Module 6. Core project governance principles

Overview

In previous modules we have introduced project governance and asset management (AM), aiming to provide you with an understanding of what governance includes and how to achieve good project governance. In this module, we will discuss the core or fundamental project governance principles. At its core, good project governance is based on people, structure, and information (OGC, 2009).

Project governance supports decision-making within a project. It is based on defining clear accountabilities and responsibilities, and is therefore crucial to achieving project outcomes. Consequently, good project governance provides logical, robust, and repeatable decision-making processes, ensuring a structured approach is adopted.

The literature highlights that project governance is fundamentally a set of relationships between key stakeholders, including the project manager, sponsor, owner, and key decision-makers (Turner, 2006). Thus, by setting a clear structure at the project onset and determining S.M.A.R.T objectives, we are in a better position to achieve effective project outcomes and monitor the project’s performance.

According to Turner (2006), there are three specific levels of governance within projects:

- Corporate: This is the central authority or decision-maker, and could include a board of directors or a committee that supports decision-making. This encapsulates the corporate governance requirements that each project must adhere to.

- Strategic: A broader context is provided as to why certain projects are undertaken and others are not.

- Project: Governance structures must exist at individual levels, supporting project delivery.

Corporate governance

Irrelevant of the size of an organisation, principles on project governance are set and based on the components of the organisation’s corporate governance principles. Corporate governance sets the management requirements for relationships across stakeholders and key decision-makers within and outside the organisation, providing a structure for which an organisation sets objectives, strategies and means to implementing and monitoring them (OECD, 2004).

According to the OECD (2004), good governance for organisations includes eight primary principles:

- roles and responsibilities

- accountability

- disclosure and transparency

- risk management and control

- decision-making

- ethics

- performance and effectiveness

- implementation of strategy.

These principles of good governance can be applied to project governance and set a good framework for the implementation of governance across both organisations and projects. However, there needs to be a separation between the project governance and organisational governance structures. The project structure needs to be precise, clear and provide mechanisms to support decision-making. Documentation needs to be completed, and provide clarity of decision-making (Garland, 2009). Therefore, we can establish that the adoption of clear governance principles should support decision-making, reduce time delays and budgetary inefficiencies. It will ensure that project decision-making is simple to follow and that it can be completed in a timely manner (Garland, 2009).

Core project governance

This module outlines eight core project governance principles, which have been adapted from the OECD corporate governance principles. There are various frameworks in the literature; however, we considered these eight principles appropriate, as well as pragmatic, within the field of project management.

Principle 1: Clear definitions of roles and responsibilities

The establishment of clear project roles and responsibilities is a vital step to the success of a project. The assignment of roles should include definitions of accountabilities, responsibilities, and performance criteria. When assigning these roles, anyone who is involved in the project should be documented and their interest and influence in the project needs to be considered. Therefore, stakeholder management is crucial to the development of these roles and responsibilities documents.

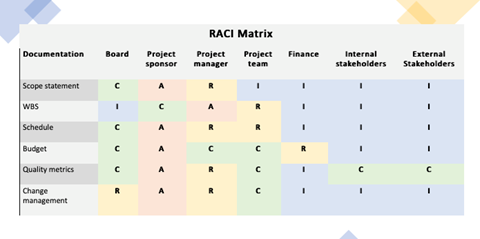

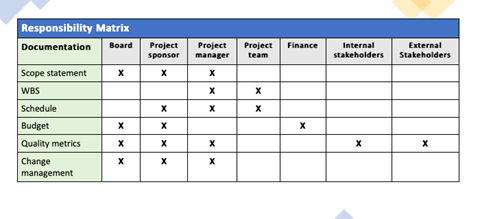

(1) Establish who has overall responsibility for the governance of the project management. This could be the project manager, project team, PMO or the board (it can also be a combination of these). Documentation of these roles and responsibilities can be shown through a RACI (Responsible, Accountable, Consulted, and Informed) matrix (example in Figure 16) or through a roles and responsibilities matrix (example in Figure 17).

(2) Identification of the roles, responsibilities, and performance criteria for the project team members. Key roles to be defined:

- The project sponsor is the person who is responsible for overseeing and ensuring project success. This includes the appointment of a project manager and their team, outlining the success criteria and ensuring successful project delivery (Tasmanian Government, 2008). They have three principal groups they are accountable for and to: the board, project manager, and project stakeholders.

- The board, steering committee, or governance committee is the primary body within the defined organisational and project governance structure (Tasmanian Government, 2008). They are responsible for responding to issues and risks which arise or could affect the project outcomes. A key role of this group is to ensure the outcomes of the project are met.

- The project manager is broad and flexible. They are responsible for overseeing the end-to-end management of a project. This includes resolving issues, determining tasks, sub-tasks, and activities, completing documentation, and monitoring and controlling the project (PMI, 2022b). There is no one-size-fits-all project manager definition. They report to and work with the PMO, governance committee, sponsor, project team and broader stakeholders.

- Project stakeholders are those individuals, groups or organisations who are either actively involved with the project, or who have interests in the outcome of the project (either positive or negative), or both (PMI, 2022a; APM, 2009). These stakeholders need to be engaged and communicated with as per a stakeholder management plan, each stakeholder will have different expectations of their roles and responsibilities within a project. Discussions with stakeholders should be held early in the project to establish their requirements, and updates are to be made throughout when roles change.

- The project team are those individuals who are working interdependently (or as a collective) to meet a common goal and who share specific responsibilities for outcomes of the project they are working towards (Sundstrom et al., 1990).

(3) Establishing relationships between all internal and external stakeholders who are involved in the project. This includes describing the flow of information and communication between these stakeholders. Development of a project stakeholder management plan can support this.

Principle 1 provides a clear outline of the roles and responsibilities of key members of the project team, decision-makers and relevant stakeholders, which feeds directly into Principle 2.

Principle 2: Single point of accountability for project success

A single point of accountability is vital to the success of any project. Through a single point, there is a clear understanding of who can approve each change and the process for leadership, and there is one person or group who is responsible for driving problem solutions. It is not enough to formally recognise just anyone as the accountable party. They must have the authority to make decisions within the organisation and they must be held accountable. To achieve this accountability, there should be agreed-upon criteria as well as agreement on formal governance arrangements. This includes clear allocation of authority for representing project owners, stakeholders, and other interested parties. Principle 2 links back to Principle 1 in ensuring that roles and responsibilities are clearly articulated.

The accountable officer or group should understand the terms of their roles and responsibilities, support stakeholder engagement, establish key performance indicators, and oversee project performance. Accountability parameters should be detailed in the Project Governance Plan to remain in place for the entire project (distinct to a Project Management Plan which is more detailed and only comes into existence during the development of the project).

Projects have many stakeholders and an effective project governance framework must address their needs. The next principle deals with the way this should occur.

Principle 3: Provision of transparency

Transparency in project governance processes provides visibility to how the project is progressing, including the quality of work being completed, any issues or risks and changes made (Hassim et al., 2011). Through visibility, stakeholders and sponsors have greater confidence in, and understanding of, the project management process (Danturthi, 2016). Transparency provides a mechanism for project team members to access relevant information in an easy and efficient manner (Danturthi, 2016). Information that may be of interest to the project team includes:

- Budget – allowing the team members to be aware of the amount they can spend and their work budget, ensuring they are completing what is expected of them.

- Schedule – ensuring they are on track with what was outlined within the timeline.

- Communication – clear manner for engaging stakeholders, through information that is both accurate and timely.

- Issues/risks that arise and how they were managed – shared problem-solving can be achieved by providing stakeholders and other project teams with information of issues that have arisen.

Transparency in project governance provides managers and sponsors with a heightened sense of responsibility to achieve outcomes (Danturthi, 2016). Principle 3 means that decisions and changes made are done in alignment with project roles and responsibilities, ensuring that they are documented and easily accessible to project team members and relevant stakeholders. This principle also requires that enough information is provided, that the information is also accurate, easy to understand and timely.

Principle 4: Risk management and control

Risk management and control within projects is the process of identifying, analysing and responding to risks that can arise during the project life cycle (Chapman & Ward, 1996). This forms a key part of governance, by ensuring that there is an appropriate review of risks which are encountered within the project (Raz & Michael, 2001). The process is not only reactive, it should be proactive, through the identification and planning of potential risks throughout the project lifecycle. Following the ISO 31000 risk management standard (ISO, 2018).

Risks are defined as anything which could impact a project’s schedule, performance, budget, or scope (Raz & Michael, 2001). There are different ways to manage risks within projects, including extensive and detailed planning for complex projects which outline mitigation strategies and treatment options. Conversely, risk management for simple projects can be a prioritised list of risks that are evaluated as high, medium, or low priority and influence.

The development of a risk management plan requires a clear project scope statement, to support the identification of risks (Raz & Michael, 2001). Each risk identified should be logged within a risk matrix, which helps in the prioritisation of the different risks, including if they will have a positive or negative impact on the outcomes. This is accompanied by the actions planned to mitigate the identified risks. The risk management plan should establish the review process, frequency of review and who is accountable.

Principle 5: Clear decision-making and change management process

Clear decision-making and change management processes are vital to ensuring the management of the project is effective and efficient. The decision-making process should outline the clear roles and responsibilities of the team, including who has the authority to make decisions and how they need to be documented and communicated (Garland, 2008). There needs to be consistency in the decision-making process applied to the requirements, policies and procedures provided by the organisation.

The change management process should flow from the decision-making process, whereby, the roles and responsibilities are clearly defined, along with the levels of authority of different decision makers. Within the change management process, the level of authority may be based on different criteria (Muller, 2009; Renz, 2007). For example, financial value, schedule impact, detail of scope change, response to risks or environmental changes are factors that influence authority levels. These criteria need to be set and documented at the beginning of the project. This will reduce complexity, confusion, and conflict by setting appropriate authorisation processes. Within the process, it should clearly dictate that approvals are required for each change.

Principle 6: Ethics

Each project should be based on ethical considerations and rules of law within the countries in which the projects are performed, operated or applied. Ethics within projects ensure that each accountable officer is doing work or making decisions in line with their legal competence and obligations, along with organisational governance requirements (OECD, 2004; UN, 2008).

Projects should be following the rule of law, ensuring that fair and legal frameworks are enforced impartially for all aspects of the project (including management, team performance management and resource use and allocation) (UN, 2008).

Best practices of project governance will provide equitable and inclusive outcomes and management planning processes (UN, 2008). It is important that every team member and most stakeholders feel that their views and expectations are considered and that they are not excluded. This requires all groups, including those most vulnerable, to be offered opportunities to share their views.

Principle 7: Project and project team performance and effectiveness

Project and project team baselines must be set to measure performance and effectiveness of the project team against, for example, scope, budget or schedule. By defining the criteria and frequency of measurement at the beginning of the project, reporting performance of the project status to stakeholders and sponsors will be managed as part of the process. The escalation and management of risks and issues as they arise will be shared in reporting processes.

Project team performance reporting should be shared if the team is working as efficiently and effectively as possible. These updates should share the time taken to achieve goals, and the cost to achieve these goals and outcomes and if they are in line with the plan. If not, why are they not in line? This requires the team to critically analyse their performance and share updates on what work they are prioritising and why.

Organisations who foster a culture of continuous improvement and sharing project successes and failures are more successful organisations and have greater levels of project success. This includes fostering trust and collaborative problem-solving processes with stakeholders (APM, 2004).

The reporting process should occur at all stages of the project, identifying how the project team and managers plan to realise the benefits of the project. Additionally, these updates should be timely, realistic, accurate and based on data (e.g., progress, achievements, forecasting and risks). This should utilise a mechanism to develop an independent review of how the project is going, what the aims are and how they are going to get there. Principle 7 should occur throughout the project and be a key component of Principle 8.

Principle 8: Implementation of governance processes

Implementation of project governance should be built into the project management plan, with specific authorisation points. These decisions should be documented and communicated to relevant stakeholders and project team members. Key components of implementation of governance and principles of project governance include:

- Creation of an agreed upon project business case, which outlines the project objectives, roles and responsibilities of team members and stakeholders, and the various resources and inputs required to obtain the project objectives.

- Authorisation points within the project plan need to provide clearly defined decision-makers, who have control over specific components of the project (e.g., change management).

- Project managers and leaders need to identify similar projects that are underway, which can support the use of resources and reduce conflict and inefficiencies.

- Formal agreements should be in place, defining processes for asset management.

Within the implementation principle, there is also a need to evaluate, review and implement improvements to support better governance processes in future projects. This can be achieved through learning and adopting new governance procedures. As governance is a process constantly being changed, reviewed, and improved, it is important to learn from mistakes or lessons learned and implement new or improved knowledge and skills (APM, 2007). Additionally, an education process should be implemented as part of the project team development stage (APM, 2007). This will ensure that all team members have the relevant skills and knowledge to implement project governance.

Reading: “Who has the D?: How clear decision roles enhance organizational performance”

Governance of project management principles

It is critical to highlight that according to the Association of Project Management (APM), there are 11 governance of project management principles (see Table 3), which support overarching corporate and project governance. This incorporates the above listed principles as well as methodologies, tools and activities which are used to support the ongoing and day-to-day management of the projects within an organisation (APM, 2004).

Table 3. Governance of project management principles (APM, 2004, p. 6)

| No. | Governance of Project Management Principles |

| 1 | Board has overall responsibility for project management governance. |

| 2 | Roles, responsibilities, and performance criteria for project management governance are clearly defined. |

| 3 | Disciplined governance arrangements, supported by appropriate methods and controls, are applied throughout the project life cycle. |

| 4 | A clear and supportive relationship is established between the overall business strategy and project. |

| 5 | All projects have an approved plan with authorisation points. Decisions made at authorisation points are recorded and communicated. |

| 6 | Members of delegated authorisation bodies have representation, competence, authority, and resources enabling appropriate decision-making. |

| 7 | The project business case is supported by relevant and realistic information and provides a reliable basis for making authorisation decisions. |

| 8 | The board and delegated agents decide when independent scrutiny of projects and project management systems is required and implement such scrutiny accordingly. |

| 9 | There are clearly defined criteria for reporting project status and for the escalation of risks and issues to the levels required by the organisations. |

| 10 | The organisation fosters a culture of improvement and frank internal disclosure of project information. |

| 11 | Project stakeholders are engaged at a level that is commensurate with their importance to the organisation and in a manner that fosters trust. |

According to APM (2004), by following these principles to support governance of project management, along with the corporate and overarching governance principles, organisations can avoid common project failures. You are probably familiar with some of these, which include:

- unclear link to strategic priorities

- poorly defined roles and responsibilities

- ineffective stakeholder engagement

- lack of project and risk management skills

- poor budgeting

- project breakdown unclear and ill-defined.

As a project manager and efficient project leader, adopting these principles will provide you and your team with guidance for best practices of project management governance. We recommend that these principles are used in conjunction with and as a support mechanism alongside the organisation’s selected project approaches and methodologies.

Test Your Knowledge

Key Takeaways

- Project governance is the management framework within which project decisions are made.

- According to A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide), project governance is an “oversight function that is aligned with the organisation’s governance model and encompasses the project life cycle.”

- Project governance is often referred to as the three key pillars — structure, people, and information.

References

APM. (2004). Directing change: A guide to governance of project management. Association for Project Management.

APM. (2007). Co-Directing Change: A guide to the governance of multi owned projects. Association for Project Management.

APM. ( 2009). Sponsoring change: A guide to the governance aspects of project sponsorship. Association for Project Management.

Chapman. C., & Ward, S. ( 1996). Project risk management: Processes, techniques and insights. John Wiley.

Danturthi, R. S. (2008). Transparency in project management. Project Management Institute. https://www.projectmanagement.com/contentPages/article.cfm?ID=358236&thisPageURL=/articles/358236/Transparency-in-Project-Management#_=_

Garland, R. (2009). Project governance: A practical guide to effective project decision making. Kogan Page.

Hassim, A., Kajewski, D., & Trigunarsyah, B. (2011). The importance of project governance framework in project procurement planning. The Twelfth East Asia-Pacific Conference on Structural Engineering and Construction, 14, 1929-1937.

ISO. (2018). ISO 31000: Risk management guidelines. https://www.iso.org/standard/65694.html

Müller, R. (2009). Project governance. Gower Publishing.

OGC. (2009). Managing successful projects with PRINCE2. TSO

OECD. (2004). OECD Principles of corporate governance. OECD.

PMI. (2022a). Stakeholder analysis pivotal practice projects. Project Management Insititute. https://www.pmi.org/learning/library/stakeholder-analysis-pivotal-practice-projects-8905

PMI. (2022b). Who are project managers? Project Management Insititute. https://www.pmi.org/about/learn-about-pmi/who-are-project-managers

Raz. T., & Michael. E. (2001). Use and benefits of tools for project risk management. International Journal of Project Management, 19, 9-17.

Renz, P. S. (2007). Project governance: Implementing corporate governance and business ethics in nonprofit organizations. Physica-Verl.

Sundstrom, E., De Meuse, K. P., & Futrell, D. (1990). Work teams: Applications and effectiveness. American Psychologist, 45(2), 120–133.

Tasmanian Government. (2008). Project management fact sheet: Steering committee “nuts and bolts”. Tasmanian Government. https://www.dpac.tas.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/509305/Steering_Committee_Nuts_and_Bolts_Fact_Sheet.pdf

United Nations. (2008). What is good governance? UNESCAP. http://www.unescap.org/pdd/prs/projectactivities/ongoing/gg/governance.asp.