1.3.1 Stable angina

Introduction to Stable Angina

|

|

|

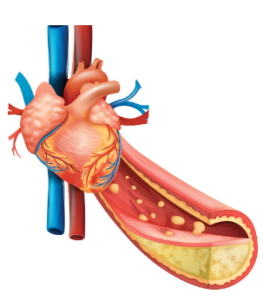

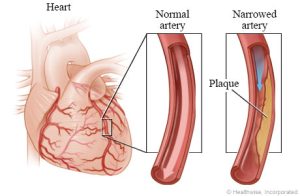

Angina indicates an imbalance in myocardial oxygen supply and demand. It is typically caused by some form of artherosclerotic obstruction of the coronary arteries. This obstruction is usually a build up of hardened fats, cholesterol and other substances in and on the artery walls, known as a an atherosclerotic plaque. This plaque can occlude blood flow to myocardial tissue. The reduced blood supply causes a temporary deficit of oxygen in the myocardial tissue. As a result, there is build-up of lactic acid from the metabolism of sugars to maintain energy supply. Remember that the heart typically uses aerobic metabolism for the production of energy and rarely the use of glucose or glycogen in anaerobic metabolism. Lactic acid buildup is the reason why retrosternal pain is the the most common symptom of stable angina.

Stable angina is one of the most common ischaemic syndromes. Other ischaemic syndromes include unstable angina and myocardial infarctions which are discussed later in the trimester. It is important to note that stable angina differs to the other ischaemic syndromes but it can still progress onto unstable angina or a myocardial infarction if not treated appropriately. The main difference between stable angina and the other ischaemic syndromes is that it is not associated with myocardial tissue damage, changes on ECG or elevation of cardiac markers. It is constant in duration and severity and has a predictable onset and pattern of symptoms. The retrosternal chest discomfort is usually brought on by exertion, emotional stress or cold temperatures, lasts for 10 minutes or less and subsides with prompt rest. You will learn later this trimester that in comparison, a myocardial infarction is associated with symptoms that occur at rest, more severe pain and a longer duration of pain and these symptoms may not respond to nitroglycerin (which we will discuss soon).

There are three types of angina, plus unstable angina. Explore the pathophysiology of the three types of angina below.

All of these different types differentiate in cause mostly. The treatment of these different types of angina overlap. For the purpose of this module, we will concentrate on the management of stable angina as it is by far the most common type.

📺 Watch the vodcast on the introduction to stable angina. (12:51 minutes)

Prevalence of Stable Angina

|

|

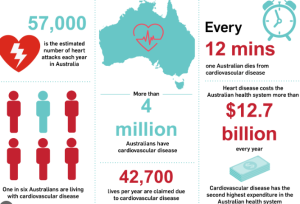

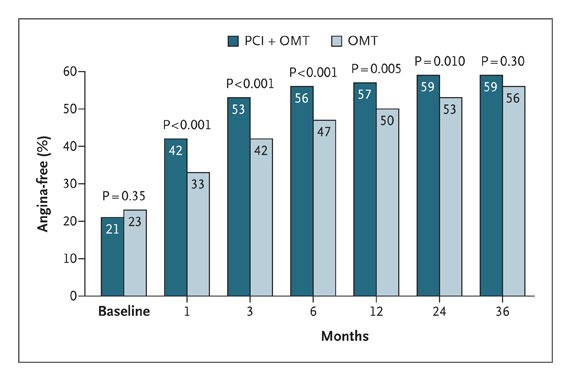

Angina pectoris, a common manifestation of coronary artery disease (CAD), affects a significant portion of the population. Approximately 29% of patients with stable angina experience symptoms at least once a week. Effective management of angina often involves a combination of optimal medical therapy (OMT) and percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Studies indicate that patients receiving both OMT and PCI have a higher likelihood of remaining angina-free compared to those on OMT alone (Weintraub et al., 2008).

Freedom from Angina over Time as Assessed with the Angina-Frequency Scale of the Seattle Angina Questionnaire, According to Treatment Group.

Freedom from Angina over Time as Assessed with the Angina-Frequency Scale of the Seattle Angina Questionnaire, According to Treatment Group.

OMT denotes optimal medical therapy, and PCI percutaneous coronary intervention

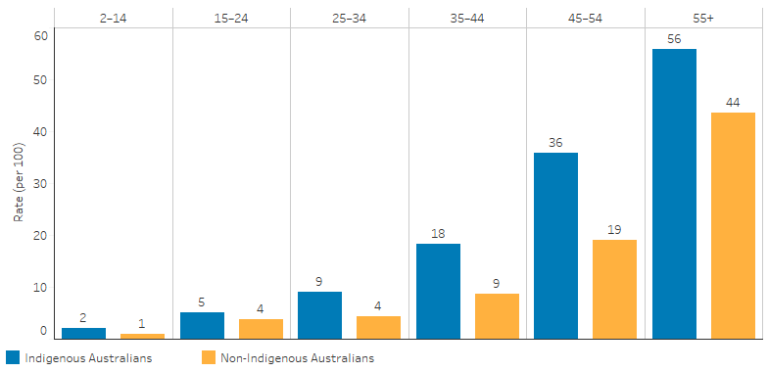

In Australia, an estimated 580,000 adults (3.1% of the population) have experienced coronary heart disease (CHD) at some point, with 227,000 reporting episodes of angina. The incidence of stable angina is notable, with over 72,000 hospital admissions in 2018 alone. Angina rates are higher in males compared to females and increase with age. Furthermore, Indigenous Australians are disproportionately affected, with 16% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people aged 2 and over reporting cardiovascular disease, including angina. The prevalence of cardiovascular disease is notably higher in remote Indigenous communities (18%) compared to non-remote areas (15%) (AIHW and ABS analysis).

Source: Table D1.05.2. AIHW and ABS analysis of National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey 2018–19 and National Health Survey 2017–18

Source: Table D1.05.2. AIHW and ABS analysis of National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey 2018–19 and National Health Survey 2017–18

Note in the figure above, the incidence of CVD increases with age and across all age groups, the incidence of CVD (including angina) is higher for Indigenous Australians (in blue) compared with non-Indigenous Australians (in yellow).

📺 Watch the vodcast on the incidence of stable angina. (5:08 minutes)

Risk Factors for Stable Angina

|

|

|

Angina pectoris risk factors are categorized into modifiable and non-modifiable types. Turn the cards below to learn more about the modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors for stable angina. Make sure you flip both card 1 and card 2!

Check your understanding

📚 Read/Explore

Revision activity: Remember David from Chapter 1.3? What modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors did David have?

- Hint:

- Poorly Controlled Hypertension: David’s history of hypertension that is not well managed increases the risk of coronary artery disease, which can lead to angina.

- Age: David is 54 years old, and the risk for angina increases with age.

- Hyperlipidemia: High cholesterol levels contribute to the development of atherosclerosis, increasing the risk of angina.

- Lifestyle Factors: Factors such as smoking, sedentary lifestyle, and obesity, if present, would further increase the risk for angina. David may have none of these though his BMI is 27, suggesting he is a little overweight.

Non-Drug Management for Stable Angina

|

|

|

To effectively manage and mitigate risk factors that exacerbate angina, general lifestyle modifications that reduce CVD risk should be adopted, such as those from the National Heart Foundation of Australia. Addressing modifiable risk factors through specific lifestyle changes is crucial for preventing the progression of stable angina to more severe coronary ischemic syndromes. General lifestyle changes that reduce the risk of stable angina progressing to more severe coronary ischemic syndromes apply to almost every cardiac condition. These are smoking cessation, nutrition, alcohol reduction/modification and exercise (which we have already covered in the previous chapter). In addition to these, patients with stable angina should be screened for sleep apnoea and receive the annual influenza vaccination. Use the accordion below to explore lifestyle changes to prevent the progression of stable angina.

Check your understanding

Overall Drug Management of Stable Angina

|

|

|

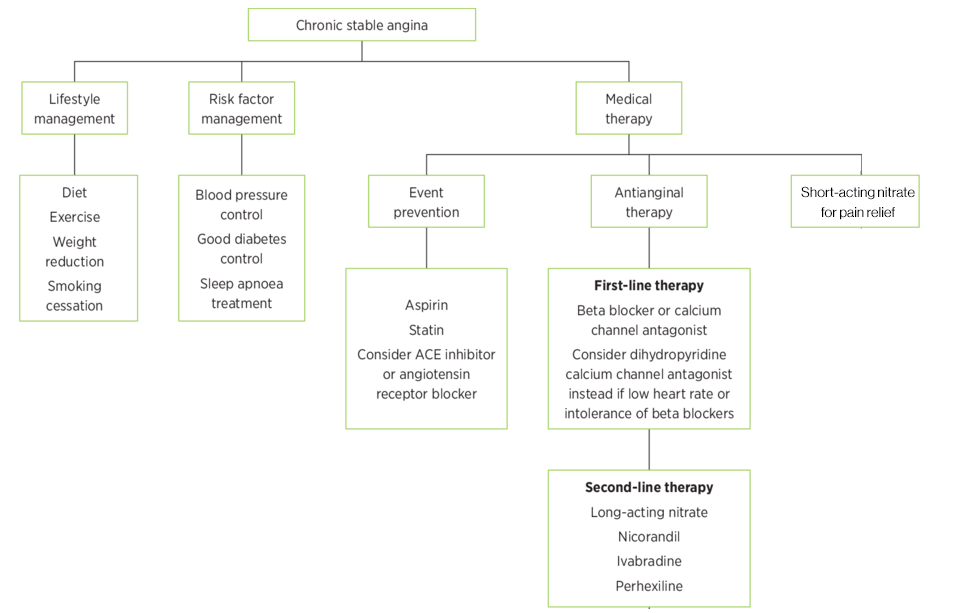

Managing stable angina over the long term requires careful medication management to balance oxygen supply and demand, thereby alleviating symptoms and preventing progression of the disease. There are three main components to the pharmacological management of angina. These include:

- Symptomatic relief for an acute episode of angina.

- A short acting nitrate (glyceryl trinitrate) is used sub-lingually for rapid symptomatic relief.

- Antianginal therapy to re-balance the oxygen supply/demand equation.

- A beta blocker is used first line.

- A calcium channel blocker (dihydropyridine and non-dihydropyridine CCBs) is used second line.

- A combination of the above (noting interactions) or the addition of long-acting nitrate therapy is third line therapy.

- Alternatively, use of other (fourth) last-line agents such as nicorandil, ivabradine or perhexiline could be considered.

- Secondary/Event prevention for patients with stable angina.

- Antiplatelet drug therapy, blood pressure and cholesterol lowering medications are used to prevent worsening of angina.

The figure below describes the overall lifestyle and pharmacological management of stable angina. This week, we will focus on the pharmacology of beta blockers, calcium channel blockers, nitrates and antiplatelets. Next week, we will talk more about medications to lower blood pressure and cholesterol.

Beta-Blockers: First-line therapy for stable angina typically involves beta-blockers such as metoprolol or atenolol. These medications work by reducing the heart rate and the force of contraction, which lowers the heart’s oxygen demand. This is particularly beneficial during episodes of angina, as it helps prevent the imbalance between oxygen supply and demand that causes chest pain. Beta-blockers are cardioselective, meaning they specifically target beta-1 receptors in the heart, which helps reduce the risk of adverse effects on other parts of the body. Metoprolol and atenolol are preferred due to their selectivity and effectiveness in managing chronic angina. However, it is important to remember that beta blockers are not cardiospecific. This means that in high doses they can still act on beta-2 receptors in the lungs, for example. Beta blockers are first line because they not only help in controlling angina symptoms but also have proven benefits in reducing the risk of heart attacks and improving overall cardiovascular outcomes.

Calcium Channel Blockers: When beta-blockers are not tolerated, are contraindicated, or if additional symptom control is needed, calcium channel blockers (CCBs) become an important part of the treatment regimen. These drugs are categorized into two main groups: dihydropyridine and non-dihydropyridine CCBs.

- Non-Dihydropyridine CCBs: Drugs such as diltiazem and verapamil fall into this category. They work by reducing heart rate and myocardial contractility, which helps decrease oxygen demand. Additionally, they have a vasodilatory effect that reduces the workload on the heart by lowering blood pressure and decreasing the heart’s oxygen requirements. Non-dihydropyridine CCBs are particularly useful in patients who cannot tolerate beta-blockers.

- Dihydropyridine CCBs: Medications like amlodipine and modified-release nifedipine belong to this group. They primarily work by relaxing blood vessels, which lowers blood pressure and reduces the heart’s workload. They are effective in managing angina by improving coronary blood flow. They are usually added to a beta blocker if symptoms are not controlled with the beta blocker alone. The combination can provide enhanced control of angina symptoms while minimizing the risk of adverse effects associated with higher doses of a single class of medication. It’s crucial to monitor for potential interactions and side effects, such as hypotension or bradycardia, especially when combining medications. The combination of a beta blocker and a non-dihydropyridine CCB’s (diltiazem or verapamil) is contraindicated due to the risk of severe bradycardia and heart block.

Long-Acting Nitrates: If angina remains inadequately controlled despite the use of beta-blockers and calcium channel blockers, long-acting nitrates like transdermal glyceryl trinitrate or modified-release isosorbide mononitrate may be added. These agents help to further alleviate symptoms by dilating blood vessels and reducing myocardial oxygen demand.

For example, treatment to prevent episodes of angina could consist of:

- Beta blocker (atenolol or metoprolol)

- Non-Dihydropyridine CCB (diltiazem or verapamil)

- Beta blocker (atenolol or metoprolol) + dihydropyridine CCB (metoprolol of nifedipine MR)

- Beta blocker (atenolol or metoprolol) + long acting nitrate (GTN patch or ISMN MR)

- Non-dihydropyridine CCB (diltiazem or verapamil) + long acting nitrate (GTN patch or ISMN MR)

These anti-anginal agents are used alongside GTN sublingual spray PRN for acute attacks as well as medication for secondary prevention of CVD.

📺Watch the vodcast on the management of acute angina with a nitrate. (3:13 minutes)

📺 Watch the vodcast on the medical management of stable angina. (17:37 minutes)

Summary

- Stable angina occurs due to an imbalance between oxygen supply and demand, resulting in anaerobic metabolism of glucose or glycogen and the formation of lactic acid.

- Lifestyle modifications such as diet modification, weight loss, exercise and smoking cessation improve outcomes. In addition, patients with stable angina should be screened for sleep aponea and receive the annual influenza vaccine.

- Rapid symptomatic relief from an acute attack of stable angina can be achieved with a short-acting sublingual nitrate. They are typically prescribed unless contraindicated.

- Anti-anginal therapies typically aim to re-balance the oxygen supply/demand equation. Drugs like beta blockers and non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker reduce heart rate and thus oxygen demand. Common alternative anti-anginal therapies include dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers and long-acting nitrate therapy.

- Prevention strategies include the use of an anti-platelet agent, the reduction of cholesterol, the reduction of blood pressure via the use of ACE inhibitors.

Check your understanding

Download the lecture notes here:

COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING

This material has been reproduced and communicated to you by or on behalf of James Cook University in accordance with section 113P of the Copyright Act 1969 (Act).

The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further reproduction or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice.