Module 4. Asset management: An Australian defence perspective

Asset management: An Australian defence perspective

Overview

As discussed before, there are different types of assessment management (AM), normally clustered by the nature of the business and/or asset, such as digital, fixed, IT, enterprise, financial and infrastructure AM. One Industry that integrates almost each of these AM types, is the Australian Defence sector. Capital-intensive industries such as the Australian Department of Defence, face a number of common challenges when it comes to managing their physical assets, such us budget restrictions, internal and external cultural and regulatory variances and maintaining the asset’s value over its life cycle while managing operational safety and much more.

There are a number of factors that contribute to increased complexity faced by the Department of Defence, including its national security mandate, the requirement to function within the Commonwealth’s legislative and accountability framework, as well as the unique character and interdependence of numerous Defence assets. Defence assets also generally have lifetime lengths measured in decades, which manifest a distinct set of issues in asset administration.

The importance of language and internal culture cannot be overstated. To begin, certain clear ideas and vocabulary within the defence business must be specified, so that we all understand the same meaning when a phrase is used in the same context. For example, “ensure,” “assure,” and “assurance” are some of the most important phrases (and ideas) that, in different contexts, may mean different things to different people. If working in the Air Domain then the most appropriate definitions should come from “The Defence Aviation Safety Framework”, since it is already extensively recognised within the Air Domain and because the concepts are quite similar.

When defence uses the phrase “through-life asset management”, it indicates a desire to accept some of the concepts of ISO 55000 Asset Management; however, their way of perceiving value is not the same as other businesses will perceive it. Within this context, it is not solely about the asset financial value but about productivity value. Yet, this is not unique to the defence industry and we can say that it is also relative to the nature of the organisation’s operation, their project objectives and the business/organisation strategy.

It is critical to concentrate on AM and on the productivity value of assets. There are several essential factors in life cycle activities and asset care that support this given value — for example, availability, reliability, maintainability, dependability, and safety, to name a few.

But then again, it is also about the leadership and the supportive culture that enables effective AM frameworks. In addition, the governance of assets, their condition, life extension, and/or remedies are also significant factors to consider. Overall, people, leadership, culture, skills, and job management are all critical concerns than tend to be overlooked if the right leadership and governance aren’t in place. These are some of the issues highlighted in the case study below.

An organisation that follows the criterion of utilising assets to deliver performance and value to achieve their objectives will progressively enjoy the benefits of their efforts, and that is the case for our Defence Team. The following case study sheds light on some of the key aspects faced by our defence businesses. This case study has been a collaborative work, with contribution from WGCDR Maria Jimenez.

Case Study

From Asset Management to Governance: Air Domain Defence Governance Strategy

By WGCDR Maria Jimenez in collaboration with Associate Professor Carmen Reaiche

What is an Asset Management Culture?

Let’s start with setting the scene defining AM Culture. We have earlier discussed ISO 55001 standards and it has been clear that ISO 55001 does not refer to organisational culture per se (ISO 55001: 2014), however, this is inferred through Leadership Commitment and exercised through defining senior management’s roles and responsibilities. While not explicit, those who are involved in establishing thorough Asset Management processes and systems within organisations recognise the vital role of that an organisation’s culture plays in facilitating the success of the processes and systems required to operationalise asset management.

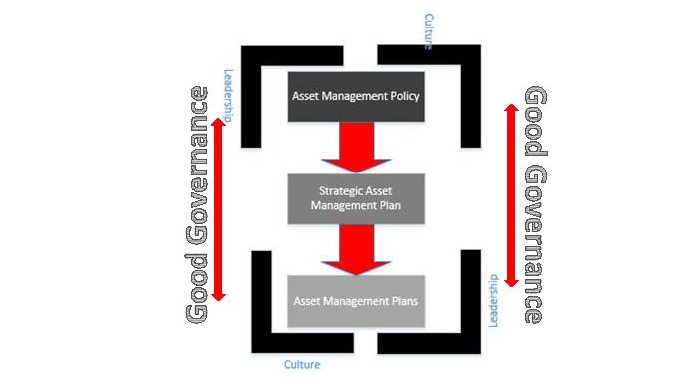

An Asset Management Culture is one based on the fundamentals of asset management (i.e. Value, Alignment, Leadership and Assurance) ensuring that the value from assets effectuates as depicted in Figure 11. Integral to the culture are:

- Strategic Asset Management Policies

- Strategic Asset Management Plans

- Integrating and Aligning Foundation processes and systems

- Organisation for effective and efficient Asset Management: Leadership Culture

- Good Governance Framework

But we should also explore the concept of culture itself.

What is culture?

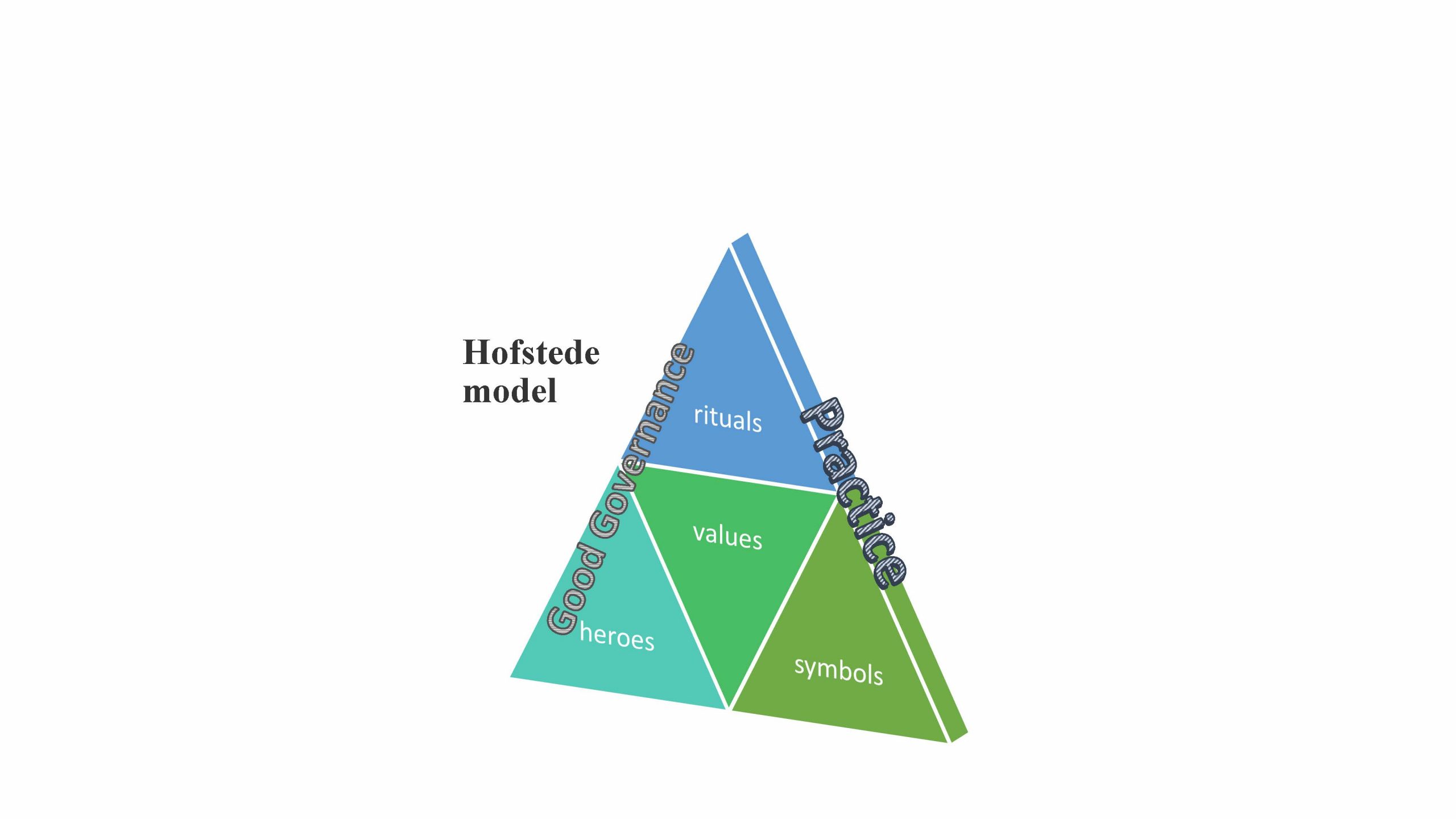

Across disciplines and over the years, researchers have adopted Hofstede’s (1980) definition of culture. Hofstede explains that culture is a cumulative set of characteristics that affect how people from a shared collective group respond to their surroundings. Within a business or industry, people operating under the same department and/or grouped by functionality (e.g. same field of expertise), share values, behavioural patterns and characteristics that are similar. This culture, also known as “the way we do things around here” strongly influences the organisation and its ability to thrive and deliver value.

There are many ways to visualise the concept of culture, Hofstede developed the “onion model of culture” approach, which has been used in this paper for Table 1. When someone looks at a culture from the outside, they need to work their way through understanding each layer to get to the core. Viewing culture as an ‘onion’ is where the core represents the value systems and the layers growing out of it represent habits. Adopting this pragmatic approach, we can say that based on an organisation’s strategy, objectives and goals one can create shared values that form a set of guiding “leadership” principles, and therefore fit within the values element for delivering capability. Figure 12 represents Hofstede model, in which each layer represents:

- Values – the beliefs and assumptions that provide a set of guiding principles for decision-making

- Rituals – the routine events which bring people together (or apart?)

- Heroes – those employees and managers whose status is elevated because they embody organisational values and therefore serve as leaders for others

- Symbols History – A shared narrative keeping people anchored to the key values of the organisation.

- Practice – the leadership required within an organisation and which works with formal policies or behind the scenes to communicate key information and influence behaviours.

This perspective on culture calls for a mutually shared cultural posture between the Australian Defence Force, Defence Industry and other external entities to support the procurement of highly complex systems.

Asset management in defence

Unlike private industry, Defence application of Asset Management practices calls for a divergent approach due to factors such as economics, capability (as opposed to assets) preparedness and interoperability. We explain the context of these factors below.

From an economics perspective, defence operates in a monopsony, where barriers of entry are too high to operate in a typical supply/demand economic environment. Contracts are complex, ambiguous with lengthy commercial arrangements and limited alternative sources of supply

Capability in an Asset Management defence context is the measure of success applied to the effectiveness of the use of the assets. Capability is defined as “the power to achieve a desired operational effect in a nominated environment within a specified time and to sustain that effect for a designated period” (ADDP 00.2). Hence, the optimisation of cost, performance and risk should result in an increased level in achieving the effect on operations.

The Capability and Acquisition Support Group (CASG) requires a tailored application of the ISO55000 Asset management to manage defence products. A Product in defence terminology is described as “a group of related assets to which coordinated acquisition and sustainment activities are applied” (ADDP 4.1). Consequently, Product Management comprises of all the entities that contribute value to the accomplishment of the Product Management Objectives (Product Management Guide 101)

Contrasting with private industry, where for example, a Haul Truck in the mines will perform one single function and controlled by a single entity; military capability is required to “act together, to provide services to or from, or exchange information with partner systems, units or forces” (Australian Defence Glossary v.1.0). Interoperability sets the environment to achieve unity of effort and increases the value of the assets by achieving a greater combined effect (Interoperability Guidance v1.0). We suggest that interoperability adds another layer of complexity characterising Asset Management in defence unique in comparison to other industries.

Limited availability of sources of supply and the complex nature of these contracts demands a greater degree of investment between defence and the defence industry, both economic and relational, to ensure a cohesive approach in the procurement of military capability. Ideally, the ADF seeks a Governance philosophy from industry partners, underpinned by behaviours such as benevolence, trust, collaboration and integrity. These behaviours provide a fundamental basis of shared values and by default a common culture, withstanding the testing of the commercial relationship. Table 1 illustrates the divergent cultural approaches to Asset Management (Product Management) and consequently why positive enterprise behaviours are essential in a defence context.

As mentioned above, the table below attempts to illustrate the Defence AM culture using Hofstede’s lens.

Table 1. Cultural perspectives of asset management/product management

| Onion Model | Asset Management – External Industry | Defence Product Management |

| Value | Asset integrity. The function of Assets Management is to support the delivery of services to the organisation | Capability |

| Rituals | Stimulate performance growth and minimise errors | Relationship |

| Heroes | Leaders in industry reflecting behaviours which support commercial operations | Military leadership focussing on best for capability |

| Symbols | ISO555001 | Product Management Framework |

| Practices | Commercial drivers focussing on cost minimisation | Governance (planning, assurance, reporting and contract administration) |

It is not our intention to discuss the general aspects of organisational culture in this case study, as this is a complex discipline on its own and it has been well argued in the literature. However, this case study aims to discuss some key points relating to organisational culture which we consider of relevance to Asset Management, Governance and ISO 55001. We suggest that as part of exercising leadership in an organisation a Steward’s purpose in a productive environment is to cultivate assets and grow them successfully for the benefit of employees, customers, investors, suppliers and society. Within this process a Steward’s approach will also enable the foundations for a solid governance framework.

Following this logic, before changes are implemented to an existing organisational culture of asset management, the issue of how to conceptualise and measure asset management culture must be addressed as a first step. Our Asset Management culture, then, will be the way that these elements interact to shape the management of – and indeed the way we think about – our assets. These elements therefore provide a valuable basis for informing us as to how we might influence Asset Management culture in defence but do not in themselves answer our question with regards to what “Product Management” looks like. To do this, we introduce a relational framework (Jimenez 2019), depicted in Figure 12 that we believe demonstrates ‘what good looks like’ in a defence Asset Management culture as opposed to less effective and reactive cultures.

How to establish an asset management (product management) culture in defence

Changing organisational culture is difficult. Managing change takes considerable time and other resources, which aren’t necessarily at reach on a day to day basis. There is an entire literature written on this topic, and a detailed examination of this topic is out of the scope of this module. However, based on our experience, soft skills, particularly “leadership” is the starting point to deliver sustainable change towards achieving an effective Asset Management culture.

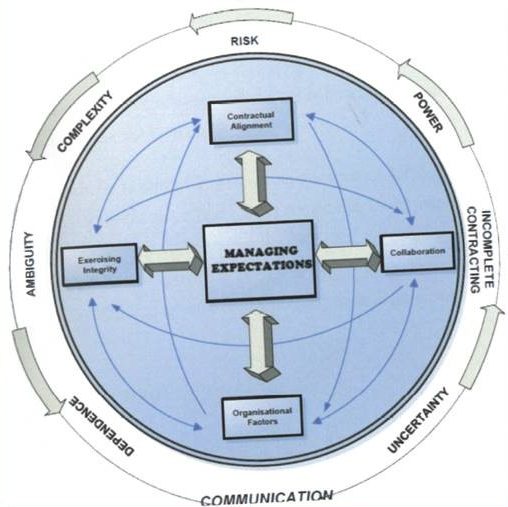

Historically, the ADF has been more comfortable using Management Tools rather than Leadership Tools. However, those that swing the balance to increase their use of Leadership Tools frequently achieve great results – these are the practitioners that encourage soft skills deployment. Indeed, ISO 55001 makes several references to the role of top management and leadership in establishing sound asset management practices. Many of the activities expected of top management in ISO 55001 are managerial in nature (for example, ensuring that an Asset Management Policy, Strategic Asset Management Plan etc are established). However many are true leadership activities and involve behaviours such as integrity, collaboration, organisational integration and contractual alignment. The following model (Figure 13) depicts how relationships within the Defence Asset Management system can be leveraged using a leadership lens rather than a managerial one.

Taking a leadership perspective (being one of the fundamental concepts of Asset Management) we explain how the dimensions of the model offer a robust foundation to establish and maintain a successful Asset Management (product management) culture in defence. As per Jimenez (2019), ‘collaborative’ behaviours are necessary to lead cross-functional teams. These behaviours support the ISO55001 operating principles, which promote a cross-disciplined approach in the operationalisation of the Asset Management system. Similarly, ‘exercising integrity’ is demonstrated from a Leadership lens through personal actions and interpersonal relationships focussing on ‘best for capability’. Leadership in ‘contractual alignment’ relies on the relational governance and assurance placed on the capability. Alignment (another fundamental of Asset Management) refers to how the asset base contributes to achieving value. That is, we determine contractual outcomes, associated measures and we are able to trace value through aligned objectives. Lastly, ‘organisational factors’ can be represented as the collective approach in contemporary leadership practices seeking to understand leadership in terms of teams, systems, networks and business units (McCauley & Palus, 2020). Organisational factors can be translated as ‘interoperability’ of the Asset Management as a system. Without these activities, a true Asset Management culture in defence cannot be established.

The Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Enterprise (CASE) and the product life cycle

In order to provide context to this section, in 2015 the Government implemented the recommendation from the First Principles Review recommending Defence focus on Planning and Governing with Defence Industry focussing more on managing and delivery (Air Domain Sustainment Commercial Strategy, 2022). This strategy emphasised a more collaborative approach to delivering capability, where the enterprise is collectively accountable for the acquisition and sustainment of the capability.

The Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Enterprise (CASE) model emphasises the relationships between the Capability Manager, industry and foreign governments to deliver capability to meet Defence’s preparedness and operational requirements (Agius 2021). The CASE model forms the commercial construct from which to deliver capability. Historically, defence’s commercial relationship with defence industry has been adversarial, however more recently there has been a shift towards strategic partnering with a focus on collective enterprise behaviours and attitudes, such as transparency and trust (Jimenez 2019, Air Domain Sustainment Commercial Strategy 2022), which best support best for capability outcomes.

Best for capability is a commonly used term in defence, which aims to elicit a decision making approach where all enterprise partners are equally accountable to engage and deliver what is required from acquisition, sustainment through to disposal activity. It may require undertaking actions and functions not necessarily bounded by the formal contract hence the need to influence, shape and apply leadership. The delivery of best for capability outcomes requires an integrated relational approach between the defence and industry partners to optimise capability life cycle activities and complement the commercial framework to achieve value for money (Air Domain 2022).

Commercial models call for a tailored approach due to the degree of complexity in the defence acquisition environment. In developing commercial models, the focus should be on the value proposition, optimised service delivery, total cost of ownership, a shared approach to risk and suitable levels of assurance. In this context, the product life cycle provides the basis for the commercial model. For example, at the commencement of the contract there is an increased level of financial risk, which often plateaus as the project progresses. Risk is again introduced towards the end of the capability’s life, as the capability ages and disposal of the assets commence.

Understanding the important relationship between asset management (product management) and governance

Understanding the relationship between Asset Management (product management) and governance is critical as it links the key principle of assurance to the value proposition. The Air Domain business goals articulate the management of governance and risk as one of its primary goals. Air Domain aim to implement governance controls to facilitate planning, assurance and leadership throughout the capabilities we manage (Air Domain Business Plan, 2022).

But let us define Governance. Governance is the combined effect of the organisation, people, processes and information applied practically to achieve that intent. Capability and Acquisition governance is centered on delivering value to customers, and optimising commercial, financial and capability outcomes (ASR Branch SPO Governance Guide). In Module 5 we will look at Governance in more detail.

The process of developing a Value Proposition consists of talking with customers to understand their needs; what tasks they need to achieve, challenges in achieving these tasks, what does good look like, or conversely what the customer wants more of. This information is communicated through agreements such as Materiel Acquisition Agreements (MAAs), Material Sustainment Agreements (MSAs) and Product Delivery Schedules (PDS). Creating the Enterprise Value Proposition facilitates the commercial relationship to develop a common understanding of capability requirements for the delivery of capability.

Let’s explore four of the key factors underlining Governance including: planning, assurance, contract administration and reporting (Agius 2021). Planning refers to the defining and establishing requirements and enterprise arrangements. Contract administration covers transactional activities such as implementation of contract change proposals, while the reporting function constitutes evaluation of contractor performance managed through various organisational tools. Commonly out of the four factors constituting the Governance framework, assurance is the most challenging to comprehend, apply and optimise at a tactical level.

First, we must delineate between ensure and assure. Assurance is defined as ‘a positive declaration intended to give confidence’, alternatively ensure is ‘to make sure, certain or safe’ (Sea King Board of Inquiry). Industry Partners are responsible for ensuring the delivery of materiel through assurance activities exercised by the Commonwealth (Agius 2021).

Assurance can be described as establishing ‘justified confidence’ based on objective evidence in the work done by and on behalf of the customer (Agius 2021). This ‘justified confidence’ is built on conditions such as risk exposure; interest alignment; accountability and compliance costs. Analysing these conditions will result in an appropriate and commensurate response to the degree of assurance applied to the supplier. For example, where risk is low, interest alignment is high, accountability is clear and compliance costs are low a lower level of assurance is applied. Low level of assurance can be applied through a relational governance framework such as the Jimenez (2019) model. The model supports the notion that assurance at a tactical level should concentrate on decision making for ‘best for capability outcomes’ and creating value by shaping and influencing the contractual relationship and exercising leadership.

Governance and supplier assurance

Assurance exists to monitor supplier performance, compliance to organisational requirements, identify contracting gaps and managing total cost of ownership of the capability (Air Domain Governance Strategy, 2020).In a defence context, it is critical that assurance activities are aligned to meet capability requirements, support internal organisational processes, improve utilisation of organisational resources and be optimised to meet risk, cost and performance, based on the value proposition. Thus, where a greater degree of assurance is required a more complex contractual structure may be more appropriate.

To what degree supplier assurance is undertaken is based on transparency, the creation of value, management of risks, issues and opportunities and application of relational contracting from an Enterprise or System lens. Transparency is necessary to establish trust, the greater the degree of trust between the parties the less assurance required (Jimenez 2019). Value creation is generated through activities positively related to supplier behaviour and outcomes, including leadership. Managing risks, issues and opportunities direct the assurance model, the management of these through relational contracting enhance the contractual relationship promoting trust which is necessary to the Enterprise. Assurance activities do not operate in isolation, they need to be executed as part of an integrated System (Air Domain Governance Strategy, 2020).

An Enterprise focussed approach is consistent and compliments ISO550001 which describes its aim of deriving value from the optimisation of cost, performance and risk. Optimising these occurs through the integration of capability management systems based on the constituent capabilities such as maintenance, engineering, and logistics.

In conclusion, implementing an ISO 55001-compliant Asset Management system will depend heavily on the commitment from leadership within both the defence and defence industry. Therefore a Stewardship culture enabled through the Jimenez (2019) model is critical in culturally aligning defence and industry, through the acquisition and sustainment of military capability.

Key Takeaways

- There must be consistent alignment between the capability objectives and the organisation’s objectives, as well as a recognition of how meeting culture leadership requirements contribute to the delivery of defence capability and the attainment of their strategic objectives.

- Governance is essential for effective AM within the Defence domain.

References

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related values. Sage.

Jimenez, M.I., & University of South Australia. (2010). An emerging relationship framework for managing complex military procurement projects.