Creative Commons licences do not replace copyright. They are built on top of it.

The default of “all rights reserved” copyright is that all rights to copy and adapt a work are reserved by the author or creator (with some important exceptions that you will learn about shortly). Creative Commons licences adopt a “some rights reserved” approach, enabling an author or creator to free up their works for reuse by the public under certain conditions. To understand how Creative Commons licences work, it is important that you have a basic understanding of copyright.

This chapter has four sections:

2.2 Global Aspects of Copyright

2.4 Exceptions and Limitations of Copyright

2.1 Copyright Basics

Is copyright confusing to you? Get some clarity by understanding its history and purpose.

Learning Outcomes

- trace the basic history of copyright

- explain the purpose of copyright

- explain how copyright is automatic

- explain general copyright terms

Big Question/Why It Matters

Why do we have laws that restrict the copying and sharing of creative work? How do those laws work in the context of the internet, where nearly everything we do involves making a copy?

Copyright law is an important area of law, one that reaches into nearly every facet of our lives, whether we know it or not. Aspects of our lives that in some instances are not regulated by copyright – like reading a physical book – become regulated by copyright when technology is used to share the same book posted to the internet. Because almost everything we do online involves making a copy, copyright is a regular feature in our lives.

Personal Reflection/Why It Matters to You

Acquiring Essential Knowledge: An Overview

Copyright law is as integral to your daily life as local traffic laws. Copyright law is the area of law that limits how others may use the original works of authors (or creators, as we often call them)—works spanning the spectrum from novels and operas, to cat videos, to scribbles on a napkin.

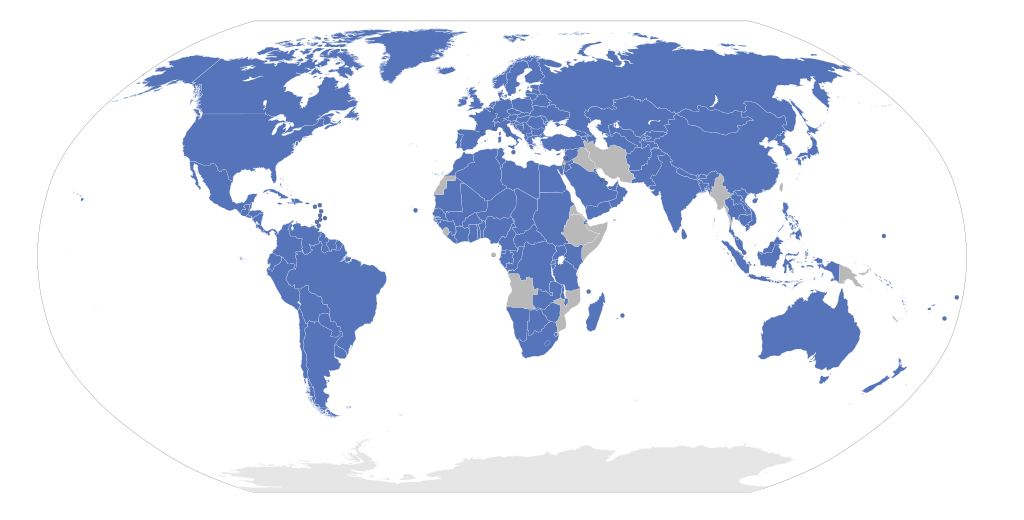

Although copyright laws vary from country to country, there are certain commonalities among copyright laws globally. This is largely due to international treaties. These treaties are explained in detail in section 2.2.

There are some important fundamentals you need to be aware of regarding what is copyrightable, as well as who controls the rights and can grant permission to reuse a copyrighted work.

- Copyright grants a set of exclusive rights to creators, which means that no one else can copy, distribute, perform, adapt, or otherwise use the work in violation of those exclusive rights. This gives creators the means to control the use of their works by others, thereby incentivising them to create new works in the first place. The person who controls the rights, however, may not always be the author. It is important to understand who controls the exclusive rights granted by copyright in order to understand who has authority to grant permissions to others to reuse the work (e.g., adding a CC licence to the work). For example:

- Work created in the course of your employment may be subject to differing degrees of employer ownership based on your jurisdiction. Australia, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States adhere to some form of doctrine commonly known as “work-for-hire.” This doctrine generally provides that if you have created a copyrightable work within the scope of your employment, the employer is the owner of, and controls, the economic rights in the copyrighted work even though you are the author and may retain your moral rights.

- Independent contractors may or may not own and control copyright in the works they create in that capacity—that determination depends on the terms of the contract between you and the organisation that engaged you to perform the work, even though you are the author and may have moral rights.

- Teachers, university faculty, and learners may or may not own and control copyright in the works they create in those capacities—that determination will depend on certain laws (such as work-for-hire in some instances) and on the terms of the employment or contractor agreement, university or school policies, and terms of enrolment at the particular institution, even though they are the creators and may have moral rights.

- For information about JCU’s intellectual property conditions, see Who Owns Copyright at JCU.

- If you have co-created an original work that is subject to copyright, you may be a joint owner, not an exclusive owner, of the rights granted by copyright law. Joint ownership generally allows all owners to exercise the exclusive rights granted by law, but requires the owners to be accountable to one another for certain uses they make of their joint work.

- Ownership and control of rights afforded by copyright laws are complicated. For more information, please see the additional resources.

- Copyright does not protect facts or ideas themselves, only the expression of those facts or ideas. That may sound simple, but unfortunately, it is not. The difference between an idea and the expression of that idea can be tricky, but it’s also extremely important to understand. While copyright law gives creators control over the expression of an idea, it does not allow the copyright holder to own or exclusively control the idea itself.

- As a general rule, copyright is automatic the moment a work is fixed in a tangible medium. For example, you have a copyright as soon as you type the first stanza of your poem or record a song in most countries. Registering your copyright with a local copyright authority allows you to officially record your authorship, and in some countries this may be necessary to enforce your rights or might provide you with certain other advantages. In Australia, registration of your work is not required.

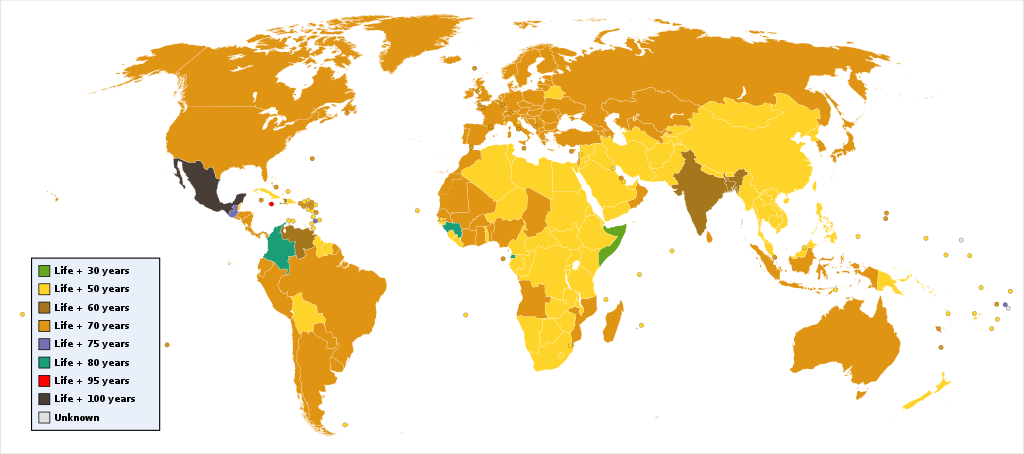

- Copyright protection lasts a long time. More on this later, but for now it’s enough to know that copyright lasts a long time, often many decades after the creator dies.

Note: The combination of very long terms with automatic entry into the copyright system has created a massive amount of so-called “orphan works”—copyrighted works for which the copyright holder is unknown or impossible to locate.

A Simple History of Copyright

Arguably, the world’s most important early copyright law was enacted in 1710 in England: the Statute of Anne, “An act for the encouragement of learning, by vesting the copies of printed books in the authors or purchasers of such copies, during the times therein mentioned.” This law gave book publishers 14 years of legal protection from the copying of their books by others.

Since then, the scope of the exclusive rights granted under copyright has expanded. Today, copyright law extends far beyond books, to cover nearly anything with even a fragment of creativity or originality created by humans.

Additionally, the duration of the exclusive rights has also expanded. Today, in many parts of the world, the term of copyright granted to an individual creator is the life of the creator plus an additional 50 years. See the “Worldwide map of copyright term length” reproduced in Section 2.2 for more details about the duration of copyright and its variances worldwide.

And finally, since the Statue of Anne, copyright treaties have been signed by many countries. The result is that copyright laws have been harmonised to some degree around the world. You will learn more about the most important treaties and how copyright works around the world in Section 2.2.

Watch Copy (aka copyright) Tells the Story of His Life [9:16] from #FixCopyright for a short history of copyright and its relation to creativity and sharing (CC BY 3.0).

Purpose of Copyright

There are two primary rationales for copyright law, though rationales do vary among legal traditions.

Utilitarian: Under this rationale, copyright is designed to provide an incentive to creators. The aim is to encourage the creation of new works.

Author’s rights: Under this rationale, copyright is primarily intended to ensure attribution for authors and preserve the integrity of creative works. The aim is to recognise and protect the deep connection authors have with their creative works. Learn more about authors’ rights in the additional resources box at the end of the chapter.

While different legal systems identify more strongly with one or the other of these rationales, or have other rationales particular to their legal traditions, many copyright systems are influenced by and draw from both (due, in large part, to historical reasons that are outside the scope of this material). Do one or both of these justifications resonate with you? What other reasons do you believe support or don’t support the granting of exclusive rights to creators of original works?

Drawing on the author’s rights tradition, most countries have moral rights that protect, sometimes indefinitely, the bond between an author and their creative output. Moral rights are distinct from the rights granted to copyright holders to restrict others from economically exploiting their works, but closely connected.

The two most common types of moral rights are the right to be recognised as the author of the work (known traditionally as the “right of paternity”), and the right to protect the work’s integrity (generally, the right to object to distortion of or the introduction of undesired changes to the work).

Not all countries have moral rights, but in some parts of the world they are considered so integral that they cannot be licensed away or waived by creators, and they last indefinitely. Please see additional resources for more information about these important rights. Moral rights were legislated in Australia in 2000. See the Moral Rights fact sheet from the Australian Copyright Council.

How Copyright Works: A Primer

Copyright applies to works of original authorship, which means works that are unique and not a copy of someone else’s work, and most of the time requires fixation in a tangible medium (written down, recorded, saved to your computer, etc.).

Copyright law establishes the basic terms of use that apply automatically to these original works. These terms give the creator or owner of copyright certain exclusive rights while also recognising that users have certain rights to use these works without the need for a licence or permission.

What’s Copyrightable?

In countries that have signed on to the major copyright treaties described in more detail in Section 2.2, copyright exists in the following general categories of works, though sometimes special rules apply on a country-by-country basis. A specific country’s copyright laws almost always further specify types of works within each category. Can you think of a type of work within each category?

- literary and artistic works

- translations, adaptations, arrangements of music and alterations of literary and artistic works

- collections of literary and artistic works.

Additionally, depending on the country, original works of authorship may also include, among others:

- applied art and industrial designs and models

- computer software.

What are the Exclusive Rights Granted?

Creators who have copyright get exclusive rights to control certain uses of their works by others, such as the following (note that other rights may exist depending on the country):

- to make authorised translations of their works

- to make copies of their works

- to publicly perform and communicate their works to the public, including via broadcast

- to make adaptations and arrangements of their works.

This means that if you own the copyright to a particular book, no one else can copy or adapt that book without your permission (with important caveats, which we will get to later in Section 2.4). Keep in mind there is an important difference between being the copyright holder of a novel and controlling how a particular authorised copy of the novel is used. While the copyright owner owns the exclusive rights to make copies of the novel, the person who owns a particular physical copy of the novel, for example, can generally do what they want with it, such as loan it to a friend or sell it to a used bookstore.

One of the exclusive rights of copyright is the right to adapt a work. An adaptation (or a derivative work, as it is sometimes called) is a new work based on a pre-existing work. In some countries, the term “derivative work” is used to describe changes that include but are not limited to “adaptations” as described in the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works, which uses both of these terms in different articles. For the purposes of this course and understanding how CC licences and public domain tools work, the terms “derivative work” and “adaptation” are interchangeable and mean a work that is created from a pre-existing work through changes that can only be made with the permission of the copyright holder. It is important to note that not all changes to an existing work require permission. Generally, a modification rises to the level of an adaptation or derivative when the modified work is based on the prior work and manifests sufficient new creativity to be copyrightable, such as a translation of a novel from one language to another, or the creation of a screenplay based on a novel.

Copyright owners often grant permission to others to adapt their work. Common examples are translations of a work from one language to another, or adapting a novel into a screenplay for a movie. Adaptations are entitled to their own copyright, but that protection only applies to the new elements that are particular to the adaptation. For example, if the author of a poem gives someone permission to make an adaptation, the person may rearrange stanzas, add new stanzas, and change some of the wording, among other things. Generally, the original author retains all copyright in the elements of the poem that remain in the adaptation, and the person adapting the poem has a copyright in their new contributions to the adapted poem. Creating a derivative work does not eliminate the copyright held by the creator of the pre-existing work.

Special Note about Additional Exclusive Rights

There are two other categories of rights that are important to understand because the rights are licensed and referenced by Creative Commons licences and public domain tools.

- Moral Rights

- As mentioned above, moral rights are an integral feature of many countries’ copyright laws. These rights are recognised in Article 6bis of the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works (the “Berne Convention”), described in more detail in Section 2.2, and are integrated in the laws of all treaty signatories to some extent. Creative Commons licences and legal tools account for these rights, and the reality is that they cannot be waived or licensed in many countries even though other exclusive economic rights are waivable or licensable. See Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) Part IX for general description of moral rights in Australia. For resources explaining these important rights in more depth, please see additional resources.

- Similar and Related Rights (including rights known in many countries as “neighbouring rights”)

- Closely related to copyright are similar and related rights. These are rights that relate to copyrighted works and grant additional exclusive rights beyond the basic rights granted authors described above. Some of these rights are governed by international treaties, but they also vary country by country. Generally, these rights are designed to give some “copyright-like” rights to those who are not themselves the author but are involved in communicating the work to the public, for example, such as broadcasters and performers. Some countries like Japan have established these rights as part of copyright itself; other countries treat these rights separately from, though closely related to, copyright.

The term “Similar Rights” is used to describe these rights in CC licences and CC0, as you will learn in Section 3.2.

An in-depth discussion of these rights is beyond the scope of this chapter. What is important to be aware of is that they exist, and that Creative Commons licences and public domain tools cover these rights, thereby allowing those who have such rights to use CC tools to give the public permission to use works in ways that would otherwise violate those rights. Please see additional resources for more information about similar and related rights.

Does the Public have any Right to use Copyrighted Works that do not Violate the Exclusive Rights of Creators?

All countries that have signed on to major international treaties grant the public some rights to use copyrighted works, without permission, without violating the exclusive rights given creators. These are generally called “exceptions and limitations” to copyright. Many countries itemise the specific exceptions and limitations on which the public may rely, while some countries have flexible exceptions and limitations such as the concept of “fair use” in the United States, “fair dealing” in some Commonwealth countries, and education-specific exceptions and limitations in many other parts of the world, including the global south. Exploring these concepts in detail is reserved for Section 2.4. What is important to know is that copyright law does not require permission from the creator for every use of a copyrighted work; some uses are permitted as a matter of copyright policy that balances the sometimes competing interests of the copyright owner and the public.

What Else Should I Know about Copyright?

Copyright is complex and varies around the world. This chapter serves as a general introduction to its central concepts. There are some concepts, such as 1) liability and remedies, 2) licensing and transfer and 3) termination of copyright transfers and licences that you should be aware of because you are likely to encounter them at some point. You will find a comprehensive explanation of these concepts and the other issues raised in this chapter in the additional resources box.

Also, there are additional considerations for some creative works that copyright law does not affect. While extensive discussion of these issues is beyond the scope of this Unit, here are some examples that merit attention:

- Most federal government websites, including legislation, are licensed under CC BY 4.0. See the copyright statements for the Australian Federal Register of Legislation and the Parliament of Australia.

- Queensland legislation on the Office Of Parliamentary Council website is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 International licence.

- Copyright of Queensland Parliament materials on the Queensland Parliament website are subject to all rights reserved as described in the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Other materials on this website are licensed under a CC BY-NC-ND 3.0 unless otherwise noted.

- Cultural and historical contexts and contingencies can influence people’s decisions to use creative works; yet Traditional Knowledge labels, for example, exist outside of the limits of copyright. Traditional Knowledge Labels offer identifiers for creative works, recognising their cultural heritage and significance to the communities from where the works originated.

- According to Section 105 of US Copyright Law, US government works are also not protected by copyright law. Unless they fall under copyright exceptions, US government works are meant to be dedicated to the public domain because the works are considered public resources.

Distinguishing Copyright from Other Types of Intellectual Property

Intellectual property is the term used for rights—established by law—that empower creators to restrict others from using their creative works. Copyright is one type of intellectual property, but there are many others. To help understand copyright, it is important to have a basic understanding of at least two other types of intellectual property rights and the laws that protect those rights.

- Trademark law generally protects the public from being confused about the source of a good, service, or establishment. The holder of a trademark is generally allowed to prevent use of its trademark by others if the public will be confused. Examples of trademarks are the golden arches used by McDonald’s, or the brand name Coca-Cola. Trademark law helps producers of goods and services protect their reputation, and it protects the public by giving them a simple way to differentiate between similar products and services.

- Patent law gives inventors a time-limited monopoly on their inventions—things like mouse traps or new mobile phone technology. Patents typically give inventors the exclusive right to make, have made, use, have used, offer for sale, sell, have sold, or import patentable inventions.

A few examples of other types of intellectual property rights include trade secrets, publicity rights, and moral rights.

For a brief introduction to the different types of intellectual property, watch the 3-minute video How to register a Trademark (Canada): Trademarks, Patents and Copyrights – What’s the Difference?