7 Solution-Focussed Brief Therapy and Regional Students

Mitch Griffiths

Adolescence is a critical stage of human development which is recognised as a peak time of formulative influence and cognitive development. The fragile nature of this phase can leave the individual open to external influences, none more damaging than the impacts of trauma, which can have devastating, lifelong consequences if left untreated. Recent Australian research indicates a concerning outlook toward the mental health of adolescents living in regional Australia with the impact of trauma playing a significant role in adolescent wellbeing. Through the research process of this literature review, backed by my professional experience in a regional context, I posit a shift to brief, strength-based interventions, in particular the application of a Solution-Focused Brief Therapy (SFBT) within career counselling, as an intervention model to assist the facilitation of hope and subjective well-being among regional trauma impacted adolescents seeking transition into employment. It is hoped the application of SFBT in this regional environment may inform psychological practice in the context of adolescent trauma while assisting the successful transition into employment within regional Australia.

Introduction

There is increasing interest in brief, strength-based approaches to facilitate adolescent trauma interventions with SFBT emerging as a potentially significant perspective in this treatment field.

While Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) has long been held as a treatment of choice for many mental health issues, and is supported by the guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (Beck, 1976; Beck, Freeman, & Davis, 2007), there is growing research indicating support for the application of SFBT as an intervention model given its strength-based, solution-oriented approach, allowing clients to focus on hope and subjective wellbeing. (Joubert & Guse, 2021 p. 149).

Research into Australian adolescent mental health will be highlighted within this literature review with a primary focus on SFBT’s application as a therapeutical approach within career counselling to assist adolescents impacted by trauma transition toward long term employment in regional Australia.

The hypothesis toward the need for a supportive strength-based approach to assist the facilitation of self-efficacy into employment is reaching paramount proportions with research by Ivancic et al. (2014) finding 14% of adolescents aged 12-17 years experienced mental health concerns in the past 12 months, with 23% of associated respondents indicating a severe level of disorder, while one in thirteen 12–17-year-olds had seriously considered attempting suicide in this time frame.

Supporting these concerning statistics, is the association of earlier findings by Parker and Tovim (2002) which indicated suicide rates among Indigenous Australians are four times higher than their non-Indigenous counterparts. In some remote communities in the Kimberley, rates of suicide have reached one hundred times the national suicide average.

These astounding statistics have many contributing factors with socioeconomic status overshadowing many other areas of concern with a greater prevalence in Australia’s regional and remote communities. To give perspective of regional population decline, statistics taken from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) indicate the turn of the century saw 50% of Australia’s population living on rural properties or towns of fewer than 3000 people. By mid-century, dramatic decline was evident with three in five Australians living in a city with a population greater than 100,000, and by the turn of the century, two in three Australians lived in a capital city. This evident decline could provide insight into possible influence on growing mental health concerns for regional Australian adolescents. (ABS 2022).

The ramification of this disparity between regional Australia and its major urban counterparts is but one facet of the growing mental health crisis facing our adolescent population. The purpose of this study is to investigate and highlight areas of concern for adolescent populations in regional Australia while positing a strength-based approach to therapy and its potential benefits to this cohort.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

| Australian peer reviewed journal articles | Non peer reviewed works |

| Works published within the last 20 years | International research statistics |

| JCU subject readings | |

| Works cited frequently by research in the same discipline |

Regional Australia’s Adolescent Well-Being

The developmental stage of adolescents is a complex area of human development, combined with the implications of trauma, the context of regional living, and the transition phase from schooling to employment there is an opening to a complex field of study.

These complexities will be investigated with the ramifications of these concurrent impacts on this cohort clearly outlined through current research findings.

Currently, SFBT holds a stigma in the field of counselling due to its relatively short duration of treatment and limited longitudinal empirical evidence. I posit SFBT’s application within career counselling for trauma-based adolescents as a positive application to assist the development of client self-efficacy in a cohort where client stability in accessing consistent treatment opportunities can be challenging due to the transient nature of this age bracket.

What is Australia’s Current Adolescent Wellbeing Situation?

Adolescence and young adulthood as a peak time of formative influence with the detrimental impacts of trauma well noted in research, estimates of trauma-exposure rates vary depending on the types of traumas encountered by the client, with research by Breslau (2004, p. 535) indicating “up to 82% of young people report exposure to one or more interpersonal traumas by the time they reach age 23.”

Associated findings are indicated in research by Kieling et al. (2011) noting concerning statistics globally relating to adolescent mental health, finding that 10-20% of adolescents worldwide are affected by mental health problems. These global findings are equally mirrored in Australian research findings, with current indications showing a rise in concern for Australia’s adolescent mental health status with trauma often elevating these concerns.

The 2007 ABS National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing indicates one-quarter of Australians aged 16 to 24 had experienced mental health concerns, with one-third of respondents indicating moderate to high psychological distress over the 12-month period.

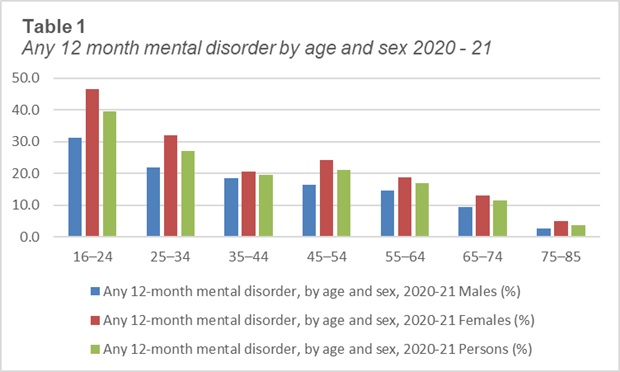

These statistics are unfortunately overshadowed by the most recent 2021 survey findings of the ABS, stating almost two in five people (39.6%) aged 16-24 years had a mental disorder within the previous 12-month period as indicated in Figure one.

The prevalence of mental health disorders in Australian adolescents is not only evident but disturbing when compared with the featured age groups in Table one. Further research into the correlation between associated trauma and these mental health findings could give an interesting body of evidence to support the application of SFBT in a regional career counselling context. While these recent ABS findings are concerning, given the timing of this survey, one needs to consider the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on this cohort study to gain a true gauge on the presenting statistics.

Supporting the findings of the National Mental Health and Wellbeing survey are the longitudinal survey results of Mission Australia, which indicate similar adolescent mental health statistics as outlined in subsequent Youth Surveys spanning the past 20 years.

The initial survey undertaken in 2001–2002 among a sample of adolescents aged 15 – 19 years indicated the prevalence of probable serious mental illness for over 20% of respondents, further findings in the second survey indicated 13% of respondents rated in the very high psychological distress category, with the third survey conducted in 2021 indicating over 15% rating their mental health and wellbeing as poor Tiller et al., (2021).

Further evidence supporting the findings of Mission Australia’s youth surveys is the AG’s Mental Health of Children and Adolescents report (2015) which focused on adolescents aged four – 17. This report tables the findings of The Young Minds Matter Survey, which indicates a prevalence of very high psychological distress rates of over 13% within this adolescent population.

These statistics equate to almost 1:7 four – 17-year-olds or 560,000 Australian children and adolescents being assessed as having mental disorders in the previous 12 months (Lawrence et al., 2015). Concerningly, the above-mentioned findings are supported by The Black Dog Institute’s 2016 Youth Mental Health report which indicates suicide as the leading cause of death among young people aged 15-24 years (2012 – 2016).

While the validity of survey-based research methods requires further investigation to ensure equitable application, questioning, and cohort selections were applied, these pre-pandemic statistics should raise great concern for those of us operating in this field of regional career counsel.

A note of strength for clients relating to regional living is noted in the research by Byun et al. (2012 p. 89) who indicates rurality can come with distinct advantages with findings indicating that “rural youth tend to have high levels of family and community capital, and these strong attachments are positively related to academic achievement and college completion.” With smaller schools generally based in regional areas generating higher levels of social capital due to the cultivation of “feelings of belonging and commitment to education beyond high school” (Nelson, 2019 p. 89).

How do Adolescents Respond to Trauma?

Traumatic events have become pervasive, globally more than two-thirds of the population will experience a traumatic event at some point in their lives (Benjet et al., 2016; Froerer et al., 2018). Supporting these findings at a local level is the research of Nooner et al. (2012) whose research findings estimate 80% of Australian adolescents have experienced at least one traumatic event and one in seven suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Trauma is a complex area requiring careful consideration in the therapeutic space, adverse experiences, such as sexual abuse, disengagement from school, neglect, family breakdown, and psychosocial failings, are known risk factors for the development of mental health issues and have been linked to the occurrence of mood disorders, substance misuse, posttraumatic stress disorder, and personality disorders (Cutuli et al. 2013; Dackis et al. 2012; Larson et al. 2017).

To understand these implications deeply, insight is required into the critical periods of neurological development which could consequently assist supporting agency’s efforts to target these behavioural concerns at critical points in neurological development.

It is now common knowledge that during adolescence, the brain is highly plastic which is an essential component for normal development. Consequently, this plasticity also allows the developing brain to be highly susceptible to the harmful effects of trauma, which in turn has the potential to disrupt development. The brain is highly plastic which is an essential component for normal development. Consequently, this plasticity also allows the developing brain to be highly susceptible to the harmful effects of trauma, which in turn has the potential to disrupt development. The detrimental impact of adversity and stress directly correlates to the vulnerability of the hippocampus, a complex brain structure embedded deep in the temporal lobe. The hippocampus has a major role in learning and memory, forming part of the limbic system, which is particularly important in regulating emotional responses (Uematsu et al., 2012).

Recent cross-sectional research into adolescent neglect and abuse revealed a physiological anomaly hypothesising a structural change in the adolescent brain, specifically the hippocampus, when exposed to stressful situations as experienced in traumatic events.

Findings noted stress impacts the structure of the hippocampus with evidence suggesting chronic levels of stress can induce a reduction in dendritic complexity particularly in the CA3 subfield.

Interestingly a study by Teicher et al. (2018) revealed that the CA3 subfield “was most susceptible to stress-induced changes, and abuse exposure at the ages of six, 10 to 12 and 16 years”. These findings suggest developmentally critical periods providing “temporal windows of vulnerability” in the development during adolescence.

Given the impact trauma is thought to have on the adolescent brain, in particular the hippocampal region, the implication of this relationship is substantial. Counsellors must consider the possibility that the very area of the brain they are aiming to connect with in the adolescent field, that of regulation and emotional response, may be damaged or malformed due to the impacts of trauma.

How do we best apply treatment modalities to assist adolescents who may have an inability to regulate their emotional responses? Is a deficit model going to elicit a strong unregulated emotional response or should we be seeking to focus on a strength-based approach when dealing with adolescent mental health?

Is Solution Focus Brief Therapy (SFBT) an Appropriate Treatment Option for Adolescents Impacted by Trauma?

Developed in the 1980s by Steve De Shazer and Insoo Kim Berg, SFBT rests on the foundation that clients are the experts in their own lives and therefore, hold a solid understanding of what approaches have, or have not worked in the past, and what choices may work for them in the future.

Its focus emphasises client strengths, and how client insight into these strengths can be applied to the change process. Rather than focusing on the problem, SFBT orients clients to a future without the problem.

Counsellors working with traumatised adolescents in regional career-based counselling generally face a limited scope of time to engage with clients due to the transient living arrangements, such factors imply the need for engagement in therapy modalities that offer a short duration of treatment in which SFBT is well aligned to accommodate.

While it can be argued trauma requires deeper investigation into the root cause of the presenting issues, there are many studies outlining the possible detriment of revisiting trauma with a growing interest in a strength-based therapeutic approach.

Earlier research by Pitman et al., (1991) and Tarrier et al., (1999a) into trauma modality approaches indicate increased dropout rates due to difficulties faced when trauma-impacted clients are exposed to trauma-focused psychological therapies. It is theorised these approaches can present difficulty for clients when confronting traumatic images or revisiting past traumatic events.

There is evident research, including the findings of Cahill et al. (2006), Paintain & Cassidy (2018) and Tong et al. (2019), supporting the theory of exposure-orientated approaches inducing exceptionally high dropout rates due to client’s unwillingness to relive traumatic events due to the associated increase of anxiety and distress. It is likely that posttraumatic avoidance was the source of an unwillingness to think about, accept the existence of, or feel emotions associated, with the trauma experience.

Giving agency to the client through the application of SFBT questioning techniques allows the client to determine what is important in that moment to discuss, gives credit and space to negative or difficult emotions, and collaborates with the clients small steps toward healing.

The spectrum of adverse psychological responses trauma clients can exhibit, gives rise to a focus on client strength when dealing with time-restricted, trauma-based adolescents. Such an approach could assist the development of client agency rather than focusing on historical problems, I would argue that SFBT may be particularly relevant in this context.

In congruence with the application of a strength base approach for trauma-based clients, Cloitre’s (2015 p. 2) research outlines “most exposure-oriented approaches are described as rigid and time-consuming; hence, clients and clinicians are seeking approaches that are flexible, brief, and effective”, all of which are key components of the adolescent world.

Joubert and Guse (2021) also note these traditional exposure-oriented approaches are often criticized for disregarding the need to focus on the client’s natural resiliency, with Lloyd and Dallos stating, “visualising one’s desired outcome/preferred future in detail also leads to conversations characterised by possibility, change, hope, and self-efficacy” (2008, p. 10).

This association indicates a congruence in the application of SFBT as trauma intervention facilitating hope and subjective wellbeing, given that adolescence is such a formulative developmental window, the application of positive psychological interventions to promote positive emotions, and behaviours to increase the wellbeing of an individual should be at the forefront of adolescent psychotherapy.

Given the growing support of a strength-based approach, Gilman et al. (2012) highlight the need to explore how positive psychology interventions could instil hope and wellbeing in the context of trauma. Minimal empirical studies focusing on the use of SFBT with trauma survivors have been encountered during this literature review, therefore one would posit, at such a critical time in the development of an individual’s self-efficacy within the stages of adolescents, the application of a strength-based, solution-focused approach such as SFBT, despite the impacts of trauma, should be at the forefront of treatment options to enhance subjective well-being and positive self-efficacy during this complex developmental period.

The Impact of the Problem

Based on the research taken to date a significant gap exists in the research, particularly relating to the area of trauma and regional Australian adolescent employment statistics. What is clear in the research to date, is the overwhelming impact trauma has on adolescent development.

As this research project has developed, so too has the initial research question which has evolved to focus more on the impacts of trauma on the critical phase of human development in adolescents, and less on transition to employment given the lack of empirical evidence relating to regional trauma impacted adolescents transitioning to employment.

There is an undeniable and significant burden on the Australian health system, with research into the impact of trauma on the human brain indicating a growing need for early intervention strategies to assist adolescents navigate this formative period of development.

Exposure to trauma produces a wide spectrum of adverse psychological responses, from mild disequilibrium to severe and chronic ongoing distress conditions such as PTSD, anxiety, and depression. Traditional therapeutic approaches such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) have often been criticized for disregarding the client’s existing strengths, with research toward the application of exposure-orientated approaches also indicating high dropout rates attributed to the requirement of the client to ‘re-visit’ traumatic events increasing anxiety and distress.

Given the formative developmental window of adolescents, research indicates this period of development is strongly linked to a distinct susceptibility toward the impact of trauma and substance misuse (Brady & Back, 2012; Gerson & Rappaport, 2013; Hall et al., 2016). Supporting this research is the findings of Purcell et al. (2011) indicating the highest burden of mental health disorders in Australia lies with adolescents between the ages of 15– 24 years. These findings support a clear indication this association between trauma and adolescents requires substantiative focus on treatment approaches toward adolescent mental health in Australia.

A ramification of this concurrence between the formative nature of adolescents and exposure to trauma indicates trauma experienced in this phase can lead to lifelong mental health-related issues.

Firsthand experience gained in alternative education facilities catering to adolescents in regional Queensland has given a deep insight into such issues, I can strongly support the findings of Altintas & Bilici 2018; Fox et al. (2015) who note traumatised young people in particular, are more likely to come to the attention of police and juvenile justice systems than their non-traumatized peers, with Kessler et al. (2013) noting “the wider impact of adolescent trauma as an issue of significant public health concern.

My experience has involved me in the significance of adolescent trauma and the resulting impact on the wider community ranging from substance misuse to property offences, and violence which generally is inherent within the extended family and community.

The impact of trauma is significant in the eyes of the community with some adolescent behavioural choices leading to crime and incarceration alongside the ramification of ongoing mental health concerns. Recent studies indicate high rates of adolescents impacted by trauma and a growing concern toward the far-reaching impact trauma is playing in the lives of regional Australia’s adolescent populations and associated health systems.

The aim of a short term, strength-based therapeutic approach, could offer an appropriate, targeted intervention for clinicians working with transient regional adolescents by assisting in the development of self-efficacy and independence in the transitional phase from education to employment.

Potential Benefits to Clients, Community, and the Counselling Profession if the Problem is Resolved

If young people were able to operate from a strength-based approach and recognise their existing supports, are we not giving them the best opportunity for independence in the community? If we can elicit a problem-free future vision, based on current strengths the client has displayed by overcoming traumatic experiences, are we not developing self-efficacy for the young person?

Certain aspects of SFBT make its application for trauma-impacted adolescents an ideal approach within career counselling. I posit the application of SFBT in a regional setting such as North Queensland to be well suited, due mainly to its short duration of application and a focus on existing client supports and strengths.

Adolescents can often resist discussion by remaining uncooperative or uncommunicative unless there is a solid relational connection with caring adults. In my professional experience working with transitional trauma-impacted adolescents, a positive strength-based, client-focused approach, is paramount to building a trusting relationship, which in turn, can foster a collegial, open approach between counsellor and client.

Given the client-directed focus of SFBT, an approach outlining the resilience and strength the client has already displayed to survive challenging and stressful life events should greatly assist the relational development toward self-efficacy.

There are countless examples daily of situations in which the client is doing what he or she is supposed to do or is wanting to do – a preferred future. The construction of solutions from these exceptions is surely more successful than focusing on or attempting to change an existing problem.

Therefore, self-efficacy is vital in the development of the resilience, and independence required in the post-school world. The ability to maintain employment within regional communities can be a difficult struggle given the lack of parental support many adolescents face. I therefore posit SFBT within career counselling sessions as an imperative step in building self-efficacy toward client independence in regional Australia.

The impacts of such application could have resounding results for regional communities enabling retention of regional youth through employment opportunities while assisting economic security within regional areas of Australia. More importantly, the focus of this application would be the development of self-efficacy for the mental health of the adolescent population in regional Australia.

Future Research

Based on the research taken to date, a significant gap in evidence exists in relation to the long-term effectiveness of SFBT’s application when working with trauma-impacted adolescents. These findings are concurrent with the research of Forerer et al. (2018 p. 3) who also note “only a small number of empirical studies have specifically focused on the use of SFBT with trauma survivors”.

Yet despite the high-risk nature of regional Australia’s adolescent populations mental health status, there is little empirical evidence indicating the efficacy of a strength-based approach as a favourable treatment outcome for adolescent clients.

Adding to this concern are further findings of this research project which note the critical to non-existent gap in research relating to the field of trauma-impacted regional adolescents gaining and maintaining a successful transition into employment.

These highlighted gaps show a critical need for longitudinal studies to assess the impact of SFBT as a treatment approach for adolescent trauma during the transitional phase into employment in regional Australia.

I posit the application of SFBT as a modality to support career counselling sessions in my current professional context. Working with trauma-impacted adolescents in regional Queensland is a field requiring further research to assess the long-term effectiveness of SFBT’s ability to support regional adolescents and their transition to employment.

Conclusion

The proposal of a strength-based approach could play a significant role in the treatment of trauma-impacted adolescents due to the facilitation of hope, subjective wellbeing, and the highlighting of client strengths and resources within an SFBT approach.

The benefits of SFBT’s application to highlight client strengths and resources is well researched however there are notable gaps in research on SFBT’s application and long-term effectiveness when working with trauma-impacted adolescents.

Longitudinal studies investigating the effectiveness of SFBT’s application in this field are warranted to assess the validity of this approach with a particular focus on dropout rates which are notably prevalent in other therapeutic approaches with trauma-based clients.

The main rationale supporting the application of SFBT techniques with trauma-impacted adolescents lies in its brevity of application. An initial SFBT conversation can assist a movement towards a better tomorrow, therefore, one of the main hurdles facing trauma-impacted regional adolescents could be best addressed through the integration of a brief, strength-based, resource highlighting, future-oriented approach.

References

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2020-2021). National Study of Mental Health and Wellbeing. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/mental-health/national-study-mental-health-and-wellbeing/2020-21

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2022, August). Labour Force, Australia. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/labour/employment-and-unemployment/labour-force-australia/latest-release.

Australian Government Department of Education and Training. (2015). Longitudinal Surveys of Australian Youth, 2009 cohort: Study documentation.

Bennett, D., MacKinnon, P., & Richardson, S. (2016). Enacting strategies for graduate employability: How universities can best support students to develop generic skills: Final report 2016 (Part a). University of Melbourne, Curtin University, University of Sydney, Australian Council for Educational Research.

Black Dog Institute. (2012 – 2016). Youth mental health report. Youth Survey (2012-16). http://www.blackdoginstitute.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/2017-youth-mental-health-report_mission-australia-and-black-dog-institute.pdf?sfvrsn=6

Bostwick, K. C. P., Martin, A. J., Collie, R. J., Burns, E. C., Hare, N., Cox, S., Flesken, A., & McCarthy, I. (2022). Academic buoyancy in high school: A cross-lagged multilevel modeling approach exploring reciprocal effects with perceived school support, motivation, and engagement. Journal of Educational Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000753

Breslau, J. (2004). Introduction: Cultures of trauma: Anthropological views of posttraumatic stress disorder in international health. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, 28(2), 113–126. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:MEDI.0000034421.07612.c8

Chesters, J., & Cuervo, H. (2022). (In)equality of opportunity: Educational attainments of young people from rural, regional and urban Australia. The Australian Educational Researcher, 49(1), 43–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-021-00432-0

Douglas, L. J., Jackson, D., Woods, C., & Usher, K. (2019). Rewriting stories of trauma through peer‐to‐peer mentoring for and by at‐risk young people. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 28(3), 744–756. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12579

Dray, J., Bowman, J., Freund, M., Campbell, E., Hodder, R. K., Lecathelinais, C., & Wiggers, J. (2016). Mental health problems in a regional population of Australian adolescents: Association with socio-demographic characteristics. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 10(1), 32. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-016-0120-9

Finlayson, B. T., Hall, G. N., & Jordan, S. S. (2020). Integrating solution‐focused brief therapy for systemic posttraumatic stress prevention in paediatrics. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy, 41(2), 133–144. https://doi.org/10.1002/anzf.1410

Fiske, H. (2012). Hope in action: SolutionfFocused conversations about suicide. Taylor and Francis.

Franklin, C. (2012). Solution-focused brief therapy: A handbook of evidence-based practice. Oxford University Press. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&scope=site&db=nlebk&db=nlabk&AN=1213526

Froerer, A., Cziffra-Bergs, J. von, Kim, J. S., & Connie, E. (Eds.). (2018). Solution focused brief therapy with clients managing trauma. Oxford University Press.

Gilman, R., Schumm, J. A., & Chard, K. M. (2012). Hope as a change mechanism in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 4(3), 270–277. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024252

Ivancic, L., Perrens, B., Fildes, J., Perry, Y. and Christensen, H. (2014). Youth mental health report, June 2014. Mission Australia and Black Dog Institute.

Joubert, J., & Guse, T. (2021). A solution-focused brief therapy (SFBT) intervention model to facilitate hope and subjective well-being among trauma survivors. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 51(4), 303–310. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10879-021-09511-w

Kieling, C., Baker-Henningham, H., Belfer, M., Conti, G., Ertem, I., Omigbodun, O., Rohde, L. A., Srinath, S., Ulkuer, N., & Rahman, A. (2011). Child and adolescent mental health worldwide: Evidence for action. The Lancet, 378(9801), 1515–1525. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60827-1

Kivunja. (2016). How to write an effective research proposal for higher degree research in higher education: Lessons from practice. International Journal of Higher Education, 5(2), 163–172. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v5n2p163

Lawrence, D., Johnson, S. E., Hafekost, J., Boterhoven de Haan, K., Sawyer, M. G., Ainley, J., & Zubrick, S. (2015). The mental health of children and adolescents: Report on the second Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Department of Health.

Lehmann, P., Jordan, C., Bolton, K. W., Huynh, L., & Chigbu, K. (2012). Solution-focused brief therapy and criminal offending: A family conference tool for work in restorative justice. Journal of Systemic Therapies, 31(4), 49–62. https://doi.org/10.1521/jsyt.2012.31.4.49

Lewis, C., Roberts, N. P., Gibson, S., & Bisson, J. I. (2020). Dropout from psychological therapies for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 11(1), 1709709. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2019.1709709

Milnes, A. (2011). Young Australians: Their health and wellbeing 2011. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

Nelson, T. S. (2012). Handbook of solution-focused brief therapy clinical applications. Taylor and Francis.

Niccolai, A. R., Damaske, S., & Park, J. (2022). We won’t be able to find jobs here: How growing up in rural America shapes decisions about work. RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, 8(4), 87–104. https://doi.org/10.7758/RSF.2022.8.4.04

OECD. (2022). OECD employment outlook 2022: Building back more inclusive labour markets. https://doi.org/10.1787/1bb305a6-en

Parker, R., & Ben-Tovim, D. I. (2002). A study of factors affecting suicide in Aboriginal and ‘other’ populations in the Top End of the Northern Territory through an audit of coronial records. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 36(3), 404–410. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1614.2001.01032.x

Peters, I., Handley, T., Oakley, K., Lutkin, S., & Perkins, D. (2019). Social determinants of psychological wellness for children and adolescents in rural NSW. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 1616. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7961-0

Peters, W., Rice, S., Cohen, J., Murray, L., Schley, C., Alvarez-Jimenez, M., & Bendall, S. (2021). Trauma-focused cognitive–behavioral therapy (TF-CBT) for interpersonal trauma in transitional-aged youth. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 13.

Phillips, A. (2008). Rural, regional, and remote health: Indicators of health status and determinants of health. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (3), 313–321. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0001016

Poole, M. E. (1985). School and work: Expectations of adolescents in transition. Education Research and Perspectives, 12(2), 10–18. https://search-informit-org.elibrary.jcu.edu.au/doi/10.3316/ielapa.860503529

Rahmat, S., & O’Connor, R. (2022). Transitional-age youth with chronic medical and mental health conditions. Psychiatric Annals, 52(6), 227-231. https://doi.org/10.3928/00485713-20220525-01

Rowell, L. L. (2006). Action research and school counseling: Closing the gap between research and practice. Professional School Counseling, 9(5), 376-384.

Seet, P-S., & Jones, J. (2020, February 17) If you’re preparing students for 21st century jobs, you’re behind the times. https://theconversation.com/if-youre-preparing-students-for-21st-century-jobs-youre-behind-the-times-131567

Schollar-Root, O., Cassar, J., Peach, N., Cobham, V. E., Milne, B., Barrett, E., Back, S. E., Bendall, S., Perrin, S., Brady, K., Ross, J., Teesson, M., Kihas, I., Dobinson, K. A., & Mills, K. L. (2022). Integrated trauma-focused psychotherapy for traumatic stress and substance use: Two adolescent case studies. Clinical Case Studies, 21(3), 192–208. https://doi.org/10.1177/15346501211046054

Milton H. Erickson Foundation. (2020, Jan 01). The solution oriented approach to change: Brief therapy method to finding the answers within clients, in Evolution of Psychotherapy, Workshop 5 [Video]. https://proquest.com

Tiller, E., Greenland, N., Christie, R., Kos, A., Brennan, N., & Di Nicola, K. (2021). Youth survey report 2021. Mission Australia.

Tong, J., Simpson, K., Alvarez‐Jimenez, M., & Bendall, S. (2019). Talking about trauma in therapy: Perspectives from young people with post‐traumatic stress symptoms and first episode psychosis. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 13(5), 1236–1244. https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.12761

Bright, G., & Harrison, G. (2013). Understanding research in counselling. SAGE Publications.

Van Rijn, B. (2014). Assessment and case formulation in counselling and psychotherapy. SAGE Books. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781473910867

Walsh, L., & De Campo, J. (2010). Falling through the cracks. Professional Educator, 9(1), 30–32.

White, M. A., & Waters, L. E. (2015). A case study of ‘The Good School:’ Examples of the use of Peterson’s strengths-based approach with students. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 10(1), 69–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2014.920408

Zimmer-Gembeck, M., & Mortimer, J. T. (2006). Adolescent work, vocational development, and education. Review of Educational Research, 76(4), 537-566.