evidence for efficacy is evolving and long-term safety is not certain. There are currently no vapes for smoking cessation or the management of nicotine dependence included in the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (ARTG). There are established pathways for patients to lawfully access unapproved goods, but these goods are not assessed by the TGA for quality, safety and efficacy or performance.

State and territory laws require vapes containing nicotine to be prescribed under the Special Access Scheme (SAS) or Authorised Prescriber (AP) scheme and dispensed in a pharmacy setting. It is illegal for retailers such as tobacconists, vape shops and convenience stores to supply any type of vape, even with a prescription. From 1st October 2024, therapeutic vapes with a nicotine concentration of 20mg/mL or less will be available in pharmacies to patients 18 years or over without a prescription. A pharmacist will need to be satisfied it is clinically appropriate, and meet several other conditions, to supply a vape to a patient without a prescription. These changes will help facilitate patient access while maintaining appropriate controls and protections.

The only vaping products that can lawfully supplied are the products on this list: https://www.tga.gov.au/products/unapproved-therapeutic-goods/vaping-hub/table/list-notified-vapes

Download the lecture notes here:

COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING

This material has been reproduced and communicated to you by or on behalf of James Cook University in accordance with section 113P of the Copyright Act 1969 (Act).

The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further reproduction or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice.