13. Supervising for Societal Impact: A Holistic Approach to Higher Degree by Research Support

Wade Kelly and Lisa M. Given

Why read this chapter?

Universities, governments, and funders are increasingly asking researchers to articulate how their work will produce a positive impact on society. Yet, many supervisors (and their higher degree researchers) have not been trained to communicate their work beyond academe, or to consider how their research can contribute to both immediate and longer-term societal change, beyond the scholarly contributions of their research. This societal impact imperative requires new approaches to the supervision of higher degree researchers, to best position them for future success. This chapter explores how to move beyond considerations related to preparation for thesis-related research work, to adopt a holistic approach to supervision that prepares higher degree researchers for societal impact work. Whether higher degree researchers wish to pursue careers in academe, or in industry, government, or community settings, embedding external engagement and impact-related skills throughout the journey will position them for success.

Introduction

We have all heard horror stories of poor research supervision; those supervisors who only met with their higher degree researchers during milestone meetings refused to provide feedback on writing, furnished no introductions, made no connections, and provided no encouragement. Sadly, the list of poor supervision stories is long and, occasionally, dark. Graduate supervision is a critical aspect of the academic mentoring process that should extend far beyond the context of providing support for thesis development but, too often, does not.

The core of the problem may be attributed to a lack of communication about and preparation for the responsibilities of supervisors. Supervisory training is increasingly common for new academics, but even seasoned supervisors need guidance to respond to particular situations and challenges their higher degree researchers may face. Professional development and mentoring beyond early career training is limited. This leaves too many supervisors to replicate their own (often poor) supervisory experiences and fail to adapt to rapid and ongoing changes in higher education. The higher degree experience of ten years ago is not the higher degree experience of today. The job market and the sector are different, and the skills required to flourish must evolve.

While this chapter focuses on preparing higher degree researchers for generation of societal impact, in their future work, the approach we advocate will also enable you to respond to other, new changes in the graduate experience by adopting a holistic style of supervision. That is, we look at the higher degree researcher as a whole person and address how best to support your higher degree researchers for success based on their desires and career aspirations. The thesis is an artefact; the higher degree is a future. To prepare higher degree researchers for their future, an evolving dialogue throughout the higher degree journey will focus on their activities, skills, knowledge, connections, and potential to generate societal impact, which will serve them well beyond graduation.

As researchers transition from their higher degrees into practice environments, they need to understand how to meaningfully engage beyond academe. In this chapter, we explore the significance of supervising for societal impact and discuss strategies to integrate this approach into graduate research programs.

The research landscape

The landscape of higher education is changing rapidly. Funders are increasingly requiring researchers to respond to specific requirements aimed at generating impact in their communities, with industry, or with government, throughout the research process. In this chapter, we refer to this as societal impact work to distinguish it from the scholarly impact of research (e.g., h-index and citations). Many funders now include societal impact statements as part of the application process; and universities have responded by offering sessions to higher degree researchers on crafting these statements for thesis work. However, to prepare higher degree researchers appropriately, we must move beyond instruction in the genre of writing impact statements, to fully embrace a societal impact mindset.

A good (societal) impact statement is the icing on the (research) cake. Funders are moving from asking about the icing to critically questioning how the cake was made, who was involved in making it, where the ingredients were sourced, how big the slices are, who is getting a piece, how it is being delivered, the costs involved, and whether a cake is the correct end-product, at all. Calls for co-design of research problems, participatory methods, co-production of solutions, and co-funding of research activities, position external beneficiaries of university research at the heart of the enterprise. Supervisors must prepare their higher degree researchers for this new world, which reaches far beyond where a thesis-as-cake will take them.

Where thesis supervisors may once have been able to focus purely on research outcomes to support higher degree researcher success, contemporary career paths require more diverse preparation for post-graduation career success. Supervisors need to be aware of the changes happening beneath their feet in the higher education landscape to set up higher degree researchers for research success and to prepare them for the emerging societal impact reality in universities, government, and industry. Conversations and experiences regarding publishing, scholarships, and awards remain important, but supervisors must also consider how best to foster success for future impact generation throughout the higher degree.

Supervision for Societal Impact Ecosystem (SSIE) Framework

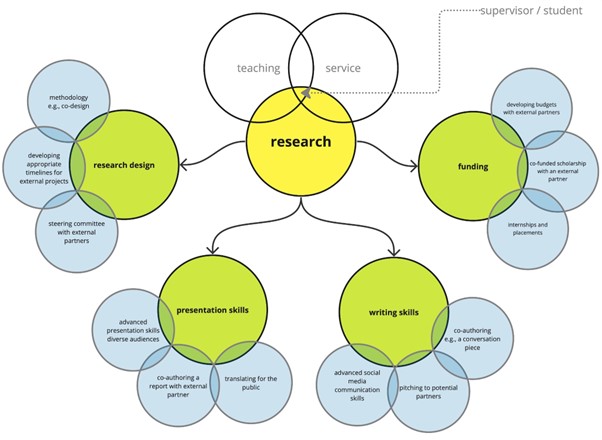

The Supervision for Societal Impact Ecosystem (SSIE) is a practical framework that explores the potential pathway from community engagement to impact within the context of higher degree research preparation. The sections that follow provide background on various dimensions of the framework; we argue that being exposed to societal impact-related thinking and approaches in terms of presentation, writing, research design and funding, are critical to embed an impact mindset and to develop higher degree researchers’ societal impact-related skills.

The framework (see Figure 13.1) is a starting point for supervision, rather than an end point. The diagram is intended to foster discussion and exploration between higher degree researchers and supervisors and can be revisited throughout the program. Practically, it can be adopted as a mapping tool to address higher degree expectations and needs, and to track researchers’ progress across domains.

A holistic approach to research “training”

The thesis artefact (whether in manuscript form, or as a collection of published papers) remains the primary end-product of the higher degree process. It is little wonder, then, that higher degree researchers and supervisors often focus on the conceptual, theoretical, and technical aspects of research, such as methodological design, project planning, and data analysis. These are critical to research success and, typically, involve new areas of investigation and work for higher degree researchers. Yet, some supervisors encourage higher degree researchers to focus primarily (or only) on thesis-related work, while neglecting the broader research ecosystem and its implications for higher degree researchers’ futures. Higher degree preparation must also address future career paths, which may be uncertain or precarious, whether inside universities or beyond. Higher degree researchers must gain experience communicating and working with potential beneficiaries of their research, outside of the academy.

Supervisors can adopt holistic approaches to research training irrespective of higher degree researchers’ anticipated career trajectories, in academia, government, community, or industry. Effective supervision means expanding the conversation scope with higher degree researchers beyond the confines of the thesis (as also discussed in the chapter on “careers” in this volume). A higher degree is not solely about completing a thesis; it encompasses a spectrum of experiences and opportunities for holistic career development. By acknowledging and building on higher degree researchers’ previous experiences, supervisors can create a supportive and inclusive learning environment. This entails considering the whole person by engaging in mentoring conversations that extend into the higher degree researcher’s past (drawing on previous experience), acknowledging their present (current goals and expectations), and projecting into their future (where they want to go, post-graduation, and what skills they need to get there). All stages of this conversation should include discussions of the potential societal impact they wish to generate across their career.

This approach revolves around developing a comprehensive understanding of higher degree researchers’ potential career trajectories and strategically embedding activities throughout the higher degree program to develop a wide complement of skills. For example, higher degree researchers should be exposed to budgeting, ethics, stakeholder engagement, writing and presenting for non-academic audiences, policy development work, pitching to industry funders and philanthropists, and other crucial skills and experiences required to understand and deliver societal impact from research.

The following sections explore various dimensions of the “engagement to impact” continuum and provide possible approaches for supervisors to take in supporting higher degree researchers in skill acquisition and development related to this work.

Modelling an impact mindset from day one

In the first year of the higher degree, supervisors should emphasise the importance of considering potential societal impact of the proposed research during the project scoping phase. Among other considerations, this could include designing needs assessments, exploring ethical considerations, and planning to share research findings with relevant stakeholders. While not all higher degree researchers can design a study with direct involvement of an external partner or anticipate where their research will have an immediate impact, exploring what might be possible within the constraints of the higher degree should be encouraged. Many higher degree researchers may have pre-existing relationships with community organisations, for example, which could become potential sites for data collection and for addressing an organisation’s needs. Other higher degree researchers may need to learn strategies for building connections with potential research partners, which could be pursued after graduation. This is an apt opportunity to discuss the nature of relationship building, including what equitable partnering looks like, as well as the logistics involved in contracting processes, in ethics review, and in co-authoring publications with partners. Collaborating with external partners can amplify the reach and relevance of higher degree researchers’ projects, but it must be done with reciprocity and trust, and appropriate to the higher degree researchers’ individual needs and circumstances.

Supervisors play a vital role in preparing higher degree researchers to understand the potential impact of their research. By exploring different methodologies and emphasising the translation of research findings into practical outcomes, supervisors can empower higher degree researchers to plan for, evaluate, and report the societal relevance of their work. This approach ensures that higher degree researchers view the higher degree as an opportunity to make contributions to their field, as well as to the collective good of society, by planning ahead for impact-related work.

For those higher degree researchers who may not be able to engage with external stakeholders during the degree, conversations can still be had about ethical practices, whether it be around sustainability and waste in medical research, reduction of animal models in biological research, or strategies for engaging with government policymakers. All of these are contemporary issues in higher education related to societal impact.

For those higher degree researchers with ready access to potential partners, stakeholder engagement throughout the research process is crucial for research to have an impact. Supervisors can help higher degree researchers to identify potential partners using stakeholder mapping processes, to communicate appropriately with stakeholders, and to involve partners in co-design and co-production processes.

Supervisors can also explore the potential for industry and community partners to be involved in formal co-supervision of the research. This is done as part of the formal contracting process between the university and the partner organisation and needs to be managed by Principal Supervisors on behalf of their higher degree researchers. Of course, external partners will likely need mentoring and support in the supervision role, which can be provided by both academic supervisors and the university’s graduate research office.

Modelling a holistic approach: What it means to be an academic

The routines and expectations embedded within early levels of education — from K-12 to the undergraduate experience — often require disruption and unsettling. The higher degree is not — at least, it should not be — as highly prescribed as previous educational experiences. Supervisors are not bosses, friends, coaches, or teachers. Supervisors are guides; the higher degree researchers are apprentices. This relationship can be confronting to higher degree researchers who have come to expect rote learning and highly structured processes and outcomes. Supervisors share the breadth of their roles and responsibilities, and discuss local and global socio-political constraints, providing a clearer picture of what the academic experience entails. Engaging for impact necessitates supervisors address several key areas during their conversations and interactions with higher degree researchers, ensuring they are exposed to a range of experiences to shape their understanding. A diversity of experiences also provides opportunities for higher degree researchers to determine what skills they wish to use (or not use) in future.

Sheltering higher degree researchers from service opportunities (such as committee work, for example), may mean the thesis is completed more quickly, but it comes at a cost. Being able to develop a higher degree researcher’s concept of an academic trajectory starts with a conversation about the nature of higher education and the roles and responsibilities contained within it. Sitting on a university-level committee, serving as a peer reviewer for conference presentations, or joining a disciplinary awards committee are experiences that can help higher degree researchers to grow their skills and extend their professional networks. Discussing these experiences with supervisors can support higher degree researchers to critically reflect on their skill profiles and identify areas for further growth. The engagement skills relating to systems thinking, governance structures, committee processes, and even how to challenge senior colleagues and advocate for your needs, can all be learned through service within the academy and the broader discipline. While these skills can be acquired in an academic context, they are not limited to it; such skills are highly valued within, and transferable to, industry, government, non-profit organisations, and other contexts outside of the academy.

The development of impact skills can be fostered across various other dimensions of the higher degree. Most supervisors have teaching, research, and service responsibilities, yet the experience for many higher degree researchers is limited to the research realm. In addition to research and academic service opportunities, supervisors should consider how they can promote engagement for impact through teaching and community-based service activities. Planning for sessional teaching opportunities from the outset of the higher degree helps the higher degree researcher to plan their research time, accordingly, while also helping the academic unit to plan for future workforce needs. Sitting on a non-profit organisation’s working committee can help higher degree researchers gain critical insights into the challenges and benefits faced in the community while providing the non-profit organisation with expert advice and a pathway for broader engagement within the university. Higher degree researchers can also undertake industry placements, service learning, or contribute to campus-based science camps for K-12 schools, to gain relevant experience.

Engaging in conversations about the nature of higher education, global trends in the sector, and political forces shaping research and teaching priorities, are important for researcher development. Some higher degree researchers will move overseas; many will hold a series of different, short-term roles, while they look for permanent work; and others will juggle caring responsibilities alongside higher degree completion and the transition to work. Their thinking must extend beyond the local culture and the immediate future. Supervisors should encourage higher degree researchers to lift their heads up, look around them, and understand what is happening in their departments, schools, faculties, and in their cities, states, countries, and globally. This will help them to see their place in the world and anticipate where they can contribute, in future. Understanding the internal and external forces that shape universities will help researchers in navigating a post-doctoral life.

In the context of societal impact, this conversation may be shaped by sharing relevant contemporary articles on higher education and impact. It may include reviewing granting requirements from various funders or discussing how changes in policies in other countries can put pressure on local institutions to adjust their practices.

A good starting point for discussing higher education is to consider the meaning and intention behind the social contract between universities and society. There is no single answer to this question, but many higher degree researchers have never considered this issue. Why do we do what we do at universities? What is our social responsibility to the environment, people, heritage, or the economy? Given rising dis/misinformation, what role do universities have in fostering expertise and knowledge sharing?

Conversations will likely take different forms for those in applied, professional, theoretical, and creative practice disciplines. Yet this is a core part of building an understanding of the discipline and how it relates to others, of the broader sector, and of emerging pressures and expectations that shape how each discipline evolves. As much societal impact work embeds transdisciplinary thinking and experiences (i.e., where interdisciplinary research embeds stakeholder interaction and benefit), extending higher degree researchers’ understandings of what academic work looks like within this context is paramount for future research and impact work.

Communicating for societal impact

In any job, communication skills are vitally important. Historically, academic programs prepared higher degree researchers to communicate with people who think and behave in similar ways to them — other academics. If societal impact is the destination, engagement outside of academe must be part of the journey. Being able to communicate with a wide range of audiences, in various sectors, is an increasingly valuable skill. This takes many forms, including science communication, knowledge mobilisation, mass media engagement, social media postings, public presentations, funding pitches, policy briefings, translating research for practice change, and much more. The following sections address writing and presenting skills, as these are the most common (and most overlooked) strategies for engaging beyond academe. The communication continuum extends beyond these areas, and supervisors would do well to consider how interpersonal skills are being fostered, as well.

Writing skills

Writing the thesis allows higher degree researchers to hone their academic voices and learn disciplinary expectations for scholarly publishing. Higher degree researchers absorb what they see modelled in journal articles, conference papers, book manuscripts, and other sources of academic writing to inform the thesis style. Through an acculturation process, higher degree researchers begin to perform in ways that are consistent with the established norms of their disciplines. Increasingly, higher degree researchers are engaging in interdisciplinary research and are publishing articles and book chapters alongside (or as part of) the thesis itself.

Supervisors can provide advice on solo publishing, but they can also serve as co-authors on higher degree researchers’ publications; in this way, supervisors can model and support publishing practices that higher degree researchers need to pursue academic careers and to work in industry-based research contexts. Building a track record of publications is also important for scholarship and small grant applications, and for future career development. Supervisors should take active roles in supporting their higher degree researchers in these endeavours.

Writing for academic peers is a critical component of the higher degree experience; however, developing the ability to write for various audiences, beyond academe, is crucial for the types of engagement work that can lead to societal impact. Unfortunately, this type of writing often receives minimal attention during higher degree studies.

Encouraging higher degree researchers to develop a translational writing voice can take many forms. It starts with supervisors emphasising the value of writing for non-academic audiences and modelling what this style of writing entails. This can include sharing articles in The Conversation, blog posts, newspaper articles, artwork, or stories authored by academics from various disciplines. By discussing what elements make for quality pieces (e.g., explaining terms, accounting for jargon, reducing complexity, using metaphors), supervisors can normalise the practices of crafting research outcomes for generalist readers and of establishing a public voice alongside one’s academic reputation. Being able to synthesise complexity for various audiences is critically important for getting research outcomes in front of policymakers, community groups, and corporate decision-makers, among other types of non-academic stakeholders.

While academic publications take countless hours, producing public-facing news articles, briefing notes, executive summaries, and trade publication articles based on research outcomes takes much less time. This presents an excellent opportunity for supervisors to co-author these types of publications with higher degree researchers.

When supervising higher degree researchers in science or other disciplines where thesis-by-publication is the norm, co-authoring a piece for The Conversation can extend the reach of a newly published work.[1] For higher degree researchers in humanities or social sciences disciplines completing manuscript-style theses, supervisors and higher degree researchers can pitch an article to The Conversation to connect research outcomes to a current event or popular culture.[2] The university’s media team can provide training and support for writing for this venue, as well as post-publication profiling of the work.

Higher degree researchers should be encouraged to write for and with non-academic audiences, co-authoring articles and reports that are accessible and relevant to a broad readership. It is important to stress that all outputs, including media coverage, policy reports, popular publishing, and other non-academic and community engagement pieces should be listed on higher degree researchers’ CVs. The research degree is a balancing act, so the natural caveat is that some public-facing writing is valuable, but too much may be counterproductive and delay degree completion.

Presenting skills

Higher degree researchers come from varied backgrounds, have different life experiences, and are different ages. However, for many, their first presentations to peers will be during their research degrees. For higher degree researchers who have progressed through undergraduate, honours and/or masters-level degrees, and onto the PhD, the knowledge of how to present, and what makes a good presentation, may be limited. As with finding their writing “voice,” higher degree researchers will replicate what they see in classrooms, seminars, and academic conferences.

Unfortunately, even the most compelling academic presentations may not translate well (or easily) for a public or practitioner audience. It can take years for academics to hone their presentation skills (including the design of excellent slides) even within their own disciplines. Presenting to interdisciplinary teams requires translation of disciplinary content across academic contexts, where even the style and format vary. In the creative disciplines, for example, interactive exhibitions are the norm; in the humanities, it is common practice for researchers to write full papers, which they read to the audience. In the social sciences, PowerPoint slides are the norm, where academics “speak to” (rather than read) the content displayed. And, in the sciences, academic poster presentations provide for interactive engagement with the audience. All these forms of presentation are demonstrated to, and expected of, higher degree researchers by their supervisors and other scholars in their disciplines.

A person who cannot present well to academics will likely not present well to government, community, and industry stakeholders. However, the risks can often be greater for the individual, and for the reputation of the institution, in these contexts. Showing poor verbal communication skills, with slides packed with too much content, or based on a paper that has not been translated well for the specific audience, can have dramatic negative consequences in front of politicians and the media. Making a pitch for funding from an industry or community group that does not speak to that audience’s needs, or using terminology they cannot understand, is almost certainly doomed to fail.

Most universities have media training programs for researchers that are available to higher degree researchers. Some universities have generated training modules that offer guidance, as well. The Three Minute Thesis (3MT) competition is one opportunity for higher degree researcher to consider how to present their research in a digestible and accessible format. And, many countries host events like Social Sciences Week,[3] Pint of Science, or Nerd Nite, which welcome speakers from across disciplines. Encouraging higher degree researchers to engage in these activities, or training exercises like Toastmasters, will pay dividends in unexpected ways, including enhancing professional networks and gaining media exposure.

Putting it into Practice — Holistic “Supervising for Impact” Discussion Prompts

A holistic approach should be used (and will evolve) throughout the research higher degree journey.

Step one: prepare for the conversation. Explain why an emerging dialogue around engagement and societal impact is important in terms of personal motivation, development, and career trajectory, and to get the most out of the higher degree by research experience.

Step two: make the time. These conversations can be challenging and sprawling. Adding them to the end of a conversation about thesis revisions may not be ideal, as the higher degree researcher will be focused on thesis work. Set aside dedicated time for these conversations.

Step three: encourage thinking aloud. Take notes and reflect on what the higher degree researcher has shared. Use open ended questions (including asking “why?”) and paraphrase to foster dialogue. Play devil’s advocate to foster critical reflection about impact-related work.

Step four: ask questions. Prompts could include: What kind of career will you pursue? Are you considering careers beyond academe? How can your research make a positive change in the world? What excites you about the potential contribution your research could make to society? Do you have experience communicating with the public? What kinds of skills do you need to engage with industry, government, or community? How can you make contacts outside academia to share research results?

Step five: follow-up. Continue the conversation and adjust supervisory practices to align with each person’s higher degree goals. Higher degree researchers will need different supports and opportunities to develop impact-related skills.

Building your academic profile: Be Googleable

Many institutions feature higher degree researchers on their websites, often as members of labs or research centres, and in relation to funded projects and scholarships. Unfortunately, the small amount of content that is typically profiled, and the lack of control by individuals to edit university-based pages quickly and easily, means higher degree researchers struggle to extend their reach.

Supervisors should develop their own publicly-facing websites to profile their work, and they should encourage their higher degree researchers to do the same. Researchers change roles and institutions and they need to have robust, stable websites that can follow them throughout their career. Using WordPress or other tools to create a professional website is a critical first step for supervisors and higher degree researchers. Personalised domain names and hosting are relatively inexpensive; and, websites can be as simple as an online CV and a short bio, or they can include listings of projects, partners, and multimedia presentations.[4] In addition to scholarly achievements, the personal website can communicate capabilities (e.g., “I’m adept at mixed-methods, co-design, and knowledge translation”) and values (e.g., “my focus is on making life better for young mothers”), can showcase external engagement (e.g., reports, blog entries, podcasts), and provide evidence of societal impact (e.g., “my framework has been adopted in 31 care facilities across the country”).

The value of establishing a website early in the research degree process is that search engine optimisation (SEO) can take years to promote new sites to the front page of search results in Google and other search engines. When a higher degree researcher first creates their website, it may not be easily findable; but, by the time they are on the job market, employers and potential partners will find them quickly. Prospective higher degree applicants also use Google to locate potential supervisors, and they want to see project details for higher degree researchers who have been supervised previously. Robust websites can go a long way to attracting potential partners, funders, media, and individuals who want to read and cite researchers’ work. Professional websites can also help event organisers to quickly locate headshots, social media links, and biographies for inclusion in event programs.

In addition to creating professional websites, higher degree researchers should create profiles on international academic sites (such as Google Scholar) and maintain a current ORCID. Researchers should devote time during their higher degrees to building and maintaining these profiles, as well as growing their scholarly reputation through LinkedIn, X (formerly Twitter), Threads, BlueSky, and other social networking spaces. Higher degree researchers should also include these details on business cards and publications, to foster outreach through various channels.

Conclusion

Supervising higher degree researchers to prepare them for societal impact work requires a holistic approach extending far beyond the traditional boundaries of thesis preparation. By emphasising the importance of the entire, end-to-end research process, including engagement with non-academic stakeholders and planning for potential societal impact, supervisors can empower higher degree researchers to make meaningful contributions to society. It is essential for supervisors to think beyond their institutional presence, to guide higher degree researchers in building both their academic and public-facing profiles, and to encourage engagement with industry, community, and government. By adopting these strategies, supervisors can shape a new generation of researchers who prioritise societal impact and contribute to a better future through strategic engagement.

- Here is an example for a thesis publication: Keith, R., Hochuli, D., Martin, J., & Given, L.M. (2021). 1 in 2 primary-aged kids have strong connections to nature, but this drops off in teenage years. Here’s how to reverse the trend. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/1-in-2-primary-aged-kids-have-strong-connections-to-nature-but-this-drops-off-in-teenage-years-heres-how-to-reverse-the-trend-165660 This piece was co-authored by the full supervisory team (Hochuli, Given, and Martin) in support of their PhD student (Keith). The PhD research involved an external organisation, with Martin co-supervising as an industry partner. This piece has been read more than 11,000 times and garnered significant media attention. ↵

- Here is an example linked to a major popular culture event: Forcier, E., & Given, L.M.. (2019). After 8 years of memes, videos and role playing, what now for Game of Thrones’ multimedia fans. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/after-8-years-of-memes-videos-and-role-playing-what-now-for-game-of-thrones-multimedia-fans-117254 This piece was co-authored by the student (Forcier) and principal supervisor (Given), following the supervisor’s recommendation to pitch an article ahead of the release of the final episode of Game of Thrones. This piece has been read almost 15,000 times and was featured in international media. ↵

- For example, the Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia hosts an annual Social Sciences Week event https://socialsciencesweek.org.au/ ↵

- See https://www.wadekelly.com/ and https://lisagiven.com/ for inspiration. ↵