Creative Commons powers the open education movement with tools that help create better, more flexible and sustainable open educational resources (OER), practices, and policies.

Creative Commons powers the open education movement with tools that help create better, more flexible and sustainable open educational resources (OER), practices, and policies.

Creative Commons licences are the most popular open licences among education projects around the world. This chapter will introduce you to the specifics of using CC licences and CC licensed content for education purposes.

This chapter has three sections:

There are also additional resources below if you are interested in learning more about any of the topics covered in this chapter. Likewise, you may be interested in reading Chapter 6 CC for Open Scholarly Publishing.

Open education is an idea, as well as a set of content, practices, policy, and community which, properly leveraged, can help everyone in the world access free, effective, open learning materials for the marginal cost of zero. For the first time in history, educators around the world can create, open, and share high quality, effective learning materials with everyone who wants to learn. The key to this transformational shift in learning is Open Educational Resources (OER). OER are education materials that are shared at no cost with legal permissions for the public to freely use, share, and build upon the content.

OER are possible because:

Because we can share effective education materials with the world for near zero cost, many people argue that educators and governments who support public education have a moral and ethical obligation to do so. This argument is based on the premise that education is fundamentally about sharing knowledge and ideas. Creative Commons believes OER will replace much of the expensive, proprietary content used in academic courses. Shifting to this model will generate more equitable economic opportunities and social benefits globally without sacrificing the quality of education content.

Learning Outcomes

Big Question/Why It Matters

Does it seem reasonable that education in the age of the internet should be more expensive and less flexible than it was in previous generations? As people and knowledge are increasingly networked and available online, what will it mean for learning, work, and society?

Formal education, even in the age of the internet, can be more expensive and less flexible than ever. In many countries, publishers of education materials overcharge for textbooks and other resources. As part of their transition from print to digital, these same companies have largely moved away from a model where learners purchase and own books to a “streaming” model where they have access for a limited time.

Further, publishers are constantly developing restrictive technologies that limit what learners and faculty can do with the resources they have temporary access to, including inventing novel ways to prohibit printing, prevent cutting and pasting, and restrict the sharing of materials between friends.

Personal Reflection/Why it Matters To You

To begin, watch this video [3:14]:

Open Educational Resources (OER) are teaching, learning and research materials in any medium that reside in the public domain or are released under an open licence that permits no-cost access, use, adaptation and redistribution by others.

Or you could use this less technical definition to describe OER to someone:

OER are education materials that can be freely downloaded, edited, and shared to serve all students better.[2]

In contrast to traditional education materials, which are constantly becoming more expensive and less flexible, OER provide everyone, everywhere, free permission to download, edit, and share them with others. David Wiley provides another popular definition, stating that only education materials licensed in a manner that provide the public with permission to engage in the 5R activities can be considered OER.

The 5Rs include:

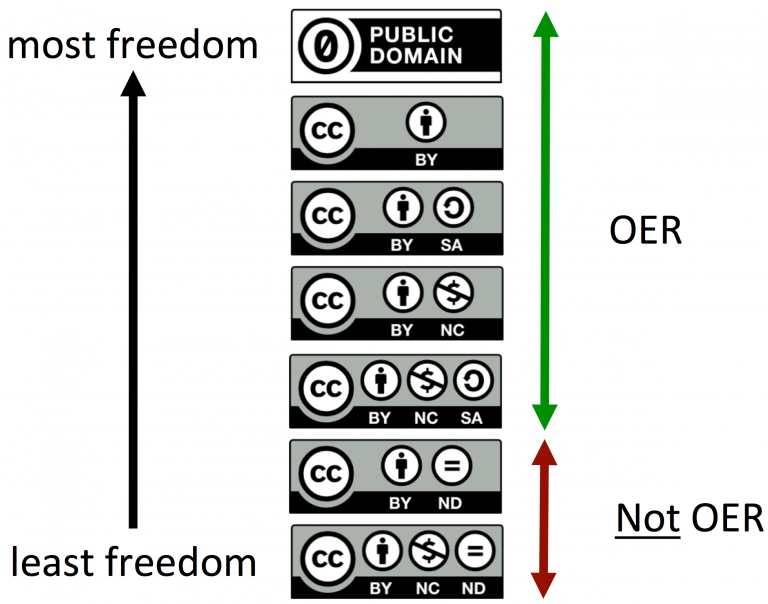

The easiest way to confirm that an education resource is an open education resource that provides you with the 5R permissions is to determine that the resource is either in the public domain or has been licensed under a Creative Commons licence that permits the creation of derivative works: CC BY, CC BY-SA, CC BY-NC, or CC BY-NC-SA.

OER come in all shapes and sizes. A piece of OER can be as small as a single video or simulation, and can be as large as an entire degree program. It can be difficult, or at least time-consuming for teachers to assemble OER into a collection comprehensive enough to replace an all rights reserved copyright textbook. For this reason, OER are often collected and presented in ways that resemble a traditional textbook in order to make them easier for instructors to understand and adopt.

The term “open textbook” simply means an OER in “book” (or eBook) form or a collection of OER that have been organised to look like a traditional textbook in order to ease the adoption process. To see examples of open textbooks in a number of disciplines, visit:

In addition to demonstrating that students save money when their teachers adopt OER, research shows that learners can have better outcomes when their teachers choose OER instead of education materials available under all rights reserved copyright.

The idea of OER is strongly advocated by a broad range of individuals, organisations, and governments, as evidenced by documents like the UNESCO Paris OER Declaration (2012), UNESCO Ljubljana OER Action Plan (2017), and the UNESCO OER Recommendation (2019). In Australia for example, Queensland University of Technology has an OER policy, and other institutions are discussing creating similar policies.

Teaching staff typically use a mix of all-rights-reserved commercial content, library resources, and OER in their courses. While the library resources are “free” to the learners and faculty at that institution, they are (a) not “free” as the institution library has to pay to purchase or subscribe to them, and (b) not available to anyone outside of the institution.

Openly licensing learning materials enables educators to use the materials more effectively, which can lead to better learning and student outcomes. OER can be remixed and adapted: updated, tailored and improved locally to fit the needs of learners—translating the OER into a local language, adapting a biology open textbook to align it with local science standards, or modifying an OER simulation to make it accessible for a student who cannot hear.

The ideas of remix and adaptation are fundamental to education. Creative reuse of materials created by other educators and authors is about more than just seeking inspiration; we copy, adapt, and combine different materials to craft education resources for our learners.

Incorporating materials created by others and combining materials from different sources can be tricky, not only from a pedagogical perspective, but also from a copyright perspective.

Online digital education resources have different legal permissions that empower (or not) the public to use, remix and share those resources. Here are a few of those legal categories:

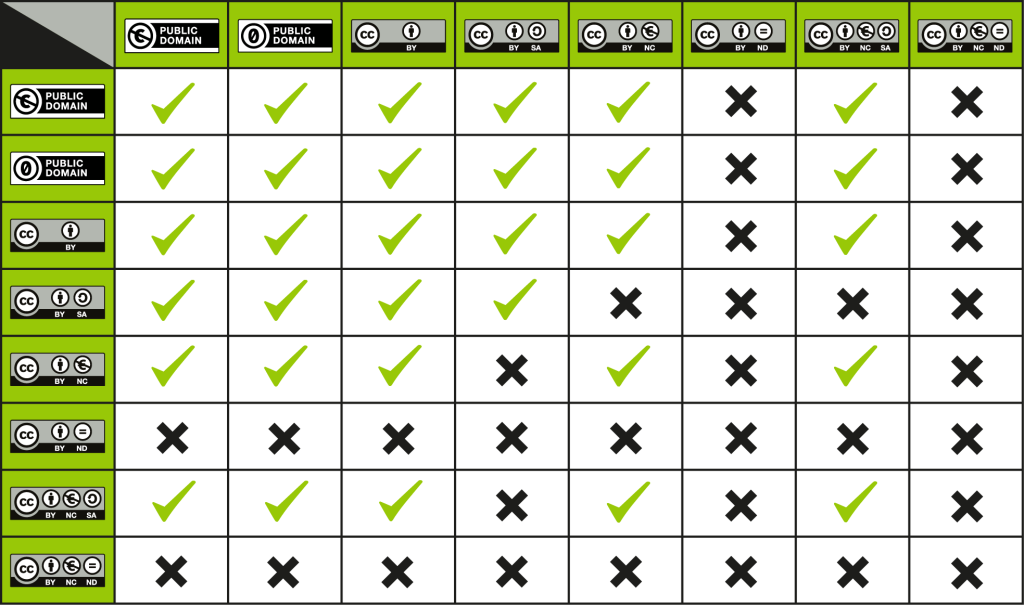

If you want to know which CC licensed works can be remixed with other CC licensed works, revisit the CC Remix Chart we studied in Section 4.4. Where there is a green check at the intersection of two CC licensed works, you can remix those two works. Where you see a black X, you cannot remix those two CC licensed works.

5.1 Final remarks

Much of this chapter focuses on how to create openly licensed materials, by sharing the legal perspective and the practical steps needed. In this section, we explore how to create OER so they can have the biggest impact and be used without any legal or technical barriers.

Learning Outcomes

Big Question/Why It Matters

A big part of any educator’s work is preparing, updating, and combining learning materials. Making those materials open requires just a few additional steps, and it’s easier than you think. What are those steps? What should you consider and expect when you want to create and publish your resources in the open?

When we share our education resources as OER, we share our best practices, our expertise, our challenges and solutions. Education is about sharing. When we share our work with more people – we become better educators.

Personal Reflection/Why it Matters To You

Because educators and librarians can share OER with everyone for near zero cost,[3] we should. After all, education is fundamentally about sharing knowledge and ideas. Libraries are about archiving, sharing and helping learners find the knowledge they seek. When we CC license our work, we are sharing that work with the public under simple, legal permissions. Sharing your work is a gift to the world.

Creative Commons has a suite of six open copyright licences—and fully support authors’ selection and use of any of the CC licences or public domain tools. However, not all education materials available under a CC licence are OER. Review this chart that details which CC licences work well for education resources and which do not.

The two CC NoDerivatives (ND) licences are not OER-compatible licences because they do not allow the public to revise or remix the education resource. Because the ND licences do not meet the 5Rs or any of the major OER definitions, the open education movement does not consider ND-licensed education resources “OER.”

Choosing the right licence for your OER requires you to think about which permissions you want to give to other users—and which permissions you want to retain for yourself. For basic information about the licences, how to choose and apply one to your work or combined works from other people and sources, revisit Section 4.1.

Other than choosing the right CC licence, what other aspects of openness and pedagogy are worth considering? Here is a list of best practices to include in your work when building OER.

At its core, OER is about making sure everyone has access. Not just rich people, not just people who can see or hear, not just people who can read English, not just people who have digital devices with access to high-speed internet—everyone.

As authors and institutions build and share OER, best practices in accessibility need to be part of the instructional and technical design from the start. Educators have legal and ethical responsibilities to ensure our learning resources are fully accessible to all learners, including those with disabilities.

Best practices to ensure your OER is accessible to all include:

Final remarks

Openness in education brings the potential for co-creation and learning through active participation in how knowledge is produced.

Learning Outcomes

Big Question/Why It Matters

Many educators have a problem with OER. They’ve spent so long using education materials published under restrictive licenses that they struggle to take advantage of the new pedagogical capabilities offered by OER. These pedagogical capabilities are all about the teaching and learning practice and tools that empower learners and teachers to create and share knowledge openly and learn deeply.

Personal Reflection/Why It Matters to You

When you’ve used OER in the past, have you taken advantage of the permissions offered by their open licenses, or did you use OER just like you used your previous, traditionally copyrighted materials? In other words, did you do anything with the OER that was impossible to do with traditionally copyrighted materials? Why or why not?

The open education movement is still discussing and debating what it means to think about teaching and learning practices in a more inclusive, diverse and open manner. Read these examples of how various educators approach this topic. At least three major definitions have emerged from this discussion.

It’s well established that people learn through activity. It’s equally well established that copyright restricts people from engaging in a range of activities. When juxtaposed like this, it becomes clear that copyright restricts pedagogy by contracting the universe of things learners and teachers can do with education materials. If there are things learners aren’t allowed to do, there are ways learners aren’t allowed to learn. If there are things teachers aren’t allowed to do, there are ways teachers aren’t allowed to teach.

One of the foundational ideas of open teaching and learning practices is the distinction between disposable and renewable assignments.

Do you remember doing homework for school that felt utterly pointless? A “disposable assignment” is an assignment that supports an individual student’s learning but adds no other value to the world—the student spends hours working on it, the teacher spends time grading it, and the student gets it back and then throws it away. While disposable assignments may promote learning by an individual student, these assignments can be demoralising for people who want to feel like their work matters beyond the immediate moment.

In contrast, “renewable assignments” both support individual student learning and add value to the broader world. With renewable assignments, learners are asked to create and openly license valuable artefacts that, in addition to supporting their own learning, will be useful to other learners both inside and outside the classroom. For example, classic renewable assignments include collaborating with learners to write new case studies for textbooks, create “explainer” videos, and modify learning materials to speak more directly to learners’ local cultures and needs.

A couple of interesting examples of renewable assignments are a remixed explainer video that a student made about Blogs and Wikis, and the DS106 assignment bank, which is a hub for student-created, CC licensed content. Additional examples are available on the Open Pedagogy website.

Final remarks

Chapter 5 Additional Resources