11. Empowering Higher Degree Researchers’ Career Planning

Alan McAlpine

Why read this chapter?

From this chapter you will learn:

- to best support the future career needs of your higher degree research (HDR) students

- about frameworks/theories that describe career development

- to have a conversation in a student-centred way

- to help your students broaden their possible future opportunities.

As supervisors, chances are that the majority of your career has been primarily in an academic role. You may view your purpose as supervisors to encourage, educate, and train the next wave of career academics. This is an admirable goal and a very important part of your role. However, the reality is that your higher degree researchers (despite their current desires) may not become academics; indeed, the statistics show (see Table 11.1) that more will end up in non-academic roles. Many will secure opportunities in industry (indeed they may have come from industry and intend to return with their newfound research skills), and some may even venture into producing start-up ventures. Others may end up working in local, state, or federal government jobs utilising the strong critical thinking skills they have acquired. A number will end up in roles that have nothing to do with the discipline for which they are currently being trained. As supervisors and mentors to higher degree researchers, you can open their eyes to the multiple pathways (which include academic roles) that a research degree can provide. However, this does not mean you need to have, or provide, all the answers. You can enable higher degree researchers to use their current studies as the stepping stone to whatever future they desire, to keep them motivated through research degree studies, and to use challenges as opportunities for skills development and rely upon and use to become independent researchers pursuing career futures.

| Year | HDR grads in employment | HDR Grads employed in higher ed | % HDR Grads employed in higher ed |

| 2018 | 5163 | 2413 | 47% |

| 2019 | 5278 | 2416 | 46% |

| 2020 | 5238 | 2609 | 50% |

| 2021 | 4827 | 2323 | 48% |

| 2022 | 5045 | 2309 | 46% |

| Total | 25551 | 12070 | 47% |

This chapter offers some tips and techniques for supervisors working with higher degree researchers on empowering them to find their own pathways and to value the role of their studies in progressing their future careers. These ideas can have relevance for higher degree researchers, and early career researchers working with supervisors as they seek to pursue career futures.

The higher education sector has encountered a huge increase in the number of students undertaking research degrees and increases in academic roles have not kept pace… this should not discourage the higher forms of formal education. Doctoral completions are good for our economy as a whole and offer higher degree researchers’ multiple options and pathways (Casey, 2009). We have invested in their education, why would we not invest in their future? It will pay back dividends to society as a whole.

Career development – What is it and why is it important?

The majority of us have careers and so we may believe we are experts in career development. This statement may only be partly true. We often believe that our experience is the only experience; however, if we have a conversation with our networks, we will find that all our experiences are unique.

Like any other skill or attribute, if we can access tools, develop techniques, and practice these skills we can become more accomplished in their use. At a basic level some of the key features of career development are:

- Understanding self, skills, and qualities.

- A career comprises everything we do, not just paid employment.

- Understanding the job market (in and beyond the current field of study).

- Developing job searching strategies.

- Building networks and connections.

- Seeking out mentors.

So, in a certain way of thinking about it, Career Development is a process. As supervisors, your role is not to provide the answers or assume you know what the future direction of your higher degree researchers will be (you may have a view), but to support them in applying the process. Supervisors can be a starting point for higher degree researchers in building networks and as their mentors. One of the biggest challenges higher degree researchers may face is that they have become very specialised in their research, and so can struggle to see the big picture. This big picture can help those seeking opportunities outside of their research specialisation or outside of academia.

All of this can provide a strong foundation for higher degree researchers as they begin to navigate the ever-changing world and find their career pathway.

The world of work in the 21st Century is highly complex and continually evolving. The impact of technology has made the possibilities of work both more exciting and challenging. Many of the jobs that higher degree researchers will take up in the future have possibly not yet even been imagined.

In this VUCA (Volatile, Uncertain, Complex and Ambiguous) world, career resilience has become far more important (Bennis & Nannus, 2007). Lyons et al. (2015) demonstrated the growing importance of career resilience within career development interventions, proposing it as a way of coping with the challenges the new world of work is throwing at us. Thus, it is highly likely that today’s higher degree researchers will come across numerous challenges that they are required to overcome. As supervisors, you can, through discussion, support your students to unpack these challenges and help them apply coping and problem-solving skills they are developing to move forward. These experiences and skills will all inform their future career progression.

Career frameworks

In the career world, there is no overarching unifying theory. Numerous theories and frameworks continue to evolve in response to the dynamic world of work. Early in the development of Career Theory, Parsons & Wigtil (1974) showed that individuals could be matched to groups of occupations based upon certain personality traits. While certain parts of this theory still hold true (the personality of a person often will determine what occupational types are attractive to them), the interactions that guide a person in a particular career direction have been shown to be far more complex.

Here I briefly describe a well-known, and commonly referenced/used, framework (Systems Theory Framework) and a theory (Chaos Theory) that I hope can guide and inform supervisor’s conversations with higher degree researchers. My intention here is not to create career development experts or advisors but simply to provide and inform some of the practices for working with higher degree researchers to realise their research independence and career direction.

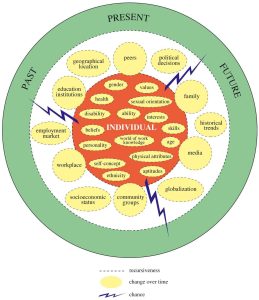

Systems Theory Framework (STF)

The Systems Theory Framework (STF) as outlined by Patton & McMahon (2006) brings together several theories and models of career development. It acknowledges that an individual’s life and career choices are influenced by many and varied factors. It puts the individual at the centre of the framework and recognises the interpersonal concepts that can influence that person. It is important to note, at this point, that often in non-Western cultures this may not be the case; in some instances, collectivist cultures, the value of group, community or family is viewed as more important than that of the individual in a decision-making process. It is worth keeping this in mind when working with higher degree researchers from cultural backgrounds that may be different from your own.

The framework includes the influence of external factors in the decisions an individual may make and opportunities available to them, e.g., current socio-economic situation, geographical location, etc. It then considers the influence of past, present, and future experiences, because the importance of certain factors are likely to change over time.

The occurrence of chance also plays a factor in an individual’s influences, and, as Chaos theory shows, we can take advantage of this too.

Chaos theory of careers

This theory as outlined by Pryor & Bright (2011) takes account of the fact that we live in a world that is both stable and constantly changing. It recognises that while we cannot control the chance events that occur in our world, we can take proactive actions to take advantage of chance events when they happen. We can still plan.

This theory proposes that trying different things and pushing ourselves outside of our comfort zone helps generate the occurrence of more chance events, and so opportunities. The trick is then to be able to recognise which opportunities fit with our desires, plans, and future aspirations. Self-awareness is everything.

I have introduced two of the many theories in career development. A simple Google search will identify numerous others. The two briefly outlined here provide an overarching framework to support supervisors in conducting career conversations with higher degree researchers. But they need to be applied in a conversational way – you cannot simply provide your higher degree research student with the theories alone.

Your practice

When to have a career conversation

It is never too late, or too early, to have a career conversation with a higher degree researcher. For some individuals a formal, regular conversation might be more appropriate (e.g., once per year, or every 6 months), where there is a date set and expectations are clear prior to the conversation. For other higher degree researchers, ad-hoc, unplanned conversations may arise when supervisors (and possibly they) least expect it. Supervisors need to be well prepared to make the most of both of these opportunities.

The term of a research degree in proportion to the length of a career is very short. With some good and deliberate career conversations, supervisors can set up higher degree researchers with the foundations for the rest of their careers.

How to have a ‘narrative’ conversation

Narrative Therapy is a counselling technique that puts the individual as the expert in their own lives (Ackerman, 2017). Often supervisors are in a position of power as higher degree researchers come to them for advice. Supervisors can feel pressured to provide all the answers for them. A narrative conversation is one where supervisors can empower higher degree researchers to make decisions based upon their own experiences and expertise based more firmly in the realities of their lives. A narrative conversation seeks to ‘externalise’ the issue at hand and encourages the individual to seek other ‘narratives’ that best describe and deal with the issue or challenge.

This approach seeks to open the conversation up using open questioning techniques and seeks to investigate strengths in the individual to best tackle the challenges presented. The conversation may result in some homework where higher degree researchers apply their practice of going off and conducting research to find ways of tackling the issue at hand that can be discussed later with their supervisors. For example:

Higher Degree Researcher – “My issue is that this is all too hard. I don’t have the ability to work through this problem and I don’t have the right skills and knowledge.”

Supervisor – “So there is a challenge, and you need to find the right tools to help solve it. What tools do you usually rely on when things get tough?”

The tendency (or the strong desire) to provide solutions can be overwhelming for some supervisors in conversations with higher degree researchers. The narrative conversation does not preclude providing advice or ideas; however, it has to be undertaken in a way that provides choice and empowers higher degree researchers.

“What I suggest you do here is…”

The following may provide alternative approaches to the conversation:

“Have you thought about other ways you might approach this matter?”

“What other ways have you thought about this?”

“I wonder who else you could talk to about this who may have had a similar experience?” (Creates action).

If you did wish to share an example from your own experience, then:

Case study

A higher degree researcher approaches a supervisor regarding future opportunities. They are a local higher degree researcher and have recently become aware that the future research opportunities (in their specialisation) are all overseas. They have close family ties locally, and have no great desire to leave the local area to pursue.

Supervisor – What interested you in your topic area in the first instance?

Higher Degree Researcher – The topic area is of great interest personally, and I was keen to pursue a research degree.

Supervisor – Why was the topic of particular personal interest?

Higher Degree Researcher – The desire to make a difference in people’s lives in my community.

Supervisor – That is an admirable motivation. What have you learned about yourself through doing research studies?

Higher Degree Researcher – That it can be a long slow process to break new ground, that the impact upon the field can take a while.

Supervisor – What skills have you developed in undertaking research?

Higher Degree Researcher – patience, persistence, resilience….

Supervisor – Where else, locally, could you apply those skills?

Higher Degree Researcher – I am not sure?

Supervisor – Given your passion for making a difference locally, in your topic area, I wonder where else you could apply those qualities.

Higher Degree Researcher – Mmm, not sure. Maybe there are some local businesses I could apply to.

Supervisor – True. I wonder who you could chat with first before looking for specific work?

Higher Degree Researcher – Yeah. Maybe I could ask my cousins who work in some of those areas?

Supervisor – That sounds like a great plan.

Some useful tips

- Learn and practice how to have a ‘narrative’ conversation. Ask your colleagues and higher degree researchers to tell their stories.

- Try not to be an advice giver; learn and practice to do this in a way that provides the student with a choice.

- Give the benefit of your experience (it is valuable).

- You cannot be what you cannot see (much used in the equity space, but valid in all – from a careers perspective, that is seeing the types of roles you would like to engage with or making contacts to build experience or networks).

- The importance of understanding what the student’s underlying motivator may be, e.g., perhaps they have had a parent who suffered from a particular ailment, and this is the presenting motivator for undertaking the current research. This is a valid motivator, however there may be other ways to meet this important and inherent need.

- Validate higher degree researchers’ thinking.

- For some the motivation to find gainful employment may be the driving force…and that is OK.

- Refer to career experts (your university may/should have a career service – if not, there are plenty of resources to be found online).

Mentoring and networking

The use of mentors from industry and broader disciplinary networks to build effective networks is an extremely useful way of helping higher degree researchers. Mentors can provide other voices into the career conversation as well as links to opportunities that higher degree researchers may not yet have considered. Supervisors will have many other networks to offer as well (maybe you haven’t considered how wide your own network is – other academics, industry partners, etc.) The often-used catchcry of ‘It’s not what you know but who you know’ holds some truth but is only partly correct. It is both “what you know” and “who you know” that is important. The creation of networks, both large and small, feeds into the Chaos Theory model mentioned earlier, and opens both untapped and unimagined opportunities. As supervisors, you can show higher degree researchers how to leverage contacts to develop new networks and mentors. It is important that higher degree researchers learn to engage with new contacts, rather than supervisors directly handing them over to possible contacts. Building higher degree researchers’ abilities and confidence in proactively reaching out is another valuable skill for them to develop. Encouraging higher degree researchers to join student clubs and professional associations will also help them to develop skills and build their network. Supervisors can monitor the success, or otherwise, of higher degree researchers in making a connection and this can be monitored during career conversations.

Applying this to your practice

Now is your opportunity to practice some of the techniques:

- Arrange a Career Conversation with one of your higher degree researchers.

- Prepare by setting out some broad questions to help guide your thoughts in the conversation.

- Consider some questions that allow the higher degree researcher to understand what may be influencing their decision-making process (influencers). Ask them to decide on at least one action to take.

- Take time to reflect on the conversation afterwards:

- What appeared to work well?

- What might you choose to change?

- What in particular did you notice about the higher degree researcher’s story?

- Did it fit with any particular framework introduced here?

- What, if any, were the particular motivations or influencers on the higher degree researcher’s decision(s)?

- Arrange a follow up conversation and hear about what happened with any agreed actions.

Conclusion

This chapter has been written to provide supervisors with practices in supporting higher degree researchers in pursuing future careers. The world of work is rapidly changing and the many and varied opportunities that they have before them can be overwhelming, some of which we probably haven’t even as-yet imagined. Supervisors are supporting the best and brightest in our community – higher degree researchers are the most highly educated cohorts in our country and world. These frameworks and approaches are intended to help supervisors to provide the best support they can to succeed in their future careers.

Additional Resources

While most of these sources and additional readings are freely available, some are not. The lock icon ![]() beside an entry indicates that the source may be available from your library.

beside an entry indicates that the source may be available from your library.

References

While most of these sources and additional readings are freely available, some are not. The lock icon ![]() beside an entry indicates that the source may be available from your library.

beside an entry indicates that the source may be available from your library.

Ackerman, C. E. (2017). 19 best narrative therapy techniques and worksheets. Positive Psychology.com. https://positivepsychology.com/narrative-therapy/

Casey, B. H. (2009). The economic contribution of PhDs. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 31, 219-227.

Bennis, W. & Nanus, B. (2007). Leaders: Strategies for taking charge (2nd ed.). Harper Business Essentials.

Lyons, S. T., Schweitzer, L. & Ng, E. S. W. (2015). Resilience in the modern career. Career Development International, 20(4), 363-383.

Parsons, G. E. & Wigtil, J. V. (1974). Occupational mobility as measured by Holland’s theory of career selection. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 5(3), 321-330.

Patton, W. & McMahon, M. (2006). The systems theory framework of career development and counselling: Connecting theory and practice. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling 28(2), 153-166.

Pryor, R.G.L. & Bright, J. (2011). The chaos theory of careers. Journal of Employment Counselling, 48(4), 163-166.

Quality Indicators for Learning and Teaching. (2023). 2022 graduate outcomes survey. Australian Government Department of Education. https://www.qilt.edu.au/docs/default-source/default-document-library/2022-gos-national-report.pdf?

Trevor-Roberts. (2021). 5 tips on how to have a career conversation with your employees that is effective and meaningful. https://blog.trevor-roberts.com.au/how-to-have-a-career-conversation