7. Developing Positive Working Relationships

Learning Objectives

In this chapter, you will learn how to:

- cultivate meaningful professional relationships across all levels of your organisation, from support staff to senior leadership, while understanding the unique value each relationship brings to your professional development

- analyse and adapt to workplace cultures by recognising both explicit and implicit organisational norms that influence professional relationships

- implement specific strategies for building and maintaining positive workplace relationships through effective communication, professional boundaries, and collaborative approaches.

Imagine this Scenario

Zhang stares at his computer screen, the Micro-Cap software displaying yet another error message. His shoulders tense as he reads the technical documentation for the third time, trying to understand why the circuit diagrams won’t import correctly. After twenty minutes of unsuccessful troubleshooting, he finally gathers the courage to ask for help.

“Excuse me, John,” Zhang says, careful to pronounce each word clearly. “Could you help me with Micro-Cap? I cannot get these diagrams to import.”

John, or “Johnno” as everyone calls him, swivels in his chair, flashing a friendly smile and slides on over next to Zhang, looking at his screen. “What you got is pretty old hat, mate. Dunno how to get around it, Micro-Cap ain’t my bowl of rice. Have a yarn with Sunil, that cobber will get you sorted lickety-split.”

Zhang blinks, understanding perhaps half of what Johnno has said. After three months of studying engineering in Australia, he thought his English was improving, but this conversation makes him feel like he’s back on his first day. The words individually make sense. He knows what a bowl is, and rice, and yarn is something to do with string, but strung together, they might as well be another language entirely.

In the open-plan office, Zhang feels acutely aware of being one of only three non-Caucasian employees in the fifty-person firm. The fluorescent lights seem suddenly brighter, the air conditioning a bit colder. He considers returning to his desk to spend another hour with the technical documentation, but remembers his supervisor’s encouragement to ask questions when stuck.

With careful steps, Zhang makes his way to the IT department, where he finds Sunil engrossed in what appears to be several lines of code across multiple monitors. Like Zhang, Sunil wasn’t born in Australia, having moved from Bangalore five years ago.

Zhang hovers uncertainly in the doorway of the IT department. Through the glass walls, he can see someone who must be Sunil working intently across multiple monitors. Zhang’s hand tightens around the notebook where he’s written his technical question in careful English. After several deep breaths, he gently knocks on the door frame.

“Ex-excuse me,” Zhang’s voice comes out quieter than intended. “Are you Sunil? John, I mean, Johnno, said you might be able to help with Micro-Cap?”

Sunil startles slightly at the interruption, taking a moment to transition his attention from the code on his screens. He turns in his chair, adjusting his glasses as he faces Zhang. “Yes, that’s me,” he responds, his voice carrying a hint of an Indian accent. “You must be the new intern?”

“Yes, I am Zhang,” he says, still standing in the doorway. “I’m sorry to interrupt your work…”

“No, no, please come in,” Sunil gestures to a spare chair, though his smile seems a bit reserved, perhaps remembering his own early days as the newcomer. “What seems to be the problem?”

Zhang edges into the room, carefully pulling the chair to maintain a polite distance. He opens his notebook, pointing to his carefully written notes about the technical issue. As he explains the Micro-Cap problem and his confusion about Johnno’s response, his voice grows steadier.

Sunil’s initial reserve begins to fade as he recognises the familiar struggle of navigating both technical challenges and Australian workplace culture. His smile becomes more genuine as he shares his own experience.

After Zhang explains both his technical issue and his confusion about Johnno’s response, Sunil chuckles knowingly. “Ah, welcome to Australian English. Let me translate, ‘old hat’ means outdated or old-fashioned, ‘bowl of rice’ is Johnno’s attempt at being culturally relevant but missing the mark a bit, ‘have a yarn’ means to have a chat, and ‘cobber’ is mate or friend. As for ‘lickety-split,’ that just means quickly.”

Seeing Zhang’s overwhelmed expression, Sunil continues more gently. “Look, I know it’s a lot to take in. When I first started here, I spent half my time confused by these expressions too. The good news is, most people here are like Johnno: they mean well, even if their attempts at cultural connection sometimes miss the mark.”

Whilst helping Zhang resolve the Micro-Cap issue, Sunil shares more insights about navigating the workplace culture. “The key is to remember that informal language here often signals friendliness, not disrespect. When Johnno calls you ‘mate’ or uses casual expressions, he’s trying to make you feel included, even if it has the opposite effect sometimes.”

Zhang nods slowly, beginning to understand. “So when they use these informal expressions…”

“It means they see you as part of the team,” Sunil finishes. “Though I did have to tell Johnno that ‘bowl of rice’ wasn’t the most culturally sensitive way to relate to Asian colleagues,” he adds with a wry smile.

The technical problem solved, Zhang returns to his desk with more than just a working circuit diagram. He has gained a valuable ally in Sunil and a better understanding of how to navigate the complex intersection of technical work and Australian workplace culture.

Working Relationships: The Key to Person-Environment-Fit

Building positive working relationships in professional settings extends far beyond simple collegiality: it fundamentally influences our sense of belonging, job satisfaction, and career success through what organisational psychologists call “person-environment fit.” This concept suggests that our professional effectiveness and wellbeing depend not just on our technical capabilities, but on how well we align with our workplace’s social environment, values, and cultural norms. When we experience strong person-environment fit, we’re more likely to receive mentoring opportunities, be included in informal knowledge sharing, and gain access to the kind of tacit organisational knowledge that proves invaluable for career advancement.

For those who feel like cultural outsiders, whether due to linguistic differences, cultural background, or being new to a profession, developing this fit might initially seem daunting. However, research consistently shows that person-environment fit isn’t static, it’s something we can actively develop through intentional relationship building, cultural learning, and open communication. Understanding this dynamic nature of workplace fit helps us approach relationship building not as a fixed challenge to overcome, but as an ongoing process of professional growth where each interaction, even those that feel awkward or uncertain, contributes to our developing sense of workplace belonging and professional identity.

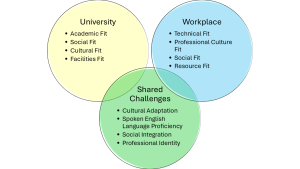

International students face unique challenges with person-environment fit as they enter university life, particularly because they must navigate multiple types of alignment simultaneously. Unlike domestic students who primarily focus on academic adjustment, international students must achieve fit across academic, cultural, social, and physical dimensions, all while operating in a new language and cultural context. Research shows this complex adjustment process significantly impacts their psychological wellbeing, especially when there are misalignments between their goals and expectations and the university environment.

These fit challenges materialise in various ways throughout their university experience. Academically, students might struggle to adapt to different teaching styles or assessment expectations, while culturally, they may find it difficult to understand unwritten social norms or classroom participation expectations. For example, a student might be academically capable but find themselves struggling to engage in tutorial discussions due to language barriers or cultural differences in classroom interaction styles. These challenges are further complicated when students cannot easily access or effectively utilise university support services, either because they don’t understand how to navigate these systems or because the services themselves don’t align with their cultural expectations of support. Understanding these multiple dimensions of fit helps explain why some highly capable international students still struggle to thrive in their new university environment, even when they possess strong academic abilities.

Person-environment fit forms the foundation of workplace satisfaction and success, with working relationships serving as the crucial bridge between individual characteristics and organisational culture. Even when someone’s skills and values align perfectly with their organisation’s mission and requirements, the quality of their daily interactions with colleagues, supervisors, and stakeholders ultimately determines whether they thrive in that environment. These relationships act as the practical manifestation of organisational culture, translating abstract concepts like “collaborative environment” or “innovation-focused culture” into tangible experiences through everyday interactions, shared problem-solving, and mutual support. When professionals develop positive working relationships, they create informal networks that help them navigate organisational complexities, access resources and opportunities, and receive the emotional and practical support needed to overcome workplace challenges. These relationships become particularly vital during periods of change or stress, as they provide the psychological safety necessary for individuals to take risks, share ideas, and maintain resilience in the face of setbacks.

Research by Rose et al. (2021) reveals fascinating insights about how workplace relationships influence intern-to-employee conversion through person-environment fit. The path analysis demonstrates that while both supervisor and coworker relationships matter, coworker relationships have a stronger influence on whether interns are ultimately offered permanent positions.

Let’s break down the key findings from their path analysis: The research showed that coworker relationships had a path coefficient of 0.48 to person-environment fit, whilst supervisor relationships had a lower coefficient of 0.29. This means that positive relationships with colleagues were almost twice as influential in determining how well interns felt they “fitted” within the organisation compared to relationships with supervisors.

This makes intuitive sense when considering the daily reality of internships. While supervisors provide important guidance and feedback, it’s often colleagues who give interns the most complete picture of organisational culture, unwritten norms, and what it’s truly like to work there. Coworkers tend to have more frequent, informal interactions with interns and often feel more approachable for questions about day-to-day work life. These regular interactions help interns determine whether they can envision themselves as permanent members of the organisation.

The research also revealed that person-environment fit strongly predicted conversion intentions, with a path coefficient of 0.52. This suggests that when interns develop positive relationships with colleagues and come to feel they belong in the organisational culture, they become much more likely to accept permanent positions if offered. The effect is compounded: strong coworker relationships enhance person-environment fit, which in turn increases the likelihood of conversion to ongoing employment.

For interns, these findings emphasise that while impressing their supervisor is important, investing time in building authentic connections with colleagues may be even more crucial for long-term career success. Simple actions like joining colleagues for lunch, participating in informal team discussions, and seeking advice from coworkers can significantly impact whether interns feel “at home” in an organisation and ultimately transition from intern to employee.

The research provides strong empirical support for treating internships not just as extended job interviews with supervisors, but as opportunities to become genuinely integrated into the organisational community through peer relationships. For organisations, it suggests that fostering strong intern-coworker bonds may be one of the most effective strategies for converting high-performing interns into valuable permanent employees.

Activity 7.1: Mapping Your Workplace Network

This activity helps interns understand and strengthen their workplace relationships, drawing on Rose et al.’s (2021) research about the crucial role of colleague interactions in person-environment fit.

Part 1: Network reflection

Create a detailed map of your workplace relationships. Draw yourself in the centre of a page, then add:

Part 2: Relationship analysis

Review your network map and write brief notes addressing:

- Balance assessment

- What is the ratio between supervisor and colleague interactions?

- Are your strongest connections mainly with other interns or with experienced staff?

- Which departments or teams are represented in your network?

- Quality evaluation

- Which relationships help you understand the organisation’s values?

- Who gives you insight into the workplace culture?

- Which connections make you feel more integrated into the team?

Part 3: Strategic development

Based on Rose et al.’s (2021) findings about the importance of colleague relationships, create an action plan to strengthen your workplace network:

Identify three colleagues you’d like to develop stronger professional relationships with.

- For each person, plan:

- a work-related topic you could discuss with them

- a specific question about their role or experience

- an opportunity for natural interaction (e.g., shared projects, lunch breaks).

- Set specific, measurable goals such as:

- having two meaningful professional conversations each week

- learning about a different department each month

- contributing to team discussions in meetings.

Part 4: Reflection questions

Consider how your planned interactions might influence your person-environment fit:

- How might stronger colleague relationships help you understand:

- the organisation’s unwritten rules?

- team dynamics and communication styles?

- career development opportunities?

What aspects of organisational culture would you like to learn more about through these relationships?

- How could expanded workplace connections influence your:

- professional development?

- understanding of the organisation?

- likelihood of seeking permanent employment?

💡Remember

Rose et al.’s (2021) research demonstrates that colleague relationships have nearly twice the impact on person-environment fit compared to supervisor relationships. This activity helps interns develop the professional networks that research shows are crucial for successful intern-to-employee conversion.

Professional Duality: Creating a Work Persona

The concept of professional duality, how we develop and maintain distinct personal and professional identities, plays a crucial role in workplace success. Understanding how to navigate this duality helps interns develop authentic yet professionally appropriate workplace behaviours that align with organisational expectations whilst remaining true to their core values.

Having a slightly different personality at work, what we call a “work persona”, is a normal and helpful way to adapt to the professional environment. Research by Chung et al. (2023) looked at 300 employees and found that people naturally develop a work style that combines their organisation’s values with the informal social rules of their workplace. This helps them fit in while still being themselves.

The study shows that we tend to act somewhat differently depending on who we’re talking to at work. With managers and supervisors, we often show a more formal, professional side that matches what the organisation expects. But with our colleagues at the same level, we usually blend our professional and personal sides more naturally. This isn’t about being fake, it’s about knowing how to communicate effectively in different work situations. When people can adjust their style this way, they usually feel more connected to their organisation and more satisfied with their job.

It’s important to understand that having a work persona doesn’t mean you’re pretending to be someone else. Instead, think of it like choosing appropriate clothes for work, you’re still yourself, just dressed for the professional environment. The research found that people who develop a comfortable work style tend to build better relationships at work and do better in their careers. Just as we might act differently at a family dinner compared to a night out with friends, it’s natural and healthy to have a slightly different way of presenting ourselves at work.

The relationship between our work persona and person-environment fit helps us understand how we become part of an organisation’s culture. When we join a workplace, we naturally begin to absorb both the written and unwritten rules of how things work. These unwritten rules, like how people communicate, how they handle disagreements, or what behaviour gets rewarded, often matter more than the official values posted on office walls.

As we develop our work persona, we start to incorporate these organisational values into how we act at work. For example, if an organisation values open communication but expects people to challenge ideas privately rather than in meetings, we learn to adapt our communication style accordingly. This isn’t about changing who we are fundamentally, it’s about understanding and working effectively within the organisation’s culture. The research by Chung et al. (2023) shows that this adaptation helps us form stronger connections with both colleagues and supervisors.

These workplace relationships then reinforce our understanding of the organisation’s values and help us fit in better. Through daily interactions with colleagues and feedback from supervisors, we continuously refine our work persona to better align with the workplace culture. What makes this process particularly interesting is how it creates a cycle: our work persona helps us build relationships, and these relationships in turn help us better understand and adapt to the organisation’s culture. This cycle explains why people often feel more comfortable and natural in their work persona over time, as they develop a deeper understanding of their workplace’s unwritten rules and values.

Activity 7.2: Mapping Your Work Values

This short reflective activity helps interns understand how their work persona develops in response to organisational values and culture.

Think about your workplace and note down your observations about:

The Written Rules

Write down two or three official organisational values or rules from your workplace. For example, these might be values displayed on walls or mentioned in company materials.

The Unwritten Rules

Now think about how people actually work together. Write down two or three unwritten rules you’ve noticed. For example:

- How do people typically handle disagreements?

- When do people tend to speak up in meetings?

- How do colleagues communicate with supervisors?

Your Adaptation

Reflect on how you’ve adjusted your behaviour to fit these unwritten rules. Write down:

- one way you act differently at work compared to outside work

- how this adjustment has helped you build workplace relationships

- whether this change feels natural or forced.

💡Remember

There are no right or wrong answers. The goal is to understand how you naturally adapt to your workplace culture while maintaining your authentic self. This awareness can help you develop more effective workplace relationships.

Trust, Enjoyment and Unspoken Boundaries in Workplace Relationships

The relationship between duality and trust in professional settings represents one of the most nuanced aspects of workplace dynamics. While we naturally seek genuine connections with our colleagues, we must simultaneously maintain appropriate professional boundaries, a balance that directly impacts the development of trust. This duality manifests in how we share personal information while preserving privacy, how we build friendships while maintaining professional objectivity, and how we navigate the complex territory between being approachable and maintaining authority. Understanding this delicate balance proves crucial because trust emerges not from completely removing these boundaries, but from managing them thoughtfully and consistently. When we demonstrate both genuine care for our colleagues and respect for professional limitations, we create an environment where trust can flourish naturally. This careful navigation of personal and professional spaces allows us to build authentic workplace relationships while maintaining the structure and boundaries necessary for effective professional collaboration.

Trust in professional settings emerges from a complex interplay of individual, organisational, and cultural factors that shape how we perceive and evaluate trustworthiness. Research across multiple societies reveals that professional trust operates through two fundamental dimensions, warmth and competence, which manifest differently depending on organisational roles and cultural contexts (Kwantes & Kartolo, 2021; Wöhrle et al., 2015). When colleagues demonstrate both technical capability and genuine concern for others’ wellbeing, they create the foundations for trust to develop. However, this trust must be carefully cultivated within the established norms and expectations that govern professional relationships.

The development of professional trust requires a sophisticated understanding of how different workplace roles shape trust dynamics. Supervisors and colleagues face distinct expectations regarding how they should demonstrate trustworthiness, with most cultures placing greater emphasis on competence for those in leadership positions (Wöhrle et al., 2015). Yet this competence must be balanced with appropriate displays of warmth and concern for others, what researchers term “benevolence”, to build sustainable trust. The challenge lies in calibrating these demonstrations of capability and care to align with both organisational needs and cultural expectations about professional behaviour.

Modern workplace relationships have grown increasingly complex as organisations become more globally connected and culturally diverse. Trust must now be built and maintained across cultural boundaries, often in virtual or hybrid environments where traditional trust-building mechanisms may be limited. This evolution demands a more nuanced approach to professional trust, one that acknowledges how cultural values and practices influence perceptions of trustworthiness while remaining sensitive to the universal human need for both competence and warmth in professional relationships (Kwantes & Kartolo, 2021). Success in this environment requires developing what researchers call “swift trust”, the ability to quickly establish functional trust based on role expectations while remaining open to deeper trust development over time.

During your internship, you’ll need to quickly establish working relationships with supervisors and colleagues despite having limited time to build trust naturally. This is where ‘swift trust’ becomes crucial. It’s a practical form of professional trust that develops rapidly based on roles and initial impressions rather than long-term experience. When you first join your workplace, people will form swift trust assessments of your trustworthiness based on how well you demonstrate both competence in your role and warmth in your interactions. Similarly, you’ll need to make quick judgments about trusting your new colleagues based on their professional roles and early interactions. Understanding swift trust can help you navigate these early workplace relationships more effectively. You can actively demonstrate your reliability through consistent performance while also showing appropriate warmth and collegiality in your interactions. Remember that while swift trust helps establish initial working relationships, it serves as a foundation for developing deeper professional trust over the course of your internship through continued positive interactions and demonstrated reliability. By being mindful of how you present both your capabilities and your interpersonal approach from day one, you can help foster the swift trust necessary for productive workplace relationships.

Trust and enjoyment in the workplace share a fascinating reciprocal relationship. When employees feel they can trust their colleagues and supervisors, they experience greater psychological safety, which allows them to relax and express themselves more authentically at work. This emotional security creates space for spontaneous moments of connection, shared laughter, and genuine camaraderie. Conversely, in environments where trust is lacking, people tend to maintain rigid professional personas, carefully monitoring their words and actions, which inhibits the natural development of enjoyable workplace relationships. Research consistently shows that teams with high levels of trust not only perform better but also report higher job satisfaction and engagement, largely because they feel comfortable enough to share jokes, celebrate successes together, and support each other through challenges. This comfortable atmosphere, built on a foundation of trust, transforms daily work interactions from mere professional obligations into opportunities for meaningful connection and enjoyment.

Research from Mak et al. (2012) shows that workplace relationships and psychological safety are deeply intertwined with the appropriate use of humour, particularly during internships and early career transitions. Just as social bonds often form through shared laughter and jokes, professional relationships tend to develop when colleagues can relax and engage in appropriate workplace banter. However, navigating humour as a new employee requires careful attention to workplace norms and power dynamics.

For interns and new employees, understanding the role of humour in workplace culture presents both opportunities and potential pitfalls. While established employees may engage in more casual or edgy humour based on their longstanding relationships, interns should maintain a more conservative approach until they better understand the specific workplace culture. The most successful interns typically focus first on demonstrating competence and reliability while carefully observing how humour is used by others in the organisation.

Rather than trying to match the joking style of longtime employees, you can build positive relationships by appreciating others’ appropriate humour and occasionally contributing light, professionally safe comments. This measured approach allows you to participate in workplace camaraderie while avoiding potential missteps that could damage their professional reputation. As relationships develop naturally over time, the boundaries of appropriate humour may expand, but this should happen gradually and organically rather than being forced.

Rather than trying to match the joking style of longtime employees, you can build positive relationships by appreciating others’ appropriate humour and occasionally contributing light, professionally safe comments. This measured approach allows you to participate in workplace camaraderie while avoiding potential missteps that could damage their professional reputation. As relationships develop naturally over time, the boundaries of appropriate humour may expand, but this should happen gradually and organically rather than being forced.

A crucial reminder: While humour and playful banter can build positive workplace relationships, jokes should never come at your expense or make you feel targeted, uncomfortable, or unsafe. Professional humour builds people up rather than tears them down. If you experience bullying, harassment, or discriminatory behaviour disguised as “jokes,” this is unacceptable in any workplace. Your university’s placement coordinator is there to support you. Don’t hesitate to reach out to them if you feel unsafe or singled out. You can also access support through your university’s counselling services and student advocacy teams. Remember that reporting inappropriate behaviour helps protect both yourself and future interns who might face similar situations. Your wellbeing and professional development should always be the priority during your internship experience.

Activity 7.3: Understanding Trust and Humour in Professional Setting

Part 1: Reflection exercise

Using the DIEP (Describe, Interpret, Evaluate, Plan) model, reflect on a time when you were new to a professional or academic group and had to navigate social dynamics, particularly around humour and trust.

💡Remember

The goal of this reflection is not just to recall past experiences, but to develop a thoughtful, professional approach to workplace relationships that will serve you throughout your career. Consider sharing your insights with your peers to learn from their experiences as well.

Part 2: Scenario analysis

Read the following scenario carefully:

Sarah has been interning at an engineering firm for three weeks. She notices that her team often makes playful jokes about their manager Tom’s intense coffee addiction, and he good-naturedly joins in these jokes himself. During a team meeting, Sarah attempts to participate by commenting, “Watch out, everyone, Tom hasn’t had his hourly coffee yet!” However, the room falls silent, and several colleagues look uncomfortable. Later, a senior colleague explains that while the team does joke about Tom’s coffee habits, only his direct reports who’ve known him for years participate in this banter.

Working with a partner, discuss:

- What assumptions did Sarah make about workplace relationships?

- How could she have better understood the unwritten rules about humour in this workplace?

- What would be more appropriate ways for Sarah to begin building rapport with her team?

- How might Sarah recover professionally from this misstep?

Remember to consider both trust and humour when analysing this scenario. The goal isn’t to discourage participation in workplace camaraderie, but to understand how to navigate it appropriately as a newcomer.

When Trust Is Broken

Despite our best efforts to build positive workplace relationships, sometimes interactions can sour or trust can be damaged. Even the most carefully navigated professional relationships may encounter difficulties, whether through misunderstandings, cultural differences, or genuine conflicts. The skills required to repair workplace relationships draw on many of the same fundamentals we’ve discussed, emotional intelligence, cultural awareness, and professional judgment, but require us to apply them in more challenging circumstances. What matters most isn’t that we never experience conflict, but rather how we handle these situations when they arise. The mark of a true professional isn’t avoiding all interpersonal challenges, but addressing them with maturity, self-awareness, and a commitment to positive resolution.

Workplace friendships, while potentially valuable for both job satisfaction and professional development, can be particularly fragile and subject to various forms of deterioration. Research by Sias et. al. (2004) identified several key triggers that commonly lead to the breakdown of workplace relationships, including betrayals of trust, violations of organisational values, and changes in professional status through promotion. These deterioration factors are especially impactful because they challenge the delicate balance between professional obligations and personal connections that workplace friendships must maintain.

The complexity of workplace friendship deterioration lies in its often unavoidable nature, particularly when organisational changes occur. For instance, when one friend is promoted to a supervisory position over another, the fundamental dynamics of their relationship must shift to accommodate new power structures and professional responsibilities. This transition can create tension between maintaining personal rapport and upholding professional boundaries. Similarly, extended absences from work, whether through leave, transfers, or other circumstances, can strain these relationships as the regular contact and shared experiences that help maintain workplace friendships are disrupted.

What makes workplace friendship deterioration particularly challenging is that traditional friendship repair strategies often prove ineffective in the professional context. Unlike personal friendships outside of work, workplace relationships must continue to function at some level even after deterioration occurs, as colleagues typically need to maintain professional interactions. Sias et. al’s (2004) research demonstrated that attempts to resolve these friendship breakdowns were largely unsuccessful, suggesting that once certain professional boundaries or trust levels are breached, the unique combination of personal and professional expectations that characterise workplace friendships becomes difficult to rebuild. This understanding highlights the importance of maintaining clear boundaries and managing expectations in workplace friendships from the outset.

What makes workplace friendship deterioration particularly challenging is that traditional friendship repair strategies often prove ineffective in the professional context. Unlike personal friendships outside of work, workplace relationships must continue to function at some level even after deterioration occurs, as colleagues typically need to maintain professional interactions. Sias et. al’s (2004) research demonstrated that attempts to resolve these friendship breakdowns were largely unsuccessful, suggesting that once certain professional boundaries or trust levels are breached, the unique combination of personal and professional expectations that characterise workplace friendships becomes difficult to rebuild. This understanding highlights the importance of maintaining clear boundaries and managing expectations in workplace friendships from the outset.

Activity 7.4: A Tricky Situation

Jenna is coordinating environmental impact assessments for Blue Ocean Dive, a well-established diving operator in the Cairns region. The company is considering expanding their operations to include Cowboys Reef, a more remote and pristine area of the Great Barrier Reef. While this expansion could significantly boost profits, it also raises important environmental considerations given the reef’s relatively untouched state.

Following the weekly operations meeting, Marcus approaches Jenna privately. He expresses serious concerns about Isabella, one of the marine scientists conducting the environmental impact studies. Marcus claims that Isabella seems to be downplaying the potential environmental risks in her preliminary reports, particularly regarding the impact of increased boat traffic on the reef’s delicate ecosystem. He tells Jenna that during a recent site visit, he overheard Isabella telling another staff member that “more cancelled trips due to weather would mean more paid days off for the dive masters.” Marcus couldn’t provide concrete evidence but insists that Isabella’s personal benefit might be influencing her scientific assessment.

That same afternoon, Jenna and Isabella are having coffee together, as they often do. During their conversation, Isabella appears visibly upset and confides in Jenna about a recent personal situation. She had gone on several dates with Marcus, but their last encounter ended terribly. Isabella mentions that Marcus accused her of being “too stuck up” and not “open-minded enough”.

The situation presents Jenna with a complex dilemma. The environmental impact assessment is crucial for both the company’s future and the reef’s protection. Should she take Marcus’s allegations seriously and launch a formal investigation into Isabella’s methodology and data analysis? This could potentially damage both professional relationships and the project’s timeline. Alternatively, should she interpret Marcus’s claims as potentially biased by their failed romantic connection? Yet ignoring his concerns entirely could mean overlooking genuine issues with the assessment’s integrity.

What steps should Jenna take to handle this situation professionally while ensuring both the integrity of the environmental assessment and the maintenance of a healthy workplace environment?

Part 1: Individual reflection

After reading the scenario carefully, consider the following questions:

- What are the key professional and personal relationships at play in this situation?

- How might different types of workplace trust (professional, emotional, ethical) be affected?

- If you were Jenna, what aspects of this situation would concern you most from:

- a project integrity perspective

- a team dynamics perspective

- a professional ethics perspective.

Write a brief reflection addressing these points, considering how the concepts of workplace trust and relationship boundaries we’ve discussed apply to this scenario.

Part 2: Small group discussion

In groups of 3-4, discuss the potential consequences of each possible course of action Jenna might take:

- investigating Isabella’s work formally

- dismissing Marcus’s concerns

- seeking a middle-ground approach

- how might this situation affect:

- the team’s professional dynamics

- future workplace relationships

- the credibility of the environmental assessment.

Develop a specific action plan for Jenna that addresses both the professional and interpersonal aspects of this situation.

Part 3: Professional communication exercise

Draft two professional emails that Jenna might need to write:

- a follow-up email to Marcus acknowledging his concerns while maintaining professional boundaries

- an email to her supervisor explaining the situation and her proposed course of action.

Remember to consider:

- appropriate professional tone

- clear documentation of concerns

- protection of all parties’ professional integrity

- maintenance of appropriate confidentiality.

Part 4: Discussion and debrief

Share key insights from your group discussions, focusing on:

- how workplace relationships can affect professional judgment

- strategies for maintaining professional boundaries

- best practices for handling conflicts between personal and professional relationships

- ways to protect project integrity while managing interpersonal dynamics.

Extension activity

Consider how this situation might be different if:

- the relationship breakdown had occurred after the allegations

- multiple team members had raised similar concerns

- the environmental assessment had already been completed.

How would these variations affect the appropriate professional response?

💡Remember

The goal is not to judge the personal choices of any party involved, but to understand how to maintain professional integrity and workplace trust when personal and professional boundaries become blurred.

Key Takeaways

In this chapter, we covered:

- the crucial role of person-environment fit in workplace success, with research showing that positive coworker relationships have nearly twice the impact on successful internship outcomes compared to supervisor relationships, highlighting the importance of building authentic connections with colleagues at all levels

- how developing an effective professional work persona allows us to adapt to workplace culture while maintaining authenticity, enabling us to build trust and navigate organisational dynamics successfully without compromising our core values

- the intricate balance between trust and professional boundaries in workplace relationships, including how to develop “swift trust” early in internships while maintaining appropriate professional distance and navigating cultural differences

- the complex role of workplace humour and enjoyment in building positive professional relationships, with research demonstrating that successful interns carefully observe existing workplace dynamics before participating in casual banter or jokes

- strategic approaches for handling workplace relationship challenges, including how to maintain professionalism when trust is damaged, navigate conflict between personal and professional relationships, and rebuild productive working relationships after difficulties arise.

References

Chung, K., Park, J. S., & Han, S. (2023). Effects of workplace relationships among organizational members on organizational identification and affective commitment: Nuanced differences resulting from supervisor vs. colleague relationship. Current Psychology, 43. 12335–12353. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-05314-5

Kwantes, C. T., & Kartolo, A. B. (2021). A 10 nation exploration of trustworthiness in the workplace. Interpersona: An International Journal on Personal Relationships, 15(2), 146–166. https://doi.org/10.5964/ijpr.5639

Mak, B. C. N., Liu, Y., & Deneen, C. C. (2012). Humor in the workplace: A regulating and coping mechanism in socialization. Discourse & Communication, 6(2), 163–179. https://doi.org/10.1177/1750481312437445

Rose, P. S., Teo, S. T. T, Nguyen, D., & Nguyen, N. P. (2021). Intern to employee conversion via person–organization fit. Education & Training, 63(5), 793–807. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-08-2020-0225

Sias, P. M., Heath, R. G., Perry, T., Silva, D., & Fix, B. (2004). Narratives of workplace friendship deterioration. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 21(3), 321–340. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407504042835

Wöhrle, J., van Oudenhoven, J. P., Otten, S., & van der Zee, K. I. (2015). Personality characteristics and workplace trust of majority and minority employees in the Netherlands. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 24(2), 161–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2014.891583

Media Attributions

- Man in blue shirt using computer © Firosnv. Photography, available under an Unsplash licence

- Shared dimensions of university and workplace cultural fits © Ben Archer is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- A group of people eating pizza in an office © Thirdman, available under a Pexels licence

- A group of people stacking hands while holding takeout boxes © Mikhail Nilov, available under a Pexels licence

- Photo of Women Laughing © RF._.studio, available under a Pexels licence

- Close-up of a Sad Woman © Photo By: Kaboompics.com, available under an Unsplash licence

- An Angry Boss during a Meeting © Antoni Shkraba, available under a Pexels licence