1 Can Filial Therapy in Early Education Settings Improve Student Well-Being and Educational Engagement for Children in Long-Term Out-of-Home Care?

Kristy Koci

Abstract

Filial Therapy (FT) is a therapeutic intervention aimed at strengthening the relationship between the child and caregiver through the use of non-directive play. The focus of FT on developing secure attachment between the child and caregiver, makes it particularly suitable for children and young people in out-of-home care (OOHC) and there is a raft of research supporting its effective application in this context. This literature review has been prepared to inform the design of a research project which seeks to investigate the effectiveness of FT, applied in an early education setting, to improve the well-being and educational engagement of children in long-term OOHC in North Queensland, Australia. It sets out an analysis of the cause and impact of the educational disadvantage faced by children in OOHC, provides a summary of relevant research, and identifies key gaps which must be addressed by future research to develop effective school-based Filial Therapy (SBFT) programmes tailored toward children in OOHC in North Queensland and further afield.

Keywords: Filial Therapy, non-directive play therapy, out-of-home care, educational engagement, student wellbeing

Introduction

Children in out-of-home care (OOHC) face significant disadvantage in many aspects of life, not least in the areas of education and well-being. Research shows that compared to their peers, children in OOHC have lower levels of educational engagement and wellbeing which adversely impact their achievement throughout schooling and contribute to poorer overall life outcomes (NSW Department of Communities and Justice, 2020a). There is therefore a need for fit-for-purpose intervention strategies targeted toward improving educational engagement and well-being for children in OOHC.

FT is an effective strategy to strengthen the connections between the child and carer family, facilitate stronger commitment and academic support from carer families, enhance the child’s self-concept and may thereby facilitate better educational engagement and outcomes for children in OOHC. It is hypothesised the FT technique could be adapted for application in a school setting specifically targeted toward children in OOHC.

To investigate this hypothesis, a PhD research project is proposed seeking to address the question ‘Can Filial Therapy in early education settings improve student well-being and educational engagement for children in long-term out-of-home care?’. The research is anticipated to form the foundations of a school-based Filial Therapy (SBFT) programme, to be implemented by primary school Guidance Officers (GO) in North Queensland.

This literature review is intended to inform the design of the research project. It provides an analysis of the problem along with a summary of relevant research and key gaps to be addressed.

The Problem

Overview

Children in OOHC represent one of the most disadvantaged educational groups in Australia Children in OOHC represent one of the most disadvantaged educational groups in Australia (NSW Department of Communities and Justice, 2020b). There is an abundance of research associating placement in OOHC with lower levels of educational engagement, satisfaction and achievement when compared to other children.

In comparison to their peers, Children in OOHC on average:

- Have lower overall educational achievement including in literacy and numeracy (Department of Education and Training, 2021; Townsend et al., 2022);

- Have poorer mental wellbeing (Baldwin et al., 2019);

- Have increased vulnerability to behavioural problems and mental health challenges in the future (Ryan, 2007);

- Are disproportionately represented in special needs education and disability support programmes (Townsend et al., 2022);

- Have greater incidences of suspension and/or expulsion (Townsend et al., 2022);

- Are less likely to graduate from secondary school (Department of Education and Training, 2015, Townsend et al., 2022); and,

- Are less likely to have gained employment or engaged in postgraduate study six months after leaving school (Department of Education, 2021, Townsend et al., 2022).

Within North Queensland, the problem is particularly relevant to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, due to their significant over-representation in the child protection system (Department of Children, Youth Justice and Multicultural Affairs, 2022a). Data released by the Department of Children, Youth Justice and Multicultural affairs (2022b) indicates Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander children account for 55.5% of all children in OOHC, well above their population share of only 8%. Blackstock et al. (2020) argue a shortage of interventions that are culturally-based is contributing to this over representation. The unprecedented rate is reminiscent of Australia’s Colonial period that led to the Stolen Generations (Funston and Herring, 2016).

Causes

The causes of the pronounced disadvantage are complex and multi-faceted and can include among many others:

- Experiences of abuse, neglect and disrupted attachment;

- Separation and alienation from family;

- Placement instability (i.e. moving through multiple carer families);

- Educational instability (i.e. moving through multiple schools); and,

- Cultural barriers including disconnection from cultural identity and community.

The causes are interconnectedThe causes are interconnected, with the impacts of one or more of the risk factors described above often leading to others. Townsend and colleagues (2016) found that child protection history, socio-emotional wellbeing and educational outcomes are correlated. The following sub-sections outline three specific causal factors, which are particularly relevant to the proposed research hypothesis.

Placement Instability

A report from the 44th Parliament in 2015 determined one of the most significant factors contributing to positive outcomes for children in OOHC is placement stability. The report highlighted the importance of finding the right placements early (Frederico et al., 2017 & Parliament of Australia, 2015.a) and recommended a nationally consistent approach to permanency planning (Parliament of Australia, 2015b).

Foster care instability is common in Australia, with more than half of children in OOHC in Queensland having had at least two placements after two years or more (Australian Institute of Family Studies, 2021). This can exacerbate existing problems or potentially create behavioural and emotional issues where there were none before (Capps, 2012).

A child who experiences frequent placement changes early on is likely to continue to have placement breakdowns (Konijn et. al., 2021). Further, when a child is placed with a carer who has biological children, there is a greater chance of a placement breaking down (Guerney, 2003).

A ramification of placement instability and frequent breakdowns is that children in OOHC can have a lowered self-esteem. Morvitz and Motta (1992) found that irrespective of other variables, a child’s self-esteem is overwhelmingly correlated with their perception of how both paternal and maternal caregivers accepted them. Self-esteem developed early on has been shown to endure over time and may have implications for academic engagement (Bowden et al., 2021). Further, higher levels of parental involvement in a child’s education has been shown to decrease problematic behavioural issues (Wages, 2016).

Due to the increased behavioural and mental health needs of a child who has experienced trauma, it is recognised that caregivers for children in OOHC experience additional parenting challenges (Murray et al., 2011, Ryan, 2007). Carer distress increases the likelihood of a placement breakdown (NSW Department of Communities and Justice, 2020c) and can contribute to a placement breakdown (Konijn et. al., 2021) resulting in a lack of a continual carer and stable home environment for a child.

Educational Instability

Children in OOHC are more likely to experience a disrupted education, including more frequent school changes, due to limited availability of carers and their proximity to school (Department of Education and Training, 2015). Townsend et. al. (2016) argue that the transition from one educational setting to another increases the chances of negative outcomes when combined with a concurrent transition, such as family disruptions. It is therefore unsurprising that data from one NSW longitudinal study, showed one in five children who had been in OOHC for approximately five years or more indicated they only ‘sometimes’ or ‘rarely or never’ understand the work taught in class (NSW Department of Communities and Justice, 2020b).

Current practice in Queensland for supporting children in OOHC is centred around the development of individualised Education Support Plans (ESP) identifying student needs, goals and the support required to achieve them (Queensland Government, 2021). The 44th Parliament Report (2015) recommendation 17 emphasised the need for greater educational support and increased participation for children in OOHC. Additionally, recommendation 18 highlights the need for up-to-date education plans for all children in OOHC (Parliament of Australia, 2015.b).

CREATE Foundation, an organisation that acts as an independent voice for children in OOHC, released a report card series in which one interviewed child stated, “We need a stable environment. We need to know how to access things like tutoring, resources, and the library. We need as much encouragement from you as you can give” (CREATE Foundation, 2006).

Cultural Barriers

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in OOHC face unique cultural barriers which can impact their self-concept, wellbeing and in turn educational engagement and success. These can include a sense of loss, or disconnection from cultural identity and community including loss of family, language and community connections when not placed with kin. As of June 2021, only 37% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in OOHC in Queensland were placed with a Kinship carer (Department of Children, Youth Justice and Multicultural Affairs, 2022a), defined as an approved member of the child’s extended family or community, or where there is a significant pre-existing relationship Queensland Government (2022).

Impacts

Children in OOHC long-term have lower educational outcomes than their peers. Children who stay in OOHC for at least five years tend to have greater rates of behavioural problems and require support for their social and emotional well-being (NSW Department of Communities and Justice, 2020a). Children who encounter difficulties at school and with getting along with peers may also have greater rates of negative reactivity, persist less at school tasks and be more likely to disengage from schooling (NSW Department of Communities and Justice, 2020b).

Beyond but related to educational achievement, children with a history of OOHC are more likely to experience lower overall life outcomes such as decreased levels of housing stability and increased homelessness; poorer mental, physical and emotional well-being; higher rates criminal involvement; and higher morbidity (NSW Department of Communities and Justice, 2020a). Research indicates adults who were placed in OOHC as children are overrepresented in the homeless population, likely due to the difficulties in transition from dependence on the state to independent living (Roman & Wolfe, 1997).

Benefits of Addressing Concerns with Children in OOHC

To address the significant demonstrable impacts, there is a clear need to develop and implement more effective strategies to improve student well-being and educational engagement for children in OOHC. The causal factors identified indicate a specific need for strategies targeted toward intervention in the early education setting and which focus on strengthening the relationships between the child and caregiver to enhance placement stability, as both of these factors are critical to change the future trajectory of the child’s education (Brinkman et al., 2013; Draper et al., 2009).

Addressing the problem is expected to yield significant benefits for children in OOHC in terms of their immediate well-being and educational success at school, their overall life outcomes, and the outcomes of future generations. By supporting children to grow into independent, functioning and contributing members of society, addressing the problem is also expected to generate significant societal benefits. The avoided societal cost could be considerable, with one study estimating the lifetime cost of cases of child abuse and neglect in Australia first occurring in the year 2015 at approximately $6 billion, including all anticipated ongoing costs of OOHC, education, healthcare, housing, welfare and the justice systems (Parliament of Australia, 2015c).

Research Hypothesis

Given the breadth and complexity of the problem, a wide range of interventions will be required from institutional and policy reform at the national and state level, to detailed practical strategies and programmes to be implemented by key stakeholders in the lives of children in OOHC. It is critical these strategies are developed, tailored, and implemented to respond to the diverse circumstances faced by each child in OOHC.

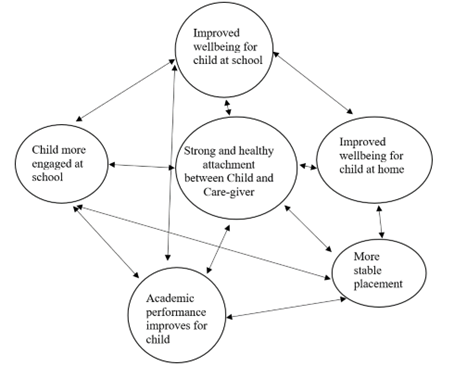

While there are a host of therapeutic services available to support those in OOHC, they frequently overlook support that strives to strengthen the connection between the child and their carer family (Gilmartin & McElvaney, 2020). The connection is vital to maintaining placement stability and improving child-wellbeing, educational engagement and academic success as illustrated in Figure 1.

Filial Therapy (FT) is one effective strategy to strengthen the connection between the child and carer family and child and school, facilitate a stronger level of commitment and academic support from carer families, enhance the child’s self-concept and esteem and may thereby facilitate better educational engagement and outcomes for children in OOHC. There is a strong research base demonstrating the effectiveness of FT in addressing child and family problems (Gilmartin & McElvaney, 2020), and it is hypothesised that the technique could be adapted for specific application by suitably trained Primary School Guidance Officers in a school setting to benefit children in OOHC.

The proposed research project is centred on this hypothesis and seeks to address the question ‘Can Filial Therapy in early education settings improve student well-being and educational engagement for children in long-term out-of-home care? ‘Can Filial Therapy in early education settings improve student well-being and educational engagement for children in long-term out-of-home care?

The outcome of this research is anticipated to form the foundations of a school-based Filial Therapy (SBFT) programme, to be implemented by Primary School Guidance Officers in North Queensland, and further afield.

Existing Research

While there are no examples of direct research into the efficacy of Filial Therapy (FT) applied in a school setting to improve well-being and educational engagement for children in long-term OOHC in North Queensland, many related studies have been undertaken from which lessons can be drawn. The following sub-sections summarise relevant findings from existing research across the key research themes.

Filial Therapy

FT was designed in the 1960s by Child Psychologist Dr Bernard Guerney to strengthen families through the use of play. It is underpinned by a core belief that the power of therapeutic change lies in shared responsibility between the child, the child’s parents, their child-parent relationship and the actions of play itself (Guerney, 2003).

FT draws on elements of family therapy and non-directive play and aims primarily to establish secure attachments, strengthen relationships and avoid family disruptions (Barrett, 2022). It involves training the parent or caregiver as therapeutic change agents (Ryan, 2007), enabling them to then conduct a series of non-directive play sessions with the child within a framework of support from a qualified play therapist.

A significant research base has been established over many years demonstrating FT as an effective therapeutic intervention to address a range of child and family problems including child and family trauma, bereavement and domestic violence (Gilmartin & McElvaney, 2020). While initially developed and researched predominantly in North America, many recent studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of FT in varied geographic and cultural contexts across the world, including in Australia.

Filial Therapy Applied to Children in Out-of-Home Care

The focus of FT on developing strong relationships between the child and caregiver, makes it particularly suitable for children and young people in OOHC. Utilisation of non-directive play techniques, which create an atmosphere of safety and enable children to address prior trauma through play, make FT suitable for maltreated children who find it difficult to trust adults (Jee et al., 2014). FT also assists carers to develop stronger and more adaptive relationships with their children, which has been found to reduce carer stress levels and improve their caregiving response (Ryan, 2007).

Gilmartin & McElvaney (2020) present a summary of the evidence base, and the core elements which underpin FT’s suitability in the area of foster care. The study argues the combination of the following key factors differentiate FT from other play-centred child-parent interventions and make it uniquely effective for working with children in OOHC and their carer families (Gilmartin & McElvaney, 2020):

- A focus on the carer–child relationship rather than child as ‘the client’, thereby avoiding framing the child as the problem.

- Utilisation of non-directive play which mimics the healthy interactions which normally occur in infancy between parent and child and promotes the development of secure attachment (Ryan and Wilson, 1995).

- Involvement of all family members where possible which can enhance placement stability, particularly where carer families have other biological children.

- A focus on felt empathy to assist children in learning self-acceptance and develop their own empathy skills and well-being.

- Fostering of collaborative partnerships between the carer families, therapist and other stakeholders in the life of the child.

Ryan (2007) sets out the rationale and benefits of employing FT with maltreated children and children in OOHC, highlighting the advantages of similar characteristics to those listed above. The study presents a series of case vignettes to demonstrate the suitability of FT to children in OOHC with varied needs including a late adopted child, a young ‘looked after’ child with serious attachment difficulties, an older child in a specialist foster placement, and a child on the autistic spectrum in an adoptive placement. The study concludes that FT can be an effective strategy for children in care experiencing a range of problems.

Ryan (2007) also highlights the need for further research to understand effectiveness and adaptations required:

- In different settings such as residential care, health and education settings (including mainstream and special needs schools);

- Using different delivery methods (such as shorter versus longer programme durations, one carer versus two carers, one child versus all children); and,

- With different professional involvement (such as key workers as filial therapists compared with teachers).

While FT has traditionally been applied with younger children, Capps (2012) explores its application as a means of strengthening relationships between carers and adolescent children in OOHC. The study demonstrates that with appropriate adaptation to reflect the specific needs and developmental stage, FT can also be effective for older children in OOHC.

Filial Therapy Applied in a School Setting

Cooper and Oliaro (2019) designed and implemented a school-based Filial Therapy (SBFT) programme for delivery by teachers, school learning-support officers, and teacher’s aides, for primary-school children in Regional and Remote New South Wales. The study highlights a range of lessons directly applicable to the proposed research, including methods to address barriers to the application of FT:

- In school settings – including the staffing, resources and management support required to avoid service access issues (Cooper, et al., 2022a); and

- In regional and remote communities with high indigenous populations – including condensing training programmes to a shorter timeframe which is more achievable for both the school and supporting professionals given the long travel distances involved and ensuring culturally appropriate communication.

The study deemed FT in school settings to be efficacious, and delivery by paraprofessionals to be an effective means of intervention. It highlights the need for the design of SBFT programmes that are flexible and can be adapted to suit the specific cultural, resources and local complexities faced by each community, school and client. It also concluded that a uniform approach to implementation in all contexts would not be effective and would not harness the value of individual community capacity to meet its own needs.

Cooper and Oliaro (2019) highlighted key gaps requiring further research including the pilot:

- Relates specifically to rural and remote populations and further research is required to determine whether the conclusions can be extrapolated across a wider geographical region;

- Involved implementation by teachers and paraprofessionals, and further research is required to examine facilitator barriers and the potential benefits from training both the school staff and caregivers (Cooper et al., 2022b); and,

- Was limited to a 10-week duration, and further research and piloting over a longer duration is required to provide a longitudinal perspective on child outcomes.

FT has also been adapted into school settings utilising older students as the therapeutic agents. In one study by Jones et al. (2002), high school students were trained to assist kindergarten children adjust to school. Although limited by a small sample size and possible bias of parents and teachers, the study concluded that FT delivered by older children can be effective and contribute to reducing problematic behaviours in younger children.

Filial Therapy Applied to First Nations Children

In compiling this literature review, no research was identified specifically exploring the application of FT with Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander children in Australia.

Boyer (2011) discusses the application of a FT method called child-parent relationship therapy in response to working with a First Nation child and his Kin carer, an ‘urban Aboriginal’ residing in a large midwestern city in Canada. To assess the effectiveness of the therapy, Boyer used the Marschak Interaction Method (a tool used to evaluate and observe the child-parent relationship (Bojanowski, 2005)) and systemic observations and reflections of videotaped sessions. In summary, the study found FT assisted the Kin-carer in honouring his ancestors and elders by implementing the core values of his First Nations traditional parenting.

Lessons from this research may be used to inform cultural considerations in the design of the proposed research, as well as methods to assess the impacts of FT on the child-carer relationship; however, the significant differences in the cultural contexts will need to be considered.

Considerations for Future Research

There is a strong research base within some of the key thematic areas (such as the effectiveness of FT applied with children in OOHC); however, there is less research in other areas (such as the effectiveness of FT applied with First Nations children). There also appears to be a distinct gap in existing research when it comes to the application of FT within a school-based setting in combination with students in OOHC, particularly when considered within the unique North Queensland context.

Table 1 summarises the key gaps identified, the significance of the gaps, and their implications for the design of the proposed research project.

Table 1: Gaps and considerations for future research

| Aspect | Existing Research and Gaps | Significance | Considerations for Proposed Research |

| Location |

|

|

|

| Impact of FT on educational engagement and wellbeing |

|

|

|

| OOHC context |

|

|

|

| Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander context |

|

|

|

| FT in the school setting |

|

|

|

| Length of SBFT programmes |

|

|

|

Conclusion

The causes of disadvantage faced by Children in OOHC are complex and multi-faceted, however, broadly all contribute to children having poorer mental well-being and lower levels of educational engagement (Baldwin et al., 2019). This adversely impacts their educational achievement throughout schooling and contributes to poorer overall life outcomes (NSW Department of Communities and Justice, 2020a). Given the significance of the problem, there is a clear need for fit-for-purpose intervention strategies targeted toward improving educational engagement and well-being for children in OOHC.

This literature review has been prepared to inform the design of a research project which seeks to investigate the effectiveness of FT, applied in an early education setting, to improve the well-being and educational engagement of children in long-term out-of-home care in North Queensland, Australia. It has provided an analysis of the cause and impacts of the educational disadvantage faced by children in OOHC, the rationale for the proposed research hypothesis, and a summary of relevant research into the effectiveness of FT generally, applied to children in OOHC, applied in a school setting and applied with First Nations Children in Australia and overseas.

The literature review supports the research hypothesis, indicating the application of FT in an early education setting may improve student well-being and educational engagement for children in long-term OOHC. It has also identified key gaps within available literature, which need to be further investigated as part of the proposed research project. These gaps largely relate to a lack of evidence on the effectiveness of FT applied within a school-based setting in combination with students in OOHC, particularly within the unique North Queensland context.

References

Australian Institute of Family Studies. (2021). What contributes to placement moves in out-of-home care? (No. 61). Australian Government. https://aifs.gov.au/sites/default/files/publication-documents/2107_cfca_61_what_contributes_to_placement_moves_in_out-of-home_care_0.pdf

Barrett, H. (2022). Filial family therapy. https://www.helenbarrett.com.au/filial-family-therapy/

Baldwin, H., Biehal, N., Cusworth, L., Wade, J., Allgar, V., & Vostanis, P. (2019). Disentangling the effect of out-of-home care on child mental health. Child Abuse & Neglect, 88, 189–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.11.011

Blackstock, C., Bamblett, M., & Black, C. (2020). Indigenous ontology, international law and the application of the Convention to the over-representation of Indigenous children in out of home care in Canada and Australia. Child Abuse & Neglect, 110(Pt 1), 104587–104587. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104587

Bojanowski. (2005). Discriminating between pre- versus post-Theraplay® treatment Marschak® Interaction Methods using the Marschak® Interaction Method Rating System. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

Bowden, J. L.-H., Tickle, L., & Naumann, K. (2021). The four pillars of tertiary student engagement and success: A holistic measurement approach. Studies in Higher Education, 46(6), 1207–1224. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1672647

Boyer. (2011). Using child parent relationship therapy (CPRT) with our First Nations people. International Journal of Play Therapy, 20(1), 38–49. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022650

Brinkman, Gregory, T., Harris, J., Hart, B., Blackmore, S., & Janus, M. (2013). Associations between the early development instrument at age 5, and reading and numeracy skills at ages 8, 10 and 12: A prospective linked data study. Child Indicators Research, 6(4), 695–708. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-013-9189-3

Capps. (2012). Strengthening foster parent–adolescent relationships through Filial Therapy. The Family Journal, 20(4), 427–432. https://doi.org/10.1177/1066480712451245

Cooper, & Oliaro, L. (2019). School-based Filial Therapy in regional and remote New South Wales, Australia. International Journal of Play Therapy, 28(1), 34–43. https://doi.org/10.1037/pla0000085

Cooper, J., Brown, T., & Yu, M. (2020). A pilot study of school-based Filial Therapy (SBFT) with a group of Australian children attending rural primary schools: The impact on academic engagement, school attendance and behaviour. International Journal of Play, 9(3), 283–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/21594937.2020.1806495

Cooper, Yu, M., & Brown, T. (2022a). Occupational Therapy Theory and school-based Filial Therapy: Intervention rationale and formulation. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy (1939), 89(1), 62–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/00084174211056588

Cooper, Yu, M., Brown, T., & MacKay, L. (2022b). An exploratory study of facilitator adherence to a School-Based Filial Therapy programme. International Journal of Play, 11(2), 145–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/21594937.2022.2069349

CREATE Foundation (2006). Report Card on Education 2006. https://create.org.au/research-and-publications/

Department of Children, Youth Justice and Multicultural Affairs. (2022a). Child safety policy: Structured decision making, policy no: 407-7. https://www.cyjma.qld.gov.au/resources/dcsyw/protecting-children/structured-decision-making-407.pdf

Department of Children, Youth Justice and Multicultural Affairs. (2022b). Our Performance: Over-representation in the child protection system. https://performance.cyjma.qld.gov.au/?domain=4ng99xeqmb60&subdomain=5iq7j3pc2eg0

Department of Education and Training. (2021). Students in out-of-home care policy statement. https://education.qld.gov.au/students/student-health-safety-wellbeing/students-with-diverse-needs/students-out-home-care-policy

Department of Education and Training. (2015). Research overview: Children in out-of-home care. https://education.qld.gov.au/student/Documents/research-overview-students-in-out-of-home-care.doc

Department of Queensland. (2018). Types of Childrens Court orders. https://www.qld.gov.au/community/caring-child/foster-kinship-care/information-for-carers/rights-and-responsibilities/legal-matters/types-of-childrens-court-orders

Draper, K., Siegel, C., White, J., Solis, C. M., & Mishna, F. (2009). Preschoolers, parents, and teachers (PPT): A preventive intervention with an at risk population. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy, 59(2), 221–242. https://doi.org/10.1521/ijgp.2009.59.2.221

Ebrahimi, Mirzaie, H. H., Saeidi Borujeni, M. M., Zahed, G. G., Akbarzadeh Baghban, A. A., & Mirzakhani, N. N. (2019). The effect of Filial Therapy on depressive symptoms of children with cancer and their mother’s depression, anxiety, and stress: A randomized controlled trial. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention : APJCP, 20(10), 2935–2941. https://doi.org/10.31557/APJCP.2019.20.10.2935

Frederico, Long, M., McNamara, P., McPherson, L., & Rose, R. (2017). Improving outcomes for children in out‐of‐home care: The role of therapeutic foster care. Child & Family Social Work, 22(2), 1064–1074. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12326

Funston, L., & Herring, S. (2016). When will the Stolen Generations end? A qualitative critical exploration of contemporary “child protection” practices in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. Sexual Abuse in Australia and New Zealand, 7(1), 51–58.

Gilmartin, D., & McElvaney, R. (2020). Filial Therapy as a core intervention with children in foster care. Child Abuse Review, 29(2), 159–166. https://doi.org/10.1002/car.2602

Guerney, L. (2003). Filial Play Therapy. In C. E. Schaefer (Ed.), Foundations of Play Therapy (pp. 99 -142). John Wiley

Jee, S. H., Conn, A.-M., Toth, S., Szilagyi, M. A., & Chin, N. P. (2014). Mental health treatment experiences and expectations in foster care: A qualitative investigation. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 8(5), 539–559. https://doi.org/10.1080/15548732.2014.931831

Jones, L., Rhine, T., & Bratton, S. (2002). High school students as therapeutic agents with young children experiencing school adjustment difficulties: The effectiveness of a Filial Therapy training model. International Journal of Play Therapy, 11(2), 43–62. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0088864

Konijn, Colonnesi, C., Kroneman, L., Lindauer, R. J. L., & Stams, G.-J. J. M. (2021). Prevention of instability in foster care: A case file review study. Child & Youth Care Forum, 50(3), 493–509. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-020-09584-z

Morvitz, E., & Motta, R. W. (1992). Predictors of self-esteem: The roles of parent-child perceptions, achievement, and class placement. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 25(1), 72–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/002221949202500111

Murray, L., Tarren-Sweeney, M., & France, K. (2011). Foster carer perceptions of support and training in the context of high burden of care: Foster carer support and training. Child & Family Social Work, 16(2), 149–158. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2206.2010.00722.x

NSW Department of Communities and Justice. (2020a). Developmental outcomes: Children and young people who have experienced out-of-home care. Pathways of Care Longitudinal Study: Outcomes of Children and Young People in Out-of-Home Care. Evidence to Action Note Number 8. Sydney. NSW Department of Communities and Justice. https://www.facs.nsw.gov.au/download?file=821620

NSW Department of Communities and Justice. (2020b). Educational outcomes: Children and young people in out-of-home care. Pathways of Care Longitudinal Study: Outcomes for Children and Young People in Out-of-Home Care. Evidence-to-Action Note Number 5. Sydney: NSW Department of Communities and Justice. https://www.facs.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/813820/Educational-outcomes-children-and-young-people-in-out-of-home-care.-Pathways-of-Care-Longitudinal-Study.-2021.-Evidence-to-Action-Note-Number-5.PDF

NSW Department of Communities and Justice (2020c). Placement Stability: Children and Young People in OOHC. Evidence to Action Note Number 7. Sydney. NSW Department of Communities and Justice. https://www.facs.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0011/813818/Placement-stability-children-and-young-people-in-out-of-home-care.-Pathways-of-Care-Longitudinal-Study.-2021.-Evidence-to-Action-Note-Number-7.PDF

Parliament of Australia (2015a). Report: Out of home care, chapter 4: Outcomes for children and young people in out-of-home care. https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate/Community_Affairs/Out_of_home_care/Report/c04

Parliament of Australia (2015b). Report: Out of home care, list of recommendations. https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate/Community_Affairs/Out_of_home_care/Report/b01

Parliament of Australia (2015c). Report: Out of home care, chapter 1, Introduction. https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate/Community_Affairs/Out_of_home_care/Report/c01

Queensland Government. (2022). Foster carers. https://www.cyjma.qld.gov.au/campaign/foster-care-recruitment?gclid=CjwKCAjw7eSZBhB8EiwA60kCWzlv-qveGpuGU0IQxJZ6hDXQM27LF2ti4yhJV0BX91Xib0XI8KbGCBoCZ1IQAvD_BwE

Queensland Government. (2021). Young people in care: Education support plans. https://www.qld.gov.au/youth/social-support/young-people-in-care/education-support-plans

Roman, N. P., & Wolfe, P. B. (1997). The relationship between foster care and homelessness. Public Welfare, 55(1), 4–9.

Ryan, V. (2007). Filial Therapy – helping children and new carers to form secure attachment relationships. The British Journal of Social Work, 37(4), 643–657. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bch331

Ryan, V., & Wilson, K. (1995). Non-directive play therapy as a means of recreating optimal infant socialization patterns. Early Development & Parenting, 4(1), 29–38. https://doi.org/10.1002/edp.2430040105

Smith, O’grady, L., Cubillo, C., & Cavanagh, S. (2017). Using culturally appropriate approaches to the development of KidsMatter resources to support the social and emotional wellbeing of Aboriginal children. Australian Psychologist, 52(4), 299–305. https://doi.org/10.1111/ap.12284

Townsend, Reupert, A. E., & Berger, E. P. (2022). Educators’ experiences of an Australian education program for students in out-of-home care. Child & Youth Services. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/0145935X.2022.2046461

Townsend, M. L., Cashmore, J., & Graham, A. (2016). Education and out-of-home care transitions. Developing Practice: The Child, Youth and Family Work Journal, (45), 71–85. https://ro.uow.edu.au/sspapers/3228/

Wages, M. (2016). Parent involvement: Collaboration is the key for every child’s success. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.