1. Talking about the human body

What will I be able to do at the end of this chapter?

- Distinguish between anatomy and physiology, and identify several branches of each

- Identify the different organ systems of the human body

- Use appropriate anatomical terminology to identify key body structures, body regions, and directions in the body

- Understand the logic behind basic medical terminology.

Though you may approach a course in anatomy and physiology strictly as a requirement for your field of study, the knowledge you gain in this course will serve you well in many aspects of your life. An understanding of anatomy and physiology is not only fundamental to any career in the health professions, but it can also benefit your own health.

Familiarity with the human body can help you make healthful choices and prompt you to take appropriate action when signs of illness arise. Your knowledge in this field will help you understand news about nutrition, medications, medical devices, and procedures and help you understand genetic or infectious diseases.

This chapter begins with an overview of anatomy and physiology and a preview of the body regions and functions. It then introduces a set of standard terms for body structures and positions in the body, as well as common medical terms that will serve as a foundation for more comprehensive information covered later in your degree courses.

1.1 | Overview of anatomy and physiology

Human anatomy is the scientific study of the body’s structures. In the past, anatomy has primarily been studied via observing injuries, and later by the dissection of anatomical structures of cadavers, but in the past century, computer-assisted imaging techniques have allowed clinicians to look inside the living body. Physiology explains how the structures of the body work together to maintain life. It is difficult to study structure (anatomy) without knowledge of function (physiology). The two disciplines are typically studied together because structure and function are closely related in all living things.

What is anatomy?

Human anatomy is the scientific study of the body’s structures. Some of these structures are very small and can only be observed and analysed with the assistance of a microscope. Other larger structures can readily be seen, manipulated, measured, and weighed. The word “anatomy” comes from a Greek root that means “to cut apart.” Human anatomy was first studied by observing the exterior of the body and observing the wounds of soldiers and other injuries. Later, physicians were allowed to dissect bodies of the dead to augment their knowledge. When a body is dissected, its structures are cut apart in order to observe their physical attributes and their relationships to one another. Dissection is still used in medical schools, anatomy courses and in pathology labs. In order to observe structures in living people, however, a number of imaging techniques have been developed. These techniques allow clinicians to visualise structures inside the living body such as a cancerous tumour or a fractured bone.

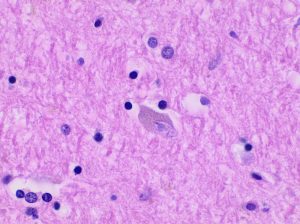

Like most scientific disciplines, anatomy has areas of specialisation. Gross anatomy is the study of the larger structures of the body, those visible without the aid of magnification (Figure 1.2a). Macro- means “large,” thus, gross anatomy is also referred to as macroscopic anatomy. In contrast, micro- means “small,” and microscopic anatomy is the study of structures that can be observed only with the use of a microscope or other magnification devices (Figure 1.2b). Microscopic anatomy includes cytology, the study of cells and histology, the study of tissues. As the technology of microscopes has advanced, anatomists have been able to observe smaller and smaller structures of the body, from slices of large structures like the heart to neuronal cells. Even the minute structures of an individual cell can be viewed by electron microscopes, as will be discussed in the next chapter.

Anatomists take two general approaches to the study of the body’s structures: regional and systemic. Regional anatomy is the study of the interrelationships of all of the structures in a specific body region, such as the abdomen. Studying regional anatomy helps us appreciate the interrelationships of body structures, such as how muscles, nerves, blood vessels, and other structures work together to serve a particular body region. In contrast, systemic anatomy is the study of the structures that make up a discrete body system—that is, a group of structures that work together to perform a unique body function. For example, a systemic anatomical study of the digestive system (an organ system) would consider all of the organs involved in digestion in the human body.

What is physiology?

Whereas anatomy is about structure, physiology is about function. Human physiology is the scientific study of the chemistry and physics of the structures of the body and the ways in which they work together to support the functions of life. Much of the study of physiology centres on the body’s tendency toward maintaining homeostasis. Homeostasis is the state of steady internal conditions maintained by living things. This steady state for conditions, such as temperature and concentration of diverse chemicals, is necessary for the body to function properly.

The study of physiology certainly includes observation, both with the naked eye and with microscopes, as well as manipulations and measurements. However, current advances in physiology usually depend on carefully designed laboratory experiments that reveal the functions of the many structures and chemical compounds that make up the human body.

Like anatomists, physiologists typically specialise in a particular branch of physiology. For example, neurophysiology is the study of the brain, spinal cord, and nerves and how these work together to perform functions as complex and diverse as vision, movement, and thinking. Physiologists may work from the organ level (exploring, for example, what different parts of the brain do) to the molecular level (such as exploring how an electrochemical signal travels along nerves).

Structure and function: Form (anatomy) follows function (physiology) is one of the Core Concepts or basic principles of anatomy and physiology. The form of any structure in the body is complementary to its function. This is true at all levels of organisation, from chemical compounds to organ systems. For example, the thin flap of your eyelid can snap down to clear away dust particles and almost instantaneously slide back up to allow you to see again. At the microscopic level, the arrangement and function of the nerves and muscles that serve the eyelid allow for its quick action and retreat. At an even smaller level of analysis, the function of these nerves and muscles likewise relies on the interactions of specific molecules and ions. Even the three-dimensional structure of certain molecules is essential to their function.

Your study of anatomy and physiology will make more sense if you continually relate the form of the structures you are studying to their function. In fact, it can be somewhat frustrating to attempt to study anatomy without an understanding of the physiology that a body structure supports. Imagine, for example, trying to appreciate the unique arrangement of the bones of the human hand if you had no conception of the function of the hand. Fortunately, your understanding of how the human hand manipulates tools—from pens to cell phones—helps you appreciate the unique alignment of the thumb in opposition to the four fingers, making your hand a structure that allows you to pinch and grasp objects and type text messages.

1.2 | Organ systems of the human body

It is convenient to view the body primarily as a collection of organ systems which work together to maintain its life and health.

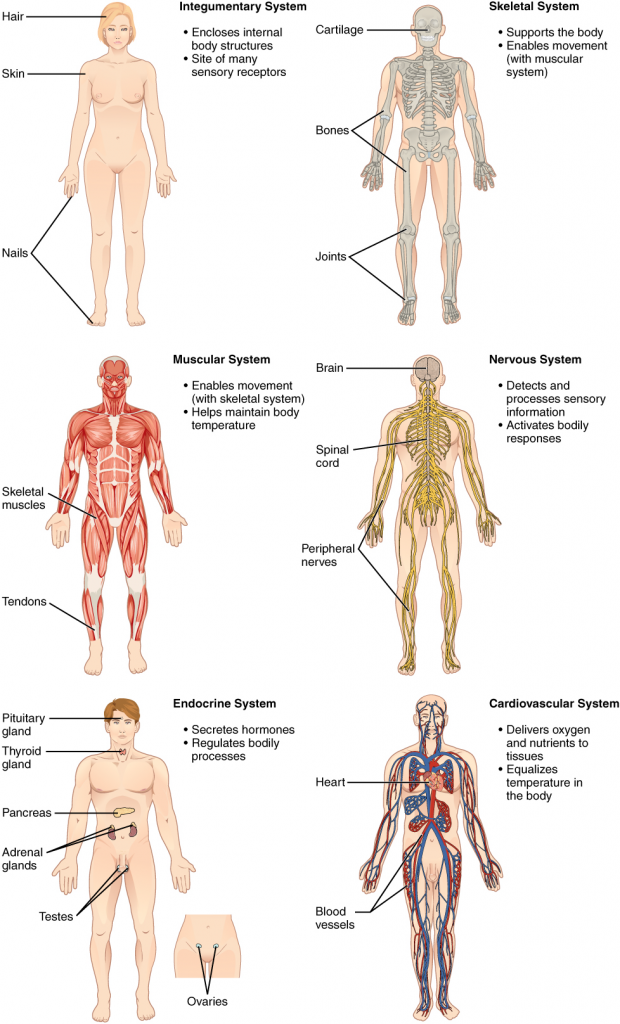

What are the 11 organ systems?

Figure 1.3 represents the 11 distinct body organ systems. Assigning organs to organ systems can be imprecise since organs that belong to one system can also have functions integral to another system. In fact, most organs contribute to more than one system.

1.3 | Anatomical terminology

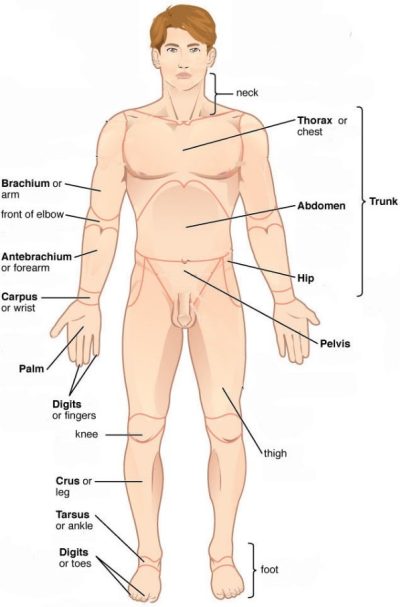

Anatomists and health care providers use terminology that can be bewildering to the uninitiated. However, the purpose of this language is not to confuse, but rather to increase precision and reduce medical errors. For example, is a scar above the wrist located on the forearm two or three inches away from the hand? Or is it at the base of the hand? Is it on the palm side or back-side? By using precise anatomical terminology, we eliminate ambiguity. Anatomical terms derive from ancient Greek and Latin words.

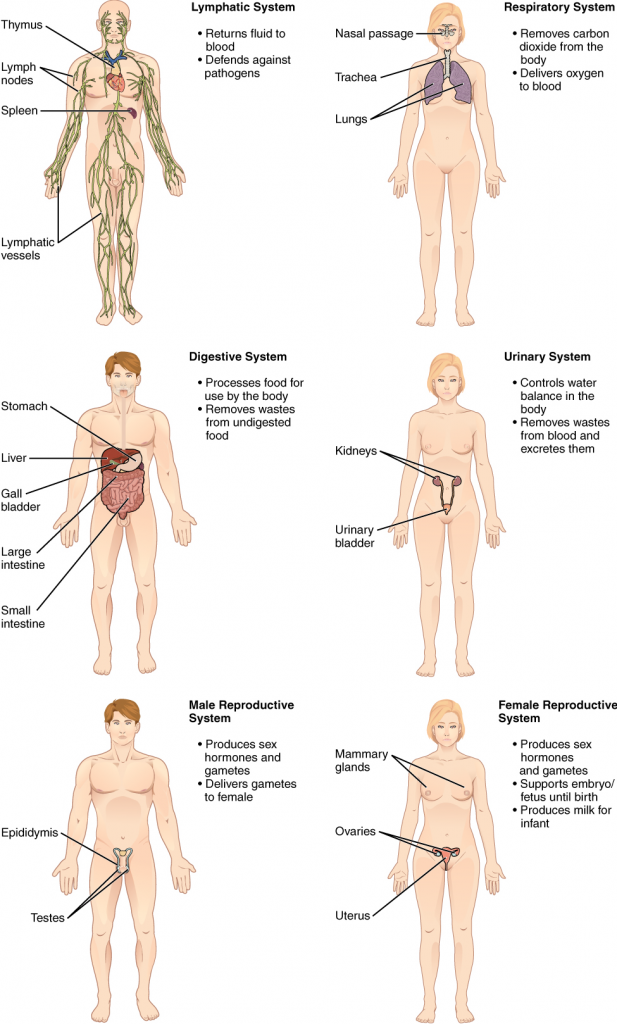

What is anatomical position?

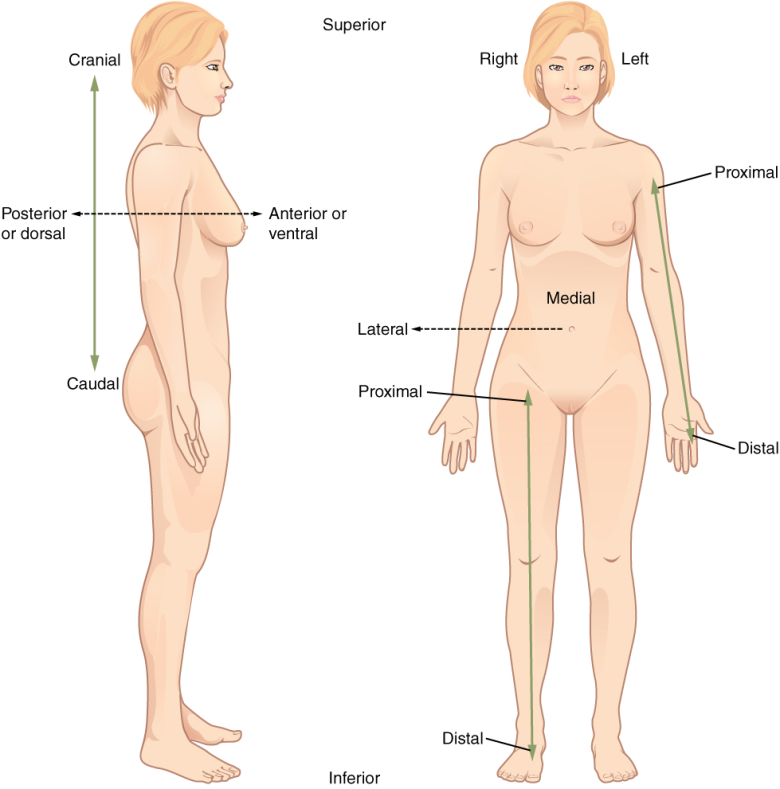

To further increase precision, anatomists standardise the way in which they view the body. Just as maps are normally oriented with north at the top, the standard body map, or anatomical position, is that of the body standing upright, with the feet at shoulder width and parallel, toes forward. The upper limbs are held out to each side, and the palms of the hands face forward as illustrated in Figure 1.4. Using this standard position reduces confusion and therefore,

- Anterior denotes towards the front

- Posterior denotes towards the back

Note that special terms are also used for the various regions of the body.

It does not matter how the body being described is oriented, the terms are used as if it is in anatomical position. For example, a scar in the anterior (front) carpal (wrist) region would be present on the palm side of the wrist. The term anterior would be used even if the hand were palm down on a table.

A body that is lying down is described as either prone or supine. Prone describes a face-down orientation, and supine describes a face up orientation. These terms are sometimes used in describing the position of the body during specific physical examinations or surgical procedures.

What are directional terms?

Certain directional anatomical terms appear throughout this and any other anatomy textbooks (Figure 1.5). These terms are essential for describing the relative locations of different body structures. For instance, an anatomist might describe one band of tissue as “inferior to” another or a physician might describe a tumour as “superficial to” a deeper body structure. Commit these terms to memory to avoid confusion when you are studying or describing the locations of particular body parts.

- Anterior (or ventral) describes the front or direction toward the front of the body. The toes are anterior to the foot.

- Posterior (or dorsal) describes the back or direction toward the back of the body. The popliteus is posterior to the patella (refer to Figure 1.4).

- Superior (or cranial) describes a position above or higher than another part of the body proper. The orbits of the eyes are superior to the oral cavity (mouth).

- Inferior (or caudal) describes a position below or lower than another part of the body proper; near or toward the tail (in humans, the coccyx, or lowest part of the spinal column). The pelvis is inferior to the abdomen.

- Lateral describes the side or direction toward the side of the body. The thumb (pollex) is lateral to the digits.

- Medial describes the middle or direction toward the middle of the body. The rib cage is medial to the arm (left or right).

- Proximal describes a position in a limb that is nearer to the point of attachment or the trunk of the body. The right elbow joint is proximal to the right hand.

- Distal describes a position in a limb that is farther from the point of attachment or the trunk of the body. The right hand is distal to the femur.

- Superficial describes a position closer to the surface of the body. The skin is superficial to the bones.

- Deep describes a position farther from the surface of the body. The brain is deep to the skull.

In addition, the following directional prefixes are also useful for understanding some of the content presented in this textbook:

- Epi: upper above

- Endo: inner, within

- Meso: middle, halfway, intermediate

- Trans: across

- Intra: within

- Inter: between

What are body planes?

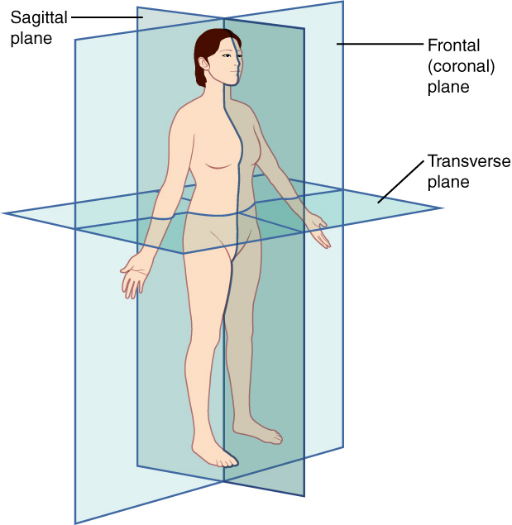

A section is a two-dimensional surface of a three-dimensional structure that has been cut. Modern medical imaging devices enable clinicians to obtain virtual sections of living bodies. We call these scans. Body sections and scans can be correctly interpreted, however, only if the viewer understands the plane along which the section was made. A plane is an imaginary two-dimensional surface that passes through the body. There are three planes commonly referred to in anatomy and medicine, as illustrated in Figure 1.6.

- The sagittal plane is the plane that divides the body or an organ vertically into right and left sides. If this vertical plane runs directly down the middle of the body, it is called the midsagittal or median plane. If it divides the body into unequal right and left sides, it is called a parasagittal plane or less commonly a longitudinal section.

- The frontal plane is the plane that divides the body or an organ into an anterior (front) portion and a posterior (rear) portion. The frontal plane is often referred to as a coronal plane. (“Corona” is Latin for “crown.”)

- The transverse plane is the plane that divides the body or organ horizontally into upper and lower portions. Transverse planes produce images referred to as cross sections.

How are the body cavities defined?

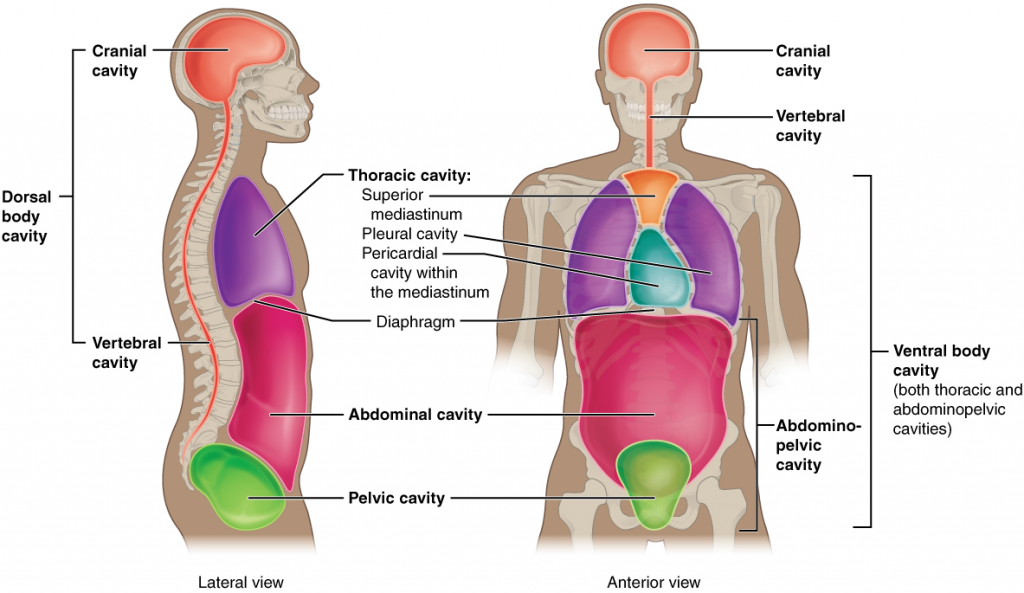

The body maintains its internal organisation by means of membranes, sheaths, and other structures that separate compartments. The dorsal (posterior) cavity and the ventral (anterior) cavity are the largest body compartments (Figure 1.7). These cavities contain and protect delicate internal organs, and the ventral cavity allows for significant changes in the size and shape of the organs as they perform their functions. The lungs, heart, stomach, and intestines, for example, can expand and contract without distorting other tissues or disrupting the activity of nearby organs.

Subdivisions of the posterior (dorsal) and anterior (ventral) cavities

The posterior (dorsal) and anterior (ventral) cavities are each subdivided into smaller cavities. In the posterior (dorsal) cavity, the cranial cavity houses the brain, and the spinal cavity (or vertebral cavity) encloses the spinal cord. Just as the brain and spinal cord make up a continuous, uninterrupted structure, the cranial and spinal cavities that house them are also continuous. The brain and spinal cord are protected by the bones of the skull and vertebral column and by cerebrospinal (cerebro = brain) fluid, a colourless fluid produced by the brain, which cushions the brain and spinal cord within the posterior (dorsal) cavity.

The anterior (ventral) cavity has two main subdivisions: the thoracic cavity and the abdominopelvic cavity (see Figure 1.7). The thoracic cavity is the more superior subdivision of the anterior cavity, and it is enclosed by the rib cage. The thoracic cavity contains the lungs and the heart, which is located in the mediastinum. The diaphragm forms the floor of the thoracic cavity and separates it from the more inferior abdominopelvic cavity. The abdominopelvic cavity is the largest cavity in the body. Although no membrane physically divides the abdominopelvic cavity, it can be useful to distinguish between the abdominal cavity, the division that houses the digestive organs, and the pelvic cavity, the division that houses the organs of reproduction.

How does medical terminology work?

In addition to the anatomical terms described above, it is useful to discuss the origin of other types of medical terms. Again, most medical terms usually have Latin or Greek origin. These terms are generally made up of 3 parts: roots, prefixes, and suffixes. The most common form of these words is, prefix-root-suffix. For example, epi-cardi-um. This term refers to the tissue on the surface of the heart.

Root words are the main subject of the compound term. They usually refer to the specific structure or organ (Table 1.1), for example, the Latin ren/o means kidney, therefore renal failure describes kidney failure; further, the heart is represented by the term Cardi/o, therefore cardiac arrest describes heart failure. Often there is a joining vowel between the root word and the suffix, in the two examples just given it is the letter o. The combination of the root word and the joining vowel is known as the combining form.

| Organ/ system | Root word | Example of medical term | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| lungs | pneum | pneumonia | infection of the lungs |

| skin | derm | dermatitis | inflammation of the skin |

| joint | arthr | arthritis | painful inflammation of joints |

| foot | pod | podiatry | care of the human foot |

| blood | haem | hemolysis | rupture of the blood cells |

| nose | rhin | rhinoplasty | plastic surgery on nose |

| stomach | gastr | gastritis | inflammation of the stomach lining |

| heart | cardi | cardiologist | person who specialises in diseases of the cardiovascular system |

| cell | cyt | leukocyte | white blood cell |

| muscle | myo | myocyte | muscle cell |

Note that most of the words in the table above do not have a prefix, the root word is at the beginning of the word, followed by a suffix. It is also possible to have two root words for example myo-cardi-um, muscle tissue of the heart.

The prefix describes the root word. It provides information about things like colour, amount, size, position/location or directions. Some common examples of each are shown in Table 1.2.

| Prefix | Meaning | Example |

| Amount | ||

| Mono- | One | Monosaccharide |

| Bi-/Di- | Two | Bipolar |

| Tri- | Three | Triglyceride |

| Poly- | Many | Polypeptide |

| Oligo- | A few | Oligosaccharide |

| A- | Without | Abiotic |

| Hyper- | Above | Hypertension |

| Hypo- | Below | Hypotonic |

| Colour | ||

| Alb- | Pale | Albino |

| Cyan- | Blue | Cyanosis |

| Erythr- | Red | Erythrocyte |

| Time | ||

| Ante- | Before | Ante-natal |

| Pro- | Before | Probiotic |

| Pre- | Before | Preoperative, Prefix |

| Post- | After | Postnatal |

| Neo- | New | Neonatal |

| Speed | ||

| Tachy- | Fast | Tachycardia |

| Brady- | Slow | Bradycardia |

| Location/Position | ||

| Epi- | Above, On | Epicardium |

| Endo- | Inside | Endocardium |

| Extra- | Outside | Extracellular |

| Sub- | Below | Subdural |

| Hypo- | Below | Hypodermic |

| Inter- | Between | Interstitial fluid |

| Intra- | Inside | Intracellular |

| Peri- | Near | Pericardial sac |

The suffix is the end part of the term. In medical terminology, it generally refers to a procedure, test, condition, disorder or disease. Some common examples are shown in Table 1.3.

| Suffix | Meaning | Example |

| -algia | Pain | Myalgia |

| -ectomy | Surgical removal | Appendectomy |

| -gram | Picture | Encephalogram |

| -ia | Condition | Paraplegia |

| -ic | Pertaining to | Acidic |

| -ism | Condition | Hyperthyroidism |

| -itis | Inflammation | Gastritis |

| -logy | The study of | Biology |

| -lysis | Break apart | Haemolysis |

| -megaly | Enlargement | Cardiomegaly |

| -meter | Instrument used to measure | Thermometer |

| -ole/-ule | Small | Arteriole/ venule |

| -osis | Condition | Osteoporosis |

| -rrhea | Discharge | Rhinorrhea |

| -um | Single thing | Duodenum/ Epicardium |

Crossword Puzzle

Key terms

abdominopelvic cavity division of the anterior (ventral) cavity that houses the abdominal and pelvic viscera (organs)

anatomical position standard reference position used for describing locations and directions on the human body

anatomy science that studies the form and composition of the body’s structures

anterior describes the front or direction toward the front of the body; also referred to as ventral

anterior cavity larger body cavity located anterior to the posterior (dorsal) body cavity; includes the serous membrane-lined pleural cavities for the lungs, pericardial cavity for the heart, and peritoneal cavity for the abdominal and pelvic organs; also referred to as ventral cavity

caudal describes a position below or lower than another part of the body proper; near or toward the tail (in humans, the coccyx, or lowest part of the spinal column); also referred to as inferior

cranial describes a position above or higher than another part of the body proper; also referred to as superior

cranial cavity division of the posterior (dorsal) cavity that houses the brain

deep describes a position farther from the surface of the body

distal describes a position farther from the point of attachment or the trunk of the body

dorsal describes the back or direction toward the back of the body; also referred to as posterior

dorsal cavity posterior body cavity that houses the brain and spinal cord; also referred to the posterior body cavity

frontal plane two-dimensional, vertical plane that divides the body or organ into anterior and posterior portions

histology the study of tissues

inferior describes a position below or lower than another part of the body proper; near or toward the tail (in humans, the coccyx, or lowest part of the spinal column); also referred to as caudal

lateral describes the side or direction toward the side of the body

medial describes the middle or direction toward the middle of the body

organ functionally distinct structure composed of two or more types of tissues

organ system group of organs that work together to carry out a particular function

physiology science that studies the chemistry, biochemistry, and physics of the body’s functions

plane imaginary two-dimensional surface that passes through the body

posterior describes the back or direction toward the back of the body; also referred to as dorsal

posterior cavity cavity that houses the brain and spinal cord; also referred to as dorsal cavity

prone face down

proximal describes a position nearer to the point of attachment or the trunk of the body

regional anatomy study of the structures that contribute to specific body regions

sagittal plane two-dimensional, vertical plane that divides the body or organ into right and left sides

spinal cavity division of the dorsal cavity that houses the spinal cord; also referred to as vertebral cavity

superficial describes a position nearer to the surface of the body

superior describes a position above or higher than another part of the body proper; also referred to as cranial

supine face up

thoracic cavity division of the anterior (ventral) cavity that houses the heart, lungs, oesophagus, and trachea

transverse plane two-dimensional, horizontal plane that divides the body or organ into superior and inferior portions

ventral describes the front or direction toward the front of the body; also referred to as anterior

Review Questions

Flashcards – alternatively use an app such as Quizlet to make your own cards

Chapter attribution

Content adapted from:

Anatomy and Physiology 2e (2022), by J. Gordon Betts, Kelly A. Young, James A. Wise, Eddie Johnson, Brandon Poe, Dean H. Kruse, Oksana Korol, Jody E. Johnson, Mark Womble and Peter DeSaix, is published by OpenStax https://openstax.org/details/books/anatomy-and-physiology-2e, and used under a CC BY licence.

Concepts of Biology (2013), by Samantha Fowler, Rebecca Roush and James Wise, is published by OpenStax https://openstax.org/details/books/concepts-biology, and used under a CC BY licence.

Microbiology (2016), by Nina Parker, Mark Schneegurt, Anh-Hue Thi Tu, Philip Lister and Brian M. Forster, is published by OpenStax https://openstax.org/details/books/microbiology, and used under a CC BY licence.

Media Attributions

- Figure 1.1 Blood pressure © Fort George G Meade Public Affairs Office is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- 800px-Brain_autopsy_lateral_view © Jensflorian is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Histology_of_thalamic_neuron © Mikael Häggström, M.D. is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Figure 1.3a Organ Systems © Openstax is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Figure 1.3b Body Systems © Openstax is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Figure 1.4 The standard anatomical position © Openstax is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Figure 1.5 Directional terms. © Openstax is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Figure 1.6 Planes of the Body © OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Figure 1.7: Dorsal and ventral body cavities © OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license